Since 1970 United Nations committees have deliberated on the whole question of ‘stolen art’ or removal of countries1 national heritage. At the 46th session of the UN General Assembly in November 1991, Item 23: “Return or restitution of cultural property to the countries of origin” was again aired. Greece voted in favor (as it always has) and Britain abstained (as usual).

At that session the British Permanent Representative to the UN made the statement which follows in part.

“We are sympathetic to the aspirations of those countries wishing to develop and improve their collections of cultural property, but we cannot accept the principle that cultural property which has been freely and legitimately acquired should be returned to the country of origin.”

“Other elements of the resolution… run counter to our belief that the great international collections of works of art constitute a unique resource for the benefit of both the public and the international academic community….”

“In conclusion, I should comment briefly on the remarks made by the distinguished representative of Greece about the works of art known as the Elgin marbles. These works of art were acquired legally in the early years of the 19th century from the sovereign power in Greece at that time… We cannot accept the principle of the return of objects to their country of origin except in the case of illegal acquisition. But we remain ready to discuss the matter further with the government of Greece on a bilateral basis in the spirit of our close and friendly relations….”

The Greek position is that they were taken illegally by Lord Elgin in the early 1800s. Ambassador Antonios Exarhos, the Permanent Representative of Greece, replied:

“I am sure that we all share the view that illicit removal of unique works of art must cease… The question of protecting the cultural property of all nations is all the more relevant now than in the past.”

“May I note that no country is immune to illicit traffic of its cultural property. Therefore it is to everybody’s interest that the 1970 draft convention, now under consideration once more, deprive all involved in the illicit traffic of cultural property from any benefit arriving out of their illegal activities. Furthermore one must take into account especially the interests of countries with a rich historical past which suffered and continue to suffer from the illegal removal of their cultural heritage. In this respect, it would be useful to introduce the element of retroactivity which we consider fully justified by the very nature of the convention. But it is encouraging to note that these concerns are shared by an ever-increasing number of countries adhering to the convention – 71 to date.”

“The substantive aspect of the matter remains within the framework of bilateral negotiations between Greece and the United Kingdom, a country with which we entertain close and friendly relations. The claim for the recovery of the Parthenon Marbles rests with the fact that they were always considered to be inseparable from the monument.”

“The activities of UNESCO and the Intergovernmental Committee have significantly contributed over the years to the enhancement of international co-operation… I note, with satisfaction, that there have been cases where works of art have been returned to their lawful owners. This trend should be further encouraged so that mistrust may give way to goodwill, mutual respect, and recognition of legitimate claims.”

“The draft resolution before us serves this purpose and that is why I commend it for approval at this session.”

From the time it was completed in 432 BC the Parthenon was regarded as the culmination of the architecture of ancient Greece.

The Parthenon is unique in its dual role; it belongs both to the Greeks and to the world. The question now is: should the Parthenon be as complete as possible in one place? The cultural answer is ‘yes’ but Britain sticks to ‘legality’: the marbles were legally acquired and are thus legally held. Where would be the great collections of the world if all legally obtained artifacts were returned to their countries of origin… and what would become of the world showplaces. Paris would lose most of the contents of the Louvre; London, the British Museum; St Petersburg, the Ermitage; Washington, the Smithsonian.

The United Nations has taken another tack. The intergovernmental Committee of UNESCO, in its Recommendation No 1 regarding the restoration of the Parthenon Marbles, proposed that the Secretariat, with the advice and assistance of the International Council of Museums, seek the opinion of a panel of independent experts of international repute. This panel, after studying existing conditions in their present location (British Museum) and the plans of the new Acropolis Museum, would advise the Committee as to the place where the Parthenon Marbles would best be situated.

The Greek Government, under pressure from its then Minister of Culture Melina Mercouri, decided to build a new museum for the Acropolis treasures. In 1986 they announced an international competition for the design of a ‘world-class’ archaeological museum. Subsequently the competition was won by Italian architects Passarelli and Nicoletti. Site chosen is Makriyanni, estimated cost is 15 billion drachmas (90 million US dollars), construction to begin in 1994.

Work has not yet commenced. (Pericles built the Parthenon in 15 years; the new Athens Concert Hall took 35). The Greek government is not likely to have money to spare on such a ‘cultural’ project in the immediate future. It is interesting to see the culmination of the years of effort from 1971 shown in the following table.

1971: Report by UNESCO experts.

1975: Fact-finding group set up.

1977: Study for Restoration of the Erechtheion published and approved by participating experts. Group becomes Committee for the Preservation of the Acropolis Monuments; studies begin covering the restoration of the Acropolis.

1979: Work commences on the Erechtheion.

1983: Study for the Restoration of the Parthenon published. The Greek Minister of Culture criticizes present location in the British Museum. House of Lords passes a Bill allowing discretion for the trustees of the British Museum to consider restitution of cultural objects.

