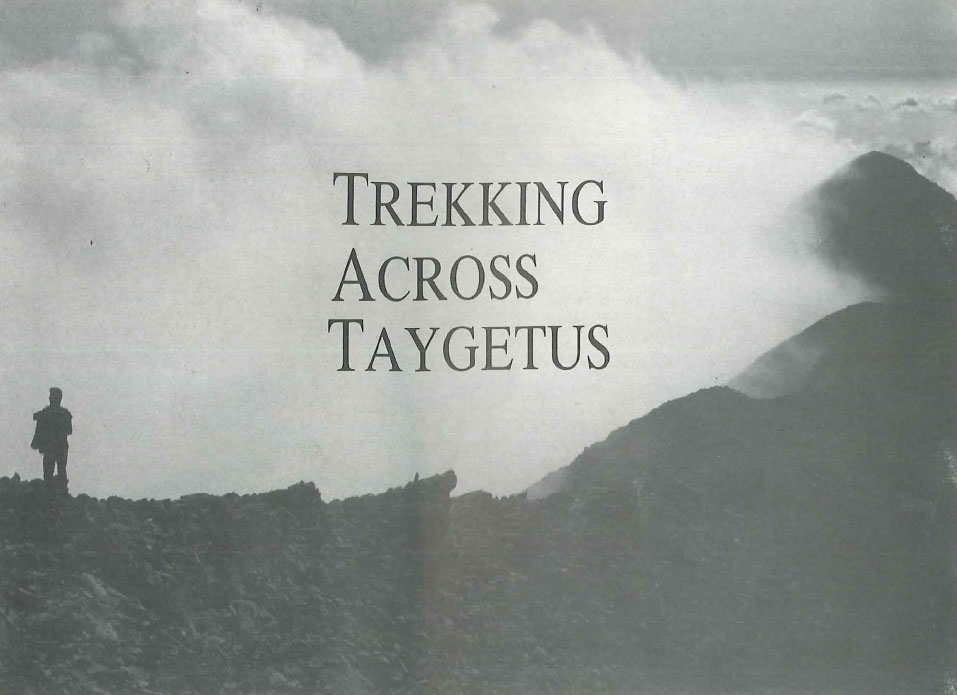

Describing his transverse of Mount Taygetus in the second chapter of his travel classic Mani, Patrick Leigh Fermor wrote: “A wilderness of barren grey spikes shot precipitously from their winding ravines to heights that equalled or even overtopped our own; tilted at insane angles, they fell so sheer that it was impossible to see what lay, a world below, at the bottom of our immediate canyon… It was a dead, planetary place, a habitat for dragons.”

So here I was, possibly on the very same rock that Leigh Fermor had rested his limbs on after the steep and sweaty climb from Mystras. No doubt it was very much the same view: a roller-coaster line of pinnacles and passes soaring and plummeting its way to the south wall of Neraidovouna, the ‘Mountain of Nereids’. On either side of this stone throne the ground dropped away vertiginously to the treeline and, further below, the yellow fields studded with olive trees. Among them the white houses of the village of Mystras, my starting point, shimmered lazily in the distance.

Suddenly the scene came to life as-a passing flock of crows put on a Red Arrows display of whirling and diving. At times they swept by at such speed and proximity that I was startled by the passing swish of wings. Another pair seemed to be engaged in a playful dogfight, but following the action too closely made my head spin. As quickly as they had arrived they vanished quite literally into thin air, and I was left contemplating the eerie landscape at my feet. Bleak and lunar as it was, it was reassuring to know that this spot, unlike so much of Greece today, still provided the same exhilarating view it had done decades ago.

Sitting atop Spanakaki (‘Little Spinach’) Ridge, I was now at the highest point of a three-day trek from Laconia to the Outer Mani, passing over the 2000-metre watershed of Mount Taygetus, the middle prong of the southern Peloponnese.

