Visitors to the Republic of Cyprus who expect an unspoiled retreat may be disappointed when they discover the extent of the commercial development which has transformed the coastline in recent years. Although this had already begun in the 1970s, it has escalated after the division of the island in 1974. Unregulated building occurred as a result of an urgent need to employ the thousands of refugees from the north and few regulations protecting the environment.

“We were striving for confidence and stability. We got it through economic development, but future generations won’t see it that way,” explained Andreas Demetropoulos. A marine biologist and oceanographer who studied in North Wales, he is the Director of the Department of Fisheries of the Ministry of Agriculture and the President of the Cyprus Wildlife Society.

Regulations went into effect in the 1980s, and in 1989 the government also imposed a building moratorium on coastal tourist development and stricter guidelines regulating other construction.

A Greenpeace group attracted worldwide attention when it demonstrated on Cyprus to discourage developers from moving in bulldozers and developing tracts of the unspoiled Akamas Peninsula north of Paphos. Pressure to allow construction in Akamas has been placed on the government by the developers who have bought up choice tracts of coastal property and some of the inhabitants who feel they have been cheated out of a certain amount of the prosperity that swept the rest of the island.

“This is only natural,” says Demetropoulos. “One of the things that must be included in a conservation plan is some type of compensation for the people whose land will be incorporated into the state park.”

The Cyprus Wildlife Society has been instrumental in forging measures designed to protect the natural resources. It was successful in preventing construction of a paved road which would have cut across some of the Akamas areas in which the green and loggerhead turtles nest. As a result of man’s encroachment on their territory, the turtle population has declined to the extent it has been declared an endangered species by the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The Mediterranean Monk Seal, now nearing extinction, along with dolphins, is protected species as well.

Much of Demetropoulos’ work since 1976 has focused on the Akamas peninsula area. His tireless campaigning for the protection of beaches inhabited by the turtles and for the creation of a National Park in Akamas has won him the prestigious ‘Global 500’ Award from the United Nations Environment Campaign.

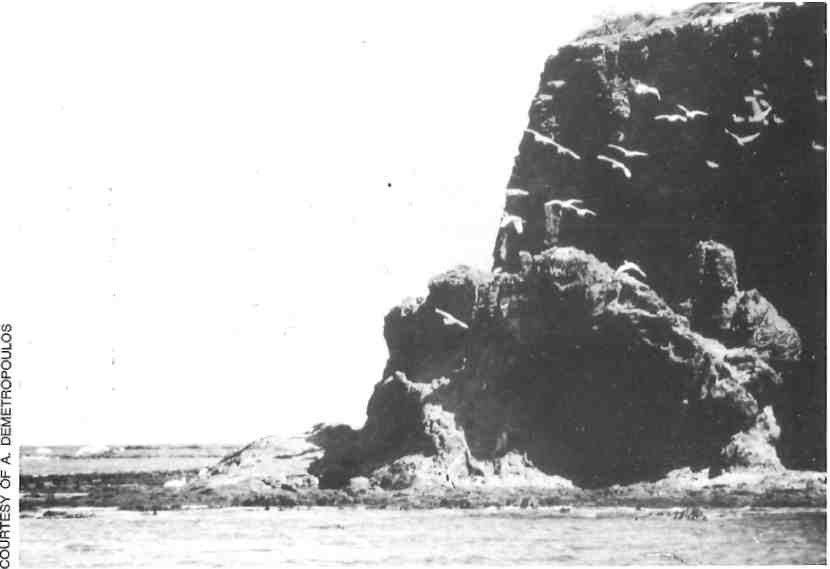

A national park is already being established in Cape Greco, a rocky coastline in the Larnaca district, in the eastern part of the island. Demetropoulos is optimistic that another national park will be established soon in the rugged Akamas area, the most unspoiled area remaining on Cyprus. A team from the World Bank is expected to arrive on the island to study the Akamas peninsula over a nine-month period and to make recommendations for the management of a park.

