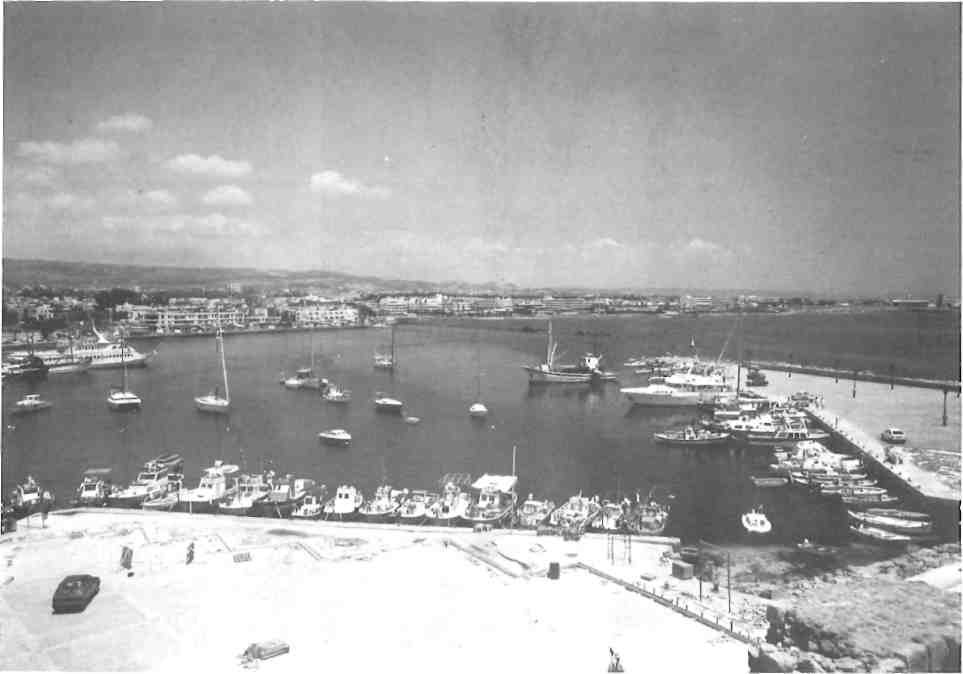

Until this spring, the only time I had ever been near Cyprus was late on a May evening. The Haifa-Rhodes ferry was late, and Limassol harbor had an even more daunting prospect at 11pm than it might have at sunset. With less than 400 US dollars in my pocket, and tales of the country’s astronomical expense echoing in my head, I decided not to exercise my stopover option but to save the island for another time.

That opportunity wouldn’t return until, after years as a writer of travel guides, I was tabbed by my publishers to do a book on Cyprus – the South and the North. My qualifications: I could speak both Greek and Turkish passably well; Ϊ was familiar with both cultures from extended stays in each ‘mother’ country; as a novice to the place, I would presumably have an open mind on the situation; and, not least, I needed the assignment. All concerned were taking the calculated gamble that some sort of political settlement was in the offing that would permit – for foreigners at least – unrestricted movement between North and South, which would remove the stigma of political incorrectness from patronizing the North’s tourist industry.

A gleaning of first impressions: Left-hand-driving Cyprus is very much the ex-Crown Colony; itinerant icecream vans trundle about to a sound-track of jingly tunes; pillar mailboxes flaunt their ‘G(eorge) R(ex)’ and ‘E(lizabeth) R(egina)’ monograms, and assorted specimens of ‘Middle East Raj’ architecture jostle with vernacular neoclassical or mud-brick buildings. There is less tobacco smoking and kamikaze driving than in Greece – at most a single polite toot when overtaking, and cars actually stop for pedestrians at zebra crossings. It’s amazing what three generations of British rule can do…

The privileged of both communities still send their young for higher education in the UK, in preference to Greece or Turkey (considered the preserves of the hoi polloi), though this is no longer strictly necessary since the opening of universities in both zones of the island. Since 1974 the Britishness of the North has been deliberately diluted by the Turkish occupiers and ideologues in the local government, but the public declined to give up the left-hand driving and roadside milestones, while accepting petrol in litres and vegetables in kilos. (The South went completely metric a few years ago.) An Ottoman flavor lingers on with land sold in donums (a little bigger than a stremma) and certain foodstuffs still changing hands in okas (2,8 pounds).

Rare breezes waft the fumes of slightly stale cooking fat just as they have in every other former British possession I have visited. For the humble chip is the tyrant of the Cypriot menu on both sides of the ceasefire line. Strangely, the Cypriots don’t share the peninsular Greek passion for olive oil, perhaps because the island has relatively few trees producing a scrawny, unesteemed fruit.