1984: Work begins on the restoration of the Parthenon.

1986: Greek government announces international competition to design new archeologic museum. Restoration of the Erechtheion completed.

1991: Competition for design of the new museum won by Italian architects Passarelli and Nicoletti. UN General Assembly 46th session, Item 23: question of restitution of cultural property. Recommendation No 1: study of best location.

The inability of the Labour Party to win a majority in the House in the April 9 elections disappointed all those who were familiar with Mr Neil Kinnock’s pledge, if he became PM, to aid the cause for the restitution of the Parthenon marbles.

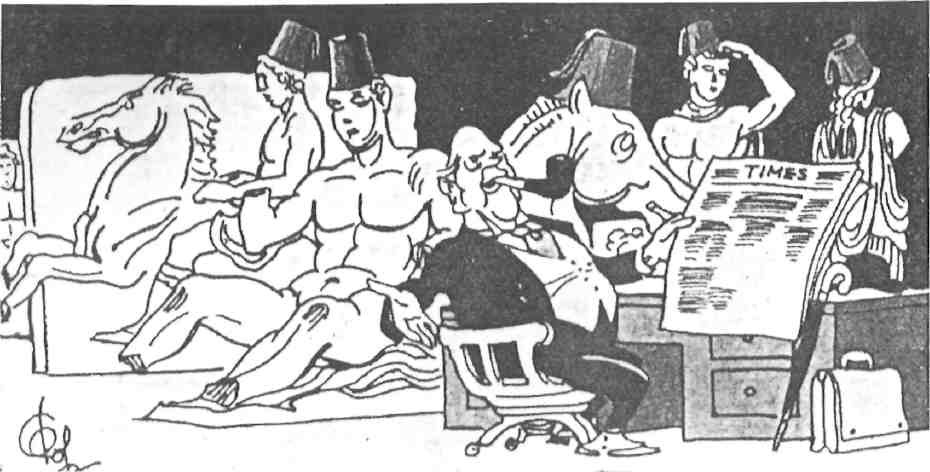

Nevertheless, an editorial published in The Times just a few days earlier is of considerable importance as the newspaper had consistently opposed the return of the marbles in the past. This change of heart on the part of a very establishment periodical may reflect a similar reconsideration amongst the Trustees of the Museum. For this reason, most of the column is reprinted here:

When Lord Elgin embarked upon removing the sculptures from the Parthenon after 1801 his intention was to save one of the great treasures of the ancient world for posterity. The marbles had been plundered, smashed and used as building material for centuries. Lord Elgin legally shipped the statues from Athens and sold them to Britain, for 36,000 pounds sterling, just half his total expenses.

Mr Kinnock’s remarks to Sir Robin Day last week that “the place for the Elgin Marbles is in the Parthenon,” repeated a promise he made to former Greek minister for the arts, Melina Mercouri, in 1985.

His case is essentially the same as Lord Byron’s, who less than ten years after the marbles had been removed heard a prophetic remark from a Western-educated Greek: “You English are carrying off the works of the Greeks, our forefathers. Preserve them well. We Greeks will come and redeem them.”

When Elgin removed the marbles Athens was a town of just 10,000, an obscure corner of the Ottoman empire. He brought them to a city where they would be looked after and viewed by a large and interested public. The British Museum has proved an ideal custodian of the statues, caring for them and displaying them in a handsome gallery. In modern Athens the authorities promise they will be carefully preserved in a new gallery close to the Parthenon.

For the Greeks the marbles have a unique resonance; the Parthenon is a symbol of the cultural unity and continuity of their nation: Greece’s Crown Jewels. The value of the marbles to Greece is incomparably greater than it is to the British. Yet the Trustees of the British Museum have long argued that their responsibility to preserve them is inalienable and to return them to Greece would open the floodgates of endless demands for the return of cultural artifacts that would leave their display cases bare.

There is a clear distinction between valuable artifacts and treasures of intense national significance. If historians and antiquarians cannot tell the difference, then somebody else should do so for them. There are few objects so closely bound up with a nation’s sense of identity as the marbles…

Why in any case should the art of a nation be incarcerated in one place for all time, at home or abroad? The best museums of the future will be those prepared to clear out their cellars, trade their objects and improve their collections.

Nothing is more stifling than the fashion for treating collections as fixed and permanent. It has made museums moribund, their collections augmented only when they can squeeze money out of governments to pay soaring prices for a dwindling stock of artifacts. In the realm of art nowhere is more hogwash talked than on this topic. The marbles should be returned and the cobwebs of museum curatorship swept aside.

Antiquity preserved or cultural loot? Even the British Parliament in 1816 could barely make up its mind. In the debate on the Earl of Elgin’s petition to sell the marbles to the government, the House of Commons split: 82 in favor, 80 against. If the vote had gone the other way, where would the face of the Parthenon be now?