Modern Greeks are probably best known around the world today for their business acu¬men. So successful are they at it, they’ve been called cheats and tricksters, though usually by envious, outwitted rivals. Modestly, Greeks themselves pass on these compliments to the Armenians.

Yet Greek success in commerce is also due to courage, a willingness to take risks, hard work and making the best of a difficult situation. All these admirable qualities show up brightly in the meteoric rise of the city of Ermoupolis early in the 19th century -the first great merchant success story of the modern Greek state.

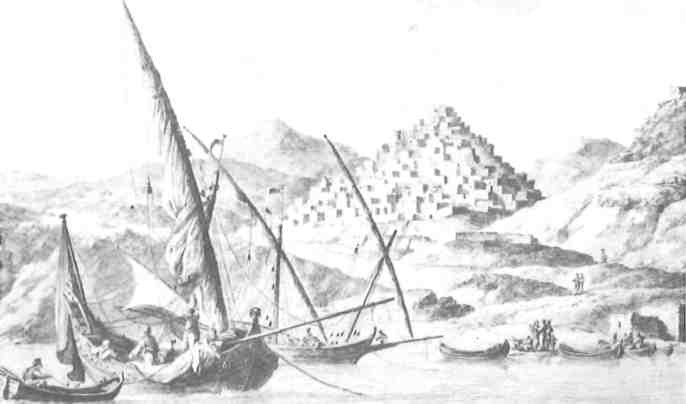

When the War of Independence began in 1821, the existing village, Ano Syra, was an indolent backwash chiefly noted for its slovenliness. “Syra-psira” it was said, jeeringly, “Syra-Iouse”.

“The capital is liker a pigsty than an habitation for Christians of any sect,” wrote Lord Charlemont in 1749. “Pigs and Capuchins are indeed in such abundance here that one can scarcely walk through the streets without stumbling over one or the other of them… It is the most Catholic and dirtiest of the islands.” It is not surprising to learn that milord was an Irish Protestant.

Half a century later, in 1801, Edward Daniell Clarke also remarked on the dirtiness of Syra, but added that the pigs were of excellent breed.

Animals feature in Syra’s rare appearances in history. It played a prominent role in the War of the Ass of AD 1286, a sort of medieval version of the Trojan War with a donkey substituing for Helen. In brief, corsairs abducted an ass belonging to the powerful Ghizi family and sold it to William, Lord of Syra, but as the hind-quarters of the ass had been branded with the Ghizi initials, it was clear where all of it came from. The Ghizi besieged Syra which was then supported by the admiral of Charles II of Anjou and the whole of the Archipelago got involved.

Venice finally forced a peace. The cost of the war was reckoned at 30,000 heavy soldi, but meanwhile the ass had died, and the Syriani avoided paying indemnities – another suggestion that one day they would go far. Alas, there was no blind minstrel around to immortalize these great exploits, and Hopfs Chroniques Greco-Romanes come in a very poor second to deep-browed Homer.

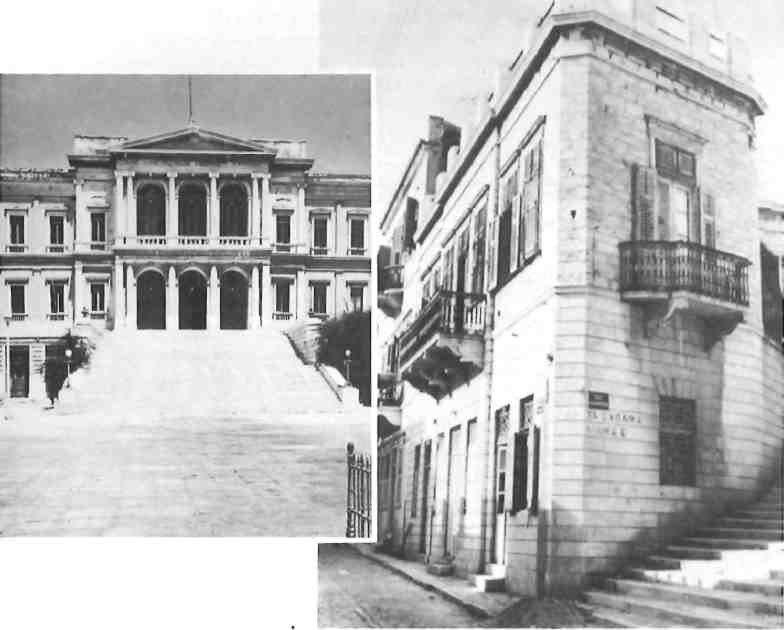

(Right) The Petsas house, 1860.

