For centuries Greece was Europe’s odd man out. Its singularity was even more fiercely pronounced before 1989 when it was the only country that was Hellenic and. Orthodox in a multinational club of Latin and Germanic heritage. But the recent emancipation of the Slavic cultural bulk in Eastern Europe has brought Greece out of the closet. Athens became suddenly a Western metropolis, a new crossroads for diverse cultural and ethnic minorities.

It is no surprise then, amidst such historic upheavals that nations seek out their cultural identity. For Greeks, the need to express the simple norms of life in their villages produced varied and distinguished architectural styles-from the whitewashed cubes in the Cyclades to the red-tiled country houses in the mainland. The quest for a certain expression of Greekness in the fagades and forms of buildings is a persistent open question in urban centres ever since the modern Greek State was formed.

Neoclassicism was the architectural style that flourished in this country in the 1830s and lasted for at least 80 years, leaving behind fine examples that still carry the vision of past generations. If you cannot today classify Athens – or Patras, Volos, Chalkis, etc – as an open-air museum of Greco-Roman revival, it is because such a small proportion (approximately 10 percent or less) of the neoclassical buildings built between 1833 and the end of the 19th century escaped destruction in the post-World War II decades.

Lamenting over spilt milk has never helped except as an example to avoid in the future. The wanton demolition of so many elegant houses over the last 50 years produced lately an over-sensitivity concerning old architecture. Any building that is not a polykatoikia (apartment block) is easily labelled ‘neoclassic’ even if there is nothing ‘classical’ about it. This architectural confusion that springs from wider social concerns, especially among the younger generations, has led to an unprecedented fascination expressed towards pre-war buildings.

Poor as it may be in regards to majestic and large-scale architectural achievements of the recent past (with a few exceptions), Athens can still boast a rare ambience achieved between world wars which attractively combines splendor with decadence. All these buildings that express perfectly the Greek version of the cultural climate of the 1920s and 30s were built by local Greek architects.

It is thus during this inter-war period that Greece watched a new generation of architects grow to maturity. Their memories went back to the later 19th century when Athens was a neoclassical town with Hellenic, Italianate and Levantine ways of life. Their vision foresaw decades ahead when Athens would become a cosmopolitan metropolis bridging three styles: neoclassical, eclectic and modernist.

“Research into inter-war architecture in Greece is ‘new’. It is only 10 to 15 years ago that there was felt a need to study and record all useful information concerning this period and its most prominent figures,” says Professor Nicholas T. Cholevas, a forerunner in the upgrading of this architecture in the cultural community and later on among students, the intellectual elite, and the mass media. Dr Cholevas, who teaches architecture at the Athens Polytechnic, was the first to consider the issue that the end of neoclassicism had not marked the demise of modern Greek architecture. He has made deep and extensive research into little-known archives and private collections, and has come up with remarkable material that today forms the backbone of existing knowledge concerning the life and times of the primary architects of the period.

There are three important currents in Greek inter-war architecture. The Eclectic, or Romantic, movement, which was most prevalent in the 1918-1923 period and had as its main advocates three charming and industrious Greeks who came from the bourgeois class and designed their buildings for the Athenian nonchalant haute bourgeoisie. Anastasios Metaxas was already known and active from the late 19th century when he marbled the ancient Stadium. Later, he designed the Harokopos house, now the Benaki Museum, the Villa Danai for banker Karolos Merlin, which is the present French embassy and many less elaborate private dwellings that expressed his idealism for a sparkling white and romantic Athens of the belle epoque.

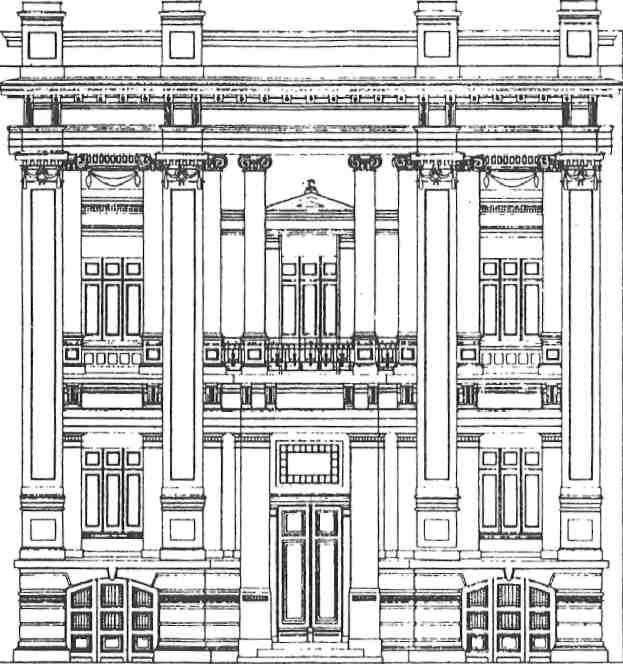

Another well-educated cosmopolitan Greek was Alexandros Nikoloudis, who was influenced by the rich ornament of French origin and who left important buildings from the early years of the century. Let your eye wander over the splendor of the Attikon Theatre (Stadiou, just off Klafthmonos Square) and you will know what Nikoloudis was after. The Armed Forces Club on the corner of Vas. Sofias and Rigillis is another majestic example of Athenian eclecticism by Nikoloudis built in the late 1920s, as is the Livieratou House on the corner of Patission and Ipirou.

