The first time I saw Chlemoutsi, I didn’t even realize it was a castle. I was a bride, then, fresh from America, following my husband, as the John Denver song goes, “Up and down, all around…”

We were searching for a mountain village where he could serve out his compulsory year as a Rural Doctor.

We had narrowed the long list of available villages down to those situated in the nomos of Ilias, a region in the western Peloponnese facing the Ionian Sea. It is exceptionally beautiful even by Greek standards. Its plains are fertile and green; its mountains craggy and mystic; its seaside, whether rocky or sandy, always sparkle and invite.

Oh, I lost track how many times we drove up and down the main road between Pyrgos and Patras but every time we did, my eyes would be oddly drawn to a certain cream-colored hill, about ten kilometres to the west. It looked rather like a turtle lumbering across the coastal plain through a bed of vegetation. The olives and fruit trees growing in patches on the slopes of the hill give it the checkered look of authentic tortoise-shell.

We visited so many villages in out of the way places that seemed to me lost in the Middle Ages, that every time we caught sight of ‘turtle hill’, I always breathed a little easier. It meant we were approaching paved roads, petrol stations, civilization! The 20th century was near at hand!

Then, as the days went by, I noticed that when the light from the sun reflected against the sea and the land in a certain way, something seemed to be sitting on the summit. A village? Whatever sat on the turtle’s back, it didn’t have a configuration like any village we had seen so far. Finally I asked my husband about it.

“I think it’s called Chlemoutsi,” he said nonchalantly, looking up over the steering wheel.

“It’s a Frankish castle.”

“A Frankish what?” I exclaimed.

“Greece has Frankish castles?”

Suddenly, the tales of King Arthur and Lancelot and Guenevere and Camelot and Richard The Lionhearted and the Black Prince and Ivanhoe and Rowena and The Talisman all bounced through that cultural grabbag, my North American head.

“My darling wife,” he chuckled,

“Are you to be counted among those who never learned that Greece is more than just her ancient history?”

My husband called it Chlemoutsi, but I soon discovered a multitude of names that referred to the same place. It was the beginning of my education.

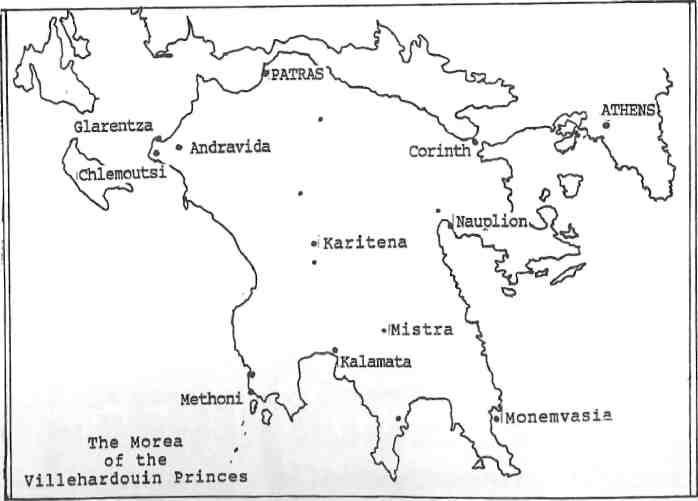

Chlemoutsi, Klemoutsi, Clermont, Clarmont, Chateau Tournois, or Castel Tornese. They all referred to the same great mass of carefully-laid stones on the hilltop, whereas Chiarent, Clauntza, Clarence, and Glarentza all referred to another fortress on the seaside four kilometres to the north, today known as Kyllini.

Chlemoutis, I found, is the name of the hill, on which the great castle sits. Derived from Chelonatasit is a corruption of the ancient word cheloni, which I discovered to my delight, means tortoise.

So I was not so ignorant after all, and what my brothers and sisters saw three millennia ago, I had noted, too.

‘Clermont’ was the name the Franks gave it, and ‘Chateau Tournois’ was often used after it was granted, at the time of William II de Villehardouin, Prince of Achaia, the right to mint the widely circulated coin struck at Tours called tournois or tornesi. (Opinion differs as to whether the actual mint was located here or at nearby Kyllini.) ‘Castel Tornese’ became its name during the Venetian occupation.