The Catholic background of Syra, established by these quarrelsome Franks, was to have an important effect on the island’s future rags-to-riches, or pigsty-to-palazzo, story. The Capuchin monks settled on Syra in 1633, followed shortly by the Jesuits. In 1700 the botanist Tournefort visited the island on a fact-finding tour that Lad the personal patronage of Louis XIV. With its overwhelmingly Catholic population and no Turks whatever, the island gradually became unofficially a protectorate of the French kings during the 18th century, an interest revived by the Bourbon restoration in 1815.

In spite of his remarks on religion and hygiene, Charlemont spoke well of the people and, it seems, prophetically, for he wrote “no people ought to be more industrious thanthe inhabitants of Syros.”

No sooner had the War of Independence begun in 1815, that Greeks seeking refuge from undefended islands were attracted to the ‘neutrality1 of Syra, or Syros, as classically-minded Hellenes now call it.

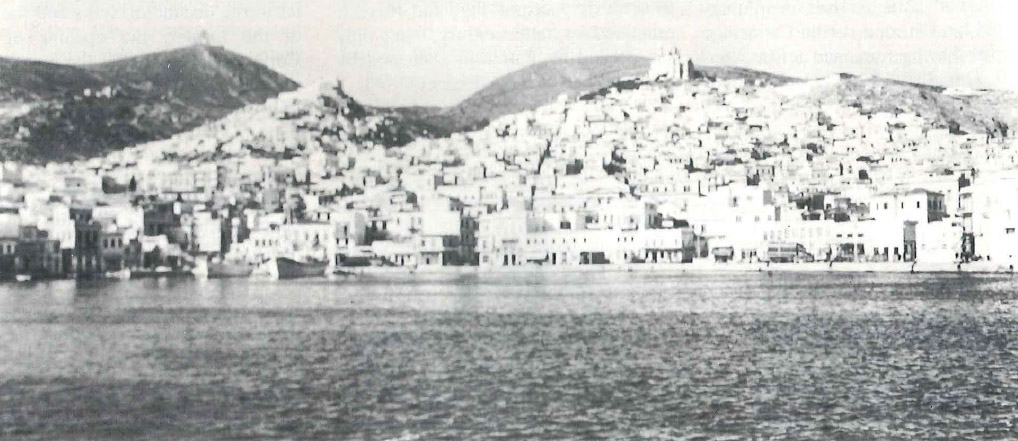

Two of the most catastrophic events of the war, the massacres of Chios and of Psara, in 1822 and 1824 respectively, brought benefit to Syros. Refugees from these most industrious Aegean islands poured in and soon saw the possibilities which it afforded. Lying at the center of the Cyclades and astride the sea route to the Dardenelles, Syros also had a spacious, protected harbor. A further advantage, it had open, uninhabited land around it (the Capuchins and pigs having remained up in Ano-Syra). This allowed for the laying out of a practical commercial town, and soon refugee huts were giving way to proper buildings.

In 1826, the whole community con-gregated before the Church of the Transfiguration to declare the settlement a municipality and to give it a name. It was fitting that ‘Hermes Kerdoos’ (Profit-bringing Hermes) was proposed by a member of the most prosperous Greek entrepreneurial family of the times, Loukas Rallis, and equally appropriate that the whole crowd shouted in response “Ermoupolis! Ermoupolis!” with the same enthusiasm as their distant ancestors had cried, “Thalatta! Thalatta!”

