Since it became lined with elaborate town houses in the 1880s and 1890s, it has remained the terrace of Athenian elegance. Down this broad avenue foreign dignitaries have passed to present their credentials to the King, especially after he moved into the more modest palace on Herod Atticus Street in 1935 (now the presidential mansion). Since 1930, tourists too, map in hand, have traversed their way from the Benaki and Byzantine Museums which were opened to the public within a year of each other.

The first luxury apartment block appeared on the corner of Herod Atticus Street in 1900; in the 1930s these became more common. Proliferating after World War II, they began replacing the private dwellings built half a century earlier.

In later years, the Hilton rose (that concret ‘thumb1 set across from the Acropolis, as they said in those distant days) (1963) a favorite destination, especially for Americans at first, but then for Athenians, too. Most recently, and further along, the new concert hall has opened p the “Megaron of Music” Athenians proudly call it, every one of them converted last year into ardent Mozart fans. All these, along with the American Embassy (erstwhile Bauhaus initiate Walter Gropius’ homage to modern classicism) as well as the fine traditional mansions which house the chancelleries of France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Egypt and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. All add cosmopolitan ambience to the only avenue in the city that can boast the name of “boulevard”.

It certainly is not Sunset Boulevard. Leoforos Vassilissis Sofias, named after the consort of George I when the monarchy was restored in 1935 only three years after her death, was formally laid out in the 1890s. Lying at the foot of the Kifissia Road as it entered Syntagma, it was originally conceived as a promenade of recreation and serenity, planted with a double row of pepper trees, adopting the example already set in Queen Amalia Avenue, leading east out of the square.

Although it has passed through an number of phases of decline and renewal, Queen Sofias Avenue is still thought of as an aristocratic thoroughfare. Ignore the car horns and the traffic jams, there are still things to be seen here.

Athens is a city of excess. When it was no more than a dusty provincial town in the mid-19th century, it was glorified as a jewel set in earth’s crown. When it grew bigger and had acquired mansions, cafes and tramways, it turned overnight into the ‘Paris of the Eastern Mediterranean’. And when one day smog started to clog the city, then it suddenly became an urban monster to avoid. Few things express the Greek character more precisely than its tendency to go beyond limits. So it comes as no surprise that, when the Greek government decided to plan a new avenue where the new bourgeoisie and the Greek merchants of the diaspora might build their houses, what is now called Vassilissis Sofias Avenue came to light, sparkling like a polished diamond.

The Athenian middle class that evolved during the 19th century was solidly oriented towards prevailing European ideals of the time. Musical education was a must for all the girls of wealthy families, the novels of Jules Verne excited the imagination, and German toys filled the windows of the Ermou Street shops. No matter that the streets were muddy in winter and dust-choaked in summer. Before the economic backwardness of the Greek state, a large number of Athenians built a facade of romantic idealism, almost bizarre, which was evident as late as 1922, when the defeat of Greece in Asia Minor buried the dreams of countless generations. This idealism could find no better expression than in architecture.