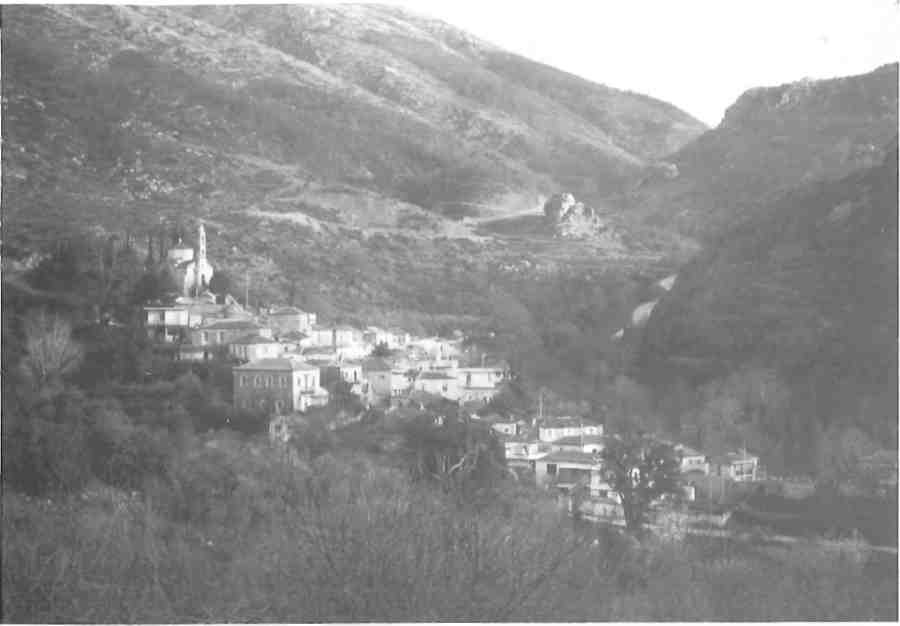

The first day, after browsing round the semi-ruined Byzantine churches of Mystras and making the stiff climb to the Frankish castle that crowns the hilltop, I had snaked my way down to the steep-sided Nerokaria ravine on a dirt track leading from opposite the upper entrance to the site. In the gorge, I gazed up at the sheer rockfaces and pitied any malformed child of ancient Sparta who had had the misfortune to be abandoned here. A well-defined path on the right bank of the tumbling brook led me back to the modern village, a sleepy but picturesque assembly of well-tended houses.

Twenty minutes south along a paved road, I came to the lush village square of Parori. With water flowing down a system of channels in the rock-face, and the shade of two enormous plane trees to relax in, it made an ideal lunch stop – especially as they offered trout. By two o’clock I realized that I was not the first to make that discovery, and by three the square was full of feasting Spartans. I fled up the steep-walled gorge, sure to find solitude there, A right turn at the first fork in the path led to the chapel of Langadiotissa nestling snugly inside a cave. The cool air, the refreshment of cold water dripping on one’s hair and the spectacular overhangs and waterfalls opposite combined in a singular feeling of calm and inspiration, explain why caves played such an integral part in divine myths.

Further up the gorge the clumps of broom grew thicker. The path switched from one side of a concrete water channel to the other, at times so overgrown that I was tempted to walk inside the conduit instead. An hour and a half above Parori the concrete slabs ended in a dry river bed, just below the church of Aghia Varvara. There the dirt track that constitutes the E4 European footpath leads left to Faneromenis’ Monastery, a modern building perched on a high ridge on the left.

The expansive views from here come as a welcome contrast to the claustrophobic cleft of the Langada ravine, but more welcome still was the traditional monastic greeting: a plate of Turkish delight and a glass of spring water. On the outcrop next to the monastery, hefty stones confirmed that it was an old site, but further enquiry elicited only shrugged shoulders and the word ‘old’ preceded by a variable number of “very’s”.

Half-an-hour walk by road leads to the village of Anavryti, which Fermor suggests was founded by fleeing Jews, cut off for a long time from the Hellenic plain-dwellers. But the elderly faces looked unmistakably Greek. Dark, wizened, almost walnut-like, with barely a mouthful of teeth amongst them.