Two years later, when the modern Greek state came into existence, Ermoupolis with 14,000 people, was the most populous town in the country. The capital, Nauplia, was hardly more than a village and Athens at the time was deserted. With the fall of the Acropolis to the Turks the year before, the remaining inhabitants had fled to the hills or the nearby islands.

With the boom that struck Athens when it was declared the capital of the new kingdom in 1832, Ermoupolis had to settle for second city, and there it remained for half a century, being only superceded by Patras in 1880 and by Piraeus later in that decade.

In the development of the city, it is said the Psariots provided the brawn (they made up half the crews) and Chiots the brains (they held most of the key commercial positions).

In 1840, Syros, which had had no ships 20 years earlier, registered nearly 500, half of which were over 30 tons and many built in the yards of this almost treeless island. Here, in 1860, the schooner Monte Cristo was built for best-selling author Alexandre Dumas, and a decade later tugs for the Danube trade (which Greeks dominated).

After shipping (Ermoupolis was called the ‘warehouse of the Eastern Mediterranean’), tanning was the chief industry. Raw hides imported from Europe were exported back processed. Iron imported from England was shipped to European ports in the shapes of anchors, chains, cannonballs and smokestacks. With wheat from Russia, pasta was manufactured and sent to Italy. Cotton from the mainland and Egypt provided such “a prosperous industry that Ermoupolis came to be known as the ‘Manchester of Greece’. This title, however, was soon appropriated by Piraeus. Many factors let to the decline of Syros and the rise of the former: the opening of the Corinth Canal in 1893, the building of the railways, and the concentration of growth, wealth, power (and, therefore, patronage) in the Athens area. The final blow came when Ermoupolis’ merchants themselves began moving to Piraeus, taking their commercial genius with them.

Emerging suddenly when it did out of nowhere and flowering between 1830 and 1890 before going into a decline which nothing soon replaced, Ermoupolis was a kind of 19th century urban miracle which has been called one of the loveliest neoclassical towns in the Mediterranean.

The word ‘neoclassical’ is so general and vague as to cover a multitude of architectural styles (and sins). In Greek, the word seems to include anything standing that has a post-and-lintel structure. Other languages are hardly better, and often it seems to include everything between Baroque and Bauhaus.

There is a style in Greece which, for lack of a better word, is called Othonian’ after King Otto who reigned from 1832 to 1862. Like many things Greek, it has a way of being difficult to define and it may be best described as what it isn’t. Otto was Bavarian, but Othonian is not. It doesn’t have the classicizing spirit of Munich, but it isn’t Empire or Restoration, either, nor Georgian, nor Greek Revival nor Pompeii Romantic nor Roman Risorgimento. If it is closest to Italianate something-or-other, this is because it fits so well into the Mediterranean way of living.

It is an unpretentious, spare, solid, small-scaled style using, against simple, flat surfaces, classical elements and elegant details, particularly in the use of pediments, pilasters, balconies, corbels, roof tiles, acroteria and terra cotta decoration. A very modest house can be Othonian; so can a mansion. The style doesn’t suggest a class; it expresses a way of looking at things.

Ermoupolis is too big to be true to type. The Othonian is only the resident spirit of place. The Big Thing in Ermoupolis is the Town Hall. The Syriani hired the most expensive architect in Greece to create ‘for them the grandest Municipality in the country – and. they got it! Dresden-born Ernest Ziller, designer of the Royal Palace and other splendors in Athens, gave them a fagade worthy of a Roman basilica. The cornerstone was laid in 1874. Today, this grandeur is tempered by a ground floor utilized by -coffee shops. Within, there are two two-storey arcaded courtyards, a Town Council Chamber that has been well-preserved and a museum with some interesting displays of Cycladic civilization.

The Town Hall stands on Miaoulis Square. On the right is the Ladopoulos house (big tanning people) and on the left is the private Hellas Club, designed by Sampo, with an interesting rusticated ground floor.

Behind the Hellas Club is the Apollo Theatre, modelled on La Scala in Milan, built also by Sampo in 1864. Its velvet-covered seats, curtains, huge chandelier and wall paintings, depicting ancient poets and 19th century composers, have all been lovingly restored recently and the theatre just reopened for the first time in 30 years.

