The high point of winter entertainment in Athens is certainly Apokries, or Carnival. The extent of the live music scene here may be unique to any European capital, and the most exciting music to be heard is without doubt the distinctive Greek laiki musiki, urban popular music, or laiko tragoudi, popular song, (as it is most commonly called). This is true whether it is being played today by ‘veteran’ artists who were its early developers before the end of the 1950s or by its younger interpreters who are, in turn, developing the laiko tragoudi in its classic forms with new compositions. This story of the laiko tragoudi is an introduction to a wonderful, and interesting, night out.

Two musical traditions came together in late 19th and early 20th century Greek-speaking urban centres of the East Mediterranean and in immigrant communities of the US. One was a non-commercial tradition which developed in the male-dominated teke (hashish-den) and prisons of the rough and ready ports; the other, a sophisticated commercial tradition of the cafe aman, the Middle Eastern music cafe. It is thought to be so-called after the frequent cry aman! (alas!) sung by both male and female professional singers. In the first context, amateurs played the bouzouki (long-necked, similar to the Turkish saz) and the baglamas (its diminutive cousin popular in prison as it was easily constructed from a gourd). They composed rhyming distichs to amuse themselves as they smoked hashish. In the second, the instruments were those of the classical and popular Turkish ensembles, the outi (similar to the lute), kanonaki (zither) or santouri (similar to kanonaki, but with strings that are struck, not plucked), den (circular drum, similar to tambourine), zilies (finger cymbals), and violin (usually replacing the traditional lyra or short-necked lute).

Music in the cafe aman derived from Arabo-Persian musical practices with emphasis on the melismatic, wailing amane songs, and on popular Asia Minor dances, the qifteteli and the karsilamas, a solo and a couple dance. The women singers, more common than men, or professional dancers, would perform the qifteteli. An early popular singing star, Rosa Eskenazi, who died in 1980, got her start this way. Dances associated with males in the teke, kafeneion, or prison were the zeibekiko, a solo folk dance originating in eastern Anatolia, and the basapiko (butchers’ dance) performed by two or three men side by side with their hands on each others’ shoulders. In the cafe aman, dance was provided as spectacle, and part of its function, in certain establishments, was to attract male patrons, titillate them and stimulate their good mood (kefi), which would make them more generous customers. Kefi in the teke could also be achieved with dancing, but the commercial objectives were perhaps not so integral and the only dancers were the customers themselves. It is not clear at what point the cafe aman encouraged customer dancing, but it is clear from later musical repertory, which included such popular folk dances as the tsamikos and the kalamatianos, both social dances rather than solo (with little provocative potential), that it became a feature.

The earliest record of its presence in Greece is 1874, but cafe aman was probably known before that. It was certainly established in Asia Minor Greek culture, and its music and songs may have been improvised. Eventually, it became standardized due probably to early 20th century gramophone recording. The commonest theme was the erotic relationship in the Smyrnaiko (Smyrna-style) popular song. The amanedes remained, at least in performance, more spontaneous laments. The teke tradition concentrated on themes of hashish, prison, gambling, and other low-life pursuits. The erotic verses were frequently ironic, bitter or threatening, overwhelmingly from a male point of view. There was much imagery from rural folk poetry. It is not known when low-life themes entered the repertory of the cafe aman, but, by the 1920s, there was a distinct genre on 78 rpm records of hasiklidika (hashish songs) performed by cafe aman companies and singers. It was probably in the establishments catering for a low-life clientele that these songs were first heard.

Early gramophone recording companies based in Europe and England sent expeditions out to Greece and Asia Minor to record at the turn of the century. (The first Greek studio was established in 1930.) It was natural that

Asia Minor artists and styles dominated from the beginning as there was no equivalent professional class of urban popular musician in Greece. It was in the US, in the early 1920s, however, that the first rebetiko, soon to become the no.l popular style, was recorded. Rebetika, manghika, hasiklidika, zeibekika is how the Gramophone Co. Ltd of England described its popular recordings in a 1926 catalogue. The term rebetiko stuck, probably thanks to the record companies, to describe the low-life songs described above. Smyrneika came to distinguish the Asia Minor style of music (not the amanedes, which always retained this epithet) from that of the bouzouki which was to cause a sensation ca. 1930 in Greece.

