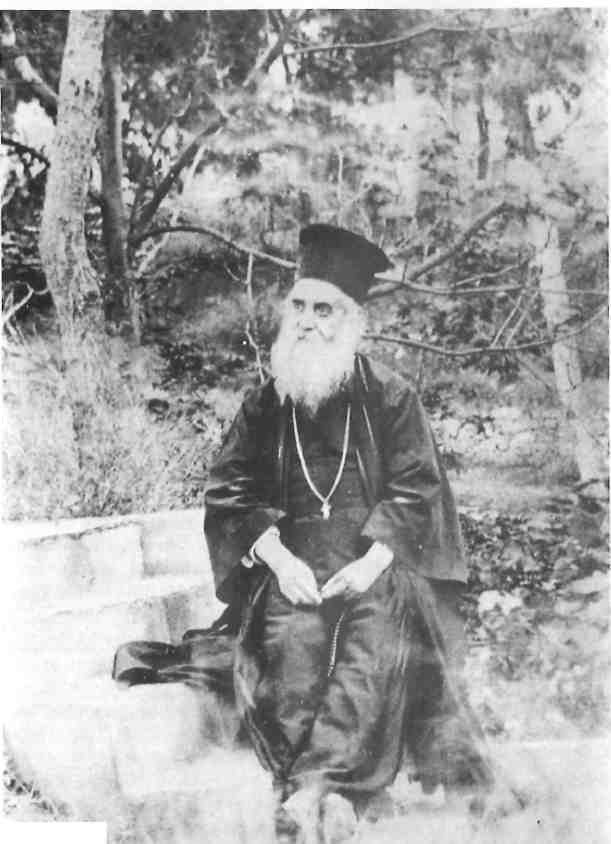

He died in 1920, was canonized in 1961 and his feast day is coming up on November 9. In death, as in life, he wins hearts.

In search of health, the ancients took refuge in the cult of Asklepios. Athenians made pilgrimages to the god’s shrine at Epidaurus, or, after 418 BC, to his sanctuary built on the southern slope of the Acropolis next to a holy spring and beside the theatre of Dionysios.

As Christianity took over, free health care for poorer Athenians was offered by S’SCosmas and Damian. A basilica thought to have been dedicated to them under the name Aghioi Anargyroi (the moneyless saints) replaced the Acropolis Asklepieion.

More recently, Aghios Nektarios has increasingly become the focus of intercession for those suffering incurable disease or congenital handicap. Especially on his feast day, November 9, hundreds flock to Aegina for the celebration of morning liturgy.

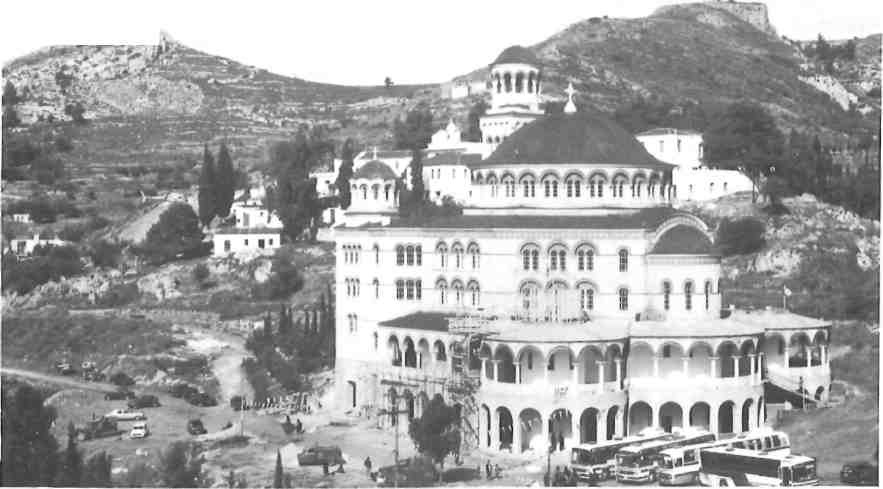

To do their humble uttermost in the way of supplication, some women crawl painfully on hands and knees up the stony path from the impressive new church being built for the saint to the monastery of Aghia Triada. This he established for a handful of young women in 1906.