Chlemoutsi is one of the best examples of Frankish fortification found in Greece. Its origins, like so many of the local romantic remains of the Middle Ages, emerge from very unromantic facts, mostly as the sordid results of the infamous Fourth Crusade. This motley army, led mostly by petty, greedy impecunious Frankish knights, was transported and advised by astute Venetians who had other things on their minds than rescuing the Holy Sepulcre from the infidel – namely, booty.

As a result, the Soldiers of Christ were diverted from their sacred task and instead plundered the greatest city in Christendom, Constantinople. This accomplished, they established the Latin Empire of the East and carved it up into fiefs.

On hearing the news of the pillage of Byzantium by his countrymen, an ambitious knight, Geoffrey de Villehardouin, while on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, decided to try out his luck in the Morea. Earlier, he had been forced by a winter storm to take refuge in Methoni and concluded the natives of the Morea were both rich and un-warlike.

His’ uncle and namesake, Geoffrey de Villehardouin, recorded in his famous chronicle of the Fourth Crusade the words spoken by his nephew that so aptly portray Geoffrey’s yearning to conquer the land and become much than a mere knight. To his liege-lord, William de Champlitte, who was laying siege to Nauplia he said, “Sir, I come from a rich country called the Morea; take as many followers as you can command, and leave the camp; and by God’s grace we will go and conquer that country.”

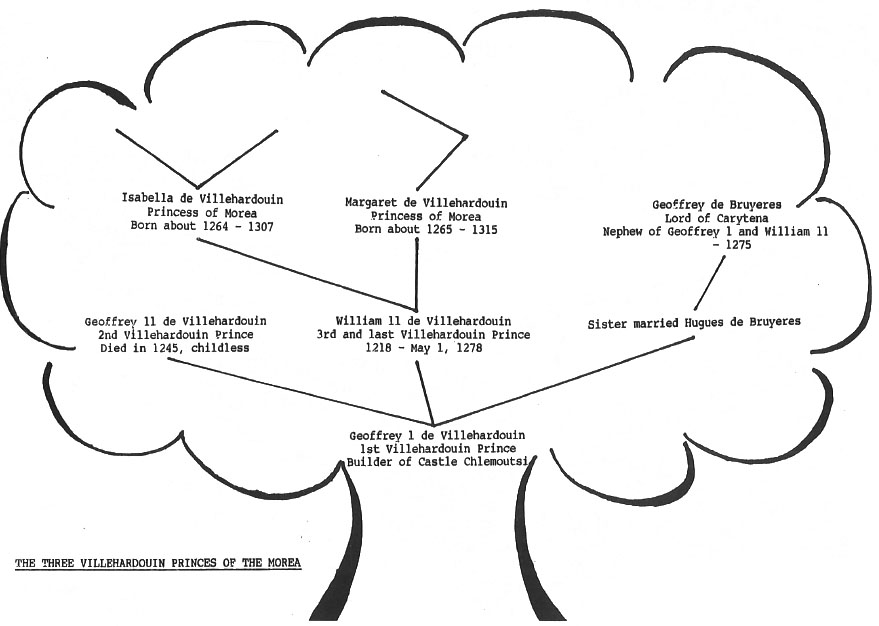

This they did, and after the death of William de Champlitte in 1209, Geoffrey I, banking on his popularity with chronicled ability as a leader, and political cunning, had himself referred to in letters written by Pope Innocent III in 1210 as ‘Prince of Achaia’. (During the 13th century, the geographical names Achaia and Morea were used interchangeably.) It is to this Prince that the walls of Chlemoutsi most likely owe their construction.

The most detailed work extant on this period of Greek history is the Chronicle of th e Morea. Written around 1300, it has, however, several drawbacks. First, it is prejudicial against the Greeks in the extreme; secondly, its combination of fact and fiction needs careful sifting in order to be of use as a historical work.

The Chronicle of the Morea attributes the building of the castle to Geoffrey II, not his father. Antiquarian H.F. Tozer in the last century and historian William Miller (1908) agree. The Blue Guide to Greece generously attributes the building of the castle to Geoffrey I (p.358) and Geoffrey II (p.22).