The first recording of rebetiko featuring bouzouki was imported to Greece from the US about 1930. It was a huge success and record companies began the search for players good enough to put on record. In the low-life of Piraeus, which revolved around the teke and the bordello, they found Markos Vamvakaris and his parea of manghes. Respectable society viewed these men as a faceless bypokosmos (underworld) and, while undoubtedly some were criminal, the manghes were of a subculture probably more devoted to style than crime. Impeccable dress and grooming, a lot of ‘attitude’, inventive slang, usually vulgar, all expressed certain values shared by these men who stood out from the context of poverty in which they lived. While many were married and supported families, some kept company with prostitutes, at least with those who shared their street-wise attitudes. The tekedes they frequented were often backrooms in those kafeneia which were commonly near bordellos and served as a kind of waiting-room for these establishments.

While women did smoke hashish, they rarely did so in the teke, which, like the kafeneion, was an overwhelmingly male preserve, although women might work around them, fetching water and cleaning the pipes. They were certainly around the more informal tekedes set up in a small number of refugee shacks in Old Kokkinia and in the area behind Aghios Dionysios in Piraeus where many people were directed to set up their ‘temporary’ homes. It was a notorious centre of prostitution. Although hashish was illegal, laws were only sporadically enforced until 1936, when Metaxas decided to ‘re-moralize’ Greeks.

Little is known of the women of this subculture, either those who related to the manghes domestically or as prostitutes. We know about the men because interest has focused on the earliest bouzouki composer-performers, invariably men, and, to extend the story of the rebetiko to include women singers, we have to move into the world of prostitution, part of the ‘secret’ history of Greece and of popular music, too long to tell here.

In the eyes of respectable society, however, the women who sang in the cafe aman and later, in the bouzouki tavernas and kentra, whatever their domestic status, received from many the same contempt shown to prostitutes.

The bouzouki musicians, now in demand, brought their rough voices to the rebetiko, but their verses, often crude and poetically primitive, had to conform to precedents already established by recording companies. In other words, their music and song had to be limited to suit both the time allowed by the record and the tastes of a wide audience which reached beyond the backroom of the teke.

There was a certain amount of competition between the formerly amateur and semi-professional bouzouktzides and the Asia Minor musicians, who had dominated popular music from the beginning, had taken positions of power in recording companies after 1922 and were instrumental in the founding of the first musicians’ union in 1928.

Markos Vamvakaris first recorded in 1933 and was a big success. He and his friends formed a quartet and soon they and others, including Asia Minor musicians, were playing regularly. While the recorded verses became even more stylized, hashish, other low-life themes, and heavy slang continued to predominate, as they did in performance. It was a period of prolific activity, the ‘Golden Age’ some say, of the rebetiko. Tavernas began to hire bouzouki orchestras for engagements lasting for months. Towards the end of the 1930s women began to sing with them, one to an orchestra, and for more limited engagements in kafeneia.

Women singers were sought after because, regardless of what some people might say, from the point of view of tavern-owners and many musicians, they gave a place more ‘class’.

Further, it was believed that the presence of women would help draw women customers, making them feel more comfortable. Another reason may have been the crackdown on hashish initiated by the Metaxas regime in 1936. Bouzouki players, known for their use of hashish, were severely harassed by the police in Piraeus and Athens, though not so much so in Thessaloniki, whence many of them moved. Some were imprisoned and exiled to islands. As women were not known for their use of hashish nor for frequenting the places in which it was smoked, it was thought that their presence would calm suspicion, be it justified or not. Women and bouzoukia together were an innovation.