Cypriots eat marides sprinkled with lemon, rolled in salt, like tequila, and then eaten whole.

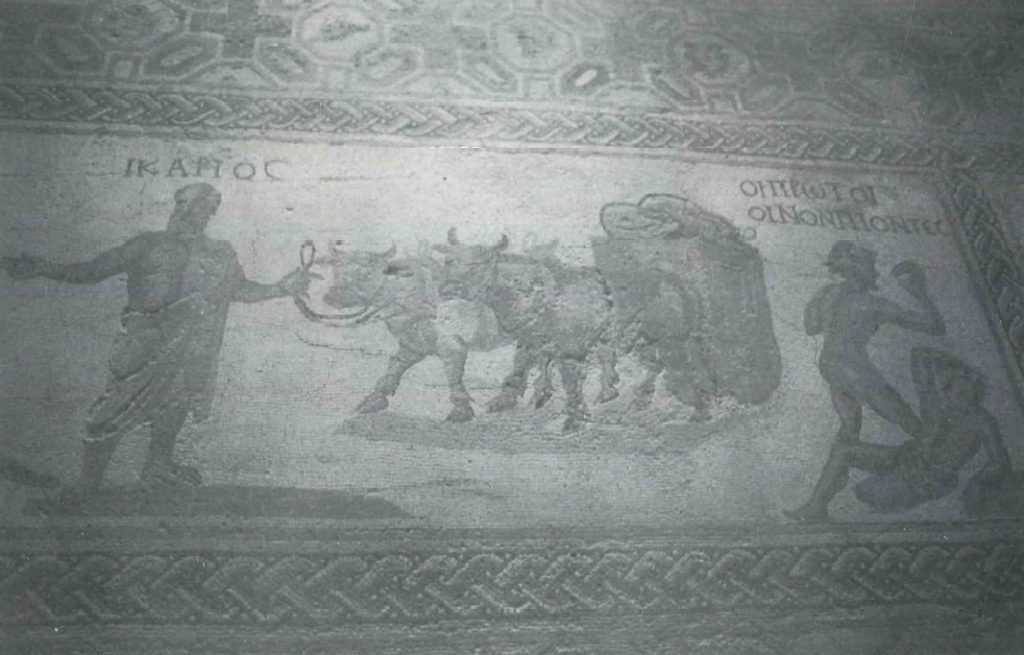

This is a shame, since traditional Greek Cypriot food at home or off the beaten track is interesting and appetizing. From louvia (black-eyed peas) is made louvana, a wonderful pureed soup; coliandros (coriander seeds or greens) is used with almost Mexican abandon; kolokassia (Jerusalem artichoke-tubers) and pourgouri (cracked wheat) should appeal to health fanatics; roka (rocket) and the humble garden weed gJistrida (purslane) adorn the salads of the discerning, and kaparia (caper) plants are eaten pickled whole, thorns and all. The caper could in fact be the national flower, growing from virtually every rock crevice. South Cypriot wine -from four major wineries – and the famous KEO beer are as good as claimed, and in the warm climate the islanders indulgently imbibe, a habit going back thousands of years, as evidenced by the famous Dionysos mosaics at Paphos.