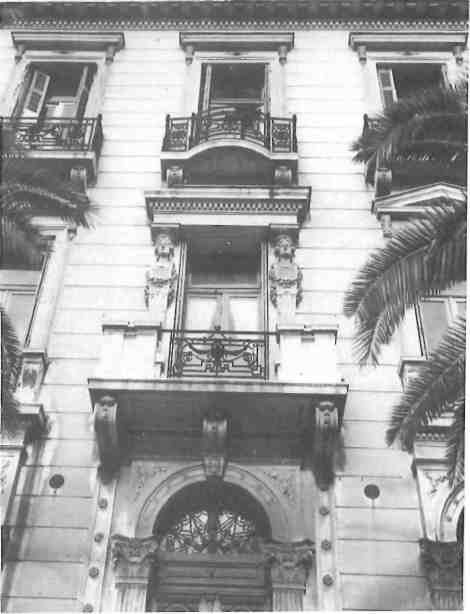

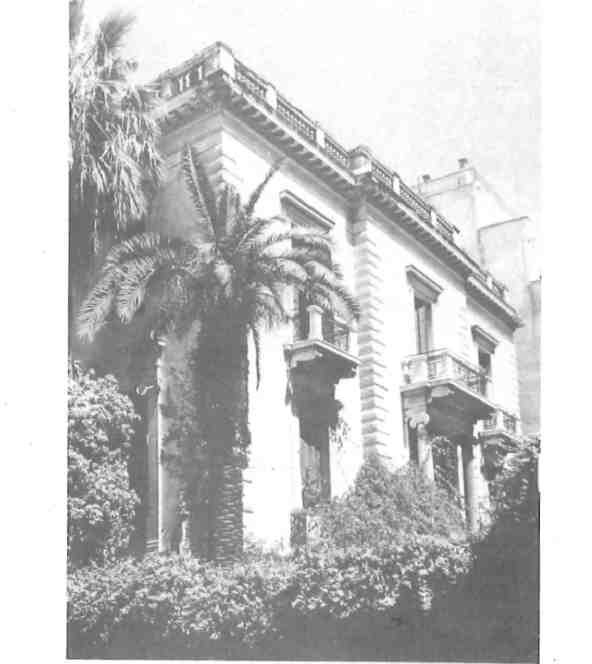

Neoclassicism in Greece, unlike Greek Revival in America or Regency in England, was not just another style in architecture. It was an ideological persuasion. That is why it spanned a century and its late, modernized examples persisted until the 1930s. Vassilissis Sofias Avenue still preserves some of the finest examples of the opulent, often exaggerated, versions of this architecture.

For any Athenian who has memories that go back before the 1950s can easily tell you that no other street in Greece makes you feel what a dignified thing Athenian neoclassicism was.

Graceful classic fagades, colonades, statues, flowered gardens, palm trees. The present Athenslover should have in mind that Vassilissis Sofias has always been, till today, a showcase of extravagant architecture. The now delapidated early 1950s apartment buildings (fine examples are the Nos 21, 25, 33, 37, among others), which replaced charming mansions, were the ultimate ‘chic1 of the period. At the end of the avenue, Athens Tower, erected in 1972 and designed by the now fashionable architect Yiannis Vikelas, was the first skyscraper in Greece. And it might be well to remember that just opposite, on the corner of Mesogeion Avenue where the Ktimatiki (mortgage) Bank rises today, stood the notorious Villa Margarita, probably the greatest piece of neo-Wagnerian romantic architecture in Greece, until well into the 1960s.

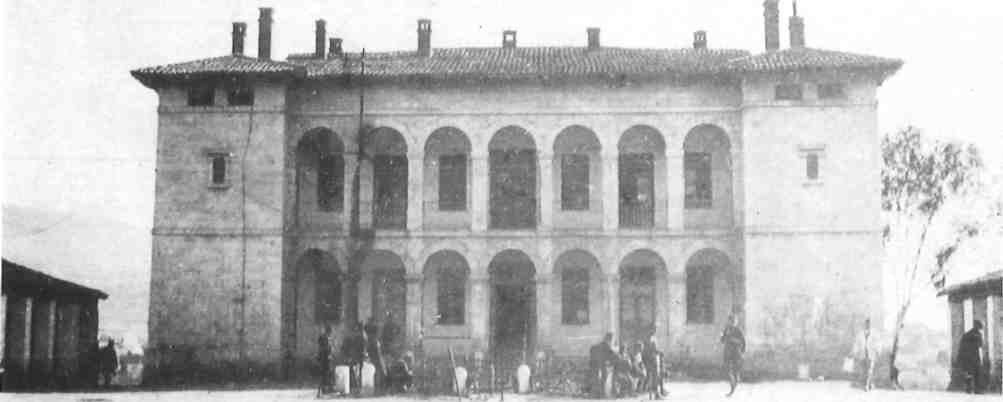

Indeed, like most of Athens, Vassilissis Sofias grew in very disorderly fashion. Stamatis Kleanthes1 Villa Ilissia and the handsome Evangelismos Hospital stood for 20 years amijd a scattering of military barracks and stables before the first noble mansion was built, the Stournaras-Merlin house between Sekeri and Merlin in 1861.