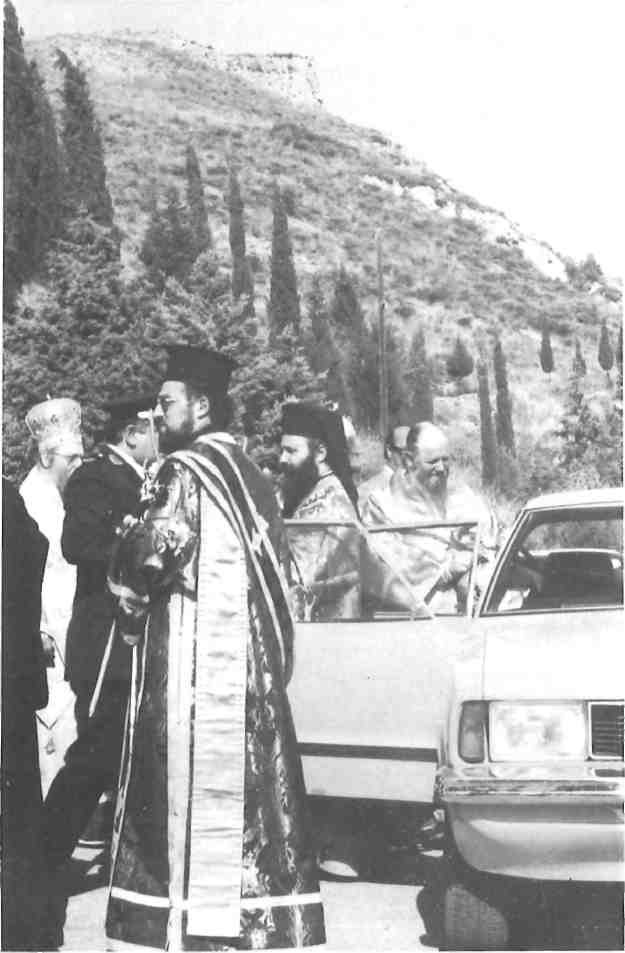

Lofty clerics fly in by helicopter. Nuns meet these arrivals on a rocky landing pad jutting from monastery precincts, hailing the descending ecclesiastics like Shakespearean dukes, “Ah, here comes Hydra,” then “Spetses this time.”

Crowds gather on the cypressshaded monastery approaches, the leafy terraces and flower-laden courtyards, as buses and taxis deliver the faithful from round the island and off ferries and Flying Dolphins.

As the liturgy is chanted by the visiting prelates, offerings of olive oil are made to the church supply. In return, devotees fill bottles with water from the holy spring under an 88-year-old pine tree near where an earlier monastery stood.

Police direct the shuffling traffic moving into the chapel purlieus. The line files passed into the chapel where the saint’s skull lies in an embossed, bejewelled reliquary. After due obeisance, all pass the marble tomb.

Celebrations conclude with a procession (by car and bus) down to Aegina town, where the reliquary and an icon of the saint are carried along the quay to the harborside church of the Panaghitsa. A naval band plays, children parade with flags and banners, colored pennants flutter, and aromatic greenery strews the way. Formal observances over, Aegina tavernas

offer the new season’s wine for sampling with festive fare. It is the last big outdoor occasion till next Easter.

As dean of the Rizareios Ecclesiastical School, now in Ambelokipi, for 14 years, 1894-1908, Nektarios was sometimes dismissed by school authorities as “stuck in the Middle Ages”.

“Doesn’t he ever read the papers?” a committee member asked, deploring his lack of interest in politics. “In an all too political Athens of the time,” it might have been added, “an Athens with abundant demagogues… alive with enthusiasms for the dawning century which promised that science and innovation would deify man.”

He read the papers every so often, said the secretary, “but his main goal is simply to prepare young men for the priesthood.”

“A religious fanatic,” said an official scornfully.

It was acknowledged that Nektarios asserted himself by personal simplicity and virtue. He created a psychological climate of mutual understanding, while being always strictly traditional.

If boys misbehaved, he punished himself by fasting for three days. If the cleaners were slack, he hitched up his frock, went down on hands and knees and scrubbed the bathroom floors himself.

He loved the garden. Boys from rural areas were eager to help, but the board of governors dismissed his suggestion that horticulture be part of the curriculum. A useful asset up the sleeves of village priests, perhaps.

Still, Nektarios won respect by publishing widely on the theological issues of the day, from ethics to the schism between Orthodoxy and the papacy. His repute as a preacher was such that the Rizareios had to issue tickets for the Sunday liturgy. He was mooted as candidate for the patriarchal throne of St Mark in Alexandria, but the royal favorite, Photios of Tinos, won the election.

Meanwhile, the New Testament was published in dimotiki, leading to the November 8 riots in 1901, when eight died, 95 were injured, and the government and the Metropolitan fell.

At the time, Nektarios found himself adviser to a group of five ‘pious young virgins’ wishing to become nuns, but not wanting to enter the convent on Tinos or any others they knew. Support was given by Mayor Peppas of Aegina to revive the deserted monastery of Zoodochos Pigi on the inland hill facing the dilapidated chapels of medieval Palaiohora, the chief city on Aegina for a thousand years, until 1826.

Nektarios blessed the building of a new church on the site in 1906 and corresponded with the novices on spiritual matters. Weary of worldly responsibility, he finally resigned from the Rizareios and moved to Aegina as father confessor of the new convent of 15 in 1908. He was 62.