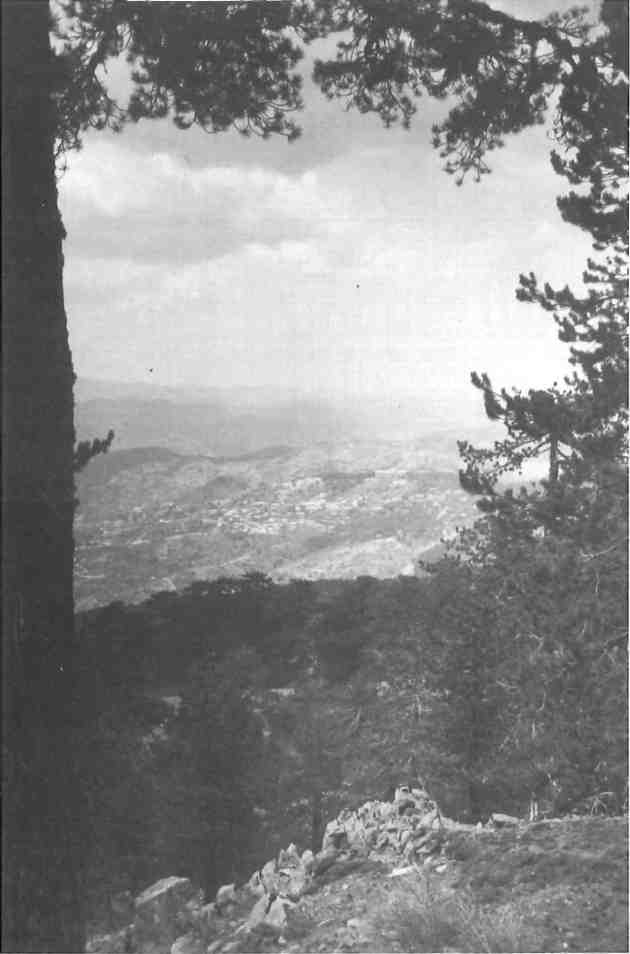

The range of foodstuffs is of course determined by the nature of the land-mass, a complex jumble of chalk, limestone and igneous rock; it strikes you immediately how southerly it lies (34 degrees latitude), the same as Crete, but much more Middle Eastern in climate. Citrus trees flourish as high as 400-500 meters slopes; vines grow at 1000 meters, and frost-tender cedars cousins to the Lebanese variety across the water, hang on up to 1500 meters. Such high limits of altitude would be unthinkable in peninsular Greece or most of Turkey.

My actual wanderings began at one extreme of the island – in all senses, for the Polis coastal plain and northwesternly Akamas peninsula are the remotest and, touristically, least developed portions of the South. The feel is much like that of southwestern Crete eight or ten years ago, with low-impact villa clusters and just a scattering of small hotels dwarfed by the landscape. The cape itself is a vast, sparsely treed and inhabited, tilted plain, furrowed by deep gorges containing precious water. But a storm is brewing over its future; a recent declaration of the peninsula as a national park, largely protected until now by its status as a British firing range, seems only the opening skirmish with the Episcopate of Paphos, which wants to exploit its vast holdings here.

At a simple fish taverna in the area, business was still slow enough in May for the proprietor to chat. He showed me how Cypriots eat marides sprinkled with lemon, rolled in salt, like tequila, and then eaten whole. I mentioned living on Samos, and that we had a Kypraia who ran an excellent taverna there. I told him as much as I knew: her maiden surname, a brother working at a bank in Episkopi near Limassol, the family originally from Famagusta. “I know the father,” he said; I thought he was just being polite, or mistaken, since I had not learned yet just how small the island can be. The restaurant sign said ‘Refugee from Karpas’; I allowed that I planned to go there. Ehei kosmo ekei akoma, there are still people (ie Greeks) there, he replied. It was a telling vocabulary; if the Orthodox were people, or a ‘world’ in the literal sense, what were the Turks?

One day I wanted to call a close friend in Turkey. Its automatic dialing code was conspicuously absent from phone booths, and suspicions as to the impossibility of my wish were confirmed at the Polis post office. I was surprised when the clerk asked, without perceptible guile, “Have you been there? What’s it like?” Despite official policy discouraging such visits, many people beginning with the taverna owner, urg

ed me to have a look at the North, even before I let on that I was required to do so. Certainly there was an element of “Go see the justness of our case for yourself” to this, but perhaps an easing of their homesickness vicariously.

East of the Akamas and Polis, the pine-covered foothills of Tillyria are the island’s most perfect wilderness, despite the Turkish air force having fire-bombed a good portion of the trees in summer 1974. There are no settlements and apparently never have been, except for the forestry station and hostel at Stavros tis Psohas. Tucked in a wooded valley 700 meters up, it is the coolest spot in Paphos district. So a ranger assured me as he sorted a huge pile of edible greens. As I was the only weekday visitor so early in the year, the staff treated me to a coffee while they admired my leather-based daypack and its contents.

The foresters pondered its possible use as game bag; rural Cypriots are such keen hunters that if they were born with pouches like kangaroos, they probably wouldn’t mind. I thought it politic to demonstrate its shortcomings; one of the older guards agreed – Amerikani kanoun skata prammata (Americans make shitty things). Paphiots are known for bluntness, but it was the only overtly anti-American comment I heard in five weeks on the island. Certainly from the Greek Cypriot point of view the US has a lot to answer for.

Had I a pocketknife? As I reached for my Swiss Army model I did a double take: they had used the Turkish caki rather than the usual Greek souyia. The day before, as I asked directions, someone had said catalyolu instead of stavrodromi; I mentioned this. Immediately I learned another application of the Turkish word for ‘fork’ – one wears catalia instead of pantalonia in western Cyprus. Whence all these Turkisms? “From the years in which we lived together,” explained a ranger who looked to have been in middle school in 1974. Studying a demographic map that evening, I saw that Paphos had been the most Turkish-populated district of the island.