“The city of Athens”, wrote Henry Miller in the Colossus of Maroussi, “is a city of startling atmospheric effects; it has not dug itself into the earth – it floats in a constantly changing light, beats with a chromatic rhythm. One is impelled to keep walking, to move on towards the mirage which is ever retreating.” We know that Henry Miller had walked along Vassilissis Sofias Avenue just before World War II. From there he could stand in the shadow of the Lycabettus Hill and feel the aura of the Acropolis. These are magic things, one could say today. No doubt! Greece has nothing to do with the realistic world. It is a metaphysical challenge. And Henry Miller realized this as soon as he set his food on Greek soil and felt completely “detached.”

Yet, nefos and all, there are still January twilights today when flocks of migratory birds wheel in the sky as no where else, and the contre-soleil on Mount Hymettus still evokes Pindar’s beautiful epithet Violet-crowned’ Athens.

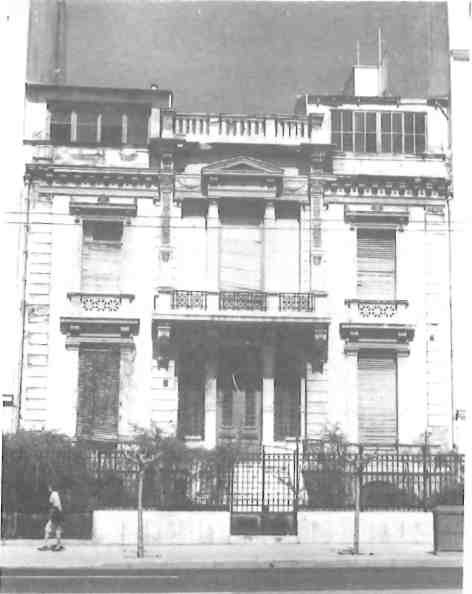

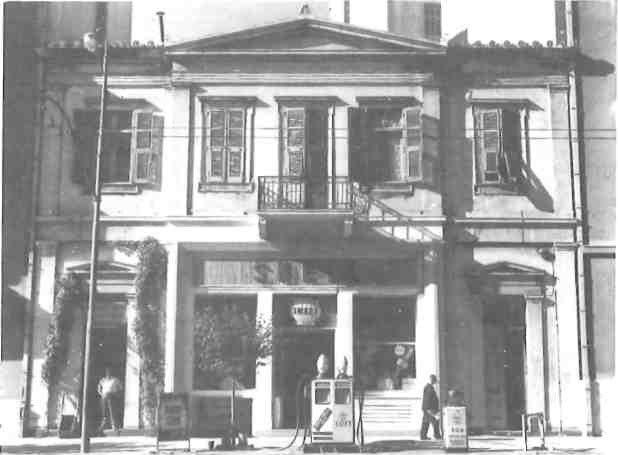

Next time you walk down the avenue towards Syntagma and distract yourself with the cats that purr along the National Garden’s handsome wrought-iron fence, make sure you turn your head to the right and see the remains of the glory that this avenue was. Fine architects of the time (1880-1920) have left their mark. Sadly, many examples were demolished over the period 1950-1978. Nevertheless, one can still admire the town houses that the German architect Ernst Ziller designed for wealthy families: the Embassies of Egypt and Italy (both built before 1900) and his best work, the Stathatos Mansion (1895, at the corner of irodotou, No 31) which will now house the Vergina exhibition.

The Benaki Museum is well-known. It is housed in what at first was the Harokopos Mansion (No 17), which was bought early in this century by Antonis Benakis, son of the Alexandrian cotton magnate Emmanuel Benakis and brother of the celebrated writer Penelope Delta. It was designed by Anastasios Metaxas, a prominent architect who also built the fine Villa Danai for banker Karolos Merlin, which now houses the Embassy of France.

