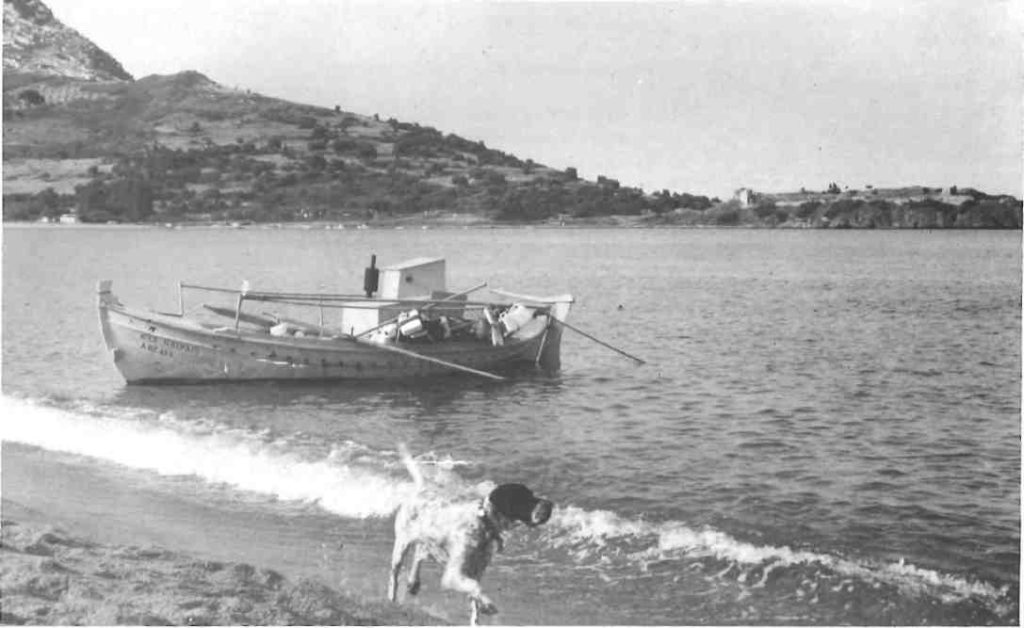

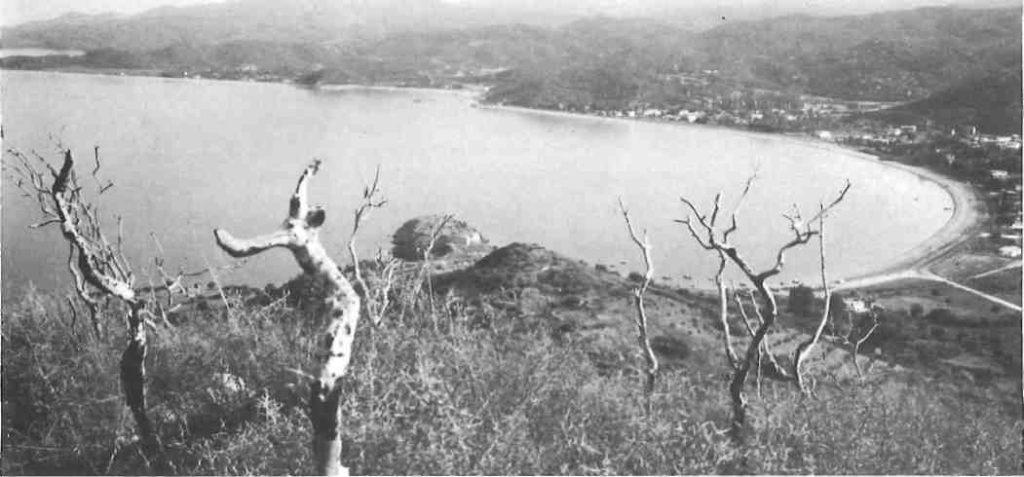

The middle ‘foot’, podi as Greeks call it, of the three-pronged Chalkidiki Peninsula, Sithonia, attracts many holidaymakers, but some bypass the impressive modern tourist attractions of Neos Marmaras and Porto Carras, preferring the simpler beach pleasures of Torone. It is hardly commercialized; there is not even a motor scooter for hire.