I soon came to realize that if they choose to, Greek and Turkish Cypriots can carry on conversations – often by virtue of grammar, not just vocabulary -that are virtually incomprehensible to visitors from the ‘mother’ countries. The same holds true of Paphos district vis-a-vis the rest of the island. Accents on both sides of the Line are nearly the same, so to an untrained ear, the two island languages sound alike. So far as I know, no serious academic study of the Turkish-Cypriot dialect has ever been done. Now with Turkish and Greek TV eroding the integrity of the island vernacular, time ts short.

Accents on both sides of the Line are nearly the same, so to an untrained ear, the two island languages sound alike. Now with Turkish and Greek TV eroding the integrity of the island vernacular, time is short.

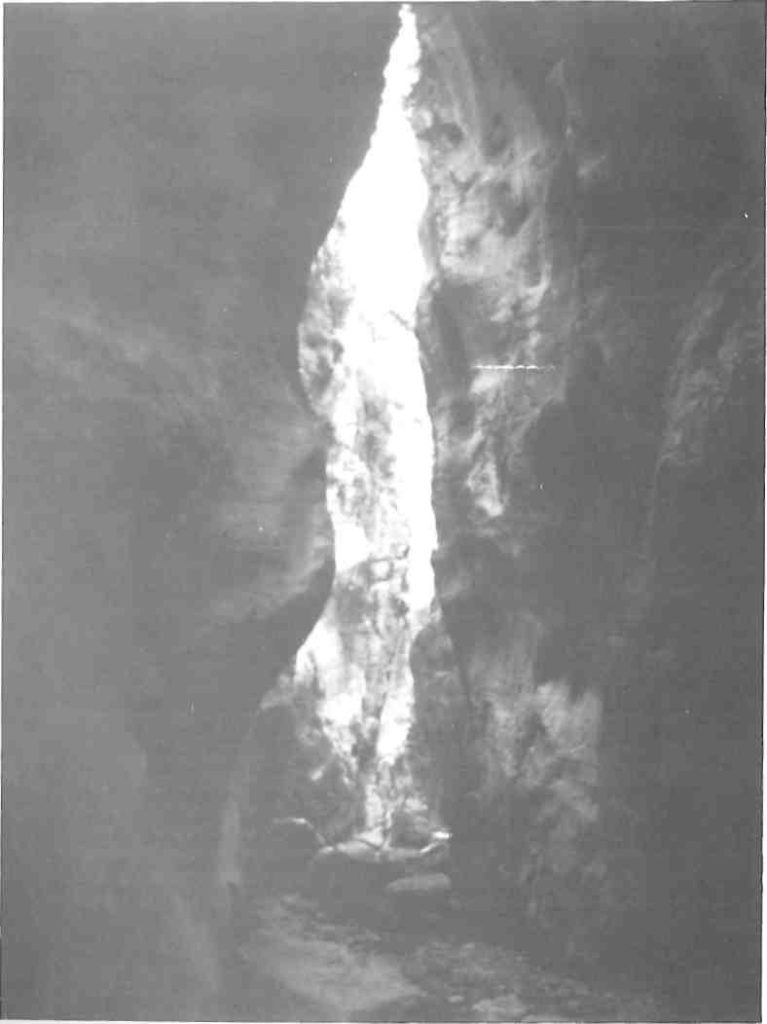

Paphos town itself had been thrown to the wolves of tourism since the opening of its airport in the late 1980s, with a mini-Miami spreading slowly east from its formerly sleepy harbor. The ruins are extensive; the popular sites, such as the mosaics and Tombs of the Kings, more spectacular, but the most intriguing is the catacomb of Aghia Solomoni. She is one of those strangely named saints in which Cyprus abounds, revered despite their often apocryphal nature. A giant tree shading the complex was festooned with hundreds of ribbons, rags and even, in a particularly extravagant gesture, a woman’s night-dress. They are paralled to the conventional metal tammata of mainland Greece and the wax votives of the island. Alternatively, they are said to be placatory gifts to indwelling spirits; I had lately seen identical talismans offered by Muslims at a cave-mouth in Turkish Cilicia, just across the water.