The EC has provided funds via its MEDSPA program for turtle conservation. Demetropoulos was involved in the early stages of the turtle conservation project in 1976-77 when a thorough study of the turtle breeding area was undertaken. It showed that the Green turtle breeds almost exclusively on the desolate surf-swept beaches of Lara on the west coast of the island, north of Paphos. Loggerhead turtles breed on most beaches that provide some privacy at night.

Turtles are an ancient group of reptiles that have reversed their evolution and returned to the sea. Although they have adapted well and are excellent swimmers that can stay underwater for long periods, they still have to breath air and still come up on land to lay their eggs in the area in which they are born. This takes place every two years from the beginning of June until the middle of August. During the breeding season they lay a clutch of about 100 eggs in a hole dug in the sand at night.

Regulations were formulated for the protection of the turtles and are now being enforced by a patrol. It is forbidden to place sun beds, umbrellas, caravans or tents on the beach or to stay overnight. The Lara Turtle Project is the first and is still the only one of its kind in the Mediterranean. Through the project, staffed mostly by volunteers, about 4000 hatchlings are released every year. This is about 3-4 times the number that would normally reach the sea if the nests were not protected. Best results have been obtained from reburying the eggs rather than incubating them in polystyrene boxes.

An experiment is now taking place with about 100 more turtles ranging from one to ten years old who are being kept in special tanks and sea cages and released at various ages when they are too old to be eaten by most predators. They are tagged so that when they come back to the beaches at which they were raised they can be identified.

Demetropoulos stresses, “We have had so much publicity about the Lara Beach area that many people have been attracted there, complicating the work of the volunteers.” He is keen to promote exploration of other sections of the island, such as the Troodos massif, Paphos forest and Cape Greco that also offer interesting nature trails with varied vegetation and wildlife.

The foothills that fringe much of the Troodos mountains rise to about 750 meters and, though somewhat varied in their geological makeup, have an interesting and diverse vegetation. Bee orchids and other types abound in this area in which large stretches of untilled land alternate with the remnants of older forests. The Pistachia terebinthus, with red foliage in the spring and autumn, is common here, as well as wild or cultivated carob trees. Carob beans are believed to be the locusts with honey eaten by Saint John in the wilderness. They have been a staple crop, accounting for much of the exports of Cyprus in the early 1800s.

As the Troodos range begins, the vegetation changes. White rock-rose and fragrant wild lavender grow here. On the higher slopes, many endemic and rare plants thrive including hellebor and spectacular red peonies. Rare orchids are scattered over the banks of streams.

From clear fossil evidence, it can be assumed that Cyprus was at one time colonized by hippopotamus and elephants, but probably because of the absence of predators these evolved into dwarf species. When man first colo-nized the island, 8-10,000 years ago, these animals disappeared and the first inhabitants brought species of deer, wild goat, and the reclusive wild sheep known as moufflon. The indigenous mammals include the fox, hedgehog, hare, shrew and several bat species including the Egyptian Fruit Bat.

The moufflon was on the brink of extinction at the turn of the century, its population estimated at a few dozen. It was saved by introducing strict protective measures and has rebounded, with an estimated 2000 living in the Paphos and Troodos forests.

“They have come back so strong, they have almost become pests in some ways,” says Demetropoulos. “We have to deal with some destruction they cause such as nibbling away at the vineyards grown to make wine.”

Nature lovers in the Troodos will be enchanted by the sites of the Chrysorroyiatissa Monastery, and the forestry station of Stavros Tis Psokas, both accessible by a four-wheel drive vehicle with a full tank of gas. The last eight kilometers of road leading to it is on a narrow dirt road, one almost impossible to follow in bad weather. The extensive forest, mainly of stately Golden Oak, about 50,000 Cedar brevifolia and Aleppo Pine, lends the landscape a sense of grandeur. The area is rich in birds.

Ο Stavros Tis Psokas (meaning the Cross of the Measles because a spring here was supposed to cure the disease), has a canteen and rest house, its cozy suites with kitchen and fireplace can be reserved for stays of up to three days. Some of the moufflon are kept in an enclosure next to the rangers station. Early risers with patience may spot them in clearings in the forest.

