Late in the afternoon on the first of May, 1919, by the old calendar then used in Greece, Archbishop Chrysostomos of Smyrna in Turkey convened an extraordinary meeting of the Great Synod and the distinguished Greek citizens of the city. «Deathly pale, his voice charged with emotion,» said an eye-witness acount, he waved a telegram at them and announced that it was from Eleftherios Venizelos, the Greek prime minister who was then taking part in the post-war Paris peace conferences. After an impassioned speech he concluded triumphantly, «Tomorrow our liberators come to occupy the city. Long Live the Nation.»

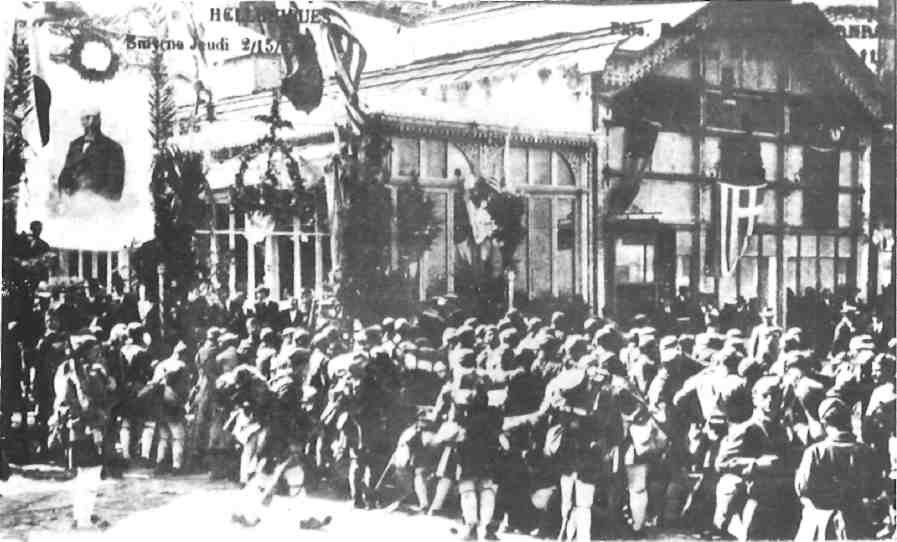

The news spread like wildfire through the town. At last, after months of anxiety and uncertainty, the long-awaited day had come. The local Greeks in a frenzy of nationalism decorated the city, and soon Smyrna was a mass of blue and white flags.

At dawn the next morning the quays and the streets round the spacious harbor were mobbed by tense and almost silent crowds all staring expectantly out to sea. Around seven o’clock an enormous roar split the morning air

as the outline of the large Greek convoy came into view. «They’re coming! They’re coming!» First to dock was the Patris and amid scenes of almost hysterical jubilation Greek troops began to pour off onto the quays as other ships docked all along the harbor.

The people shouted, laughed and clapped, the ships’ buglers played and Archbishop Chrysostomos, resplendent in his golden robes stood in an open carriage intoning «Blessed are they who come in the name of the Lord.» Not expecting any resistance, the troops, mostly unarmed, formed up and with some difficulty managed to march off in all directions through the cheering crowds in order to secure the city.

Not all the citizens of ‘Infidel Ismir’, as the Ottomans called it, were cheering. The administration of the city and the surrounding province was still in the hands of the Turks and they had been only too aware of the approaching Greek convoy. In the Turkish districts of the city they had locked and barred their homes and during the night armed Turks, both soldiers and civilians, had secretly slipped into key positions around the town and prepared to resist. Their unexpected attack caused alarm and chaos among the Greek forces and a murderous battle ensued for some hours, resulting in a handful of dead on either side and many more wounded including some of the spectators. By afternoon, order had been restored and all Turkish soldiers rounded up. But the incident had temporarily marred the celebrations and, for those who believed in them, provided ill omens.

Throughout World War I, when Turkey had fought alongside Germany and Austria-Hungary, many of the Christians of Smyrna and other towns had lived in fear of reprisals, especially after the wholesale massacre of the Armenians in 1915. With the signing of the armistice between the Allies and Turkey at Mudros in October 1918, British, French, Italian and Greek ships had sailed into Smyrna harbor and the Christian Armenians and Franco-Levantines, as well as Greeks, had breathed a sigh of relief. During the peace conferences in and around Paris which followed, the people of Smyrna waited, amid much rumor and speculation, the outcome of their fate.

At the beginning of 1919 in the town of Sevres near the French capital, the conference began between the Allies and Turkey. The small Greek delegation was led by Venizelos, a statesman of international calibre and a brilliant negotiator. Up against the major powers of Britain, France and the US, – each having its own aspirations in Asia Minor – and the particularly tenacious opposition of Italy, Venizelos played a skillful game of international poker to win unexpected territorial advantages for his country. The Italian delegation felt a deep personal antipathy towards Venizelos, seeing both he and his friendship with the Entente, as an obstacle to its ambitions in the Aegean. There, they claimed the Anatolian mainland facing the Dodecanese islands which they had occupied during the brief Italian/Turkish war of 1911, and the port of Smyrna as well. Even as the terms were being hammered out, the situation in Turkey was continually changing. France had occupied the province of Cicilia and the Italians had sent troops to Antalya and its surrounding area which had been promised to them as an inducement to enter the war on the side of the Entente (Britain and France). Greece had occupied Eastern Thrace and Gallipoli, and the Allies, with British forces predominating, were garrisoning Constantinople and the eastern side of the Dardanelles.