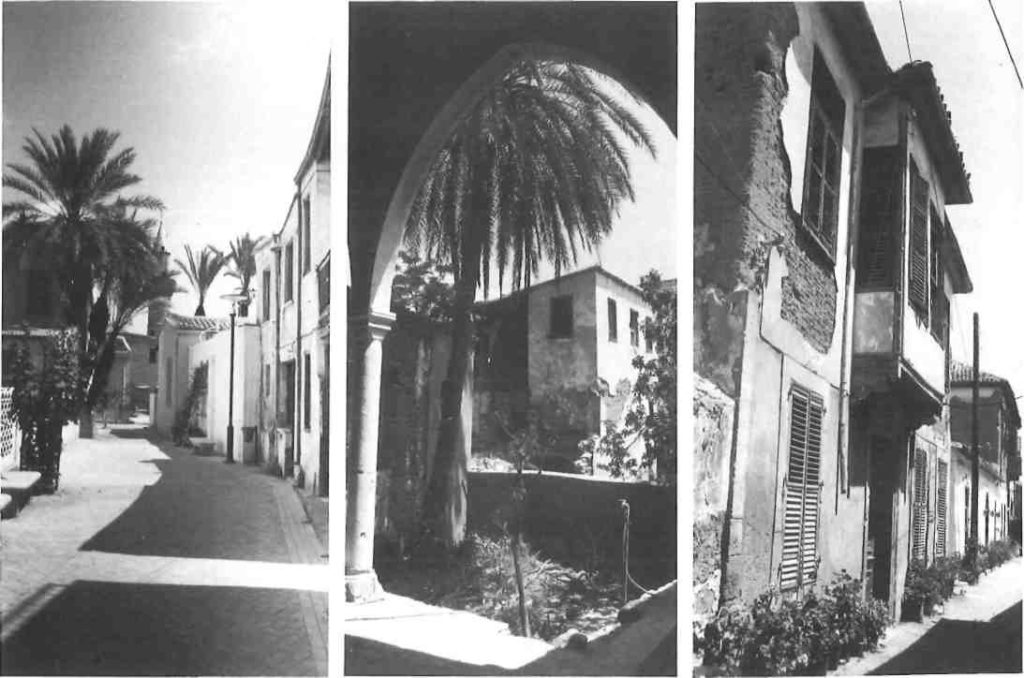

In the upper town of Paphos I came across the slum of Mutallou where the town’s Turks had drawn together after the events of 1963-64. The houses, now occupied by Greek refugees from the north, are shockingly like hovels. I would see this pattern elsewhere -shunted to one end of town, always near the bazaar – though the Larnaca quarter had some fairly substantial houses. The whys of this obvious poverty were more complex than ‘nomadic instincts’ or ‘lack of culture’, the standard Greek retorts, as I’d also learn. A Turkish no-parking sign, and one for a taxi company to Limassol, were faded almost into illegibility, left untouched since 1974. The Greek Cypriots have made a point of leaving the street names unchanged, though a metal arch over the square reading “How Lucky for Him Saying lam a Turk” had been edited with a suspended sign: “We Do not Forget the Enslaved Territories”. Every mosque I saw in the South, too, was in fairly good condition considering the 17-year absence of the worshippers – a consideration not true of the churches in the North.

In fact, the only deliberate desecration I saw in the South was the Berengaria Hotel at Prodromos, of such stately dimensions that it is visible from the beautiful, high Troodos loop trail 5 kilometres distant. Since it closed in 1980, vandals reduced the interior to rubble. Rummaging in it proved as absorbing to a German couple as it did to me. Scattered on the floor before us was an entire social history of colonialism and its immediate aftermath: booking correspondence from Tanzania, Aden, and other less pleasant outposts of the Empire; some uneasy guests in Israel were wooed personally by the manager after independence; an enormous invoice for bar snacks. I pocketed a card that read: “The Secretary and the Committee of the Knight’s Club request the pleasure of your company on the for cocktails from 9pm to 11pm. RSVP”. The frogs swimming in the scum of the abandoned pool were unlikely to respond.

The late-Byzantine churches of the Troodos, with their splendid frescoes, form a remarkable collection of sacred art; nothing in Greece comes close unless those in the churches of Veria and Kastoria in West Macedonia. They are invariably kept locked to protect the interiors, and hunting down the key is an integral part of the experience.

The keepers themselves are a mixed bunch, ranging from the offensively rude priest at Kalopanayiotis who spat biscuit crumbs while telling me to come back tomorrow, to the utterly sweet parish priest at Paleohori who had to stop every 20 yards to introduce his flock to that marvel, a Greek-speaking foreigner. Some were a bit vague as to the identity and the significance of the frescoes; a few times I found myself having to interpret for them. Thematically the images are unusual – featuring such rarities as Nativity scenes with fully seated Virgins or Virgins giving suck. Stylistically, they are hybrid, all dating from the time of the Lusignan Kings when the Orthodox Church was subordinated to the Catholic.

