I first met Dimitri Papadimos, and his wife Liana when I wandered into their shop, The Caique, on Spetses. I was looking for a small wooden boat to buy as a present. Little did I realize I was about to stumble over a portal into the past. Not only is The Caique chock-full of things from a bygone Greece – old votives, icons, kilims, and wooden handicrafts – but Dimitri and Liana themselves cultivate the easy, refined manner of a more traditional Greece, one few tourists really experience any more.

As we began to talk, nestled in among the hand-painted pottery and rough-hewn wooden tools, it dawned on to me that these were no mere shopkeepers. We discovered, for instance, that we shared a love for the work of the Greek-Alexandrian poet Cavafy, a concern for Greek-Albanian refugees (whom they refer to as the people of Northern Epirus), and a growing anxiety over how many Greeks are sacrificing their rich culture and traditions for the mixed blessings of the modern world.

“I wonder if I belong to this Greece anymore,” Dimitri muses. “Take art, for example. So much of what passes for art today is simply rubbish, and I worry that people can no longer distinguish between art and rubbish. When it is rubbish, we must have the courage to say so!” Over his shoulder, Liana rolls her eyes a little, but smiles and nods in agreement.

Dimitris Papadimos (known professionally as simply ‘Dimitri’) is a self-taught photographer, film-production manager, and something of a poet, though to this last title he modestly demurs. His list of friends, colleagues, and accomplishments over the last seven decades is impressively cosmopolitan. “With a few rascals thrown in for good measures,” he adds mischievously.

He was born in Cairo in 1918, his father in Greece, and his mother was a Greek from Constantinople. It was in Cairo that Dimitri spent his formative years, surrounded by a creative intelligentsia that included painter and set designer Andreas Nomikos, Italian painter Enrico Brandini, and the French painter Salinas.

Scorching summer evenings would find this coterie after work discussing art and politics with youthful enthusiasm. On weekends they would escape to the cooler comforts of Alexandria and the stimulating expanse.of the open sea. It was in this aesthetically invigorating climate that Dimitri first nurtured his love of photography. Then the war intervened.

“I chose to carry a camera rather than a gun,” he says matter-of-factly. Four short months after passing his exams with the Ministry of Press, he found himself covering the war throughout the Mediterranean. He calls it, with tongue-in-cheek modesty, “the most ‘adventurous’ rime of my life,” armed as he was with only a camera in several life-and-death situations.

After the war, he continued to pursue a career as a photographer, only now as a freelancer. In the late 1940s, he travelled throughout Egypt for the Tourist Board, making fast and lasting friendships with the authorities; liaisons which were to prove invaluable in smoothing difficulties later in his film-production work. “I simply stuck with it,” he says. “I knew what I wanted to photograph and I just took the picture. You might say I had a vision, an ‘eye’. But,” he adds with a grin, “don’t ask me anything about the technical side of photography.”

He published his first book during this period: a ground-breaking, black-and-white photo essay on the Bedouin tribes living around the oasis of Siwa, then a paradise, some 550 kilometers west of Cairo, and virtually untouched by the outside world. Done in collaboration with Robin Maugham (Somerset Maugham’s nephew), this book was the first lyrical documentation of the day-to-day lives of these nomadic people, preserving their culture, customs and traditions that today face gradual extinction. It is estimated that nearly 10,000 tourists annually now make their way to Siwa via a newly-paved road from the north.

Soon after the war Dimitri met Liana, though they were not to meet again and marry until the 1950s. They first crossed paths in Athens. He was working with the liberation forces, she with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “I wasn’t exactly sure of him at first,” she recalls. “He was notorious for his informality, receiving lords, ladies, and other dignitaries for their photographic portraits shirtless and barefoot. They were bread and cheese to him,” adding with a laugh, “but for the Bedouin he would dress!”

