Sketches by Alina Gabrielatos

The ferry link between Tasucu on the south coast of Turkey and Girne (Kyrenia) on the north coast of Cyprus seems to encapsulate the plight of the occupied northern part of the island. Nominally a four-hour crossing of the Karamanian Straits, it often takes twice as long owing to decrepit boats limping along on one engine. The craft tend to be no-longer competitive tubs dumped from elsewhere. Among them are currently a veteran of the Cesme-Chios route and a donation from the ex-Soviet Union. Those in the know take the more reliable and comfortable Mersin-Famagusta line. In the cattle-shed-like customs facilities at either end, Anatolian Turks are treated like animals, Cypriots marginally better, and the rare foreigners as honored guests – telling distinctions.

Recognized internationally by no country but Turkey, its creator and main sponsor, the ‘Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus’ possesses at first glance a Ruritanian charm, with nearly antique Hillmans and Vauxhalls tooling about, policemen in grey summer twill, and traffic signals that still have a colonial ‘STOP’ stencil over the red light. But there are a few ugly twists.

The ubiquitousness of the Turkish army is off-putting. While there are fewer no-go areas than there were five years ago, barbed-wired camps abound, and some 25,000 mainland conscripts, on-duty or off, lend a barracks-like air to Kyrenia and Nicosia in particular. Although nearly 20,000 Greek Cypriots at first chose to stay in the Karpas Peninsula after 1974, and perhaps a thousand Maronite Christians in the Kormakiti area, systematic harassment by the authorities has reduced those numbers to roughly 600 and 200 respectively.

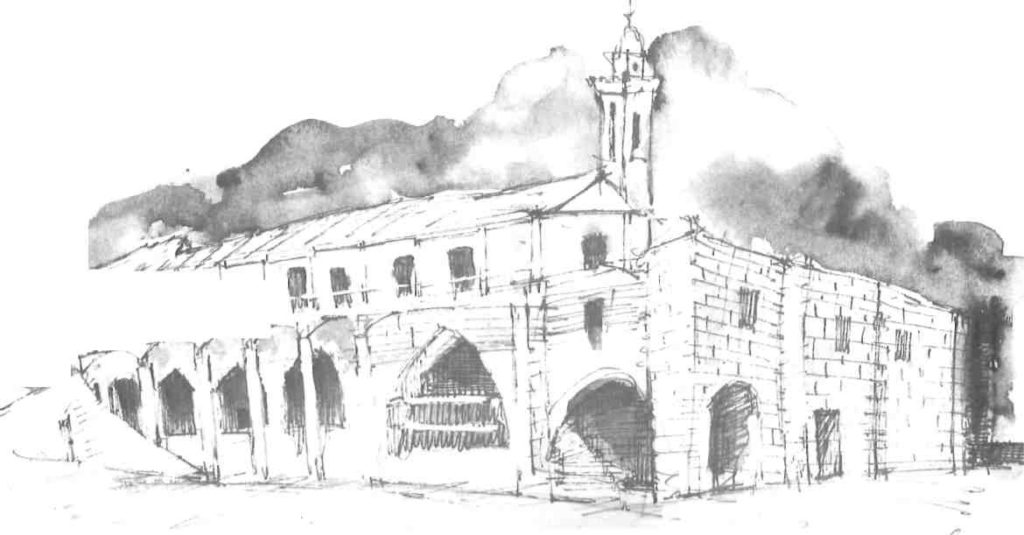

The internationally publicized desecration of Greek (and British) churches and graveyards is unfortunately true, though the authorities in the South occasionally overstate their case. The Byzantine monastery of Ahiropiitos near Kyrenia, for instance, had been virtually deconsecrated and occupied by the Cypriot national guard before 1974, as had the monastery of Chrysostomos near Nicosia – both now used by the occupying Turkish army. Greek Cypriots are in the main careful to attribute, at least in print, the blame for this where it belongs: on the invading mainland army, since for many of the Turkish Cypriots, Orthodox shrines, catacombs and so on are also felt to be sacred.