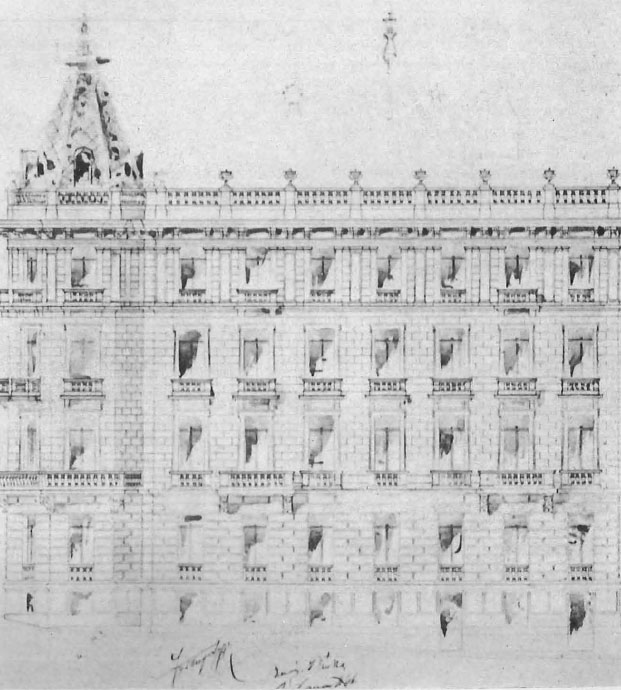

Fine houses were gradually erected all the way to today’s Hilton area. A marvel of its time was the imposing Pezmantzoglou apartment building, erected at the corner of Vassilissis Sofias and Herod Atticus Street, designed by Ziller and completed in 1900. At one time it housed the US Embassy. The greater part of it, along with its steepled tower (a Ziller trademark), was torn down in the early 1960s, leaving a remnant at No 4 which today is occupied by the Embassy of China.

Another impressive house was the Stournaras-Merlin Mansion, designed by Kaftanzoglou, the architect of the Metsovion Polytechnic. In the rancorous debates about neo-classical Athenian architecture at the time, it was he who called Ziller’s neo-Renaissance house build for Schliemann an ‘incurable leprosy’. The Stournaras-Merlin House could still be seen at No 11 till its demolition in 1963. An impressive post-modern building, designed by Yiannis Vikelas, took its place, finally, last year.

Across Koumbari Street from the Benaki Museum once stood the Kazoulis House, also inhabited by Alexandrian cotton millionaires, and inherited by the Yiorgandas family of Kifissia by marriage. It had a two-storey Greek Revival portico by Metaxas worthy of Gone With The Wind. A block above, at No 21 was the graceful Petros Kalligas mansion (now demolished). On the opposite side of the street, beyond the classic ‘Varaghis’ building and the neo-baroque Military Club on Rigillis, one comes to the oldest and probably the most romantic site of the Avenue: the Villa Ilissia, now Byzantine Museum, erected in 1840 by Stamatis Kleanthis for the eccentric Duchesse de Plaisance, in a pleasing Florentine style. The will of this extensive landowner was ignored by her French and American next-of-kin and in a rare moment of inspiration her property was bought in toto by an act of Parliament for pittance. As a result, there is on the same block, the Athens Odeon, the War Museum and the Naval Club. And on the opposite bank of the one-time Ilissos River, the Athens Centre of Scientific Research and the National Gallery (pretty good for a single act of Parliament!).

The charming but simple Syriotis Mansion (No 23), the Art Nouveau Voglis House (No 35, bliult in 1900 by Anastasios Chelmis), the Vergotis Villa (No 39, a fine example of pure Athenian neoclassicism) were all sadly torn down in the 1960s. The demolition of two more mansions (No 45 and No 49) in 1978, completed the destruction of a formerly graceful and romantic past.

Yet Vassilissis Sofias Avenue still retains an air of charm and old world elegance. And if one happens to walk up this Athenian boulevard on a clear spring day, he can easily chase the dream that made Henry Miller feel so detached in this changing light and chromatic rhythm.