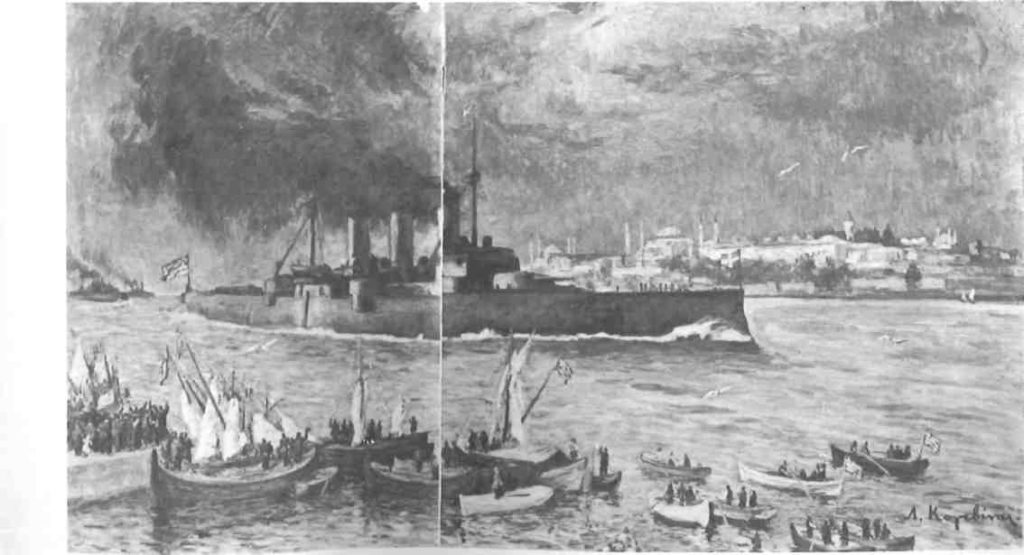

Italy, enraged by what it conceived as unfair favoritism for Greece, secretly prepared its army in Antalya to march on Smyrna and take it by force. The powers at the peace conferences were informed, however, and gave Greece permission to occupy it. Venizelos sent an urgent telegram to Greek army units stationed near Kavala which read, «At this moment the Supreme Council has informed me that at today’s meeting they decided that the expeditionary forces should leave immediately for Smyrna. The decision was unanimous. Long Live the Nation.» Within 36 hours the Greek convoy set sail. It was shadowed most of the way by British ships to ensure against a possible Italian naval attack. Only when anchored off Lesbos were the troops, amid much cheering and excitement, informed of their destination.

Like most of the settlements on the Eastern Aegean coast since earliest historic times, Smyrna had been predominantly Greek. Long a contender for Homer’s birthplace, which is called Phoecea in the Odyssey, it was throughout its chequered existence, as it still is, one of the main ports in the eastern Mediterranean.

With 60 percent of its population Greek in 1919, it was a prosperous cosmopolitan city about the same size as Athens but handling almost double the trade of Piraeus. On the social side it had a good theatre and five large cinemas along with many private clubs and a wealthy fun-loving elite which passed its days in a round of bridge parties, hunts, picnics and balls. From all accounts, the Greek Ball was the event of the season, when young debutantes ‘came out’ for the first time in society. Several newspapers and publishing companies, printing both Greek and translated works, as well as a good education system fed a lively intelligentsia.

By and large, apart from periodic bouts of violence, the governing Turks had not interfered in the lives of the Christian inhabitants of Smyrna, but now their positions were reversed. The Turks for the first time in five centuries were humiliated and in a revengeful mood after their defeat and the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire.

Out of this post-war chaos rose through to power an army officer, General Mustapha Kemal who by dint of his dominating personality and outstanding qualities of leadership reorganized the disunited and demoralized remnants of the Turkish army. Slowly he formed them back into a fighting force. An ardent nationalist, he and his growing number of men, harried the areas of foreign occupation, particularly around Smyrna.

The Treaty of Sevres, finally signed in August 1920, placed the port of Smyrna and its hinterland under Greek control for five years, after which the population by plebiscite or by local decree could opt for union with Greece or not. The Greek forces stationed there were now given the green light by Britain and France to move further inland in order to secure the province whose towns also had substantial communities of Greeks and in an effort to weaken the increasingly threatening influence of Kemal.

