It verified that the tumbledown building was indeed the one where, in 1814, three Greek merchants trading in the city had dreamed of liberty for their enslaved homeland.

Enraged by Austria’s announcement that Greece as a nation “did not exist,”they decided to form a secret society which would plan in earnest for a Greek uprising against Turkish domination.

The three founder members were Athanasios Tsakalof whose Epirot family traded in Russian furs, Emmanuil Xanthos a shipping agent originally from Patmos and a local merchant from Arta, Nicholas Skoufas. They had all previously belonged to masonic or Philhellenic associations which had supported independence for the Christian peoples of the Ottoman Empire, and they drew on this experience as they hammered out the guidelines and rules for their ‘Etairia’.

From Odessa the organization quickly spread through all sections of society in Greece itself as well as in the Balkans and among the Greeks of Russia and Italy. Their initiates, recruited into various ranks ranging from simple peasants and sailors to the rich and powerful, eventually increased at such a rate that the movement began to gather its own momentum until in 1821 the flag of revolt was raised; an event still celebrated every year on the 25th March. Incredibly, a small nucleate state of modern Greece appeared on the map after seven years of war and chaos; the dream of three merchants in Odessa had, against all odds, become a reality.

Naturally the house where the movement for independence had begun was regarded as something of a shrine by the wealthy and influential Greek minority of Odessa which had grown steadily since Catherine the Great founded the city in 1794. The Russian Empress, after expelling the Turks from the area, created a string of towns along the northern coast of the Black Sea, giving them all ancient or Byzantine Greek names. One of those was Odessa, named after the wily Homeric hero Odysseus. To entice settlers to the God-forsaken flatlands she had promised each family 13,000 roubles and free land. About 200 Greeks were among the original inhabitants who had accepted the offer.

With their millenia-old knowledge and experience of the maritime carrying trade they inevitably gained, at least for a time, a virtual monopoly of the port. And, under the protection of the Russian flag, immense fortunes were made by some Greek shipowners on the Aegean and Black Sea routes mainly by transporting grain from the vast cereal-growing plains of the Ukraine.

The community thrived during the Crimean War but suffered the reverse in WW I when the city was occupied by German forces and the Dardanelles were closed to trade. But it was the Russian Revolution which sounded the death knell of free trading and caused thousands of Greeks to leave south Russia. Odessa, like the rest of the Ukraine, was fought over by Byelorussia (White Russia), Poland, the Bolsheviks, and internal warring factions, not to mention small detachments of allied troops until in 1920 it became part of the Soviet Union. Again in WW II it was occupied by German armies after withstanding a destructive two-and-a-half-month siege. Little wonder, given the city’s short but chequered history, that the origins of the house of the Philiki Etairia had been completely forgotten.

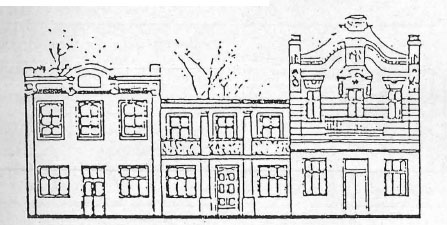

Today there are, according to the local guides, approximately 4000 ‘pure’ Greeks, those claiming their lineage from both parents and many others of mixed parentage, in the port. It was their association Ellada which, in 1988, pressed for an urgent meeting with the Executive Committee of Odessa’s City Council in order to discuss what should be done about the newly-discovered historical building. Both the Council and the History Department of Odessa’s University were very cooperative and all agreed that, despite daunting problems, both technical and financial, the house along with those supporting it on either side at number 16, 18 and 20 Krasnipereoulo Street should be saved. The Council promised to examine the site immediately and to proceed with the work as fast as the prevailing circumstances allowed, while the local Greeks undertook to provide materials which are unavailable on the Ukrainian market and to offer accommodation and food to experts and workers coming from Greece.

with the two houses supporting it on

either side, on Krasnipereoulo Street.