Back in Cairo, Dimitri met the legendary, even visionary, architect Hassan Fathy. An Egyptian, Fathy dreamt of building affordable housing for the wretched poor of his country by utilizing the centuries-old-techniques of construction with mudstraw bricks. Though it was a vision that met with only partial success in his native land, Fathy earned accolades worldwide -Time termed him the Architect of the Century – and the lasting respect and friendship with Dimitri. “We would travel on photographic expeditions all over Egypt,” he recalls, “and I would never accept any money from him. He helped me build my house in Cairo. He was truly a rare genius and personality,” adding with· a sigh, “and we remained friends all our lives.” (Fathy died in 1990).

Ironically, the end of the war brought the real heartbreak for Dimitri and other Greek-Egyptians living in and around Cairo. In 1952, Egyptian President Nasser, determined to break the yoke of Western dependence, initiated his nationalization policy of pan-Arab socialism making the pursuit of professional careers, indeed life in general, unbearable for any Egyptians of foreign background. Papadimos recalls the period with sadness: “Many of the Greeks were wise enough to begin leaving on their own. There were no political complications for me; but when I realized what was happening overall, when all of my friends began to leave, I felt empty… so I also left.”

While working on a film in Crete, based on a story by Kazantzakis, Dimitri decided not to return to his beloved Cairo, leaving behind a home, all its furnishings, his art and collectibles – even a brother. The film (1956) was entitled He Who Must Die.

Even as he was leaving one part of his life behind him, though, another was opening up. Now based in Athens, he sought work in film production with the same digged enthusiasm that characterized his career as a photographer. In production, his knowledge of languages proved invaluable in coordinating international crews of actors, extras, and scores of others involved in the arduous task of getting a film to the screen. Here, too, the contacts he had made over the years throughout Egypt and Greece facilitated on-time completion of film projects for French, American, British, and Greek productions.

Between these projects, Dimitri found time to publish more books; complete photo assignments for the Greek Tourist Organization; tackle freelance photo work for a variety of Greek magazines; mount one-man shows of his work in Cairo, Athens, Lucerne, and London; and even publish a small book of poetry.

Dimitri and Lawrence Durrell became friends when the latter was writing Bitter Lemons in the late 1950s and they talked politics at length – the emigree from Egypt and the resident of the growingly disturbed island of Cyprus. In 1974 Dimitri was the on-location Greek producer of a BBC documentary devoted to Durrell.

