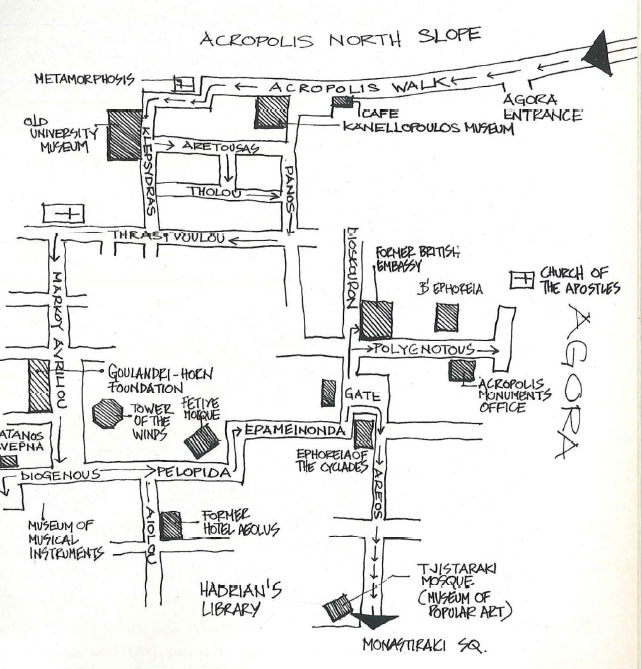

At the exit from the Acropolis site, take a right and then another one at a small building labelled ‘Cloakroom. Left luggage’ and follow a paved walk that gradually descends the northern slope. About 200 meters along, there is a cafe with a pretty view over the Agora. By all means sit down and have a long cool drink. You deserve it. Note the panoramas across Athens all the way down, but watch out, there are steps in unexpected places. Yes, but unexpectedness is one of the charms of Plaka…

Just beyond, where the path widens, there is a prominent three-storey villa at the top of a flight of stairs. This neoclassical building houses the Pavlos and Alexandra Kanellopoulos Museum. A perfect antidote to the Acropolis, it is a monument devoted to the minor arts. The interesting collection dates from Hellenistic times down to the early years of this century.

The icons on the ground floor are old and unusual representations of Byzantine art. Especially noteworthy is a Martyrdom of St Paraskevi showing the strong influence of the Venetian Renaissance. The saint’s silent torment at the moment of death is eloquently rendered, despite some damage, by Michael Damaskinos, the famous Cretan iconographer. Note also the 14th-century Last Judgement as well as the Dormition of Saint Ephraim of Syria, a 16th-century work rich in narrative imagery. A fine winged John the Baptist with the instrument of his martyrdom axed into a tree is a remarkable Cretan work. A case devoted to Coptic art has interesting textile fragments and a wooden statuette of a Madonna and Child is a mini-masterpiece.

On the top floor there is a very fine collection of small lekythoi. Tall and slender with a single handle, these vases were popular in Attica and Euboea during the Golden Age. Their milky white glaze and delicate drawings have a very special lyric beauty. Frequently called ‘the flowers of death’, they played a role in funeral rites and were placed beside the dead.

Two cases of rare Boeotian figurines deserve attention. The antithesis of the art of neighboring Attica, the style is full of fantasy and humor and shows a great flair for depicting animals.

One of the highlights of the Museum is its collection of Tanagra figures – small terracottas of the late Classical period of elegant women gracefully posed in finely draped apparel. Some have elaborate hairdos; some wear a pilos, or cone-shaped hat; others hold a fan or a scroll. Everyone of these fashionable women, exuding beauty and charm, is different; like all haute couture, no two are quite alike. Originally, they were painted in vivid colors which time, with a few rare exceptions, has erased: pale blue or pink robes, red shoes, yellow hair.

Leaving the museum, continue along the path you were on to the minute, delightful post-Byzantine chapel of the Transfiguration (Metamorphosis).

Then turn down Klepsedras Street. On the right is the entrance to the Historical Museum of the University of Athens.

On the left, enter cool trellis-covered Aretousas Street, then down the few steps on the right and left again on Tholou.

At Panos, turn down right and then right again into Thrasyvoulou, a tiny lane named after a mighty warrior No. 9, with its broken storeys, helter-skelter tiled roofs, flights of steps, spiral stairs and masses of greenery is typical of Plaka’s charming habitations. Always keep an eye out for peeks into cool open courtyards sparkling with luscious plants and up at terraces laced with jasmine and grapevines.

Turning left into Markou Avriliou (Marcus Aurelius) Street just under the church of the Dormition of the Virgin, you come to a park. In it, on the left, is the famous Tower of the Winds; on the right are the two handsomely renovated houses which comprise the Goulandris-Horn Foundation, a cultural and spiritual centre founded by the late benefactress Anna Goulandri of the well-known shipping family and her husband the actor Dimitris Horn.

bow is the oldest artifact in the

Museum of Greek Popular Instruments.