It is all a question of who carried on the dispute with Rome between 1220-23, the years of Chlemoutsi’s construction, and confiscated funds from the Latin Church upon refusal of the clergy to contribute anything toward the defense of the Morea. These funds were the revenues by which the walls of Chlemoutsi were erected.

The late Kevin Andrews, in his Castles of the Morea (1953), indicates that the builder had to be Geoffrey I, quite simply by the wording of Pope Honorius Ill’s excommunication order. “G. Prince of Achaea, G. his son, and his vassals.” And again in 1223, when Geoffrey was reinstated into the church, “G. de Villehardouin, Prince of Achaea, his wife and his sons, his land, and all his possessions.” This could only refer to Geoffrey I because all sources agree that Geoffrey II de Villehardouin died childless in about 1245.

So the castle was built, a watch tower and fortress palace, with a panoramic view of islands, sea, mountains, and plains. It completed the third point of a triangle with the inland capital, Andravida (Andreville), and the port, Glarentza. It was a thriving and populous region where French was said to have been spoken with a purity equal to that of Paris. Frankish Morea became a haven for the younger sons of the French nobility.

Glarentza became so important that Boccaccio in the 14th century used it as the setting for one of his best stories, and, conjecture has it that the English title “Duke of Clarence” derived from this town after a great granddaughter of Geoffrey I married Edward III.

So, according to Shakespeare, when Richard III had brother Clarence thrown into a malmsey-butt, an originally Greek title mingled intimately with an originally Greek wine (monemvasia).

The last time I visited Chlemoutsi was on a hot day last August when the temperature was reaching toward 39 degrees Celsius. The drive from Andravida, where my family and I had walked through the weeds and among the rusty swings and seesaws of a neglected paidiki hara to inspect the remains of the Frankish Gothic church of Saint Sophia, was an enchanting journey through cicada serenaded olive groves which granted us occasional, peek-a-boo views of the castle.

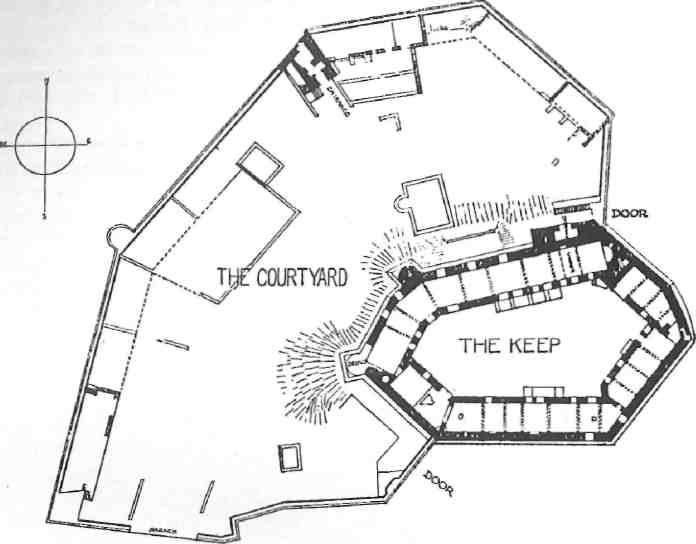

The east curtain wall, which also combined as the east wall of the irregular hexagonal keep, and is the focal point of the hilltop fortress, first greeted our eyes. The wall here is nearly 20 metres in height. Together with the steeply dropping land, it shows off Chlemoutsi’s pre-artillery age defensive capabilities to perfection.

Meandering first through the quaint, flower-scented lanes of the village of Kastro, one is even more immediately struck by the grandeur of Chlemoutsi. Not only is it immense and its scale imposing, with curtain walls measuring close to 200 metres north to south, but its bearing is regal. It imparts to even the most casual of visitors a sense of terrible dignity. Instinctively, one knows that this old warrior of a castle was the focal point of a noble domain; obvious, too, that Geoffrey I put much of his own personal yearning and hope for his new principate into the building of this castle.

Most of what we see today is of the original design, so the stamp of the Franks rest strongly and quite beautifully upon it. The walls, made of rough-cut, well-fitted limestone, dwarfs us, awes us, so massive and rugged that we wondered at the might of medieval man to raise them.