Beyond the Apollo’ is the Cathedral of Saint Nicholas. Raised up on a huge parapet and with a long marble staircase leading up to its Ionic portico, it is one of the most imposing Greek churches of 19th century. The windows in the upper storey of the fagade are divided by pilasters with Corinthian capitals and capped by a simple pediment. The soaring effect of the church is increased by two tall and slender bell towers. Within, the iconostasis of white Pendelic marble, with panels of green and red Italian marble on the lowest course, is classical in its orders but sumptuously Venetian in feeling.

In the Vaporia quarter just beyond are some of the most luxurious private townhouses. The Kehayas and Negre-pontis houses, both on Athinas Street, should be noted for their handsome fagades and charming interior wall paintings.

On, or just off, Apollonos Street, running south from Cathedral Square, are some of the finest private houses in the city. Though but one-storey, the Tsiropinas house is magnificent and today houses the Nomarchia of the Cyclades. The Prassikakis (with a portrait of Byron set in a frieze) and the Mytaras houses, both on Apollonos, and the fine Vehssaropoulos mansion behind the Theatre, are worthy of note.

In three blocks, Ermou Street leading out of Miaoulis Square, opens onto the port. Following the waterfront right leads to the Church of the Dormition.

It is the most charming of ecclesiastical buildings with a fine Baroque pulpit of gilt wood and an early icon by El Greco brought by devout refugees from Psara. Beyond are some of the handsomest neoclassical warehouses in the country. If archaeologists ever get their priorities straightened out, they may discover that the commercial neoclassicism of Ermoupolis is on a level equal to the arsenals of Venetian Hania.

Farther south, some of the oldest neoclassical buildings like the Quarantine Station and the Poor House are in a sad state.

Should you be hungry and in the middle of town, go to Eleana, a good restaurant next to OTE near Miaoulis Square. Also in the center is Sirenes, an attractive ouzerie, and 1935 is good, too. Up in Ano-Syra, Kotoa is a picturesque taverna with barrels along the walls and the mezedes are tasty. Piazza is another good eating place.

If you’ve had a surfeit of neoclassicism, medieval Ano-Syra capped by the Catholic church affords a maze of delightful steep, narrow streets. Both the Capuchin and Jesuit monasteries are full of historical interest. In fact, the whole of Ano-Syra has been declared a protected area.

The island, though small and undramatic, affords many attractive excursions, too. Ano Mera is still an agricultural area with fields separated by traditional stone walls.

On the way to and around Chrousa are neoclassical farmhouses verging on villlas while specimens at Delia Grazia may stretch the sense of ‘neoclassical’ too far. It is really Kifissia-by-the-Sea. Kini is a beautiful fishing village and at the tavern Gad you can enjoy home cooking and a panoramic view.

Before leaving Syros, it is a good idea to check out the antique shops. Heirlooms from all over the Cyclades are sent here to be sold. Thrapsiadis near the Cathedral of St. Nicholas is expensive but very good. The Antiques tou Rafailou are centrally located on Kotsovilou Street and Antiques tis Kyras, which has nice, small, easy-to-carry pieces, is on the way to Anafarika, near the Church of the Dormition. Oh, yes, and just before you embark, stock up on some Sanmihali cheeses at the co-operative Viosyr. And don’t forget loukoumia and halvadopita from Kores. (They still make them in the traditional way). And – tell them to hold the boat! – you must get some sausage, too, full of the colors, and odors of Ermoupolis, so that you will carry them away with you to whatever you happen to be going. Then (as Cavafy said of Ithaka),you will always have Syros on your mind.

Further Reading: The commercial aspects of Ermoupolis are well treated in “Nineteenth-Century Syros” by Catherine Vanderpool (The Athenian, October. 1980). uHermoupolis”, a thorough architectural urban study by the late John Travlos and Angeliki Kokkou, published by the Commercial Bank of Greece, Athens, 1984, can still be found in an English excellent translation by David A. Hardy. It has beautiful illustrations, some of which have been used in this article.