Of about 18,000 species and varieties of plants that grow on the island, about 120 are endemic or only grown in Cyprus. The island’s tremendously diverse flora attracts a rich variety of butterflies, which are dependent on plants for food for their larvae. About 55 species can be found in Cyprus, an astounding figure when one realizes the same figure applies to all of the British Isles. The butterflies fly in several broods, especially noticeable in the plains and lower foothills. The best time for butterfly watching is an hour or so after sunrise when these delicate creatures warm themselves in the sun before they take to the air.

Among the endemic species are the Paphos Blue, a species in which the male is a stunning electric blue on its upper wings while the female is a drab brown. It is common in the Troodos fφ thills and Akamas. The Yellow Swallowtail, distinguished by striking black patterns, is found in the lower Troodos where its caterpillars nibble mainly on fennel plants. The rare and resplendent marble-patterned Two-Tailed Pasha, can be sighted high in the Akamas and near Platres in Troodos.

Cyprus is a significant stopover point for birds, mainly in the north to south migrations in spring and autumn. Many species are regular migrants, including about 10,000 distinctive Coral Flamingoes who pause at the salt lakes of Larnaca and the Akrotiri peninsula in November or December on their trip south, providing great shots for photographers. Other migrant waterbirds include Coots, Mallards, Lapwing and Ringed Plover. Spring migrants include the Glossy Ibis and several species of Egrets, Herons and many waders.

Common feathered residents include the Crested Lark, Wood Pidgeon, Kestral and the majestic Barn Owl, a shrill-voiced bird of prey. Bonelli’s Eagle is the most common predatory species and about 20 pairs of fierce-looking Griffon Vultures breed on the island. Other endemics include the Cyprus Warbler, the Coal Tit and the tiny insectivorous Scops Owl, a frequent visitor to olive groves and gardens.

Unexpectedly environmentalists say their efforts have been boosted by the Gulf War, during which time the island’s tourism waned, leading to an awareness of the fragility of a tourism-based economy. Economists, government planners and environmentalists have been expressing concern that the emphasis on tourism had gone out of control and the quality had been downgraded. Adrian Akers-Douglas, a keen environmentalist and moving force of the Friends of the Earth described the decrease in tourism as ‘the silver lining’ to the Gulf War. “Everybody realized the bubble could burst,” said Akers-Douglas. “When it did, low-level package tours were the first to collapse.”

This setback provided a jolt which awakened many Cypriots to the need for diversification of the economy, with an emphasis on more stable facets leading to a self-sufficient infrastructure. In contrast to the previous ‘Sea, Sun And Fun’ only advertising of the past, the Cyprus Tourist Organization (CTO) and tour organizers now emphasize the traditional aspects of Cyprus and the many idyllic retreats off the beaten track where nature lovers will find much to explore and appreciate.

The CTO issues a booklet with descriptions of the well-marked paths it has established in the Troodos Range, Paphos Forest and other areas. It is available at the CTO office in the Laiki Yitonia area of Nicosia , tel. 02/444-264, and at branches in the airports and towns. Experienced hikers caution walkers to be equipped with a whistle, compass, water supply and jacket or pullover. Do not walk alone after heavy rainfalls or after dark. Always tell someone at your lodging, your itinerary and when you are expecting to return. Many areas of Cyprus are isolated and if you are lost or injured it could be some days before you are found if no one else knows of your whereabouts. Exalt Tours, which can be contacted at Iris Travel, 10 Gladstone, Paphos, tel. 06/237585, offers nature hikes and treks through remote areas such as the Diarrizos river-bed with a knowledgeable guide.

The government has encouraged small scale tourism in accommodations operated by villagers in outlying Akamas communities. Environmentalists have developed a package known as the Laona Project. The environmental protection group known as Friends of the Earth, assisted by private and EC funds, renovate some houses and provide funds for others to restore their own small units. These can accommodate guests who want to stay in a genuine Cypriot environment unmarred by heavy traffic or nearby discos and bars.

Samantha Stenzel is project editor and a contributor to the Nelles Guide Cyprus. Andreas Demetropoulos contributed the “Flora and Fauna” section and detailed nature walks in the guide.