While women were prominent in the cafe aman and were beginning to be noticed in the professional dimotika (folk) circuits in the provinces (dominated by gypsies, and from 1922, by Asia Minor musicians) where they became hugely successful in the 1930s (Rosa Eskenazi, Rita Abatzi in both, Yiorgia Mittaki later on dimotika records), they came later to bouzouki rebetiko, on record and stage. Sophia Karivali, Ioanna Yiorgakopoulou and Daisy Stavropoulou are reputedly the first women to sit on the palko (low platform for musicians) with bouzoukia in the late 1930s.

By the end of the 1930s, there were from 10 to 20 bouzouki venues, catering to various classes of clientele, from pimps and prostitutes on their nights off from the bordello to ‘nice’ middle class people. In the cafe aman, however, the music, its performers consumers and venues, remained urban lower class. A gramophone, by the way, was a regular feature of street life thanks to wandering players who entertained for tips.

Censorship, imposed in 1936, forbade themes of hashish, prison, gambling, etc, and the use of related slang. This led recorded verses even further from their original social context, though in performance it remained. Talents emerged with poetic power that rose above these restrictions. Chief among them was Vassilis Tsitsanis, the young man from Trikala who came to study law in Athens and became instead the foremost composer and versifier of the laiko tragoudi – as the rebetika were now officially categorized by recording companies to avoid troubles with the law. One result of this combination of censorship and talent was the further expansion of the popular audience, as songs began to address the pains and joys of everyday people, not just members of a streetwise crowd, or those who fancied themselves as such.

The Occupation brought a ghastly halt to recording activity and performance. Hashish use, however, flourished again, prostitution was out of control, and some men’ had money of dubious provenance for entertainment. Slowly, performance revived, restricted to the hours before curfew. Some musicians worked. Some couldn’t face it. Many died, especially those in the ranks of the Asia Minor performers who were very poor. Their deaths marked the demise of the cafe aman and its style. Many musicians refused to work on political grounds, for music was popular with the Occupiers.

A number of bouzouki composers – they always played too – appeared. Apostolus Kaldaras, Yiannis Papaioannou, Yiorgos Mitsakis, Apostolos Hatzichristos and Manolis Hiotis, like Tsitsanis, collected their songs until the day when recording studios opened again. The great Sotiria Bellou began her career, playing her guitar and singing in small tavernas for tips.

Recording resumed in 1946 and, despite the Civil War, or maybe partly because of it, people set out in droves to enjoy themselves. With censorship back under local control, second generation composers and versifiers like Tsitsanis dropped the hashish and other low-life themes without much regret. He had, in any case, never been a hardcore member of the teke set. It was left-wing sentiments now under attack. Songs glorifying ‘bohemians’ and cutting loose in the taverna were in vogue, as the archondorebetika (high class rebetika). These served as an antidote to the darker laments of poverty and hard times, which, with their heavy zeibekiko rhythm, spoke to the hearts of people. Rena Stamou and Prodromos Tsaousakis sang in the early 1950s a number of these songs, rarely heard today, many of them very fine, written by all the leading composers.

By this time there were a number of establishments featuring rebetika and archondorebetika. All classes were catered for, from the aristokratia of wealthy men with their expensive girlfriends who frequented the Alexandrianou near Nea Filadelfia for its back room teke, to the kentra (night-spots) – some offering taverna food, others fruit, nuts, and wine – at the still sparsely populated seaside at Tzitzifies, which catered for a lower class clientele. The taverna of Jimmy tou Hondrou (Fat Jimmy’s) in Athens was popular with lnice’ people. Besides Bellou and Yiorgakopoulou, there was now a growing number of women singers such as Stella Haskil, Marika Ninou and Rena Stamou. Anthoula Alifrangi, Rena Dallia, Anna Chrysafi and Sevas Hanoum were important, as well as Voula Gika, reknowned ‘second voice1. Kaiti Grey, Poly Panou and Yiota Lidia, also began their careers in the 1950s.