Just below and ahead at 1 Diogenous Street is the handsome neoclassical (1842) Museum of Greek Popular Instruments. Its pretty garden on the right abuts onto a small square with a plane tree, a eucalyptus and a famous taverna, Platanos, an old favorite of the Athens art world. A plaque marks it as the former atelier (1922-28) of the painters Periklis Vyzantios and the sculptor Fokianos Rok.

The museum, which is also a centre of ethnomusicology, contains the unique collection of Fivos Anoyiannakis who has travelled throughout Greece studying traditional music and collecting these remarkable instruments. Representing 40 years of research, it is a rich trove for native and foreigner alike. Opened to the public only a year ago, this state-of-the-art museum was first the home of War of Independence hero and poet Lassanis from Kozani who was awarded the house by the state for his valor. On his death (1870) Lassanis left a request for an annual competition awarding prizes for the best tragedy and the best comedy on a national subject.

“Musical instruments that traverse time and space through myths and rituals, uses and techniques.” So the core of the collection is described. Divided into four classifications, the items are beautifully displayed in air-conditioned rooms, under glass cases with interestingly arranged informative material in Greek and English. There is also an audio system whereby one can listen to the music from a particular instrument.

Don’t overlook the reproductions of lithographs which trace the origins of some instruments back to the 4th century BC. For instance, the pandoura, a tricord instrument dates back to antiquity when it was popular, it is said, with centaurs. During the Byzantine period, it reappears as thramboura on a 16th-century fresco on Mount Athos. In the 20th century, as the chief instrument of rembetika music, it is back again, now known as the bouzouki or baglamas.

The oldest instrument in the museum is a graceful, pear-shaped Cretan lyra dating from 1743. Its bow is lined with tiny pellet-bells which kept rhythmic time to the song. The collection of lyras, generally, is stunning.

Along the stairs leading to the lower level – where there is a wonderful display of bells – a laterna (barrel-organ) comes to life with a gay tune. Here, if you are lucky, you will come upon Mrs Myrsini Katsinavaki, the charming and knowledgeable curator. Not only will she guide you through the collection, but she will also show the serious viewer a selection of instruments which are kept in a special temperature-controlled room and may be examined in detail and handled. Separate from the display floors, there is a shop which sells books and cassettes of traditional Greek music, and a lovely garden where concerts are performed in summer.

After this musical interview, cross the street and enjoy one of the antiquity’s most beguiling remains, the marble Tower of the Winds, subject of thousands of prints and watercolors yet never stale to view. Built in the time of Julius Caesar, it functioned as a hydraulic clock. Around its octagonal frieze the eight personified winds forever refresh the observer. Here one may enter the Roman Market.

To the right of the Museum of Musical Instruments is the picturesque entrance to the Medrese, an Islamic seminary, later converted into a prison. Over the gate is the date 1721 and the name of its founder, the Honorable Mehmet Fahri. Just next to the neoclassical house across the street, at Aiolou 3, a rather ill-restored building once housed the elegant Hotel Aeolus, the first hotel of modern Athens. (“Breakfast is provided with tea and other infusions. Meals are served in both the European and Turkish styles,” reads an early brochure). A grille over the door carries the date 1837.

Further along on Pelopida Street, beyond the Tower of the Winds, is the Fetiye Djami, the city’s oldest mosque, a lovely cool corner of Islam. It was built in 1456, only three years after the fall of Constantinople. Today it is used (Polygnotou 10) and next to it the Technical Offices for the Conservation of the Acropolis Monuments (Polygnotou 11). That rather unassuring building on the corner of Polygnotou (Diaskourou 4) is interesting as being the first British Embassy in Athens. Nor can much be said for the prominent building in front of which is the Ephoreia of Byzantine Archaeology. Small and charming, however, is the office of the Ephor of Cycladic Antiquities right in front of the Market Gate at Epameinondas 10. Between the two is a lovely sweep of view south to the Observatory up on the Hill of the Nymphs founded in 1842 by Baron Sina; that higgledy-piggledy jumble of grey and white domes just under it comprising Aghia Maria, to the left, nearby, the Church of the Apostles and on the right the Thiseion.

This view becomes indelibly printed on the memory, fortunately, as it is time to go back into the center of Athens. A right turn down Areos Street leads you directly into Monastiraki Square.

The Goulandri-Horn Foundation with the Museum of Greek Popular Musical

Instruments at the foot of the street, left

Aiolou 3 once housed the first hotel of modern Athens, (1837) the elegant Hotel

Aeolus

At Dioskourou 4 is the unprepossessing facade of the first British Embassy in Athens

View towards the Fetiye Mosque with the old Platanos

taverna, left, and the garden of the Museum of Greek Popular

Musical Instruments, right

Icon of St John the Baptist (17 C.)

Kanellopoulos Museum