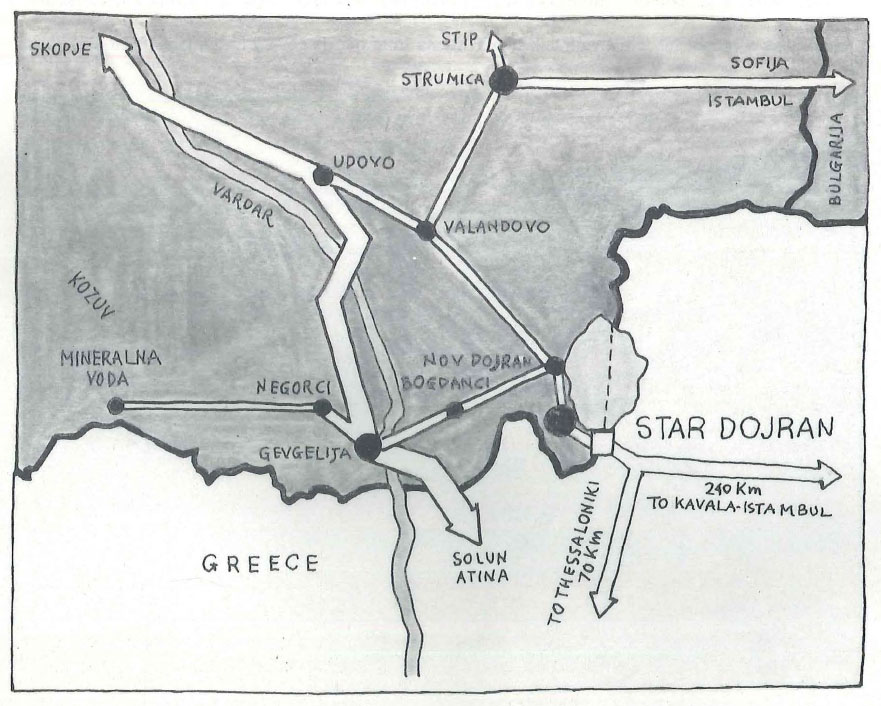

Beside Lake Doirani on the Greek-Skopje border – the hotel and casino managers sit glumly around the empty gambling tables lamenting the loss of all their Greek clients and the collapse of their business. Only a few hundred metres away is the Lake Doirani border crossing point, which along with neighboring Gevgelije until recently was an extremely busy route handling much of the Balkans’ tourism and commercial traffic.

The frontiers between Nato-member Greece and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, once a tense Cold War dividing line between East and West, in recent years had developed into a key communications artery for the Mediterranean and central Europe. But today it is all but closed as the result of an internationally unique dispute over a name.

Greece is blocking international recognition of former Yugoslavia’s southernmost republic, insisting that it abandons the name ‘Macedonia’ as one that is an intrinsic part of Greek history and culture. Its use, Athens says, implies territorial claims against Northern Greece, where historic Macedonia lies, the heart of the kingdom which reached its zenith under Philip of Macedon and expanded into an empire under his son Alexander the Great in the fourth century BC.

The Slavic Macedonians reverse the argument and see Greece’s stand as a Trojan horse tactic for territorial ambitions northwards.

“Our borders used to be one of the busiest crossing points in Europe,” laments Aleksandar Dimitrov, the small republic’s undersecretary of Foreign Affairs. “But the Greeks have now set up a new China Wall to punish us.”

Most evident is the disruption of the holiday and gambling business interests along the borders. “Visiting Greeks were our only source of business, but not a single one comes anymore for fear of being branded a traitor to Greece,” says Mile Nikolovsky, the 30-year-old manager of the Doirani Hotel, which hosts the newest of the four casinos on the border. “I myself, like tens of thousands of my compatriots, travelled several times a year to Greece for shopping and holidays. All that has now come to an end.”

Boris Pavlovski, the manager of a local casino and of a tourism agency, says that up to 2000 Greeks would visit the four border casinos every weekend, providing the area with 90 percent of its income. Similarly, 600,000 Yugoslavs, half of them from the Macedonian region, would holiday and shop in Thessaloniki, only 42 miles south of the border, and in other nearby towns and seaside resorts of Northern Greece.

