On 22 October, 1946, four British warships, Mauritius, Saumarez, Leander and Volage, sailed from Corfu harbor bound, it was said, for Cephalonia where a naval regatta was to take place. They sailed north through the narrow strait which separates Corfu from the rugged mountainous Albanian coast. The previous year this international waterway had been swept clear of mines laid by the occupying German army at the end of World War II, and was open to all shipping.

The war had left the Balkan countries half in ruins, financially bankrupt and politically unstable. Communist-led partisans had, to the dismay of Western governments, seized power by force in both Yugoslavia under the Croat, Tito, and in Albania under Enver Hoxha. Meanwhile, Greece was simmering with incipient civil war. Wartime Allies had become ‘Anglo-American Imperialists’ whose every action was viewed with growing suspicion.

Some months earlier there had been a surprising, unpleasant incident, believed at the time to be an isolated one when two British ships, the Orion and the Superb had been fired at from the Albanian shore while they were cruising through the straits. There had been no damage or casualties, but the British government had strongly protested. Now as the four warships, led by the Mauritius, approached the channel, the crews were placed at ‘action stations’ and ordered to return any hostile fire. All appeared quiet and normal when suddenly there was a great yellow flash, a tremendous explosion and the Saumarez was blown half out of the water. As the Volage just behind went to its aid there was a second explosion, so great that it ripped off the ship’s bow structure. Momentary chaos reigned with smoke and debris everywhere. Sporadic hostile fire they had been prepared for but not mines.

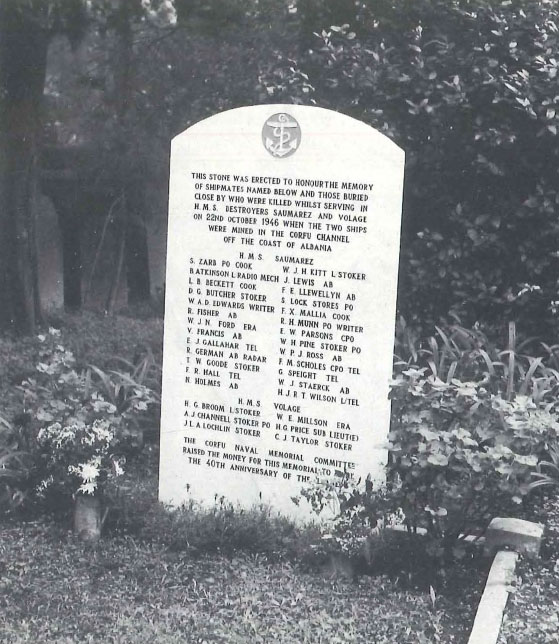

Both ships were badly crippled and only by feats of brilliant seamanship were they slowly navigated back to Corfu where they limped into the harbor in a sorry state. Forty-four sailors had lost their lives and many more were injured. The unlucky seamen were given a mass funeral with full military honors and laid to rest in the flower-strewn, old-world British cemetery in Corfu.

Apart from the dead and wounded, the two warships had been damaged beyond repair, apparently by a country which did not even possess a navy. Both the British Admiralty and the ruling Labour Government in London (which had been shilly-shallying whether to recognize Enver Hoxha’s Marxist-Leninist state or not), were outraged at the illegal mining of international waters in peacetime. They blamed Albania for what they saw as a cowardly criminal act and protested vehemently.

Albania, however, denied all knowledge of the incident or the mines and accused Britain of creating the situation to suit its own political purposes. British minesweepers, sent in once again to clear the channel, found 22 mines in all, one of them only 50 metres from the Albanian shore. As they hadn’t a barnacle or piece of clinging seaweed on them, they obviously hadn’t been long in the water. Experts testified that they had probably been laid within the two previous months.

With this damning evidence Britain took the case to the newly-founded United Nations in New York where Albania was defended by a young talented Russian diplomat, Andrei Gromyko, who had not yet begun his long career as Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union. Albania, he argued, could not have laid the mines, as at that time it possessed neither the mines themselves nor the necessary equipment to lay them. Even if Albania had not actually placed them in the water, it had certainly known about them, the British retorted. Enver Hoxha reiterated that it was all a British fabrication; British claimed compensation and satisfaction.

In the end the matter was referred to the International Court of Justice at The Hague. On a split decision (11-5) the court found against Albania and ordered it to pay almost one million pounds in compensation. Albania refused to accept the verdict, adding that in any case it did not possess the required amount as all its reserves had been looted during the war.

British had, sometime earlier, recovered some of this loot, ten million pounds worth in gold which had been appropriated by the occupying German army. The authorities in London had been waiting for a stable Albanian government to emerge out of the post-war chaos before handing it back. Now the gold was impounded and placed in a vault in the Bank of England until a settlement was reached. And there it remained until today.

honor all those killed in the incident / Photo courtesy of Captain J.J. Pearson

Many attempts had been made by parliamentary pressure groups and diplomatic circles in Britain during the intervening years to bridge the gap and re-establish at least quasi-normal relations with Tirana. Even after the Hague decision, opinions continued to vary in Britain as to the degree of Albanian guilt. The majority, which included Julian Amery a former member of Parliament and SOE officer who liaised with the Albanian partisans during the war, believed that Tito had supplied the equipment and expertise.

Others believed it was the Russians who were at that time building a naval base on the Albanian coast. There is even a possibility that the mines were Italian, left behind in their arsenal when their forces retreated. As the court remarked, “the origin of the mines is a matter of conjecture.”

But it went on to rule that whichever power had supplied the mines and requisite know-how, the narrow channel could not have been mined without the express knowledge and agreement of the Albanian authorities.

Both sides remained unyielding and as late as 1982 Hoxha was still sticking to his official story, that the incident was a British plot. Only during the political thaw which followed his death three years later, was the matter raised again in earnest.

In March this year Sali Berisha, a brilliant cardiologist turned politician who speaks fluent English and French, swept to power at the head of his pro-market Democratic Party. His victory signalled an end to the Marxist isolationism which Albania had adopted since the 1940s. At his post election celebration rally, Berisha underlined his country’s new foreign policy by saying “Hello Europe, I hope we find you well!”

Talks taking place between the British and Albanian governments, details of which have not been released, were quickly concluded and at long last the gold is returning to Tirana. Albania will, in turn, hand over an agreed sum of 1.1 million pounds in compensation for the ships and men lost in the Corfu Channel so many years ago.