The move fitted in with the mission he felt to help revive dying Orthodox monasticism. On a three-month visit to Mount Athos in 1898, “studying in the libraries, praying and leading a strictly ascetic life,” he saw the decline in the monastic spirit. At heart he had always wanted to be a monk.

Nektarios worked miracles on Aegina from the first day of his initial visit in 1904, healing 15-year-old Spyros of convulsions and Rena of a haemorrhage she had suffered for six years.

Prayers he led for rain to end a three-year drought were answered by evening, though suppliants were at his door in Athens some weeks later because it failed to stop.

His life itself unfolded miraculously, ever since he left the bosom of a devout family in Ottoman Thrace, aged 13, and went to Constantinope in 1854 to learn to read as the key to Holy Writ.

The ship he had difficulty hitching a lift on had engine trouble until he was let aboard. His fare was paid by the nephew of the Chiot millionaire, Yiannis Choremis, whom he chanced to meet years later, and was thus given finance for high schooling in Athens.

As a Boy Friday for tobacco merchants in Constantinople, he practised writing proverbs on tobacco cartons. Driven to desperation when his clothes and shoes fell to bits, he wrote a letter, asking how to manage, addressing it “To our Lord Jesus Christ, Heaven.” (A Mr Themistoklis was meant to post it and sent the boy a box of clothes.)

After work as a youth instructor at the Church of the Holy Sepuchre in Istanbul, he was sent for study to Chios where his family had moved. At Nea Moni he took the monk’s habit in 1876, giving up his name, Anastasios Kefalas, for Nektarios, “in honor of a venerable patriarch of Constantinople.”

After high school in Athens, thanks to Choremis, he was sent to Alexandria with an introduction to Patriarch Sophronios, former Ecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople till 1870 when he was pressured to resign “due to the various shocking events of unrest that had then occurred in the Balkans.”

Sophronios sent him back to Athens to study theology, which he did thanks to a scholarship, Choremis having died. Subsequently back in Egypt, he was ordained and became archimandrite in Cairo. In 1889 he succeeded as Metropolitan of Pentapolis.

At the new monastery of Aghia Triada, Nektarios combined spiritual direction with the founding of a school and the occupations of building and shoemaking for the sisters. By 1914 the community numbered 24, though threatened with dissolution by authorities in Athens, envious of the success of the venture and its substantial donations.

The Metropolitan, distracted by political attempts for dissolution, busied himself by excommunicating, Venizelos. The latter set up a tribunal to study the act, and dethrone him.

The new Metropolitan outdid his predecessor in embarrassing Nektarios, persuaded by a story from a woman whose daughter had entered the convent that Nektarios had seduced her. Fearing scandal, the Metropolitan visited Aegina and lectured Nektarios, then nearly 70 and seriously troubled by a prostate problem.

The proper state of the convent and the ascetic faces of the nuns convinced the visitor nothing could be amiss. (Medical examination showed the novice intact.)

In the autumn of 1920, Nektarios’ deteriorating health led a friend to bring a doctor to see him. He was ordered to hospital in Athens promptly, a clinic for urology treatment. Two months later, on November 9, not having had an operation, he died, a pious nun by his bed.

“The monastery will become like a brilliant lighthouse, illuminating the sea of humanity. The island will prosper, and the inhabitants will be filled with gold,” he told the nuns before his death.

As he was being laid out, his shirt was put on the bed in the ward next to his. The paralyzed man lying in it stood up and walked. The hospital was startled to learn the old monk was ex-dean of the Rizareios and a former Metropolitan.

Borne back to Aegina for burial,his casket was feather-light and his face exuded sweet-smelling sweat. Fishermen, sponge divers, farmers and labourers vied for the privilege of carrying the coffin. Police organized relays.

Exhumed at intervals, Nektarios’ body remained incorrupt for 20 years. Then its decay provided bones for dissemination as relics. Healings of terminal illnesses were counted among the many miracles credited worldwide to his intercession. He was canonized in 1961.

The Asia Minor disaster had distracted authorities from legalizing the convent’s status, till a former Rizareios student became Metropolitan and authorized formal acknowledgement in 1924.

The recognized spiritual mother, Abbess Xene, “her soul detoxified of every worldly guile,” was surprised in levitation “two metres from the ground” by an insomniac sister visiting the chapel one night.

Today’s community of a dozen sisters are mature nuns, judged fit to withstand the constant flow of visitors. Pilgrims come, not only seeking cures and favors, but from sheer love for the saint. In death as in life, he wins hearts. Novices, though, must go elsewhere for the peace and quiet needed for the early years of monastic life.

Aegina is under the Metropolis of Hydra, whose Metropolitan tries to uphold the example of Nektarios’ life, while directing veneration of the saint to the worship of God.

“Nektarios, A Saint for Our Time,” by Sotos Chondropoulos, translated by Peter and Aliki Los, is published by Holy Cross Orthodox Press, Brookline, Massachusetts, 1989, pp289.