Venizelos had also gained for his country the whole of Eastern Thrace and Gallipoli, the ratification that all Aegean islands were now Greek ineluding Imbros and Tenedos, and a place on the International Straits Commission. In a separate agreement Italy had promised to cede the Dodecanese islands except Rhodes. It was a magnificent diplomatic triumph and the Greeks were rightly jubilant.

The ink was no sooner dry, however, than the situation began to unravel. Young King Alexander of Greece suddenly died, and elections were called in November. In an incomprehensible burst of self-destruction, the country voted overwhelmingly against Venizelos and, despite threats from Britain and France, in favor of the return of King Constantine, the father of Alexander, whose pro-German stance during World War I had earned him the enmity of the Entente as well as exile. During the same month Kemal established the National Assembly in Ankara and refused to recognize either of the Turkish sultan in Istanbul or the Treaty of Sevres.

King Constantine’s return in December 1920 caused Greece the loss of French and British support. Two months later Allied representatives met in London to ‘review’ the unratified Treaty of Sevres and agreed on a policy of strict neutrality towards Greece’s presence in Asia Minor. Both France and Italy, recognizing in Kemal the future leader of Turkey, made separate agreements with him which led to their forces being withdrawn from Cicilia and Antalya.

On the contrary the Greek army in Asia Minor launched a new major offensive in March 1921. Now, with King Constantine as Commander-in-Chief, who in the usual Greek tradition had replaced most of the leading officers with those having royalist sympathies, it advanced much further inland towards Ankara, Kemal’s seat of power. A long campaign brought several hard-fought victories for Greece, but it had become dangerously isolated. Devoid of international support, its lines of supply overextended and its troops, which had been fighting since the Balkan Wars in 1912/13, became exhausted.

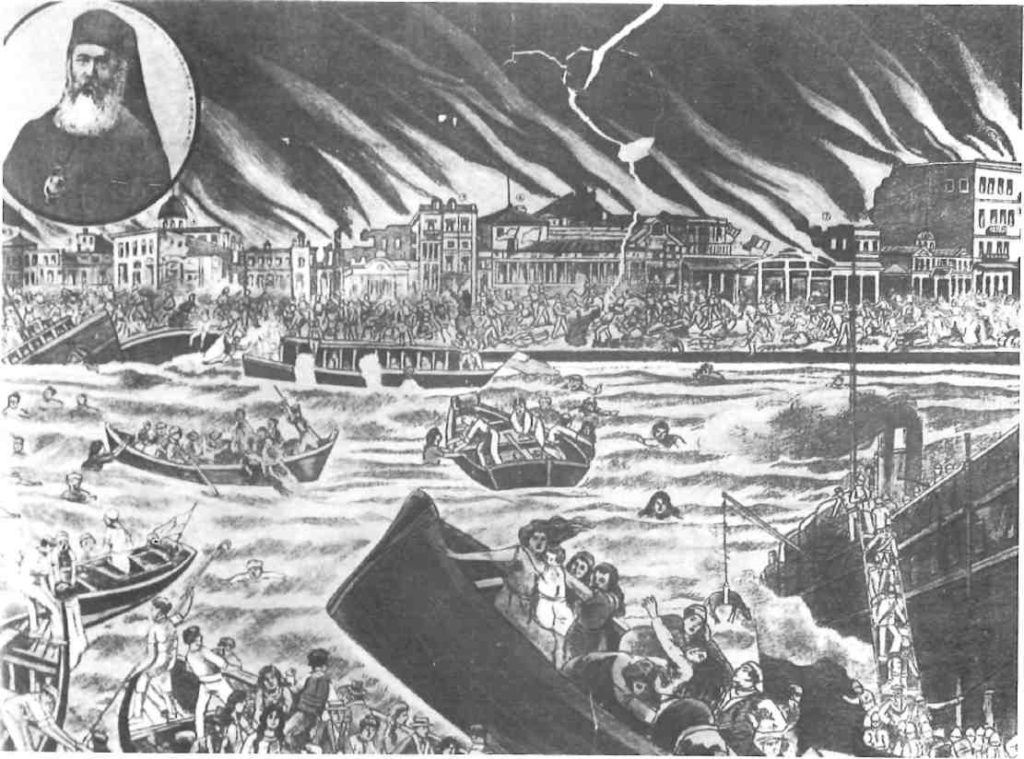

In August 1922, only miles away from Ankara, Kemal launched his long-awaited counter-attack, broke through Greek lines and forced a retreat. Many a courageous rear-guard action was fought, but the Greeks were pushed back to the sea and on September 8 their troops pulled out of Smyrna leaving those hapless inhabitants who had not escaped to the untender mercies of Kemal’s army.

The defeat led to enforced population exchanges, harassment, and further massacres of Greeks in Turkey. It also meant the loss of almost all territory gained for Greece at the Treaty of Sevres, and signalled the end of nearly 3000 years of Greek habitation along the coasts of the Eastern Aegean and the Black Seas.

Even today, 70 years later, the pros and cons and minutae of what was rightly called the catastrophe of Smyrna, are still hotly debated.

katana