Although after two weeks of covering so much ground by car and foot, I still felt that I hadn’t received any oracular insights on the situation; only what could be gained from inference. The pain of the 1974 evacuation and the homesickness were evident: I could see the signs for prosfighika somatia (refugee associations) and athletic clubs, trying to maintain solidarity with the generation born in exile, for the hopeful return to the municipality in question. But I hadn’t met anyone who could talk intelligently and at length over the trauma of the country.

In Nicosia, things were different. The old city, particularly around Paphos Gate, can be depressing and claustrophobic. An entire district is given over to girlie bars and more discree prostitution; the only other significant industry seems to be cabinet-making. Wall graffiti concern themselves mainly with what is called ‘the National Question’: “Attilas out”, “Federation = Sellout”, or more succinctly, in Hellenic blue, “No”.

The Laiki Yitonia, an area reclaimed from the fleshpots’ eastern fringes, has become a tarted-up tourist trap. In one of its overpriced restaurants, an American voice invites me over. I had seen the woman with her Cypriot companion in Kakopetria, and they me, without speaking. Dimitris, a political science major at a Pacific Northwest university tells a story more interesting than most. His father, a Turk from the Paphiot village of Aghios Nikolaos had tired of rural structures and ethnic politics at an early age. He ran away to the capital, met a Greek woman, and converted to Orthodoxy. The new surname -Theofilaktos (protected by God) – reminded me of the aggressively Christian ones given to Cretan Muslim converts early this century. Knowing well the Turkish Cypriot language and aspirations, he had spent much of his adult life advising successive Southern governments on why their policies were likely to end up in dead ends, to little avail. Confident that this is Dimitri’s element, I plunge in: “Why no settlement after 18 years?”

“Kyprianou had many chances and muffed them; he’s indecisive. It’s not just Denktash.”

“Why would EOKA-B want to assassinate the US Ambassador to Cyprus (in August 1974)?”

“They were angry that the US did nothing to stop the Turks.”

It sounded too simple but we left it at that and went to a boite near the Famagusta Gate, where I heard better live rembetika than anywhere in Athens. Savvopoulos had been there the night before.

We shared a table with Filippos, a childhood friend of Dimitris, a physical education instructor in charge of one of Cyprus’ small Olympic squads. They reminisced over the lost paradises west of Kyrenia. “Back then, miles of empty coves, water like glass…” The day before the coup, newly licensed to drive at 16, they had borrowed a car and started out for a camping and spear-fishing trip in the area, out of touch with the world. When EOKA and Sampson took power, Dimitri’s father, knowing Turkish mentality and what would happen next, went and found them, and made them come home. It probably saved their lives, as two days later the Turkish army landed where they had parked.

The neighborhoods inside the Famagusta Gate through the Venetian walls are the focus of Greek Nicosia’s ‘progressive’ contingent. The bastion itself has been done up as a cultural centre and numerous restaurants and ouzadika – far more authentic than anything in the Laiki Yitonia – are tucked along narrow streets which are the object of extensive urban renewal, as close to the Green Line as practicable.

The Green Line, as the ceasefire line is called within Nicosia, exercises a morbid fascination. I found myself returning to it again and again, trying to follow its length, peering through when out of sight of Greek, Turkish or UN checkpoints. Between these stretches a ‘dead zone’ of derelict, rat – and snake-infested houses, an average of 70 metres wide. Its very existence is a provocation, to which a steady trickle of Greek Cypriots, not all certifiably unbalanced, have responded to over the years. Periodically, groups of women strike out on protest marches towards their home villages, putting the National Guard in the embarrassing role of turning them back (once they got several kilometres into the North). Single men crash the barriers on foot or in vehicles, the most recent attempt last June. A National Guard-post slogan overhead reading “Our frontiers are not these, but the shore of Kyrenia” doesn’t argue for self-restraint.

Near the UN checkpoint at the Flatro bastion, Taverna Thermopiles is a small ouzeri with a mixed clientele. Andreas and Nikos at the bar were both old-towners. Nikos, wise as well as sharp, with a son nearly my age worked as a Kuwait Airways agent at Larnaca airport. Loving his job and Nicosia, he willingly commuted. He was brought up in the mixed neighborhood of Aghios Loukas.

“During the troubles the Turks demolished our church – if you go North, take a look.” (I did; it had been minutely restored as an arts centre.) Was there still any large-scale sentiment for enosis, I wanted to know. “That’s over,” said Andreas, looking down embarrassed. Yet a block away the Enotiko Kafenio, a taverna-cum-book-and-record store is run by a fanatic ‘enosist’ converted from anarchism. There, the souvlakia are more digestible than the politics.