some stubble. He was sweet-tempered and God-fearing

Generally there is a feeling of grass growing up through cracks; often this is literally true. The public infrastructure is starved of funds, since all international, post-1974 aid is shunted to the South. Less and less support is forthcoming now from Turkey which has lately had other priorities and troubles. Things appear to be maintained, but no more. Improved and enlarged roads are confined to a single strip along ‘Hotel Row’ west of Kyrenia, and the vital Nicosia-Famagusta highway. The Turkish army had in 1974 bitten off rather more than the 120,000 Turkish Cypriots themselves could chew; much of the North is under-utilized, the rural villages half-empty, citrus orchards two kilometres from Kyrenia dying of neglect despite abundant water to irrigate them. The best lands and houses were allotted to locals, while the leftovers -poorer, isolated spots with land fit mainly for grazing – have tended to be filled with settlers brought over from Anatolia.

The ‘settlers issue’ epitomizes the chronic tension between native Turkisu Cypriots and the mainland, with the former (rightly) considering themselves to have a higher standard of living and education. In Turkey a long-standing, patronizing quip characterizes Anatolia as anavatan (mother homeland) and North Cyprus as yavru vatan (baby homeland). The islanders return the compliment by dubbing all mainlanders karasakal- ‘black beard’ (perhaps after the facial hair of the more religious settlers), and a pun or corruption of karasal, continental. Turkey has long treated the island as a Botany Bay kind of off-loading colony for a surplus urban underclass, landless peasants, low-grade criminals and mental cases, along with campaign veterans’ families, until the locals had had enough and began to send them packing. Since no accurate census has been conducted by anyone on the island since 1960, estimating immigrant numbers is an inexact science, with guesses ranging from 30,000 to 80,000. Their fate is a big sticking point in any peace treaty.

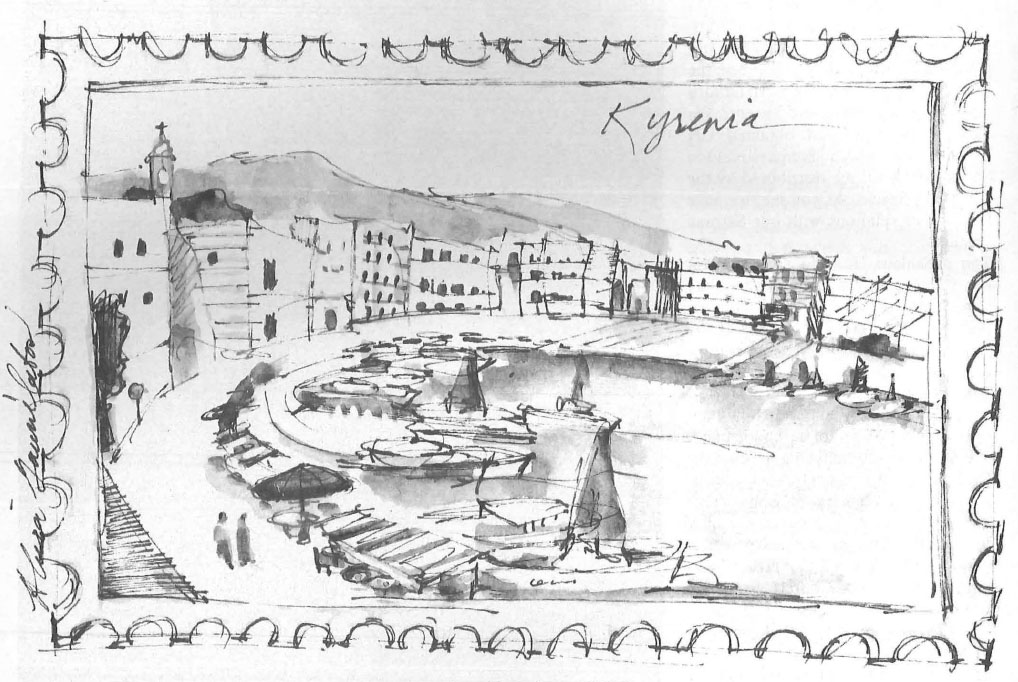

On my first stroll around Kyrenia’s postcard-perfect old harbor, “Zorba’s Syrtaki” was being repeated every 20 minutes on one of those endless loop-tapes beloved of package resorts. It seemed a grisly bad joke under the circumstances, though I later got a hint that a taste for Greek music was not totally unheard of among the islanders. The esplanade was almost empty at noon, and again at 3 pm, in late June.

