The Greekness of Crete is not at issue just now, despite a certain foreign leader’s recent comment about the Turkishness of the island. If debate arises (controversy about the EC price for their olive oil permitting), Cretans can be guaranteed to make much of their Minoan roots in the land, reaching back two millennia earlier than the Macedonians can claim in theirs.

Cretan patriots meanwhile might spare a thought this month for an exiled Minoan who looks to be spending the centennial of his residence abroad unsung in either his adopted or native land.

The Master of the Animals, as he is known in the select academic circles where he is now confined, deserves at least a commemorative postcard, if not solid gold replicas made in his image and likeness like his close relations, the famous bees of Mallia.

The nature god, as he is also described, is a pendant which is part of a “rich, beautiful and perplexing collection of ancient jewellery and goldplate” offered for sale to the British Museum in 1891.

The perplexity is the consequence of a commonly accepted story that the collection was found in a Mycenaean tomb on Aegina and was the cache of tomb robbers in ancient times, perhaps in the late 12th century BC, when law and order was breaking down as invaders from the north swept down and settled in much of Greece.

‘Richness and beauty’ prevailed over mere ‘perplexity’, and the museum authorities are said to have agreed that the treasure was in some respects of greater importance than that found 16 years earlier at Mycenae by Heinrich and Sophia Schliemann. “The workmanship is more advanced and the signs of indebtedness to Egypt and Assyria more conspicuous,” said A.S. Murray, then keeper of Greek and Roman antiquities.

“Like the antiquities at Mycenae,” the scholar went on, “this new treasure belongs to an early age of civilization when the Greeks were being greatly influenced by the older nations of Egypt and Assyria through the medium of the Phoenicians.”

Museum Trustees accepted Murray’s recommendation and went ahead with the acquisition. On May 14, 1892 the director reported to the trustees that 4000 pounds had been paid to the leading Aegina sponge merchants, Messrs Cresswell of Camden Town, though at the time the vendor, price and alleged find-spot were not divulged. Details of the transaction may be checked in the museum records.

‘Minoan’ civilization was then, of course, unknown. Crete was still part of the Ottoman Empire (till 1898). Arthur Evans, whose finds inspired him to dub a new civilization with the name of Crete’s great mythical King, had not begun hisexcavations at Knossos. But, as keeper of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, Sir Arthur published the first scholarly assessment of the Aegina treasure trove in the Journal of Hellenic Studies of 1892-3: “It must be a matter for rejoicing that our national collection should have received so important an accession,” he wrote. Never mind he dated the works about 1000 years too late. Interestingly, he seems to be one of the few scholars in the century to have raised the question of the justice of the acquisition.

“Opinion may well differ as to the propriety of removing from the soil on which they are found, and to which they naturally belong, the greater monuments of classical antiquity,” he wrote.

objects, only pottery.

Ironically for this highminded view, the story that now seems most probable is that the sons of the soil themselves flogged off the treasure.

If little else is sure, what is uncontrovertible a century later is that the little nature god and his companion pieces comprise a valuable heritage from the Minoan golden age. The works date from the time “Cretan jewellery was at its finest, when Minoan wealth was at its zenith,” enthuses Lucilla Burn, a curator of Greek and Roman antiquities at the British Museum, in a book published by the museum last year.

The treasure “is astonishing in both extent and quality… and displays all the virtuosity of Cretan goldsmiths, skilled in working sheet metal over moulds, linking tiny loops of fine gold chain or rolling gold wire.”

Detailed analysis of the works was done by a specialist in Mycenaean shaft graves, Charles Gates, for a history of ancient Greek art and architecture edited by Professor Robert Laffineur and published by the University of Liege.

Belgian archaeologists work with the French who are in charge of excavations at the Minoan palace at Mallia and its adjacent royal communal cemetery. Amongst locals it is known as ‘Gold Pit’ (Chrysolakkos) from the amount of gold bits and pieces found there in the 1880s.