Burly, working-class Andreas, with a machine shop around the corner, took up the thread. He had a grievance: “Ledsky (the US special envoy on Cyprus) says we’ve gotten over it. We go out, drink,have a good time. But you, American, tell Ledsky this. You know Papaflessas? (I did, at least the name.) When the Turks cornered him and his andartes, and it was all up for them, they drank, and sung, and danced, and then marched out to die. This is the party before the last battle.”

He just shook his head. I began to wonder what they had in common, and then it came out: both had brothers who went missing during the Turkish invasion, two of the roughly 1600 Greek Northerners still unaccounted for.

“We last heard from him on August 7 (1974),” said Nikos.

Whatever happened happened. We’d just like to know.”

There had been Roman-style triumphal processions with Greek prisoners in Turkey; might some have been sent to central Asia? Stranger things than any of the 1600 still being alive have happened if the Russians are right in mumbling about American Vietnam-era POWs in the Urals…

Despite this, Nikos seemed remarkably free of bitterness, and hoped for a settlement with reciprocal rights of movement; we exchanged some words of Turkish, which he knew as a native of a mixed district. The proprietor looked sharply at us.

‘There are even still two mixed villages in the south, Pyla and Potamia,” said Nikos, “try and go if you can.” The proprietor, now positively agitated, came over and advised us to cool it.

“There are Turks in this room!” I looked behind me. It was true – on the next stools two big Turks were quietly conversing. Presently they got up and ambled out to a huge motorcycle of the sort beyond the means of most Northerners, and roared off.

The Attila Line is quite porous in a number of ways. 1500 Northerners a day move through the British bases, supposedly for jobs there, but in many cases continue to the South to staff its construction industry.

Vast numbers of vegetables and sheep get through at Pyla too, plus fish caught on the Karpas. Thousands of cubic feet of water are pumped from the underground lakes near Morfou (Guzelyurt) to the chronically thirsty South; in return the Greek Cypriots furnish the North withfree electric current ostensibly as “a humanitarian gesture”, though in fact they know that the Turks would simply turn the water tap off if the South pulled the plug on the North. (The Turkish Army really cooked the North’s goose by destroying a power plant at Aghios Amvrosios in August 1974; a replacement plant is only now nearing completion).

Conversely, the Greek Cypriots still control the water supply to much of Famagusta, piped from the red-soil basin behind Aghia Napa, and every so often shut it off just to remind the Famagustans that they’re still there. In response, the city has overdrawn its few wells so badly that they are now useless, invaded by the sea.

Virtually the only worthwhile establishment in the Laiki Yitonia was an art and antiquarian shop. I bought two engravings, of Epirus of all places, and introduced myself to the proprietor, Loizos, who was up a flight of stairs tutoring his son in science. He had in fact been a full-time physics instructor before opening the shop. An English and a German artists came to visit, then a young Serbian painter on the run from the Yugoslav war. For all of them Loizos opened his wallet and extracted , sheaves of pound notes. I began to get interested; I had never seen a Greek, peninsular or diaspora, part happily with sums of cash.

imbibe, a habit going back thousands of years, as evidenced by the famous Dionysos mosaics at Paphos.

“I commission work to keep a backlog of stock even if there are no immediate buyers. It keeps the artists going too, of course.”

He locked up and we went to lunch. Loizos had lived in England and Greece as well as Cyprus and had brought his penetrating intelligence to bear on all three cultures. First, what did I think of Cyprus compared to Greece? Not so much useless motion, more things finished that are started, in a reasonable amount of time; people more polite.

“The Greeks have become mad dogs. The Asia Minor disaster and the 1940s pushed them to the edge, and the junta finished them off. And they almost finished us too.” Why did he think that the US ambassador was killed by EOKA-B? “He knew too much. Since it was a CIA-supported coup, he was probably their handler and, paymaster. Dead diplomats don’t testify at enquiries.” And why had Kyprianou bungled so many treaty opportunities?

“Because he’s a spineless zero. Makarios couldn’t stand rivalry so he surrounded himself with dwarves; Kyprianou was the chief dwarf.”

Loizos recounted his humiliations at the hands of the Greeks, particularly civil servants. When he got to an episode of trying to clear the body of a friend who had died in England through Athens airport, he choked up, speechless with remembered rage, sweat popping out on his forehead.

“If I’d had a machine gun I would have mowed down those useless bastards standing around pretending to look busy.”

The talk turned to Greece’s neighbors in the Balkans. Loizos’ analysis, interrupted now and then for my opinion or corroboration, was lucid and chilling.

“All this uproar about Macedonia is just a red herring to distract the public from domestic misrule. It’s a non-issue. When the real crunch comes, it will be with Turkey, and they’ll have cried wolf so long that nobody will pay any attention.”

