A friend of mine once wrote: “The Greeks are barely Greek in summer, but in winter, they again pull out their komboloi, throw out all those tacky, unsold cat-calendars, and try to find the plumber.”

When I first decided to move to Hydra last October, friends and family were aghast.

“You’re moving to Hydra for the winter?”, they exclaimed.

“What’s there to do?”

“I hope not much,” I replied.

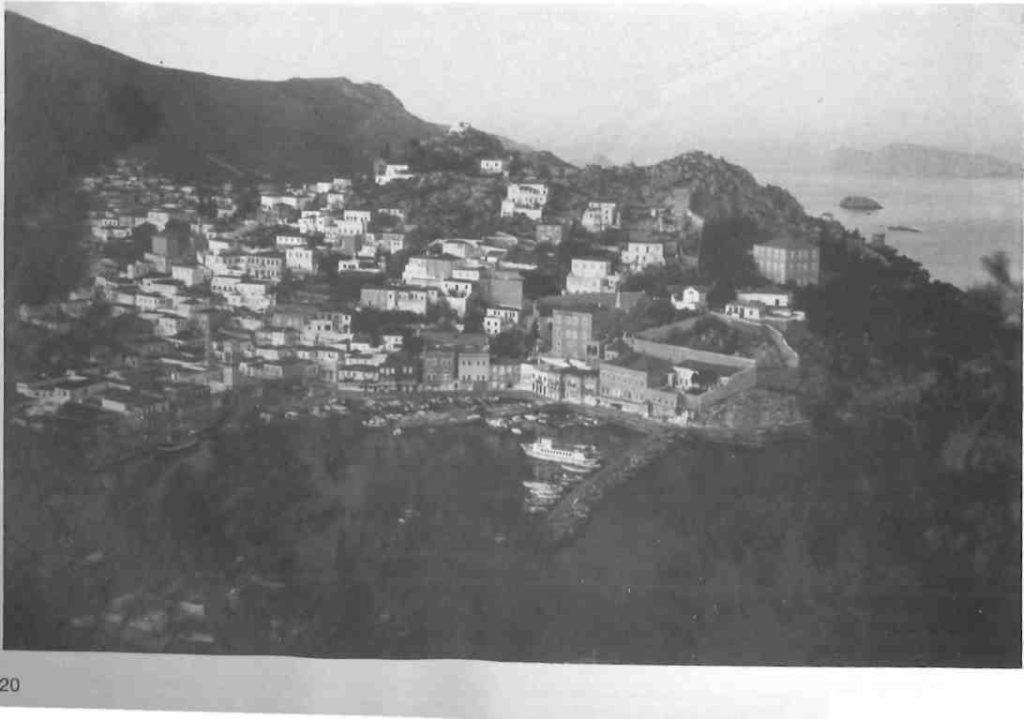

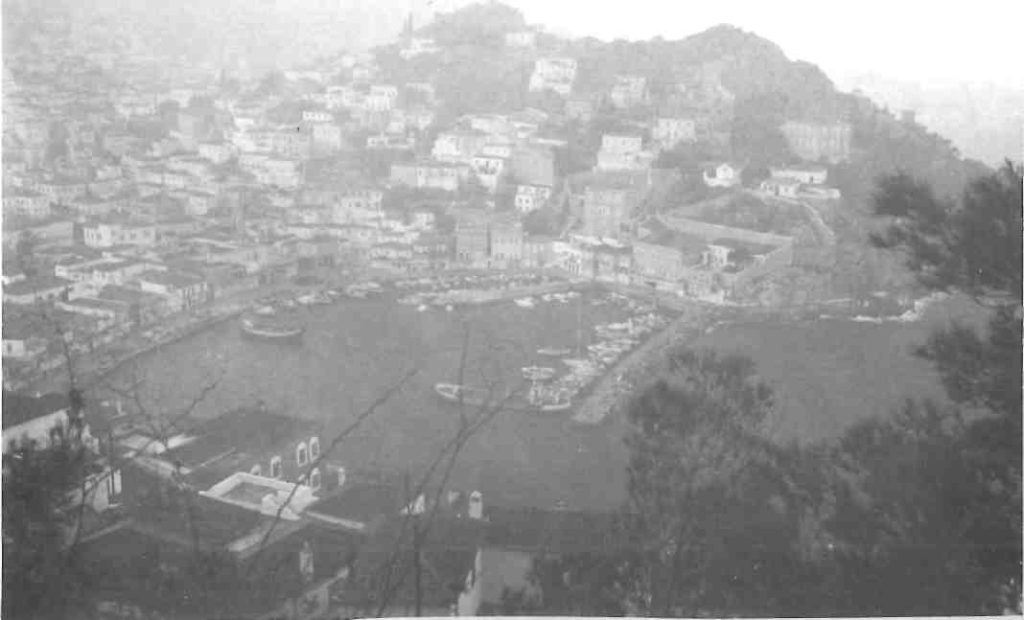

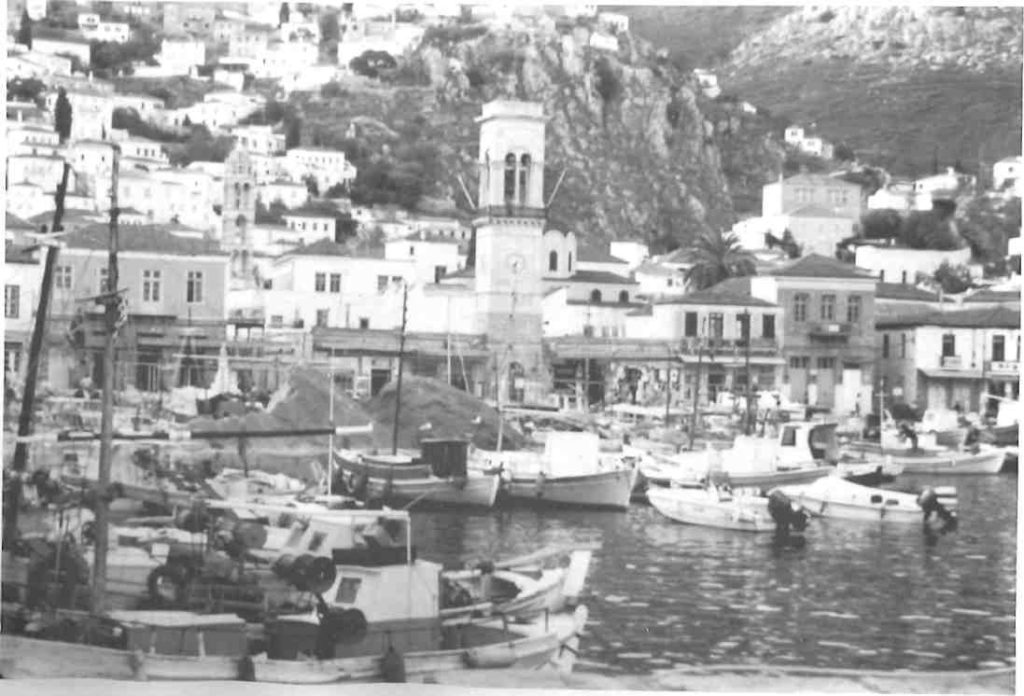

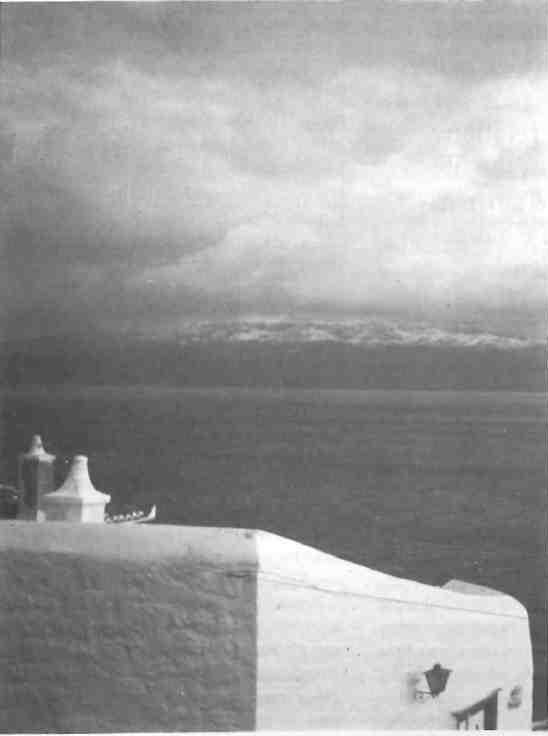

I planned to read, write, take photographs, paint and generally contemplate life in the cold, quiet, empty port under an often dramatic winter sky. Indeed, Hydra was at times in winter more like an abandoned movie set than an actual town; wet, empty, and eerily overlit by bare bulbs swinging in the wind with a somberly surreal Christmas tree barely standing, off to one side. It is not surprising, then, to learn that Hydra’s contemporary popularity as a retreat for ‘creative intellectuals’ stems from her discovery in the late 1950s as a location for filmmaking like Boy on a Dolphin and Phaedra.