Partly because of the international stigma attached to the North – for instance, all flights must touch down first in Turkey owing to the IATA boycott of Ercan airport – tourism is scarcely more developed than in 1974. In many ways it is a refreshing change, carried on almost exclusively in hotels abandoned by Greek owners. The northern government from right after the invasion administered these through a tourism development corporation, leasing them out as concessions to interested parties.

Not surprisingly, nepotism is rife and standards of service usually low, with the pre-1974 decor in many cases only replaced in the late 1980s. The bare handful of new, privately-owned and -run resorts are far better.One of the few favors is done for the North by shady tycoon Asil Nadir, before he went spectaculaly broke in the autumn of 1991, was to demonstrate world-standard hotel management on private property with a well-trained staff.

A special category of the tourism development leases is the beautiful hill village of Karmi, where almost all properties have been let since 1982 to foreigners on 25-year leases. Only two exceptions were made for locals, both war heroes and one married to a foreigner. It is thus a bit of an ingrown and bitchy ex-pat scene with recently nothing better to do than to count heads to see whether British or Germans predominated. (It was a dead heat.) The tenants are generally strong supporters of the northern government, and consider that their predecessors got their just desserts. Karmi was an EOKA-B stronghold, and after years of heavy rains the whitewash leaches out revealing old ‘Enosis’ slogans on the walls.

north’s most celebrated tourist attractions.

As everywhere else, the possibility of a settlement was a hot topic in the village’s two pubs. Some were elated at the possibility of longer-term leases, and the opportunity to go for trips in the South. Others feared the steamroller of mass tourism (the backwater quality of the North was a big factor in their coming here) and the arrival, one fine morning, of irate Greek owners demanding their homes back.

I sounded out two real estate agents at the chances of this: “They won’t come back. They’ll be paid compensation for the property they lost. End of story.” Who would provide the money? “The US, funnelled through Turkey.” Considering the fluidity of the situation, prices were high – nearly the same as in the South – and credit unavailable. The single ‘clean’ property I could find, with a Turkish title dating back 50 years, had just been sold.

Abandoned Greek houses or businesses were allotted on a point system to the Turkish refugees who came from the South. One was assigned points for both commercial and residential property according to the value of such property left behind. The scheme was, naturally, prone to abuse. Points lacking or extra ones could easily be bought and sold. Many homes still bear the single-letter, double-digit ‘inventory control’ code assigned by the Northern regime. Fiddling with titles is a popular pastime. Setting aside the rare colonial Turkish titles and the relatively secure tourism corporation leases, there are post-1974 titles given to Turkish Cypriots for Greek homes occupied, and very shaky use-and-occupancy agreements granted to mainland settlers, who often fob them off unscrupulously as genuine titles.

The ruins are not the dead zone but the result of an EOKA rampage. They are preserved as a memorial, shown to school kids to keep hate alive.

One of the estate agent assistants, Ziya, invited me for a drink at his house. Conversation inevitably drifted to the possibility of a settlement. “There will be one this year,” he thought, “because the UN is tired of paying for the peacekeeping forces.” What would happen to the North’s regime and currency? “In a federal administration there would be one Finance Minister and Cypriot pounds. The Turkish lira will be a foreign currency like any other.” The settlers? “They will go.” And what of territorial concessions? “The Greeks will go back to Varosha, since no one is living there anyway, and up to the old Famagusta-Nicosia road. And take part of the Morfou orchards.” Would they have the option to return to the Turkish zone? His face darkened momentarily. “We will never live beside them again.” The three Byzantine/crusader castles which stud the mountain range separating Kyrenia from Nicosia are its most celebrated tourist attractions. As methods of warfare changed, the Venetians abandoned them in the early 16th century, but beleaguered Turkish Cypriots found a new application for at least one of them after 1964. At the Castle of Saint Hilarion they fortified an enclave that cut the main Kyrenia-Nicosia road. From the easterly bastion of the castle itself they could stare across at their mortal enemies in Karmi. Access to Buffavento is today mostly along the road built by Greek Cypriots as an alternate route over the mountains, bypassing the Turkish enclave.