I never made it to Potamia or Pyla; instead, with time running out, I spent a day or two touring the dismally ravished coast from Larnaca to Derinia, just about the worst stretch I had seen in ten years of travel-writing. Colin Thubron describes sleeping on the beach at Aghia Napa in 1972 and being awakened by sand-fleas; were he to find an unpoliced patch of sand today, he would be lucky to sleep at all over the din of nearby discos. Basically, it is not a magnificent coast and would never have become so overexploited but for the Turkish occupation of Famagusta, with its miles of beach to either side of it.

Sunday seemed an appropriate day to visit Stavrovouni, the venerated monastery on an isolated conical hill near Larnaca. Its setting is the main point of interest to the casual visitor. Looking over miles of thin air to the distant sea, I turned to find Father Hilarion inviting me in. “Would you share the trapeza (mid-day meal) with us?” The community was run on the strict Athonite pattern, hence the ban on women beyond the lower gate. I had been to Athos twice in a decade, and told him so.

“And you haven’t converted yet?” he joked gently.

I admitted that I was Jewish, and braced myself for the four-degree drop in ambient temperature that typically acompanies such a confession in the Orthodox world.

“Never mind,” he replied.

“There are all sorts on Athos – French, Germans, even a Peruvian.” And the unspoken corollary: “…who have all repented their errors and embraced the True Faith.”

“Of all Orthodox nations, Cyprus sends the greatest number of novices to the Holy Mountain in proportion to her population.” From experience I knew this was true; the uncomplicated, fervent religiosity of the island co-exists with the veneer of worldliness.

It taps the same current as that impelling the faithful to decorate trees over caves.

Father Hilarion was from Aghia Trias village on the Karpas peninsula, in the North; he had left at age 11, in 1976, for secondary education in the South, and never gone back. His parents were still there; I took their names and address, certain that they had not seen their son since – I might visit, and it would be better than the letters which the UN transmits once a week in each direction.

Tucked in an alley near Aghios Lazaros in Larnaca, the Mavri Helona (Black Turtle) is a genuine ouzadiko, where ospria (mixed pulses). mushrooms, baby crabs, small fish are served until they run out, which would be early, and then one settles for drink. On weekend nights, musicians circulate among the few tables: an accordionist with taped-together glasses, a dissipated guitar player in a funny hat. The rules posted on a pillar, written with a blue felt-tip pen on prelined cardboard, read: 1) No political discussions allowed except for Sundays when the establishment is closed. 2) If you’re a kamaki, there is the beach. 3) If you’re a tough, there are gymnasiums. 4) If you’re ‘beautiful’, there are beauty parlors – and so on until, last but not least: 10) Society has one set of rules, the Black Turtle another.

Paying the modest bill, I chatted with the proprietor. Like most people in the old Turkish quarter, he was a refugee from Famagusta, but ‘I don’t consider myself one, I don’t like to get into that mentality.”

We mused on the latest news in the Balkans and its implications for the island.

“Let it happen. A full-on war is good once in a while, keeps the population down.”

Afterwards I remembered Andreas with his tale of Papaflessas, and the Don Quixotes who charge the Attila Line. Bravado and despair were inseparable.

My departure flight was delayed, not a half an hour as on arrival, but four hours. The ground crew handled irate passengers firmly but with a weary civility that spoke of extensive experience with such problems. From posters I recognized Evrideiki, a locally born pop star, on her way back to Athens (opportunities for club dates and recording in Cyprus are so small that the artistically talented must emigrate). Bored as the rest of us in the waiting area, she lit up; the ground crew supervisor padded over and gave her a fatherly admonition: “No smoking in here, Evridhiki. That means you too.” She put out her cigarette. I tried to imagine a celebrity in Greece, cushioned in his or her cocoon of paparazzi and sycophants, being told to modify their behavior without throwing a tantrum; I couldn’t. And the small social scale of the island, the mutual familiarity, seemed reinforced.

Once in the air, it occurred to me, listening to a grumbling mainlander, how much lower the general decibel level had been in Cyprus; that nobody’s Virgin, Christ or lineage had been violated within earshot of me for three weeks, and that I’d only heard two ‘msdakas* by Cypriot guardsmen at Nicosia’s Green Line, who had good reasons.

In a taverna back in Atffens, I noticed on the wall an old poster of Cyprus with the typically blood-reddened upper portion faded pink, with the slogan “Den Xehnao”.

“Are you Cypriots?’ I asked the couple running it. No, they were from Roumeli, and, gesturing towards the map, observed “We love them, but they don’t love us.”

Remembering Loizos’ stinging indictment, I could think of some reasons why.