Though no formal ban has been imposed by Greece on contacts with the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Athens has imposed a partial blockade and alternative communications and business ventures as one means of compelling the new republic to opt for another name. Kostas Pylarinos, Secretary General of the National Tourist Organization of Greece, said a new casino was planned in Northern Greece to attract those Greeks who flooded across the border to gamble. And Greece is developing new commercial and holiday routes through Italy and Bulgaria.

Meanwhile, goods to and from the neighboring republic are turned back if marked ‘Republic of Macedonia’. Visas to visit Greece are cancelled and travellers forbidden entry if they declare their nationality to be ‘Macedonian’.

Customs officials on the Greek side said that a limited amount of commercial traffic gets through, only if the cargo is identified as destined for ‘the region of Skopje’.Skopje is the Republic’s capital of 600,000 inhabitants, and Greece refers to the country as a whole only as ‘Republic of Skopje’.

Greece argues that the Republic is an artificial entity comprising a mixture of diverse nationalities, and that Yugoslav Communist leader Tito truncated it from Serbia’s south so as to limit the Serbian strength within Yugoslav F2derati0n.lt also says the Socialist Republic of Macedonia was set up by Stalin and Tito at the end of the World War II as a base for the ensuing Communist attempt to seize power by force in Greece in the 1945-49 civil war and to exercise territorial pressure on neighboring Greece and Bulgaria.

“There is only one Macedonia and it has been Greek for 3000 years,” says the English-language sticker pasted up ” throughout Greece, inluding frontier crossings.

After a week of interviews in both countries, this writer found that their political leaders and other influential figures felt an almost identical intransigence, suspicion and unwillingness to compromise. Greece’s conservative government and all political parties, with the exception of the hardline Communist faction, vowed in June never to accept any name that includes a reference to Macedonia. But they also pledged not to get involved in war and to guarantee the neighboring Republic’s borders and economic well-being if it changed its name.

The formeiYugoslav Republic counters that it has no other name to go by and will not discuss the imposition of an alternative one by outside forces. It also says domestic political turmoil will erupt if it accepts a compromise.

“We cannot discuss any change in our name, nor can we believe that this issue is Greece’s real concern,” says Jovan Pavlovski, the President of the Macedonian Writers Association. “We cannot but suspect that Greece’s real objectives are territorial.”

As if echoing him in reverse, Christos Batsikas, the President of the Provincial Press Association of Greece, counters: “We cannot even discuss a name which includes the word ‘Macedonia’ or ‘Macedonian’. For we know that by clinging on to this name their real long-term objectives are territorial.”

The new Republic’s government dismisses this, claiming that it only has a border guard army and that its very small size of 26,000 square kilometers is comparable to Luxembourg. Ljupco Georgievski, the leader of the opposition right-wing Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity (VMRO), the largest in Parliament and the one suspected of fomenting expansionist nationalist sentiments, also categorically denied in an interview charges of irredentist plans against Greece.

The United States and the European Community, for the past four months have struggled with a compromise formula for fear that the wars that have swept the former Yugoslav Republics might soon spread to this southernmost region. The two front-running names promoted so far by the EC are ‘Macedonian Republic of Skopje’ or ‘New Republic of Macedonia’.

However, no compromise has been forthcoming so far, as the Yugoslav Macedonians refuse to discuss a name modification and the Greeks threaten the Community with a veto should it dare recognize the new Republic under any Macedonian tag. In Luxembourg in mid-June, efforts by the EC Foreign Ministers again broke down in deadlock, and the issue was deferred for the Community’s summit conference in Lisbon on June 26. After that, responsibility to pursue a solution passes to Britain, which this month assumed the rotating EC presidency.

Stojan Andov, the President of the local parliament, explains that failure or further delay in obtaining the same recognition as that granted to the other Yugoslav Republics could have disastrous consequences on the small state. He says it could facilitate intervention by Serbia, which sees the area as an extension of its own territory, or could further encourage the trend for independence among the very large Albanian population in the country. Furthermore, he says, without recognition the Republic cannot make international agreements and hope for desperately needed economic aid.

“We assure Greece that we do not intend to make any move or alliances that would in any way be interpreted as a threat to it,” Mr Andov said in an interview. “To the contrary, Greece must help us, for it has to realize that failure to obtain recognition might lead to an outbreak of war that would bring in the Serbians, Bulgarians and Turks, and ultimately the Greeks themselves. It is in Greece’s long-term interest to help us survive.”