The post-war period began full of promise. Recording companies had high quality compositions and artists to promote. The lafka began attracting not only more consumers for records but for the many magazia (shops), as those in the business call all variety of establishment. Greek popular music was now recognized by the erudite as true ‘culture’ and, in 1948, the learned (as opposed to self-taught, the normal condition for popular musicians and singers) composer Manos Hatzidakis organized a lecture on the rebetiko illustrated by Vamvakaris and his parea and Sotiria Bellou. By the end of the 1950s, however, it sounds that something went wrong, for compared to what had gone on before, not only did rebetiko lose its vitality but the laiko in general was in deep trouble.

It is difficult to see these things in terms of cause and effect. Several factors merged during these years. The three double chords of the bouzouki were exchanged for four, making Western scales and chords and the instrument easier to play. Composers – almost always players, too – became ‘stars’. Furthermore, the instruments were electrified, making it possible to fill larger venues with sound. Many kentra became more like American nightclubs or cabarets, offering dancing shows and programa. Women singers often stood up to sing. Male singers followed, as did the star bouzouki on occasion. From one or two bouzoukia, guitar and baglamas, orchestras had expanded to include piano and accordeon, dropping the baglamas. After 1956, the usual one woman singer was joined by one or two others often chosen for their looks. Bordellos became illegal, and some women took the opportunity to change profession. Glamor began to be a serious style; Kaiti Grey was the most glamorous.

Many artists began touring, especially in the US, where there was big money in the booming 1950s. Some stayed. The older generation of composers like Vamvakaris went out of style, their new compositions were rejected by the record companies, and no one wanted them in the kentra. Vamvakaris began touring the rural festival circuit with the dimotika musicians.

Some singers were superceded. Prodromos Tsaousakis, whose voice was a prototype for the young Stelios Kazantzidis, faded before the younger, more versatile man who became the singer of the 1960s, along with Kaiti Grey. They had many hits together. In short, the laiko changed so dramatically it was hardly recognizable but for the bouzouki and the dances. Record companies began to withdraw support for the new compositions of Tsitsanis, although he continued to work steadily, and occasionally to re-record his old classics with new singers.

The 1960s were the decade of the skiladika – high priced kentra, tons of smashed plates, whisky and tackiness. Electric organs helped deafen the crowds which flocked to these places. They were popular – with the Indian, Egyptian and Turkish music that record companies insisted be ‘composed’ (filched from records) and fitted out with Greek lyrics of the poorest quality. Even the influence of composer Mikis Theodorakis, who set the poetry of George Seferis and Yiannis Ritsos to the music of the bouzouki and the dance rhythms of the zeibekiko, did not inspire most record companies to support high quality compositions. On the positive side, however, there were more ‘traditional’ magazia, and these continued with a low profile. The humble taverna Nisos Idra, for example, gave a home to Sotiria Bellou and a number of others who were now veterans of the classic laiko tragoudi.