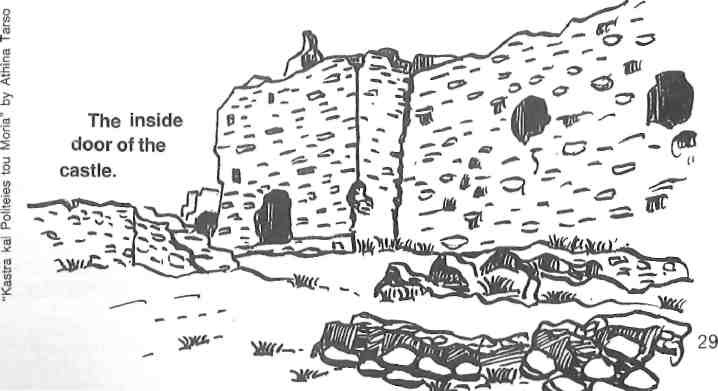

The entrance gate is huge. Facing the sea on the northwest side, it is like the yawning mouth in a surrealistic painting. Today, it stood open and welcoming, with no teeth-like portcullis drawn or all set to drop down on unsuspecting heads. (Prospective visitors: Please note, however, that a 1980s iron gate will shut you out on Mondays and holidays.)

The original Frankish pylon was added onto by the Turks who made the gate a part of an unbroken front to the curtain wall. Buttresses springing out at its base further strengthened it.

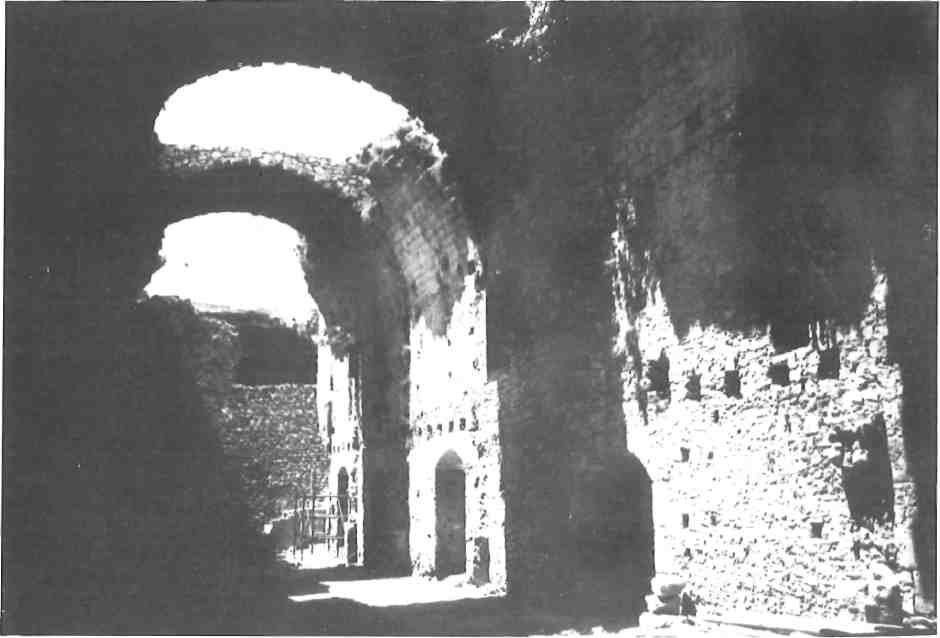

We left the bright, unrelenting sun and entered into the welcoming dark depth of the wall and were refreshed by the coolness of its chamber. A Turkish dome hangs immediately overhead, followed by an archway, an opening to the blue sky, and finally another archway, giving the additions and different architectural styles of the gateway as a whole interest and variety.

From the outer bailey the vast courtyard, choked in wildflowers, is the size of several football fields. Looking across its intricate foundations and ruins, to the walls of the inner redoubt, one sees Chlemoutsi as a castle within a castle.

To the left of the gateway is a well-preserved building that dates from the early 13th century and measures ten by 35 metres. The curtain walls form its north wall and three lancet windows and a fireplace break up its length.