Panayiotis Zizilas is less known but all the same his work is important and attractive. Like Nikoloudis, he preferred the rich ornamentation that brought in Athens the fin-de-siecle elegance of a Viennese or a Parisian petit paiais. His most beautiful building, the Samaras House at Tritis Septemvriou 56, was shamefully torn down. Other fine examples by Zizilas can still be admired in Patission; at Stadiou 5 note the Hotel Metropole’s charming balconies with wrought-iron wreathes; at Panepistimiou 54, the Hotel Palladion has four Ionic pilasters on each facade, a festoon and reliefs.

A second movement was expressed by a group of architects who adopted a transitory attitude that left behind all known forms of classic rhythm and produced bizarre and often profoundly composite buildings. They are called the architects who brought Greek architecture from the 19th to the 20th century. Vassilis Tsagris is probably the best known architect of the 1920s. He was very prolific; his buildings excellent.

The Foreign Press Building on Akadimias 23 is one of the finest examples of his work, incorporating successfully the style of Otto Wagner. Tsagris built many private dwellings that are spread over central areas of Athens expressing what was then known as the ‘Tsagris style’.

The Acropole Palace Hotel just opposite the Archaeological Museum is a masterpiece of Sotirios Magiasis. When it was built in the mid-1920s, it was considered ‘the cat’s pajamas’ in its up-to-the-minute poshness. Luckily, it has survived and been declared an , “outstanding example of Art Nouveau architecture in Europe” at a recent UNESCO meeting of experts on the subject. Ail of Magiasis work expressed his high cultural standards and ability to create solid and graceful forms. Most of them, alas, are demolished. Another fine architect of the period was Konstantinos Kyriakides, a Constantinopolitan of aristocratic descent who came to Athens and gradually adopted a progressively modern style that brings us closely to the third group, the Rationalists.

“In all the Balkan States the ‘explosion’ of inter-war architecture comes a few years later after it had been conceived as an avant-garde movement in Central Europe,” said Dr Cholevas. “The Greek architects who brought home the new prevailing climate studied architecture in Constantinople, Paris and in Germany, being exposed to the new language of architecture.” In this ambiguous climate, Athens found its face changed, especially after the ‘flood’ of modernist architecture. These ‘Rationalists’ (Kontoleon, Siagas, Tzelepis, Karantinos, among others) expressed the most mature and characteristic inter-war period style that eschewed all decoration, declaring bare walls and flat roofs as the prerequisite line of ‘correct’ architecture after 1930. It is during this decade that Athens acquired its first really modern architecture. All the then fashionable apartment buildings in Kolonaki, Akadimias, Patission, and the villas in Psychiko were built at this time, bringing new ways of life together with the modern facilities.

If Athenian architecture of the 1930s is not widely known, it is because all tourist guides demurely draw the curtain with the end of neoclassicism. Next time you walk amidst the maze of streets in Kolonaki and Patission, make sure you take notice of the once ultra modern and avant-garde appartment buildings of the 1930s. (In Kolonaki, the Tetenes building at Alopekis 25; the Sklavonos building at Spefsippou and Loukianou; the apartment at Ploutarchou and Ypsilantou).

It would be incomplete if we excluded another important movement which tried to bridge urban and traditional Greece by looking back to the origins of popular architecture. Aristotelis Zachos and Dimitris Pikionis are the main figures of this intellectual, back-to-the-roots movement that embraced all forms of intellectual activity (painting, literature, etc) and is characteristic of all Orthodox countries (similar movements – although earlier -had been formed in Russia).

“Everybody was looking for a certain Greekness,” says Dr Cholevas. “Some found consolation in the architecture of the countryside, some in the tradition of Byzantium, some in classicism, while others broke all bonds and declare themselves ‘Modernists’.” Today, there is a growing interest in this most interesting period for Greece. Athens is full of fine examples that need to be protected and admired. Of course, the Greek capital cannot pass as a major center of inter-war architecture, but a second look reveals interesting and often original details almost everywhere. It might convert a sensitive sceptic into a fervent advocate of the 1920s and 30s Athens-style.