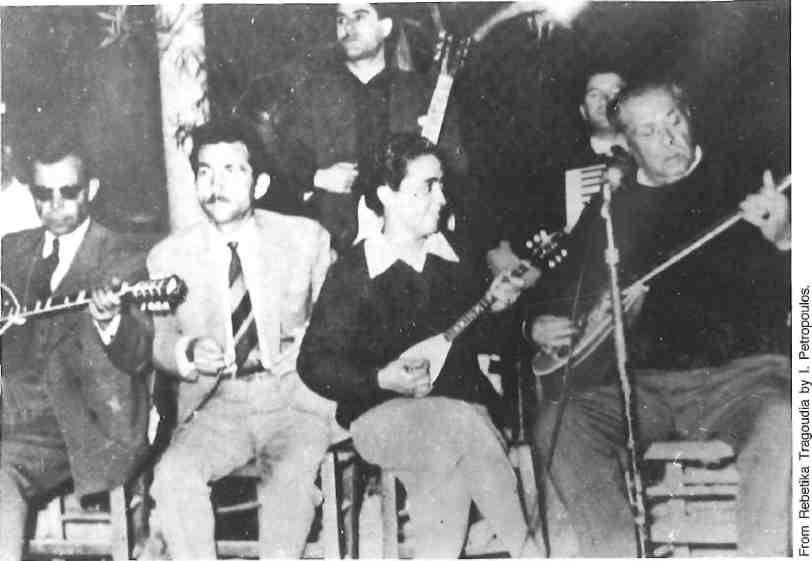

A crowd of young people – students, intellectuals, actors, professionals – began to frequent this taverna, and to scour the Monastiraki flea market for old 78 rpm records. Others began to collect, and later publish, life stories of veterans. The most complete autobiography, that of Markos Vamvakaris, is an important document of lower class pre-war urban Greece and of the rebetika. An important, non-scholarly, anthology of songs and photos was published in 1968 (Rebetika tragoudia, by Ilias Petropoulos). The classic laika and the older rebetika were ignored, however, by state-controlled radio and TV (introduced in 1966). It was still possible to hear classic songs in live performance. Also, popular Greek cinema regularly featured scenes in night spots as well as many stars of the post-war generation. The magazia, old records, the occasional LP of newly recorded old songs, and a few small concerts kept veterans and their music in the eyes of a small public, who understood that they were preserving a true national treasure, (cf. Vamvakaris on various labels, and Sotiria Bellou on an important Lyra series still in progress, at no. 12 to date).

Beginning in the early 1970s and peaking after 1975, scores of 78 rpm classic rebetika and laika songs were re-released on LP anthologies (eg. Rebetiki Istoria, 6 vols on EMI). Many young people, inspired by these songs, learned to play popular instruments (often at schools), formed amateur groups (usually 1940s style, not cafe aman), and played for friends or in small tavernas and clubs. Towards the end of the 1970s, experienced professional musicians began to form groups (eg, the Opisthodromiki Kompania). Around 1980, established Athenian magazia began to host these groups, a move which confirmed that the laiko tragoudi was once again a commercial success.

A high point in the revival was the 1981-82 season at Sampanis taverna which featured Rena Stamou, one of the original rebetisses. The 1400 seats were filled night after night as she presented classic songs from.her vast repertory, played by foremost bouzouki virtuoso, Yiannis Moraitis, one of the few players today who learned his skills from older ‘teachers’ -Vamvakaris, Tsitsanis and others. (Watch for Rena’s new LP on Sonora, out soon).

With careful attention to original 78 rpm recording styles, kompanies recorded old songs. Established singers like Haroula Alexiou, Glykeria and Yiorgos Dalaras began to follow their lead with LPs. Record companies were now, finally, willing to accept neo laikes compositions and veteran artists were often asked to record them. Certainly one of the best, perhaps the most characteristic, examples is Laika Proastia, a cycle of songs by Ilias Andrianopoulos, sung by Sotiria Bellou (Lyra).

This was the decade of hugely popular (and huge) concerts, where the older and younger artists came together at the Lykavittos Theatre in 1982 and elsewhere. Many kentra presented the older generation, a trend which continues today. The emphasis was on inexpensive food and drink, even in the large places. The skiladiko was definitely our. A number of beloved figures had died – Panos Gavalas and Sevas Hanoum, both singers, Tsitsanis, composer Apostolus Kaldaras and others. Several kompanies split by the end of the 1980s and those still going don’t enjoy their former massive popularity. On the other hand, composers are exploring new sounds, combining laika, folk, and Byzantine elements to create new music, such as Nikos Zidakis.

Others remain devoted to the classic laiko style, using more traditional music and less obscure poetic imagery, composing in the tradition of Tsitsanis and others (eg. Vangelis Korakakis). Rebetika and lafka, the very best of the old and the new classics, can be easily enjoyed in live performance. You may appreciate the older artists even more when you understand something of what it has cost them to keep their art alive. You may admire the younger generation, who truly love their Greek traditions. Don’t delay in hearing them. Age and market forces always threaten.