India has always been a magnet of attraction; a goal for fulfillment or conquest. After his subjection of Persia, Alexander the Great was lured east as far as the Punjab which the Greeks called Pentapolis. Later, Mongols were attracted south and established there an empire that lasted for over two centuries. India, as all know, became the jewel in the crown of the empire which took its place, and Queen Victoria was very proud to bear the title ‘Empress of India’.

I, too, fell under its spell when I came to know something of an ancestor of my husband’s, the famous but elusive Demetrios Galanos who spent much of his life in India and died there in 1833.

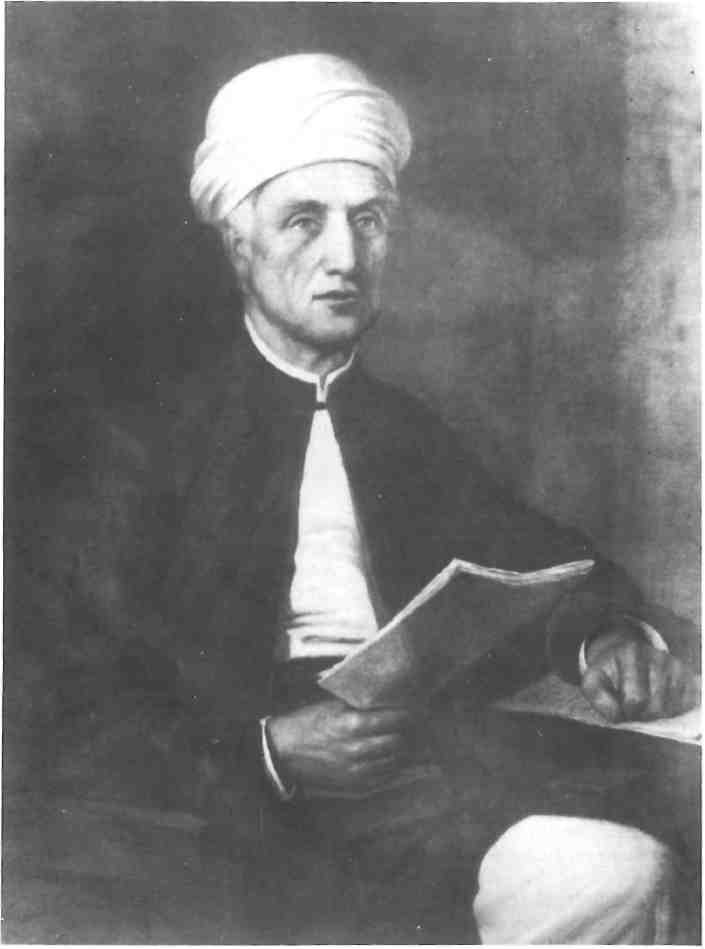

Galanos ‘the Athenian’, as he was widely known, came from one of Athens oldest families. He was born there in 1760. In his early youth he already showed promise as a scholar having gained a thorough knowledge of the Greek classical authors by the time he was 12. Destined for the priesthood, he studied first with the famous teacher Panayiotis Palamas in Messolonghi, then at the Theological School on Patmos. At the invitation of his uncle Gregorios, Bishop of Caesarea, he studied another six years in Constantinople.

It happened at this time that a growing number of Greek merchants there were finding employment with the rapidly expanding British East India Company. Contacts with them led Galanos out to India to teach their children in Greek communities which had sprouted up in Dacca and Calcutta.

Galanos soon mastered Sanskrit, as well as other oriental languages and dialects and was introduced to Hindu philosophy by Brahmans. On retiring from teaching, he moved to the holy city of Benares, devoting himself to translating the Hindu epics and philosophical works into Greek. He died in 1833 and was said to be buried in the British cemetery there. In his will he bequeathed 36,000 drachmas to the University of Athens along with his books, manuscripts and translations which were published in the 1840s and 50s. The MSS are now in the National Library.

‘Going native’ was very unusual at the time, and thought quite strange, but Galanos’ studies were just as original and ground-breaking, earning him the title ‘Plato of the East’. In a biography of the Indianist, Siegfried Schulz of the Catholic University of America, Washington DC, has composed a vivid portrait of Galanos, finding both his ethnological and linguistic work way ahead of their time. As an intellectual link between eastern and western civilizations he appears in his global thinking to be very up-to-date.

Some time ago my husband and I visited Benares to see if we could locate our forebear’s grave, for only hearsay had placed it in the British cemetery where it had never been seen. Such a jungle of unpruned vegetation confronted us in the cemetery that the 19th century tombs could scarcely be made out. It seemed a fruitless task, involving months even, if indeed the grave was there at all. But we persevered, following a path, my husband exploring the thickets on one side and I on the other. Yet, within five minutes, as if attracted by a mysterious force, pushing aside some tangled growth just below the cemetery wall, I was confronted by Galanos’ weed-choked gravestone. Beneath the dirt emerged the letters ‘Demetrios Galanos, the Athenian’…

The day we set out, the steps leading down to the Ganges, source of life, were filled with the faithful, the sky pink-violet at the break of day, the palaces of the maharajas empty and ghastly. By the sides of the Ganges, on both banks, the bonfires are burning the dead. The Sacred River receives the ashes to bear them away, for, according to the Hindus, death is not an ending but the passage to another life.