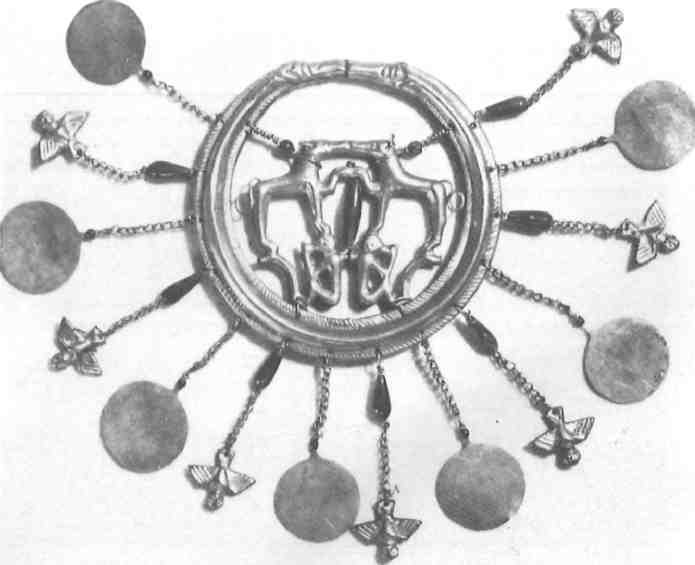

back-to-back monkeys and 14 dandling pendants (British Museum).

Like Lucilla Burn, Gates detects Egyptian and Syrian features blended with better known local characteristics. Just as the use of gold in the Mycenae shaft graves finds, especially the gold masks, suggests that early Mycenaeans had borrowed from Egyptian ideology, so too does it seem of these Minoan works, he wrote three years ago.

Gold was the symbol of status and its religious significance associated with the sun and the sun god in Egypt. The use, too, of cornelian, lapis lazuli, mined with difficulty in Afghanistan, and – in smaller amounts – jasper, amethyst and rock crystal, also shows that artisans were aiming at creating objects of prestige.

Gates concludes the collection was “created at a time society was at the crossroads in mainland Greece in the middle of the second millennium BC (1700-1500). The elite needed a new art to underline their status; their artisans searched in distant lands for models; and in this new synthesis, Mycenaean art was born.”

As to the main pieces with figural scenes, he says: “Most scholars have been content to dip their toes into the water, offer a description and a tenuous guess as to meaning and leave it at that.”

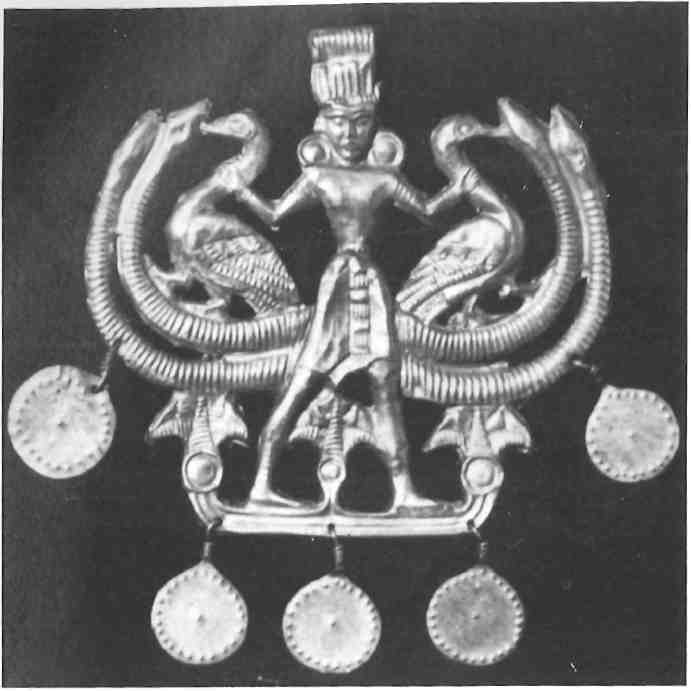

The centrepiece of the collection is the gold Master of Animals pendant, a wasp-waisted figure wearing a feathered headdress (“an abstracted version of the crown of Osiris,” says Gates), a skirt (perhaps Egyptian, but it could be Minoan, too), and huge earrings. Grandly, he is holding aloft a goose in each hand, framed in two pairs of cobras (the Egyptian symbol of royalty) and posed on a ‘field1 of three lotuses. Like the rest of the collection, the pendant is of 23 carat gold, easy to work and of good color. It may have been acquired in Egypt or Syria in exchange for olive oil, timber, wood or pottery.

A widely circulated account has made it seem necessary to accept that the treasure was found in Aegina. This has emanated from Dr Reynold Higgins, assistant keeper of Greek and Roman antiquities at the British Museum till retirement in 1977, and known for his pre-breakfast lectures on Swan Hellenic cruises.

Pausanias is our earliest source for the tradition that links Crete with Aegina, noting that the Temple of Aphaia was dedicated to a goddess known in Crete as Diktynna or Britomartis, perhaps a companion of Artemis. Would not Cretan dedication imply Cretan worshippers?

