With the sudden disintegration of the Soviet Union, the emergence of Russia as a powerful independent state and a redefined political status quo in East/West relations, the long-debated fate of ‘Priam’s Treasure’ is back on the international agenda for discussion. Despite a flurry of press reports and semiofficial announcements last year alluding to its continued existence, the precise whereabouts of the priceless Trojan gold collection remains shrouded in uncertainty.

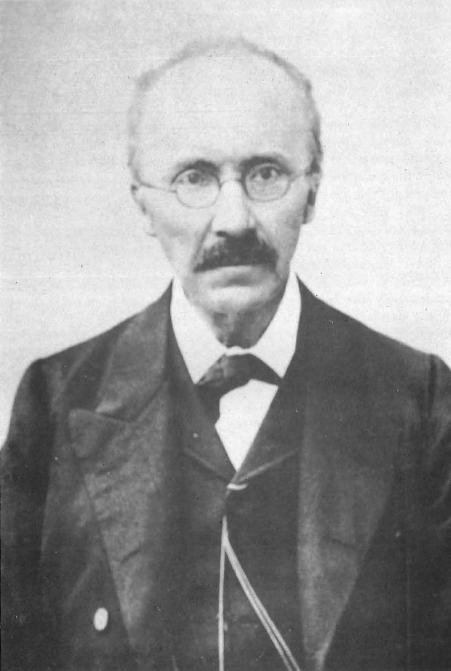

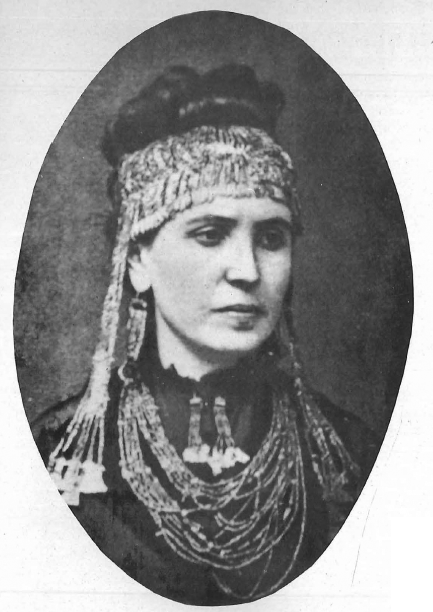

Heinrich Schliemann, the German amateur archaeologist and erudite reader of Greek mythology, financed and conducted the first major excavations at Hissarlik in Turkey to prove both to himself and the world that Homer’s Iliad was based, albeit loosely, on historical fact. Overjoyed at uncovering what he believed to be Homeric Troy, he called the rich find of gold from Troy 11 after Priam, who, in myth, was the city’s last king.

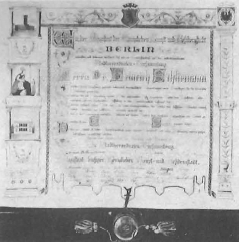

Refusing to sell his unique and much sought-after treasure, Schliemann eventually decided, to Greece’s everlasting disappointment, to donate it to Berlin, which had only recently been chosen as the Reich’s capital for the newly-unified German states. In turn, he was awarded with honorary citizenship. There, far from its original home on the sunny Mediterranean, the collection remained the pride of the Ethnological Museum, later the Museum of Early History (Ur und Fruhgeschichte), its existence happily unaffected by Germany’s defeat at the end of World War I or by the financially crippling reparations demanded by the signatories of the peace treaty. It wasn’t until many years later, during the Red Army’s all-conquering advance on Berlin in 1945, ‘that it apparently vanished into thin air, leaving only a cloud of speculation and rumor in its place.

Opinions differed. Many were certain that the gold objects had been destroyed forever, melted down either in the conflagration caused by Allied bombing, which gutted the city, or by looters. Others were equally positive it had fallen into the hands of Soviet soldiers, sold piecemeal on the thriving post-war blackmarket , reduced to souvenir status, and dispersed throughout the United States.

To fuel this viewpoint three one inch-long pendants, perhaps once part of a headdress, were bought back by Berlin’s Museum of Early History last year. They had been sold by an unnamed American who had acquired them in Germany after the war. Authenticated as Trojan gold by the museum, there remains some doubt among curators as to whether they are from Priam’s treasure or some other collection. lt was the second such purchase in recent years.

Despite rumors and official denials to the contrary, many art experts continued to believe that the treasure, which had been stored in three great chests at the outbreak of hostilities, was intact and in the hands of the Soviet authorities. Klaus Goldmann, one of the Berlin curators involved in its recovery said recently that they had always known it was in a walled-off vault in Moscow’s Pushkin Museum. “We know the location of the strongroom and where it is being stored.”