Now that Hydra is back under the relentless haze of a hot summer sun, and the patronizing gaze of tourists -well beyond that beautiful winter light, that coldest snowiest season in Greece in 50 years- I recall my 1991 winter exile on Hydra with some fascination. The company and combination of native Hydriots, along with expatriate painters, writers, construction workers, and various world-weary ‘idlers’ like myself often proved as stimulating and bracing as the weather. Gathered together against the cold in one of the few tiny tavernas that stay open all year, we sang, danced, drank, ate together – but above all, philosophized about life, love, the island, the weather, indeed any subject that rated group-discussion – and some that didn’t. Hydra in the winter, I learned, was the world in microcosm.

Come summer, she overcompensates, opening her arms indiscriminately to thousands of day-trippers from around the globe. From April through September, no fewer than three tourist boats and three ferry boats arrive daily; two other cruise boats arrive weekly; and Flying Dolphins ply the harbor hourly from sunrise to sunset, turning Hydra into yet another suburb of Athens.

In the winter, there is no indication of this approaching circus. In nearly all kinds of weather, all winter long, one excursion boat would arrive daily – a blessing for the local shopkeepers – and disgorge its close-bundled cargo of mostly Japanese, Hong Kong Chinese tourists, apparently when most of them take their holidays. With admirable efficiency, they would fully utilize their brief hour on the island feeding the cats, lunching on kalamarakia, pricing gold and taking countless snapshots. Watching them was the ‘high point’ of some short but dull winter afternoons.

Less regular, but certainly as welcome, were the evenings Thanassis came down from the hills to play beautiful bouzouki or guitar music behind closed shutters in one of the port cafes – a privilege solely for the ears of winter idlers. Through spring and summer, Thanassis is too busy driving one of the local construction trucks to sing and play.

Hydra’s history has long been a welcoming one, though the reasons may not be readily apparent. Its shores have long been considered ‘inhospitable’ to maritime traffic – with the stunning exception of the deep, natural amphitheatre of its harbor and port-town. It is largely rocky and devoid of vegetation – though wheat, olives, grapes, and most notably almonds are still grown here. It is termed ‘claustrophobic’ and ‘lacking decent beaches’ in several tour books – and if that is what they want to continue to believe, it is fine with me.

Hydra has always been short of water – even before the influx of summer tourists. Oddly enough, Hydrea, as first mentioned by Herodotus in the fifth century BC,has at least been historically perceived as a place to draw water. But even the island’s famous Kala Pigadia (Good Wells), first dug in 1800, could not sustain inhabitants year-round. Then, as today, water had to be carried over from the Peloponnese, in spite of the efforts of a Turkish diviner to find further sources of water on the island.

Today, Hydra’s popularity is no less of a paradox as she draws her own particular mix of immigrants, both ‘typically’ Greek and ‘untypically’ foreign. Painters and photographers come for the light and respite; would-be writers come to hole-up and, it is hoped, write. Native Hydriots go about their business with unaffected charm; and the creative, curious, rich, poor, and/or merely retired come for a much-desired break from the ‘real’ world. It all makes for a heady blend at times, particularly when congregated in our indoor winter closeness.

On one end of the spectrum, there are those residents who theorize as to the island’s innate ‘energy field’, allow-ing visitors to ‘recharge’ naturally with time. On the other, there is the down-to-earth banter of the local donkey-men, leading their charges loaded down with everything from bricks to champagne – up the steeply-winding paths from the port, for there are no cars or motorbikes on Hydra, just a handful of garbage and construction trucks. Add to this Hydra’s proximity to Athens – just over an hour by hydrofoil in most weather – and for Athenians looking to escape the din and pollution of the city its attraction is unparalleled.

“I fell in love with it the day I arrived,” exclaims Bill Cuniiffe, an ‘ex-pat’ resident of nearly 30 years. “The winters remain blessedly unchanged, but of course more and more tourists are arriving every summer. Hydra is becoming just another tube-stop. Years ago there were no excursion boats, just the occasional ferry boat, and it seemed the whole island would congregate to see who would get off.”

Obviously, tourism, television, and the Flying Dolphins have brought wealth and world-sophistication to the island, but at what cost? It seems more boats equal more paradox. All winter long, an older Greek fisherman here lamented: “The young people used to come down to the port to sing, drink, dance. Now they all sit home and watch football on television. I realize that Hydra must change along with the rest of the world, but why must all the joyful customs be lost first?”