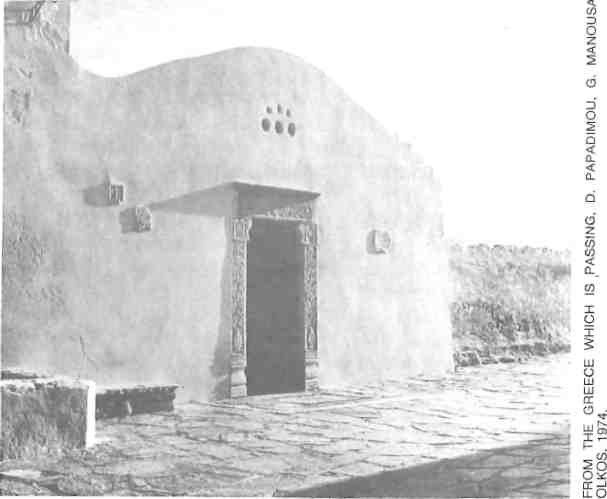

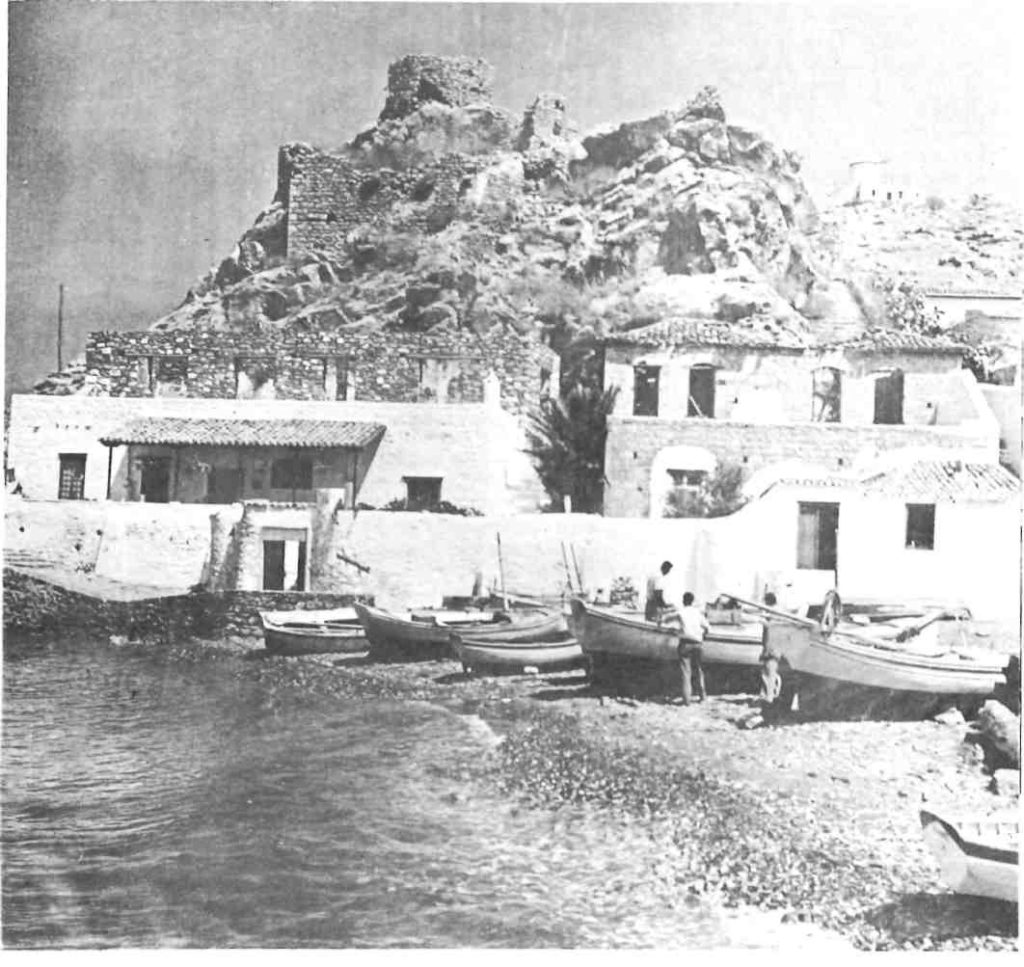

“But do not speak of me completely in the past tense,” he adds. “I hope someday to come out with a fourth edition of the book closest to my heart: Greece Which is Passing.” First published in 1960s, in five languages, this is a work even more pertinent today because it chronicles the temporal beauty of Greece’s landscapes, architecture, and people – a beauty on the wane.

Still, Dimitri remains hopeful; positive about both the present and the future. “In some ways, nothing has changed. You have people who were born in Greece, untouched by the outside world. What I worry about is losing the beauty of Greece for the young; the music, the art, the architecture, the traditions.”

With his house and shop on Spetses, and his wife Liana at his side, two things in life now give Dimitri the greatest joy: that his son, daughter-in-law, and grand-daughter live nearby; and that he and Liana have been able, with the assistance of the local church and numerous friends, to baptize, marry, clothe, and house several Greek-Albanian ‘People of Epirus’ who have made their way to Spetses.

“It is the greatest joy for us to help them,” says Liana. “They achieve a renewed sense of pride, a feeling of self-worth. And we do not always encourage them to stay here, but to take what they have learned back with them. These people have been denied till now the practice of their faith, and have fled their country in search of their ethnic roots – a renewed sense of cultural and religious identity.” “And,” Dimitri adds, “you feel that you are really doing something, without any commercial considerations. You are doing something good, that’s all.”

Liana and Dimitri are also currently working, with the support of the church and the local Spetsian committee Pityoussa, to upgrade and refurbish the island’s local clinic, which is now barely functional. Anyone interested in assisting may contact committee president Doctor Dimitsas at (0298) 72317, or his secretary Effie Zakka at (0298) 73551.