A good night’s sleep at the surprisingly large hotel stood me in good stead for the four-hour walk to the ridge. After half an hour south along the E4 dirt track, a turn right by a bright orange sign (c/o EOS Spartis) leads into the forest. The path made a confident start, but dwindled to a barely perceptible trail after passing a shepherd’s stani and a spring. Instinct and my ‘Korfes’ map advised keeping left of the slight gully which I was following westwards. An hour above the road the trees started to thin out, enabling me to make for a second orange sign which I glimpsed sporadically in a higher meadow that read Imerotopi. This glibly advised making straight for Spanakaki Peak, a mere hour’s stroll away.

Ignoring this optimistic tip, I headed up the right-hand gully to the lowest point of the main ridge. It was still a relentless hour’s slog to the 1780m pass between Koza and Spanakaki Peaks, the northernmost of the five peaks that make up the Pendadak-tylo summit-line. Still, a view like this was enough to resuscitate the weariest Spartathlon runner. The ridge in front of me reputedly took its name, and the mountain its present shape, when Christ grasped it on his climb to heaven, leaving five giant finger-sized indentations; I was presumably situated somewhere under his enormous thumb print.

Lurching down the stony goat trail to the speck which I assumed to be Aghios Nikolaos Springs, I drank my fill of the cold, clean water before settling down to lunch and a siesta. Only now did it occur to me that I had entered Messinia, home of the pointed Kalamata olives and sfela cream cheese. But cultivated fields and olive groves were still a long way off as I picked my way past the increasingly rare splashes of red paint that serve as markers.

Prospective walkers can profit here from my mistake: do not follow the red-dotted trail which contours approximately west from the springs, but head straight down the valley on a network of fine trails. After 45 minutes the two routes rejoin before plunging down the scree-covered gully to the north-south Sopotos Valley. On reaching the ter-races and spring, a good path whisks you left past the deserted settlement of Karia to a junction with another dry riverbed, the Koskarakas. Not surprisingly for such a strategic position, a small church sits on the angle of the banks. This is called Panagia I Kapsadematousa after a dramatic appearance by the Virgin Mary. So incensed was she by the local farmers’ ungodliness that she set spontaneous fire to the bales of hay as they bundled them together!

Not liking to risk a night here, I forked left (upstream) to the tiny hamlet of Rintomo. Cut off from the nearest road by ten kilometers of gorge (maybe less now – a road is under construction from Gaitses), the dozen summer inhabitants lead an even more Spartan existence than their counter-parts in Laconia. Water from the single spring is channelled through a system of terraces before filling up their barrels. Goatskins line the stone benches, goat cheeses hang in muslin bags to dry and goats’ bleating accompanies the evening meal. Keeping livestock and growing crops is their business of life, and only the rubbish scattered carelessly around spoils the rustic idyll.

Night here was magical and serene-simple, tasty food, throat-burning wine and two curious, smiling shepherds for company. Conversation was crudely good-humored, hosts combining surprising ignorance (“Is England part of America?”) with a profound wisdom (“Don’t always seek a reason, some things simply are”) and a phenomenal memory – necessary when you can neither read nor write.

As luck would have it, they were off on a village shopping spree in Gaitses the next day, so my rucksack was soon strapped onto an unladen mule and we set off together down the Koskarakas Gorge. Where the river bed is too irregular for the mules, a broad kalderimi has been constructed along one of the banks. These, the shepherds admitted, were the closest they had come to motorways, and the cliff walls to the city sky-scrapers. At noon I left them beneath the Pigadiotiko bridge, a century-old feat of stonework that spans the gorge at its narrowest point – about five metres. Slipping beneath the moss-lined walls, I braved another 500 metres downstream before climbing the mulepath to the bridge and the open blue sky.