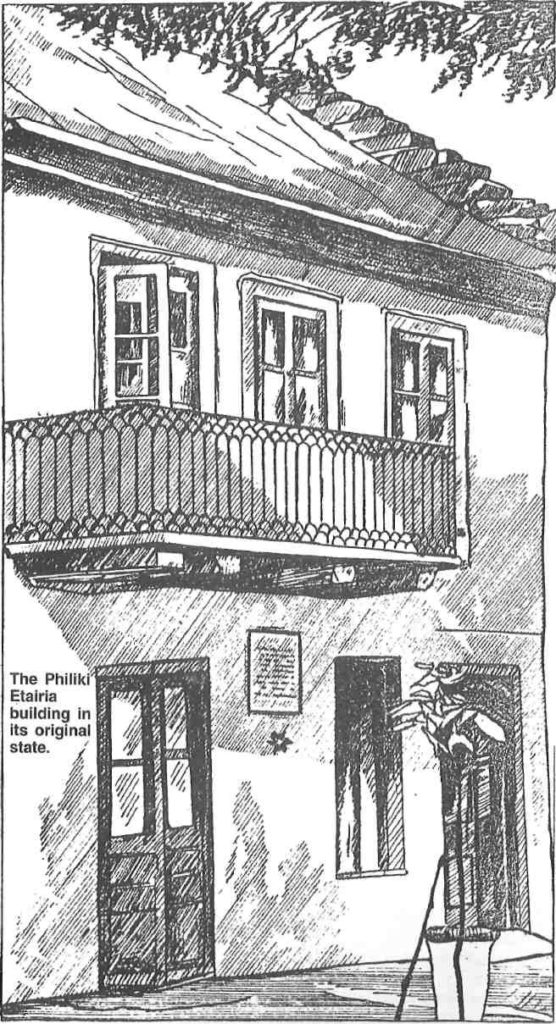

Before reconstruction could even begin, tons of rubbish had to be removed and as all three houses were in such a ruined state they had no choice but to demolish them and begin rebuilding from scratch. Number 18 will be faithfully reconstructed in every detail, both inside and out, so as to be an exact replica of the original house as it was in 1814 with a shop on the ground floor and the apartment on the second. While only the exteriors of the neighboring houses will be as they were. Inside there will be halls for lectures and exhibitions.

The Greeks of Odessa, no longer wealthy, desperately appealed for help in supplying the building materials required. And a handful of people in Greece responded by providing what support they could. So far Georgios Megkos-Enislidis, an Athens-based businessman has donated over 30 tons of wall tiles, handmade terracotta roof tiles, parquet and marble flooring, enough fittings for ten bathrooms and specially sculpted marble balcony supports, faithful copies of the originals which had been badly damaged. The spirit of cooperation proved infectious and the agents of the Odessa-based Black Sea Company offered to transport the materials free of charge. Even the stevedores of Piraeus, after a union meeting, decided to wave their loading fees. Professional people involved, such as Anthony Papaioannou, a civil engineer, offered their services and expertise as well as helping cope with the. myriad export documentation and official translations required.

A thousand dollars and a much needed Greek typewriter were donated by the little known Union of Pontic Officers – Alexander Ypsilantis, an association named after the prince who, as a leader of the Philiki Etairia, raised the initial signal of revolt in 1821. A further 6000 dollars have come from the President of the Piraeus Chamber of Commerce. Up till now, the venture which is nowhere near completion, has costed a not so small fortune, the bulk of it being provided by the Odessa City Council. Unfortunately work on the buildings has now slowed perceptively due to the present lack of financing available in the Ukraine.

The local Greeks and city fathers, unaware that the historical house of the Philiki Etairia still existed, had in 1979 already created a small museum in a ground-floor apartment not far from the bustling port, in Lastotsrov Street. There, papers, books and memorabilia connected with the secret society and its three founder members are on display. But it is not big enough to hold all the exhibits which will hopefully soon be transferred to their rightful home once reconstruction work on the new museum is completed. Small as it is, it has already attracted half a million visitors, mainly sailors, tourists and students but early on it received groups of Greek parliamentary representatives headed by Yiannis Alevras, then Speaker of the Parliament and the Greek Women’s Association.

Since then there have been no further organized visits from Greece and no official recognition of the important historical work being carried out in Odessa. No aid, financial or otherwise, has been received from the Ministry of Cultre in Athens or indeed any other state organization to help recreate the house which is so important a part of modern Greek heritage.

Now that freer trading is opening up in the northern Black Sea area particularly since the first of December last year when the Ukraine opted, for the second time in recent history, for independence, agreements are once again being signed with Greek shipping, tourist and industrial companies. It would be a fitting if the historical house of the Philiki Etairia where independence for Greece was so successfully planned over a century and a half ago were now to open its doors to the public.