The only way around the hills on more or less level ground lies far to the west and, of course, this road is heavily fortified by the Turks. In the same area, still further west, is the homeland of the Cypriot Maronites or Katholikoi as they call themselves. The most relatively flourishing of four villages is Kormakiti, but even here the population is down to 150, mostly old inhabitants. Seven children keep the school open and the nunnery has two nuns, but mass is celebrated daily though the houses are in poor repair. The Maronites migrated from Lebanon as archers during the Lusignan dynasty. They speak Greek and Syriac, and are overwhelmingly friendly to visitors even by Cypriot standards, despite their obvious straits. It was the familiar story of lands expropriated without compensation by the Turkish army and demeaning bureaucratic harassments.

Despite this they bore no animosity towards the island Turks, ascribed all manner of mistakes to the former Greek administration, and thought it better that the two main island communities live apart. They themselves are given five-day passes to visit the South, and their mobility makes them useful go-betweens. Foreigners buying northern real estate sometimes acquire Greek title deeds (illegally) in this manner. Now the Maronites mostly just hang on, hoping to see an improvement in their own lot when finally a treaty is signed. Otherwise they will continue to emigrate to the South or beyond, inter-marrying with Italians for the most part.

After drinks in one home, followed by a meal at another, I was directed to the central kafeneion. Inside, Beirut football pennants hung next to portraits of various Maronite patriarchs. The phone booth was empty, its pre-1974 apparatus ripped out by the roots and never replaced. A man in a tractor, balancing his coffee on his mudguard, hailed me. “We have no phone, us and the folks on the moon.” The nearest one was eight kilometers away, at Myrtou. What if they needed a doctor? “We put them in a car and drive them to the clinic there. If they die on the way, so much the better for them.”

A friend in Turkey had given me the name and address, in Nicosia, of the husband of her best friend at Istanbul University. I made him my first stop on arriving in the north sector of the capital. Physically, Erol seemed a capsule summary of every invader or settler who ever stopped off on the island; but the whole was more than the sum of

Turkish, Greek, Arabic and who knows what other parts. A big physique was made even bigger by his open-heartedness, earthiness and volcanic energy. A glance took in an insurance agency and travel agency on two floors of the same building. He had fingers in other pies as well, as I would find later. Business was business and he saw to my travel problems first. We arranged to meet for supper that night.

I am amazed by the report of another intermarriage between Turk and Greek. How many more are there

in Cyprus, perhaps hiding the fact?

Compared to the southern sector, the north part of Nicosia is asleep, a village with one-quarter the total population. There are almost no inter-national-standard tourist facilities since few foreigners stay the night. Wander into the back streets and you are a celebrity, but stray too far off, as I did to pee on a bush by the Green Line, and the Turkish army may shadow you – as they did me, muttering “He’s got a camera in that bag.”

One should keep a respectful distance from the dead zone on this side. Any sort of urban renewal is an unaffordable luxury, other than a part of the bazaar for pedestrians (cheap Levis and metal-shops predominating). Principal sights, as at Famagusta, are a handful of Lusignan/Venetian churches converted into mosques, a unique marriage of minarets and Gothic.

One folk museum is housed in a former dervish tekke. The mystic orders, as in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, persisted here long after their proscription in Anatolian Turkey, and still function, as it turned out. In the other, the restored mansion of a grandee, the ticket-seller was entertaining a guest. An exchange of a dozen words with him was enough to determine that Turkish was not his first language. They were, in fact, Kurds from the most grindingly poor districts of Turkey, Mus and Agri.

What did they think of Cyprus? “We like it, a tranquil place.” Like everyone else, they were peace-settlement-conscious. And if there was one?