Corroboration for the Cretan presence in Aegina has come from the German archaeologist, Dr Gabriel Welter, who dug on the island from 1926-40. Islanders told him the treasure in the British Museum was found roughly buried in a hole in the corner of a rifled tomb on Windmill Hill,north of Aegina town.

As Welter deduced the presence of Cretan potters as early as 1900 BC, so why not goldsmiths? Further work in the last 20 years by the German Archaeological Institute under Professor Hans Walter has strengthened this view.

Cretan archaeologists, nevertheless, staunchly believe it is just too much of a coincidence that Cretan villagers were notoriously digging up gold treasure at Mallia at just the time the so-called Aegina treasure surfaced.

“The most plausible explanation is that the pieces came fromChrysolakkos at Mallia,” says George Rethemiotakis, curator at the Herakleion Museum. “But this is just conjecture.”

Gates accepted the view that the pieces were “deposited as grave gifts in a burial somewhere in Aegina.” The complete absence of any other gold-ware in the many ancient graves excavated on Aegina seems to cast doubt on this. When first lecturing on the topic in London in 1956, Professor Higgins suggested the pieces had been acquired in Crete by sponge divers fi ΌΓΠ Aegina. He noted that French archaeologists working at Mallia had found parallels in discoveries there with unusual characteristics of the pieces in the Aegina treasure.

Over the years, he ditched belief in the Mallia provenance because of the strong evidence for Cretan presence in Aegina and the faith he had in accounts of the discovery of the cache on the island.

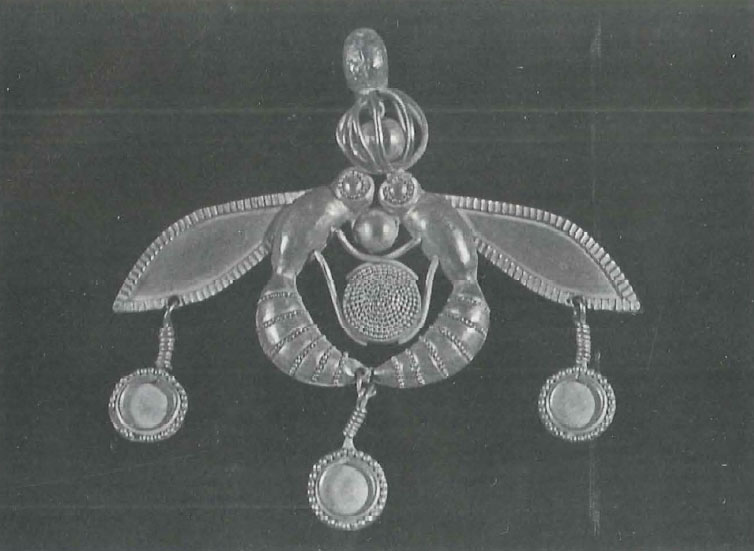

The High Minoan artefact most closely resembling the Master of the Animals is the bee pendant from Mallia. A pair of gold bees, both sharing a globular crown and, some believe, a drop of honey, have one set of wings. The ornament is more than 5 cms from wingtip to wingtip and weights just 5 grams.

If the Master of the Animals is lost and ignored in the vast collections behind the Corinthian colonnaded faςade in Bloomsbury, no one can grouse that the little bees in the Herakleion Museum are not appreciated in their home country. They are a virtual symbol for central Crete, the subject of solid gold replicas priced up to 35,000 drachmas, and innumerable postcards, motifs for ceramic plaques, cups, coasters and local products and they are the emblem on the 1000-drachma museum entrance ticket.

The bees are displayed in a case above a minuscule gold bull’s head from Mallia, a hairpin from the Idaean cave and earrings of unknown provenance with other finds from neo-palatial sites (meaning those after the 1700 BC earthquake, when the palaces at Knossos, Mallia, Phaestos and Zakros were rebuilt).

The equally miniature nature god in London is strung up in a vertical wall cabinet in Room One (Prehistoric Greece) with various companion pieces. Particularly noteworthy are the large earrings made of double-headed snakes coiled round facing hounds and back-to-back monkeys. Dangling from the circle are 14 pendants – seven discs and seven owls – strung on gold wire threaded with cornelian beads.

The helpful Mr Gates says monkeys signify morning and dogs evening in Aegean Bronze Age art, while the discs and owls could denote the seven days and nights of the Semitic week. The owls, of course, have a funerary connotation and have been found in the Mycenae shaft graves.