If nostalgia is not what it used to be, neither is Hydra. ‘Ί could name-drop for at least three days,” claims Cuniiffe with a smile. In 1973, he opened the now-defunct, but once world-famous stop on the yacht-route known simply, infamously, as Bill’s Bar.

Town and Country called it “the most important watering-hole for the alcoholic jet-set.” Melina Mercouri, with husband Jules Dassin, declared it her favorite bar as she rubbed shoulders with notables like John Cleese (of Monty Python fame), Bill Buckley (of rolling-eyed notoriety), and Joan Collins (a great poker-player, by the way). “And of course,” adds Bill, “Onassis and Jackie would drop in from time to time.”

There was likewise a lot of warm, glowing recollection of Lulu’s past, an old taverna still open here after 20-odd years. Tales of Greeks dancing with tables in their teeth, retsina and ouzo flowing freely, filled our winter evenings. Indeed, Lulu’s is still open, the company and conversation still lively, at times the food still fairly fabulous. But the locals have been replaced by sunburnt tourists; and the sweet wail of rembetika in the winter has been ousted by the sombre blue glow and the noisy commercials of a large, imposing television set.

Has success completely spoiled Hydra? Yes and No. Now that summer is in full swing, Euro-music blaring from the local disco competes with the braying of donkeys well into the early-morning hours. Yet, at least two bars here still defiantly play only Greek music, and they are popular with young Greeks and foreigners alike. A frontistirio first opened by Cunliffe’s wife Lena in the early 1980s is still going strong, with 130 students of all ages aiming at proficiency. And in spite of its transient summer nature, Hydra remains virtually free of crime, a safe place to raise a family, and a place where the elsewhere vanishing concept of community still has a meaning.

Beyond this, the island maintains a certain 19th-century integrity and character through the conscious preservation efforts of local leaders and residents. Strict building controls are enforced, and the introduction of motor vehicles has long been opposed. Where else in Greece can one completely escape those prevalent, deafening motorbikes?

Firm in place on a Council of Europe list of protected monuments, Hydra also evokes the past with the imposing presence of a surviving handful of slope-roofed mansions both lining the port and dotting the hillsides. Here is evidence that current commercial trends on Hydra are not without precedent, for these homes were built by wealthy shipowners who imported their own architects from Genoa and Venice. So today’s travellers to the island all have something in common with Hydra’s past. They are but the latest wave in a broad historical ocean of immigrants. Why do they keep coming?

“To paint,” explains Bill Pownall who, along with his wife Francesca, has been a permanent resident since 1975. “Hydra had everything to do with my wanting to paint. I first arrived here from Australia in the mid-1960s, having been a musician and in advertising. The people I met here welcomed me, gave me encouragement, a sense of community.”

Hydra as a community is a concept not immediately evident to the visiting boatloads of summer tourists. “This is a very social island,” Pownall observes. “Sometimes (especially in the summer), you meet more people than you can handle. But in the winter, there is still contentment and peace-time to remain open to that creative frame of mind.” And as for that sense of community, Francesca, a poet, adds: “The Greeks here especially are ‘classless’, which is not to say that money isn’t important to them. But if they like you, it doesn’t make the slightest difference how much money you have. They will rally round you, help you find a house, and so on.”

Karin Craze and Anita Thomas are two women I met this winter who are also putting this concept ot community into practice. They own a shop designed primarily with local residents in mind, something of an anomaly on such a ‘touristy’ island. Open all year – and cleverly called Ti Em1 Afto? (What Is It?) – they sell a combination of home furnishings, rugs, antiques, glassware and gifts that give credence to a certain Greek appreciation for sophistication. “We opened a year and a half ago with the very idea of giving something back to the island,” Karin asserts. “Greeks are very ‘house-proud’, and because our prices are comparable to those in Athens, we save the locals an often-dreaded trip to the city. Our first winter was a bit rough, but now we are enjoying the full support of the Greek community here.”

Swiss-born, Anita adds: “And we’ve now opened a long-overdue – and very popular – book-exchange service for the foreign community and Greeks alike.”

This summer we are all still here, albeit more in-hiding from the visiting hordes. Sometimes I sit with the Greek fisherman who, all winter long, lamented the advent of television.

“There are two kinds of people who come to this island,” he asserts, as we watch the endless parade of people along the port, “those who merely take what they want, and, those who give something back.” I feel fortunate to have ‘wintered’ with some of Hydra’s contributors, a fascinating and caring array of people who ‘stay’.

Now, may we have ‘our’ empty movie-set back?