“We’ll be thrown out,” said the ticket man. “Eighteen years here and no right to remain. Here on short-term work permits.” And if there wasn’t? “War again.” War: in one fast-photo shop is a ready-frame, stick-your-mug in the middle, intended for mainland conscripts. Airplanes, parachutes, artillery pieces swirl around the blank spot, with overhead the legend ‘War for Peace’. The 1974 intervention is universally proclaimed the Peace Action, a product of Orwell’s Ministry if there ever was one.

I am late for supper with Erol, arranged at one of the few fishing villages in the North: Guzelyali, or Vavi-las in former times. There are others at the table so we can’t talk much, but it takes just five minutes to establish that Erol is Dimitris’ second cousin, a man I’d met in the South. “We are related through my grandmother – and she married the village Orthodox priest!”

He is absolutely bowled over that I had met his cousin by chance; I am amazed at another relatively recent report of intermarriage. It was obviously more common than credited. If I had met the offspring of two in a few short weeks, how many more are there in Cyprus, perhaps hiding the fact? I asked if he had seen Dimitris, who was about his age, since 1974. “Many times. I often go to the Greek side. The nightlife is better. I have many friends there. All you need is a contact in a car with southern number plates, waiting for you on Dekelia British Sovereign Base.”

I wanted to hear more but Erol had to go meet a Saturday midnight flight -not, he assured me a foray Over There’. After he left, a bright girl of about 12 in the group spoke up in English. “You’ve been in the South: I want to ask you something. What do the Greeks want? Our teacher says if they come back they’ll still want to kill us all!” This last, with a shrill note of alarm. As patiently as I could I explained: “I think they’ve had enough of EOKA and just want to go home.”

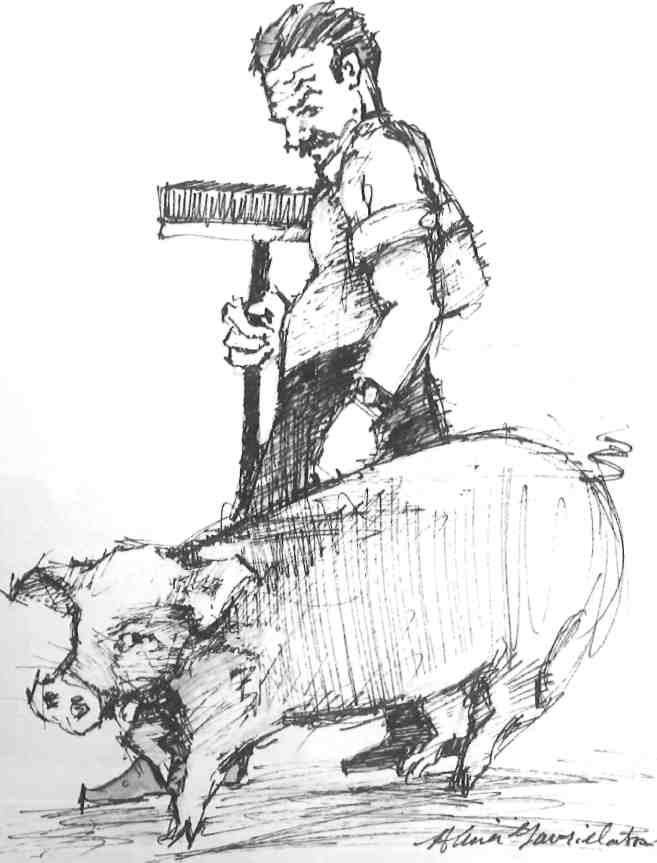

The Greeks of the Karpas Peninsula had tried to stay ‘home’. The monastery of Aghios Andreas near the tip, once among the wealthiest on the island, is a pathetic ghost of its former self. The northern government, perhaps to exhibit its ‘tolerance’, sign-posts it in yellow as a tourist attraction, but runs it as a zoo. Indeed the five remaining Greek caretakers, too dispirited (or closely watched by a Turkish policeman) to talk much to visitors, keep an enormous sow as a pet, presumably to annoy the Muslims. One is silently shown the 19th-century church, and, beneath it, the much older chapel containing the miraculous seashore spring, which legend says, was brought forth by the Apostle.