Mr Gates also elucidates the meaning of 11 beads in the treasure, five gold, three cornelian and three lapis lazuli. Each shows a hand enclosed round a breast, obviously fertility amulets, “approached with a sense of humor.”

The rest of the collection is made up of three diadems (plain gold bands), five simple gold hoops maybe earrings, a pectoral ornament, a bracelet, four inlaid rings, a gold cup with embossed spiral design and a lot of other beads and pendants of jasper and amethyst (perhaps Egyptian), lapis lazuli, cornelian and rock crystal.

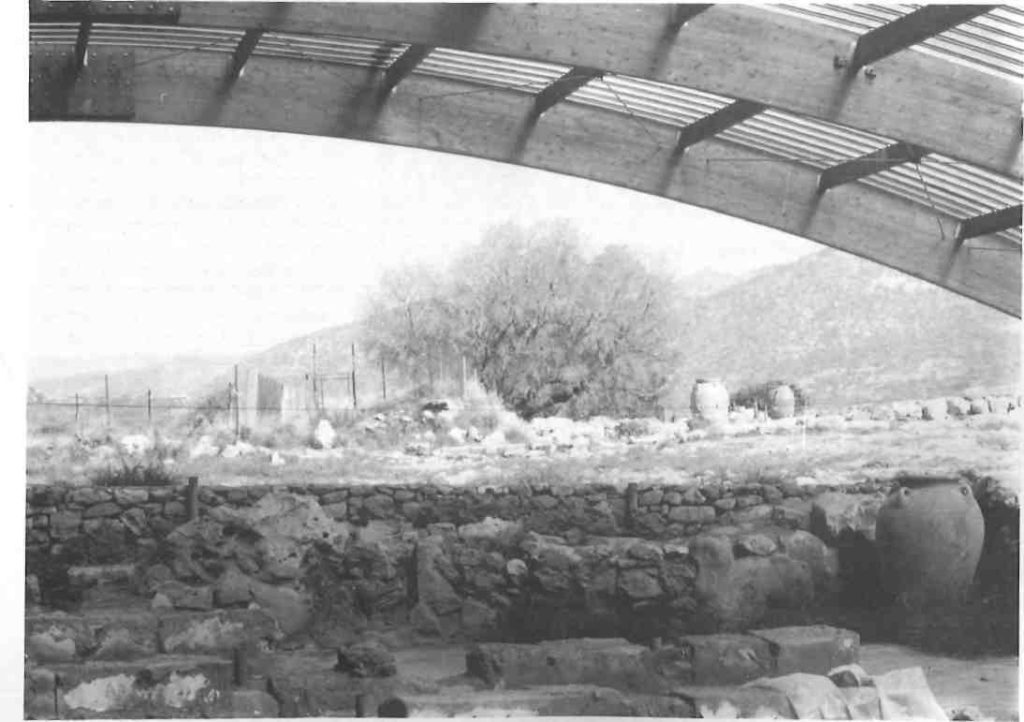

pas~ing the royal cemetery, christened Chrysolakkos in the 1880s by amateur local excavators. French architects

des•gned the arching timber-framed site coverings put up in the last three years under the auspices of the Greek Ministry

of Culture, the work being funded from the EC integrated Mediterranean program allocated to Crete.

Cretan tillers of the soil or shepherds coming by such loot in the 1880s would not hand it to the local pasha. Their thoughts would likely turn to rich travelling sponge merchants visiting the island regularly en route to Turkish and Libyan ports.

Sponge fishing was a booming industry in Greece in the second half of the 19th century, particularly after the development of the compressed-air diving suit. Aeginites travelled all round the shores of Crete fishing for sponges and buying them from locals.

In the years after 1890 at least five sponge businesses traded on the Aegina quayside. Cresswell Brothers traded with them all and was the largest British importing company.

Cresswells handed the collection to the British Museum in July 1891. Presumably it went to London via Aegina and possibly was temporarily stored in the cellar of company premises on the waterfront.

Fortuitously, about that time workmen planting a vineyard on the Windmill Hill property of an Aeginite company employee of Cresswells, Emanuel, broke through the roof of an ancient tomb. Two and two may have been wrongly put together in the kafeneion.

No less a matter of pure speculation is whether the British Museum might allow Greece to redeem at least this miniature treasure, particularly after the Times recent volteface on the far grander Elgin Marbles. But at the very least it could offer a centennial salute to the slant-eyed little figure strutting on his lotuses, perhaps a postcard or two, if not solid gold replicas.