Climbing further, to where the curtain on the east side joins the hexagonal walls of the keep on the summit of the hill, one reaches the entrance to the inner bailey. Like the main gate, it is refreshingly cool and impressive. Rising 20 metres and spreading almost as wide, it projects from the keep’s walls by five metres. One marvels at a work still capable of supporting the weight of several tons of stone above one’s head 770 years after it was completed.

The gate leads directly into one of the keep’s six huge galleries before opening up into an inner courtyard. This space is a lovely, congested array of walks, stairs and ruins. The steep gallery walls that face the inner yard are pierced with numerous arched windows. They must have been constructed with the intent of letting in much healthy, Greek sunshine and air into the conqueror’s chambers who, coming from a northern land, must have greatly loved and appreciated its warmth.

To the left of the gate, stairs lead to the roof above the vaulted chambers. Though the hill on which the castle sits is relatively low, its view is uninterrupted for many kilometres around. To the east, clearly seen, is Andravida, once the thriving capital of the Morea, now a sleepy agricultural town. To the north, a cruise ship slips out of Kyllini harbor. During Frankish times it would have been a merchant ship or a galley sailing from Glarentza. To the south, one can see Cape Katakolo with its Pondikokastro, once the summer residence of the Villehardouins. To the west, the sea floats out to the horizon, linking Frankish Morea with the nations of the west.

The sudden sound of a supersonic Phantom jet screeching low over the ramparts from the military base close by breaks the contemplation of this medieval scene with the poignant realization of how flimsy the stone castle is today. Hi-tech makes the giant castle on the hill seem like little more than a child’s ‘Lego’ land. As quickly as the plane appeared, it is gone, leaving in its wake a vague feeling that something is out of order. After a moment of silence, the cicadas start to sing, and bees to drone again.

The walls of the huge galleries that circumvent the keep still stand, as well as much of the roof. Restoration is in progress with workmen and their tools scattered throughout the grounds. It is a welcomed sight: Chlemoutsi is being preserved.

As I walked out of the keep, the arch that had impressed me with its sturdiness when I entered, now caught my breath as I left, for it framed most beautifully the land and sea view to the west. I wondered if, perhaps, Geoffrey I had purposely had this arched gateway constructed in this way so as to be reminded of his home, across the sea, in far-off France.

Looking back towards the lofty, vaulted gallery behind me, with its fire-places and windows still clearly visible, I couldn’t help wondering just who had lived among these walls.

The three Villehardouin princes, whose realm was one of the strongest and richest in those days, had all felt that building and then holding Chlemoutsi could insure the Morea for them and their descendants forever. Standing among these massive walls one easily understands why. But, as always, conditions change – and rapidly in this case. Prince William’s second and most beloved daughter, Marguerite died a political prisoner here in the very castle that her grandfather had built.

As I walked freely out of the castle’s walls, which seemed to whisper its story in the wind, I remembered the words that Geoffrey I had said to William of Champlitte at the start of his Morea campaign in 1205, and I couldn’t help feeling that he didn’t understand “the grace of God” and had pushed God’s hand to fulfill his own will. For history here proves that it was God’s grace to hear the prayers of the Greek people and see that their land eventually re-joined the culture and the faith which they had never abandoned.

In 1427, Chlemoutsi passed into the hands of the last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos. In so doing, the last foothold of the Franks in the Morea was lost. The Franks who remained, were assimilated into Hellenism which is always ready to welcome newcomers.

Finally, in 1825, after years of Turkish, Venetian, and once again Turkish rule, the heroes of independence wrested Chlemoutsi from the arms of Ibrahim Pasha and it passed back to its rightful owners.

As for the three mighty Villehardouin princes, they now lay side by side, father and sons, in an unmarked, all but forgotten grave in Andravida.

But the castle remains, a silent reminder of another age overlooking a sweet, rural area of Greece. Very quickly, it plunges everyone who comes by here into another state of mind. The smell of herbs and flowers that waft over the hillside; the seabreezes that float upward from below, and the winds that tease around the old stone walls, bring a fairytale to life transforming, all of a sudden, 20th-century visitors into princes and princesses of the Morea looking out at the world from Cloudless Mountain.