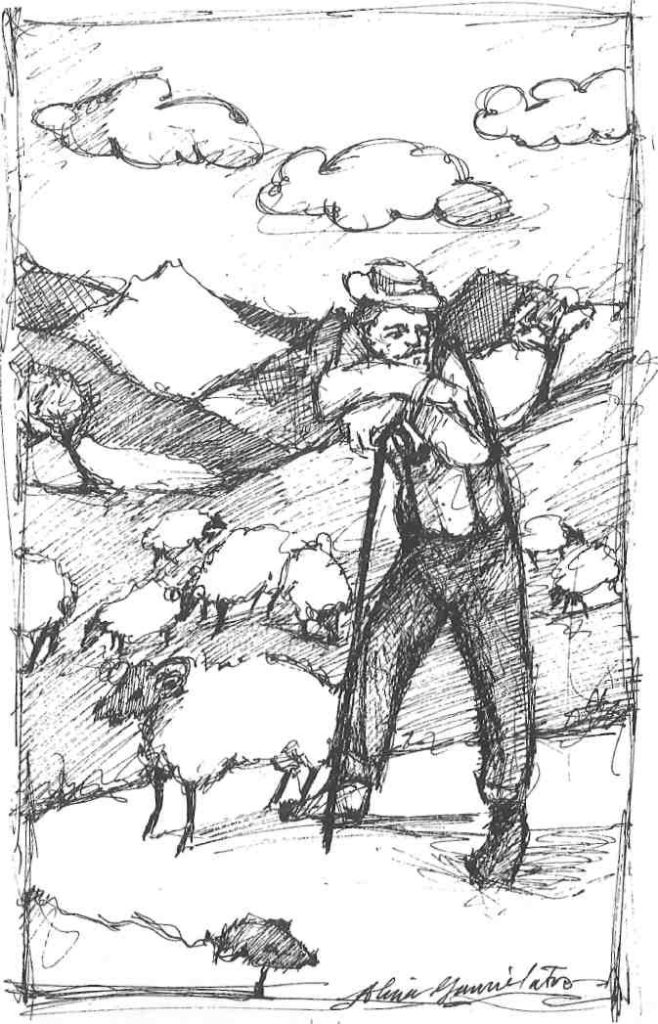

I skipped Rizokarpaso in favor of Aghia Trias, hoping to meet the parents of my monk friend, Hilarion. I was curious as to what makes a monk; they are usually very leery about discussing their past lives in the world, and I reckoned the proud parents would be more forthcoming. I was correct. At dusk I found father. He was’ wearing the olive-drab cloth cap favored by all northern men regardless of ethnic affiliation, and grazing 20 sheep in some stubble. His face lit up when I told him I had lunched with Hilarion a month ago. Considering what he had been through, he was sweet-tempered, Godfearing and God-invoking, very much the father of his son. The family had been well-off in land (most expropriated now), though not conspicuously wealthy. There were two other children in the South, the first generation to complete secondary education.

Ill reality, Cyprus can never be hermetically divided. The challenge, in the event of any settlement, is to forge a genuine island identity that goes beyond such superficialities as left-hand driving.

We and the sheep went home “for a beer” which turned into a lavish meal. Father apologized at length for his wife’s absence. I was wrong about their never having seen their son again. The Karpas Greeks are given week visas to visit the South, escorted by the UN. Now the place was in a bachelor’s mess. But the external dilapidation, he volunteered, was the result of uncertainty: people in both communities hesitate to replace so much as a window pane, though this could be pride covering the shame on not having ready cash for repairs. Indeed, restrictions on Greeks participating in the local economy have resulted in a thing long vanished from the South; subsistence farming, with the Karpas Greeks self-sufficient in most foods except soft drinks and beer. Father plied me with plenty of the latter – “Just one more, hee! nee!” -and I could see a disapproving, absent wife. He also gave me a bushel of his orchard plums which lasted a week.