Of antiquarian interest out on the promontory, Lekythos, forming the south headland of the perfect C-shaped bay, are Byzantine fortifications. In their stead in ancient times stood a temple of Athena, with a considerable city spreading up the lower slopes of Vigla rising behind.

Scholars know Torone as the scene of a clash between Athenians and Spartans in 424-23 immortalized by Thucydides who, in his narrative of that bloody episode, wrote: “Now there is a temple of Athena on Lekythos. Brasidas, the Spartan general, gave 30 minae to the goddess for her temple, and razed and cleared Lekythos and made the whole of it consecrated ground.”

After two and a half millennia, it has been left to Australians from their distant Commonwealth country a mere 200 years old to discover well-hidden remnants of this long-lost sixth-century BC Doric temple, as well as other architectural remains, a wealth of associated imported and locally made pottery, and other small finds of the fifth and fourth centuries that attest the thriving character of ancient Torone.

The first modern traveller to note the site was Colonel Leake in his Travels in Northern Greece of 1835, but systematic investigation was only begun by the Australians in 1975. This year they mounted their 17th two-month summer expedition to the site. On airborne foray from the antipodes, the team of archaeologists, archivists, conservators, architects and photographers, an accountant, a cook and assistant has spent the last two seasons preparing the publication of their findings. One volume covering the first three years’ excavations should be ready to submit for publication by the end of the year to the Athens Archaeological Society, partner in the venture.

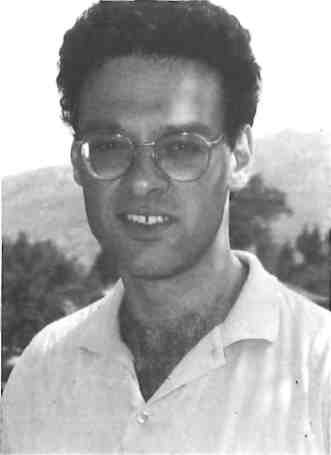

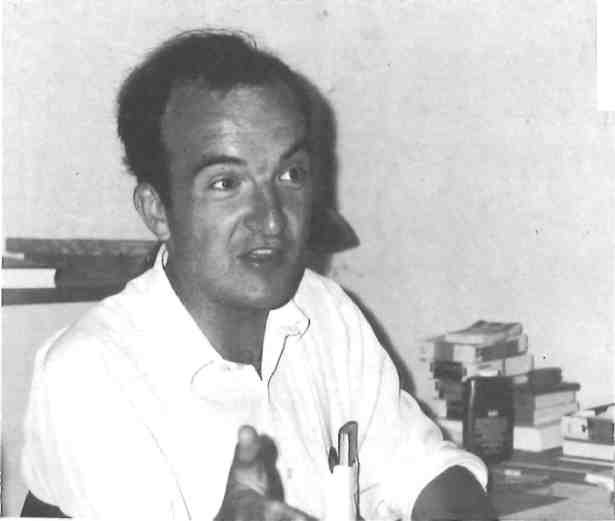

“Chronologically and geographically the site is complex,” says Professor Alexander Cambitoglou of Sydney University, who first went to Torone in 1964 on a tour of Greece in search of potential excavation sites for his archaeology students. With no paved road, the place was an isolated retreat for a few summer fishermen from the inland village of Sykia. “It was a dream,” he says.

Appropriately, Mr Cambitoglou is a Macedonian, born and bred in Thessaloniki, becoming head of Sydney University archaeology department in 1963. From 1978 until his retirement three years ago, he held a chair in classical archaeology endowed by Greek-Australians Arthur and Renee George.

Professor Cambitoglou took up academic life Down Under in 1961 after four years lecturing at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania and two years’ earlier at Mississippi University. As a graduate of Thessaloniki University in 1946, he went on to do an MA at Manchester University under T.B.L. Webster, a PhD at London University under Martin Robertson in 1950, and a DPhil at Oxford under Sir John Beazley in 1958.