After more than four decades of deepening mystery, Glasnost produced some chinks of light on the matter. In 1990 a Russian archaeologist writing in a Soviet youth newspaper mentioned that the treasure had survived and that it was being stored in the USSR. This was instantly denied officially, once again. But last year the American magazine Artnews caused a furore by publishing an article by two young Russian art experts, Konstantin Akinsha, the magazine’s Moscow correspondent, and Grigori Kozlov, an employee at the Pushkin Museum, which reiterated that Russia did indeed hold the treasure along with many other works of art and collections and called for it to be returned to its rightful home or at least to be put on view. The same magazine reproduced a 1956 document allegedly signed by the then curator of the Pushkin Museum stating that Priam’s Treasure was secured in the vaults of that building. Irina Antonova, the present director, has remained tightlipped on the issue, refusing to meet foreign museum representatives and journalists alike.

When Allied planes began bombing Berlin in the early years of the war, a specially designed building of reinforced concrete . was erected in great secrecy in the wooded area of the city’s zoo. There, the three chests containing the treasure were stored for safe-keeping until sometime in 1945 when they disappeared. Since then , suspicions, accusations, denials, red herrings and cold-trails have abounded but no substantiated facts.

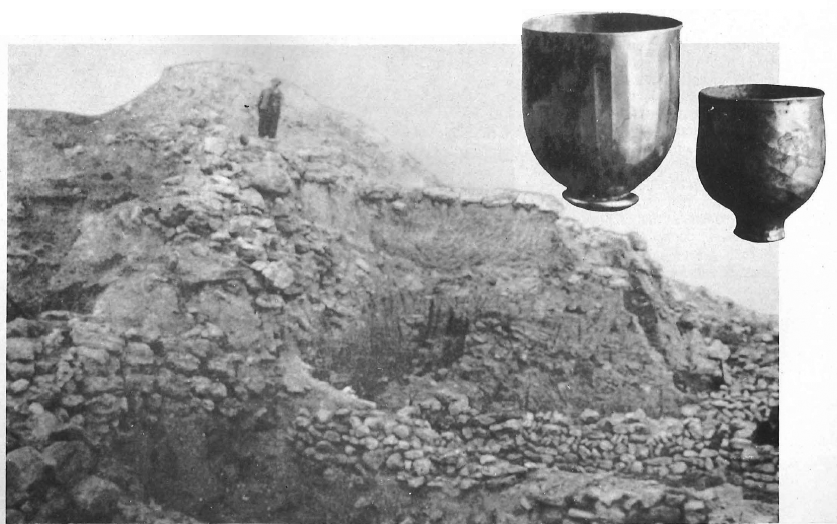

Schliemann’s dig at Troy (Hissarlik) and Two gold beakers from Troy.

Recently there has been speculation that the chests may have been handed over officially, if clandestinely, to a chosen representative in the Red Army high command in a desperate effort to preserve the collection intact and as part of the ‘Replacement in Kind’ policy. Plans for these ‘payments’ were laid in Moscow as early as 1943 by the foreign ministers of the main Allied nations and were known only to a select few.

Russia had suffered appalling hardship and deprivation during the advance of Hitler’s armies which had ravaged and plundered their way to Stalingrad, Moscow and Leningrad where the palace of Tsarkoe Selo was looted, the panels of its famed Amber Room’ dismantled and sent to Kaliningrad (Konigsberg) (their existence is still an open question) and the exquisite palace of Petrodvorets, commissioned by Peter the Great, was stripped and dynamited. It was reasoned that in the event of Germany’s defeat, it would not have the money to pay reparations and therefore, the ministers agreed, it would have to forfeit its treasures.

The Soviet Union was by no means the only one of the Allies to exact ‘payments’ of this type and that deals were struck in the twilight years of the war is clear although no nation had released papers or details of these undercover transactions. It is known, for example, that Germany’s gold reserves, banknotes and archives of the Reichsbank, along with art objects which had been stored in its. vaults, were moved from Berlin to AngloAmerican-held territory in 1945. And during President Carter’s term in office, the United States returned the historic crown of Saint Stephen to Hungary as a goodwill gesture; it had been stored in Fort Knox.

As far as Priam?s Treasure is concerned, the Soviet Minister of Culture Nikolai Gubenko acknowledged that ‘booty stores’, first mentioned in the Isvestia newspaper by a Moscow Uni versity art historian last spring, did in fact exist but made no specific mention of the Trojan collection . To gain time, he used the old British ploy of setting up “a special commission to look into the matter” but emphasized that the countries concerned must work together on a basis of exchange. “Since 1952 the USSR has returned more than one million items to Germany including paintings , drawings, graphics, stamps, coins and antiques and Germany has given back only eight icons,” he explained.

It is not yet clear if there has been any change in official thinking since last month’s dismantling of the Union.

Perhaps Boris Yeltsin, Russia’s new strongman, has it in his power to solve the continuing enigma of the vanished treasure which materialized so unexpectedly out of what for centuries was believed to be the mythical site of Troy.

It would certainly be a joy to art lovers an·d historians everywhere if it were allowed to re-materialize and once again be put on view for all to see and admire.