Father had the retrospectively rosy view of Greek-Turkish relations – “before the hatred started, mind you” – so common to Greeks on both sides of the Line; it contrasts with the Turkish pessimism. The Karpas here had been a mosaic of ethnicity, Turkish village alternating with Greek, though few were actually mixed. Denktash had reportedly come to one of the latter in 1964 to urge the inhabitants to enclave themselves. They refused – then. Hilarion’s father considered that the 1974 invasion and aftermath was God’s punishment for the Greeks’ sins, a traditional Byzantine attitude that has been repeated at intervals since the Turks first appeared in Anatolia ten centuries ago. During the Ottoman period Aghia Trias was the only village in the Karpas where church bells were allowed to be rung. Although Rizokarpaso has a larger Orthodox population, bell-ringing is forbidden lest it annoys the Muslim settlers. Last winter someone stole the tutelary holy picture of Aghia Trias church. It is said to have found its way into the icon collection of the new ‘museum’ at Trikomo.

Near Salamis, the monastery of the Apostle Barnabas, abandoned as late as 1976, has become the finest archaeological museum the North can muster. A few paces to one side stands a modern chapel erected over an ancient crypt, in legend once the tomb of Barnabas, buried here after his stoning by the Jews of Salamis. I fumble for

the light switch at the head of the stairs; this reveals a two-chambered catacomb. On one bench lies a bunch of flowers, not fresh, but only recently faded. I puzzle over this. Greeks sneaking over from the Karpas? Foreigners? It could only be local Turks, revering the cave as they always have. The stratum of belief runs deep in Cyprus, predating the monotheistic religions and not respecting their fine distinctions.

At lunch in Famagusta – a simple pizza oven and soup kitchen – a young man of about 25 at the next table, a propos of nothing, suddenly blurts out, “Have you been to Lefke?” I had – an exotic Turkish oasis with palm tress, almost at the Attila Line. “There are many foreign Muslims there.” I was curious, and pressed him for more. Lefke, I learned, was the power base of a Naqshbandi Sufi leader, Kibrisi Sheyh Nazim, who had indeed attracted large numbers of Europeans, including Cat Stevens. A trained engineer speaking a half-dozen languages fluently, Sheyh Nazim is said to be dangerously persuasive. Dr Kucuk, Vice President under the 1960 Republic, saw fit to jail, then exile him. Since 1974 he is back, and reportedly both Turkish President Ozal and North Cypriot leader Denktash number among his followers.

My last night on the island, I had a leisurely, uninterrupted dinner with Erol. When he came to fetch me, Haris Alexiou was belting out “Mia Pista apo Fosforo”, one of the top Greek songs of 1990-91, out of his car tape system. “A Greek in Istanbul makes them for sale here and in Turkey.” We went to a famous meyhane (ouzeri), favorite of the city’s intelligentsia, at the edge of a desolate area. The ruins are not the dead zone, it turned out, but the result of an EOKA rampage on this Turkish neighborhood in December 1963. They are preserved as a memorial, shown to school kids to keep hate alive.

Between bites of excellent food (it is generally better in the North than the South), Erol gave me the life story of the raffish proprietor, Niyazi. He was an accomplished thief and swindler who had been through four wives. His first misadventure was at 18, when -never having been out of his village -relatives kittied up to send him to England. He disembarked at Piraeus, thinking it was London. Nobody made him the wiser until, three months later and his money gone, the Greeks deported him.

When the first Turkish enclaves formed, the Greeks declared virtually all basic necessities as ‘militarily strategic materials’ and banned their import into the Turkish lagers. (“That’s why they look so poor,” observed Erol.) Niyazi had found his niche in life. With a Greek-Cypriot partner he set out smuggling vital commodities into the enclaves. A lorry shell with a side door would pull up alongside a warehouse loading platform in the dead of night, and have a ‘flat tire’. Up went the jack; in went the booty. They were caught just before July 1974, and Niyazi jailed just west of Nicosia. With the Turkish army approaching, the National Guard sprung the Greek prisoners and they fled together, leaving the Turks to fend for themselves. Niyiazi broke out and hid under some branches in a ditch until the invaders arrived. They paraded him for the papers, gun thrust in hand, under the headline “Brave Niyazi’s Dash for Freedom”. You can still see the clipping, but the woman at his side – wife No.2 -has had her face scratched out by wife No.4. Later Erol put up some of the money to start the meyhane. He’s never seen a dividend, but he gets very cheap nights out. Niyazi is still up to his old tricks. If you like, you can have Anglias brandy from the South; the cases are buried at an undisclosed location.