The young archaeologist also gathered field experience with leading figures in the Greek archaeology world. At Eleusis he worked with George Mylonas and at Peristeria, a Mycenaean site in the west Peloponnese, with Spyridon Marinatos.

The classical pottery of Greece and southern Italy is his specialty and his publications include a study of Apulian red-figured pottery published by Oxford.

Professor Cambitoglou took up the challenge of the Australian enterprise at Torone after acclaimed excavations of the Geometric town at Zagora on Andros, under the sponsorship of the Athens Archaeological Society, 1967-77. The work there was “unbelievably arduous,” he commented, “because there were no roads to the site, nor a modern village nearby and the area is swept by the strong summer meltemi.”

During a walk along Torone beach on a clear summer morning, Professor Cambitoglou talked of highlights in the various levels of occupation unearthed. He noted first of all Torone’s strategic location, jutting into the Aegean, making a useful port-of-call for maritime traffic from mainland Greece to the Balkans and the Black Sea.

Torone has yielded evidence of Bronze Age settlement dating from the third millennium, he said. Australians have also found evidence of a Middle Bronze Age settlement, unknown elsewhere in Macedonia.

From Late Bronze Age days around the 16th century BC, finds of imported pottery offer evidence of contact with Mycenae, “the earliest known connection between Macedonia and the Mycenaeans.”

A cemetery from the Early Iron Age shows that the site remained occupied at the turn of the millennium.

A large clay-fired pithos from this period was brought to light during the 1989 dig.

Painstakingly restored over the eight-week period this summer, the pithos stood at the end of the season as tangible proof of Australian diligence in restoring Greek antiquities.

After the collapse of the Athenian Empire at the end of the Peloponnesian war in 404 BC, findings show that Torone prospered as a member of the Chalkidic League from 398 till falling under Philip II of Macedon in 348. The city’s subsequent decline could have been hastened, suggested Professor Cambitoglou, by its citizens being removed to populate other areas.

Though few Roman architectural remains have been revealed, Roman pottery finds, a good many from a cemetery, include imports from Asia Minor and Africa. From the 13th century, Byzantine presence is evident judging from architectural remains still to be seen, pottery, coins and other small finds. Occupation continued into modern times.

Over a communal beachside taverna meal one evening this summer at Torone, Mr Cambitoglou recalled conditions at Peristeria: “We had showers once a fortnight and tepid tea and cold boiled eggs for breakfast… People expect more now.”

His volunteer team now flourishes on daily hot showers and meals, including a dinkum Aussie mid-morning smoko snack, produced in the dighouse by a resourceful Tasmanian analyst programmer turned cook for the summer.

But quiet, dedicated application and cheerful cooperation in sometimes tedious chores evident all round suggested old-fashioned standards along with modern amenities.

Visiting consultants on-site this season included the eminent German architect archaeologist, Dr Ernst-Ludwig Schwandner, who inspected the temple remains, and the animal bone specialist, Professor Sandor Bokonyi, a Hungarian who identified a worked hippopotamus tusk from a Bronze Age deposit and a vertebra certainly of a sea mammal, probably a whale, considered a surprising find in the Mediterranean.

“Archaeology is essentially history, not from the written but the material remains of the past,” says Professor Cambitoglou. “Here at Torone we have the remains of religious, domestic and military architecture and small finds such as pottery, coins, terracotta figurines, metal objects like tools and jewellery from semi-precious stones like carnelian.”

The 1992 study-season team was smaller than the 40 strong team of the 1990 excavation group. Among the 26 this year was Dr John Papadopoulos, a Sydney University archaeology department lecturer, previously the Athens-based deputy director of the Australian Archaeological Institute from 1987 till 1991. Team numismatist is Dr Nicholas Hardwick, also a graduate of Sydney University archaeology department, now on an institute fellowship in Athens. He has an Oxford DPhil for a thesis on the coins of Chios.

In Torone for his eighth season, after his first year’s study for a DPhil at Oxford, was Stavros Paspalas, who is specializing in late Archaic and classical pottery of the north Aegean.