Away from the dark shadows of the canyon the cobbles beat back the mid-day heat with a fierce intensity, and I was delighted to discover a pool a quarter of an hour north (right) on the path to Pigadia village. After a swim, I retraced my steps to the bridge and followed the mulepath south to Gaitses village. Now, it is said, a road has been built just above the path and you are forced to “save yourself the effort” and cut up to the road if you do not want to pick your way over intermittent piles of rubble for two hours.

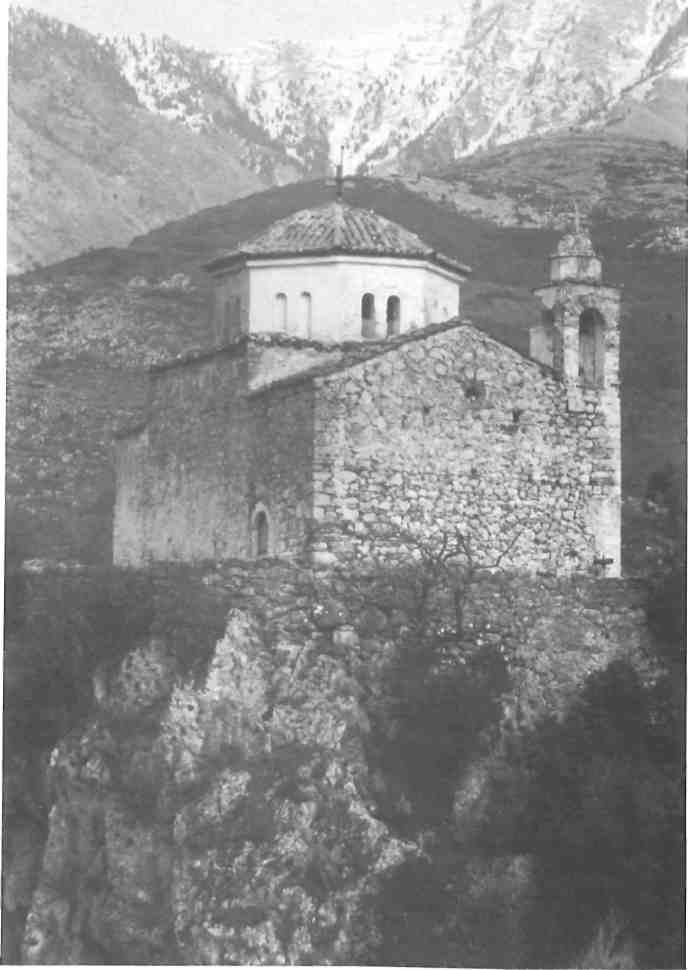

Gaitses village is in fact a collection of four hamlets with other buildings scattered in between. The first sign of civilization is the church of Profitis Ilias balancing on a rocky outcrop directly above the gorge. Again the site is said to be ancient, but locals are hesitant to commit themselves. Amazed at the number of people and vehicles about, I took the dirt road left past Anatoliko (the eastern hamlet) to Kendro (the southernmost and largest), where there are, unofficially, rooms to let.

Two buses a week connect Gaitses with Kalamata, but if you happen to arrive on the wrong day a good morning’s walk can bring you back in contact with the real world. From Profitis Ilias a roughly bulldozed track winds down into the Koskarakas Gorge again, and it is possible to follow the cleft, making one descent on a rickety ladder, to the stone bridge on the Sotirianika-Kambos path. An hour further, or five in total from Gaitses, you reach the asphalt road bridge with four daily bus connections to Kalamata or Kardamyli.

Michael Cullen arranges walking holidays in the Greek mountains, lasting from 2 to 7 days. Staying in villages and monasteries, the groups visit sites of natural and historical interest, and are suitable for anyone with basic fitness, a pair of boots and enthusiasm. There are regular departures to Taygetus and the southern Pindos Mountains in July and August, with trips to the northern Pelo-ponnese and the islands starting again from September. For more information contact him on 8013-672 or via Trek-king Hellas (Filellinon 7, Syntagma; tel. 3234-548, 3250-853).