Erol loves his island with a passion, and, in addition to all his other activities, finds time for political action. Educated in England (a political science major, like his cousin), he is often a member of delegations having meetings with southern leaders. “I tell them ‘If you are really serious about reconciliation you will purge the EOKA-B members still in the government.’ And they keep silent.” Erol equally hates the TLMT (Turkish Nationalist) ideologues lodged in the northern power structure. “And I am insulted when I see the ayyildiz (the Turkish flag) on my soil. Is this an independent country or not? Is the South, with its Greek flags everywhere? Did you know that Cyprus never had a national anthem?” I suspected as much. He hummed a candidate tune, a popular song with lyrics in both Greek and Turkish.

“I often go to the Greek side. The night life is better. I have many friends there.”

I gave him a Karpas plum. It made him homesick for his village in the South which, of course, had the best fruit on the island. And the biggest snakes. All Cypriots are snake-obsessed. It goes back to Mycenaean times, and they tell snake stories the way Americans tell fish stories. I heard about the man in the North who lives in a houseful of them, some poisonous, all tamed; I learned of the mating dances of the black racers, thick as your arm, which – oblivious to circles of onlookers – stand on their tails and copulate for hours. “If I myself were interested in mating, I’d eat more boiled almonds,” he said slyly passing me a plate of them. “You won’t be able to sleep alone.”

We dwelt on past mistakes. “Did you know that at one point Archbishop Makarios offered a passport, air ticket and pocket money to every Turkish Cypriot who agreed to resettle overseas? Anywhere he liked? And that the Orthodox Church granted the equivalent of indulgences to any Greek who bought up Turkish land, even at double value?” I knew this was true from a similar campaign on Imvros which backfired with such dire consequences for its instigators (The Athenian July 1988). “What sort of attitude is this? You (Turkish Cypriots) are 400-year guests! Now you piss off? With the right Cypriots we could make this island a paradise. Instead we have TMT and EOKA.”

As I prepared to leave the North, people on the ground were being steeled, media-wise, at least to contemplate the consequences of previously unthinkable concessions; it felt like the run-up to a settlement. “We won’t become refugees a third time,” a remark attributed to Morfou Turks, was the headline in Kibris the day after American envoys visited the town, presumably to test the waters for just such an eventuality; “Map is in Ankara.” The map in question being Boutros-Ghali’s proposed territorial adjustments, was announced a few days later. Similarly Fileleftheros, a prominent Greek Cypriot paper, is taken up with the peregrinations of ‘The Map’ on a daily basis. In reality, the island can never be hermetically divided, as I learned while there. The regional economies, if not always the peoples, were too interknit when it was under unitary administration, whether British or Republican. The challenge, in the event of any settlement, is to forge a genuine island identity that goes beyond such super-ficialities as left-hand driving.

“Did you know that Cyprus never had a national anthem?” He hummed a candidate, tune, a popular song with lyrics in both Greek and Turkish.

A useful, if unlikely, first step would be to call a halt to continual reference, in visual and literary symbolism, to the flags and agenda of the ‘mother’ countries. It is time to find some fresh local heroes. Despite their economic advantage, it is the Greek Cypriots who are pressing for a final resolution. The Turkish side, even with worldwide ostracization, has more to gain than to lose by persistence of the status quo. Their ‘enclave’ is more generously dimensioned than past ones and has more ways out. All the islanders have their work cut out for them. Bad examples (Bosnia, Lebanon among others) abound, with only Bulgaria’s reenfranchisement of its Turkish community as a recent hopeful note.

With Turkish children still being taught in school that the Greeks will make kebab out of them if either party crosses the Line, and the memorials to those killed by whomever between 1954 and 1975 lovingly tended in almost every village throughout the island, it is likely to be a generation before any significant rapprochement takes place.