Other professionals included Anne Hooton, in charge of drawing, who has worked for five years in a Sydney architects’ office, and other Sydneysiders Tim Martin, an architect, and Ellen Comisky, in charge of photography, from New South Wales state library.

The conservators were Jo Atkinson of Canberra University, and Lisa Pryke, in Athens for a year, a graduate of West Dean College in Sussex, a non-Australian, her opinion of her Commonwealth cousins markedly upgraded by the intensive experience of communal working life at Torone.

Archivists were Joanna Savage of Queensland University, now living in Italy, and research assistant Denise MacKenzie of Sydney. A budding botanical archaeologist, Beatrice McLoughlin, studied grape and grain seeds and olive pits found at various levels, one facet of the attempt to build up a picture of the life of the distant past.

“Pottery provides the basic framework for the archaeological study of a period,” said Paspalas. Local pottery finds on the site are distinctively decorated. “Nothing exactly like it has been found elsewhere in Greece, except at Mende and Polychrono across the gulf. Analysis of the motifs suggests a Chalkidic style, with some elements paralleled in the decoration to be seen on pottery found in Eastern Greece, the Cyclades and Euboea.”

As a sideline, Paspalas studies Torone wine transport amphorae, offering clues to the extent of the city’s trading. The Australian researchers are trying to establish how far afield Torone wine was exported. The area had good pine for cargo vessels and clay beds suitable for the coarse pots have recently been located.

Significantly, Torone coins represented on their obverse a wine amphora, sometimes decked with grapes or vine leaves, or an oinochoe (wine jug), suggesting a wine trade worth promoting, says numismatist Dr Hardwick. Coin finds back up other evidence that Torone had its own mint: the currency is known from many finds, including a horde of fifth-century coins dug up in Lycia, Southwest Turkey, in 1985, and other finds at Olynthos in the Chalkidiki and Egypt.

Of the 400 coins found at Torone, most are fourth-century Chalkidic League and Macedonian bronze: more than 50 one-drachma coins show Philip II. Bronze coins, of the type numismatists call Alexander-the-Great style, are stamped with bow, quiver and club on the reverse and Herakles with a lion’s skin slung round his neck on the obverse.

While from the start the Torone excavations were carried out by an Australian team, the work from 1975 till 1985 was done exclusively under the auspices of the Athens Archaeological Society, of which Professor Cambitoglou is a fellow.

After the establishment of the Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens in 1981, arrangements were made for a partnership, which began in 1986.

Adequate funding has been vital, with 1990 estimates of a two-month excavating season being more than 65,000 Australian dollars and 1992 estimates of a study season approaching 50,000.

The Australian Research Council has contributed to costs, as well as the Institute and Sydney University’s Association for Classical Archaeology, a dynamic group led by Sir Arthur George.

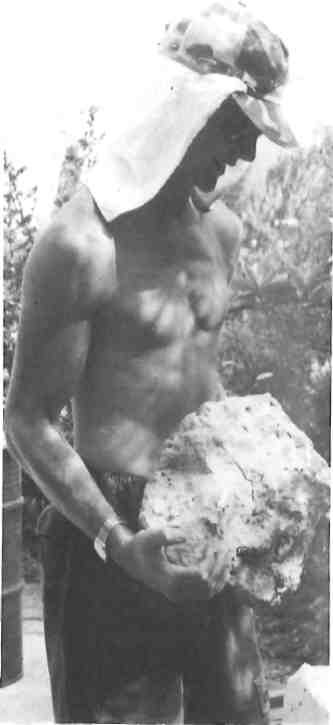

Volunteer participants normally pay about three-quarters of their air fares, except for students like this year’s Scott McPherson, on a Queensland University scholarship. He goes back to reading Roman satire for his BA(Hons) in Latin after truly Herculean muscle-flexing at Torone, heaving round limestone blocks of classical masonry.

McPherson has at least learnt that archaeology is for the fit in body as well as in mind, if unconvinced the golden mean is everywhere applied today in the land that gave the concept birth: but those who carry their flag cannot shirk in endeavour.