Only a few weeks after the surprise acquittal of former premier Andreas Papandreou, of charges of responsibility for widespread corruption under his socialist administration, the government is facing a possible election showdown over a parliamentary seat vacated by a minister who was found guilty at that same trial.

At the same time, it is facing growing reaction over its new series of economic austerity measures as well as its relative failure to resolve its differences with neighboring Balkan countries.

The post-trial domestic political upset came somewhat as a surprise, considering that the court’s leniency was seen as deliberately designed to satisfy all sides, and particularly the left-wing opposition. All sides felt that the divisive issue of the notorious Koskotas scandal had to be put aside, so that the country could concentrate on more pressing issues such as the economic crisis and Greece’s foreign policy problems.

To the contrary, post-trial political tremors led to a series of minor demonstrations by the socialists, to a refusal by the sentenced minister to buy off his jail term and to insist on imprisonment, and to a conservative newspaper attempting to put up the money in his place and against his will.

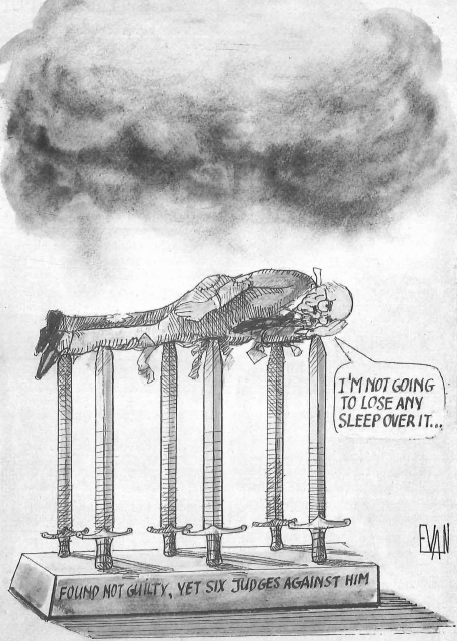

The developments showed that the socialist opposition appeared bent on making political capital over Mr Papandreou’s acquittal on January 17. Though the 73-year-old ex-premier scraped through his acquittal with a 7-6 decision on the main charge, he orchestrated a number of rallies to celebrate the event and to call for general elections.

Former finance minister Dimitris Tsovolas who was given a two and a half year jail term but was allowed to buy it off, refused to do so and dared the government to jail him as specified under the law.

In an unexpected development, and in an attempt to put an end to what it described as “a political show designed to make a hero of himself,” conservative mass circulation daily Eleftheros Typos put up the required one and a half million drachmas to buy off the term. Mr Tsovolas took legal measures to prevent this, though under the law it is understood that any third party could do so even without the sentenced man’s approval.

The socialist party also refused to appoint another deputy to take Mr Tsovolas’ parliamentary seat. As a re

sult, an election must take place in Athens for the vacant seat, an election pursued by the socialists as a national vote of no-confidence against the conservative government. If the government looses the vote by a large margin, it might necessitate new general elections, considering that at present it only holds a two-seat parliamentary majority. Eventually, the political tension was considerably defused by a responsible change of tactics in the socialist camp. Moderates seem to have prevailed, and the party may finally agree to put up the money so that Mr Tsovolas need not go to jail, although it tends to petition parliament for a pardon, so that the former minister’s sentence would be written off and his parliametary seat restored. At presstime, these matters had not yet been finalized.

Prior to all this, media and political parties had almost unanimously welcomed the acquittal, purportedly because it would have defused the political climate.

“The court’s verdict must be received with satisfaction,” conceded influential conservative daily Kathimerini in its lead editorial. “Because at a very crucial moment for the country it offers a way out of the political impasse, averts any further tension and at last allows the State to deal with the real problems plaguing the country.”

Mr Papandreou’s victory, most papers and politicians agreed, was a Pyrrhic one because his acquittal was achieved with a narrow seven-to-six vote and because the court found two of his ministers guilty of related charges. It sentenced them respectively to between ten months and two and a half years imprisonment, but in neither case would they actually have to go to jail. The ten-month jail term for former transport and communications minister George Petsos was suspended for three years. Former finance minister Dimitris Tsovolas was allowed to pay off his term at a rate of 1000 drachmas for each day sentenced, but he lost his parliamentary seat due to the suspension of his civil rights for three years.

Another minister on trial, Mr Papandreou’s deputy prime minister Agamemnon Koutsogeorgas, had died of a stroke during the hearing last year while trying to disprove thoroughly documented evidence that he had received a two-million-dollar bribe to formulate a law favoring now imprisoned banking and publishing magnate George Koskotas.

At the end of this ten-month marathon trial and testimony by more than one hundred witnesses, Mr Papandreou was acquitted of charges of authorizing the transfer of the financial assets of state corporations to Koskotas’ bank, of authorizing the favorable settlement of a debt to the state by a hotelier and private friend, of violating his duties as a prime minister, and of accepting 90-million drachmas in bribes from the banker.

But six of the 13 presiding judges, one short of a majority, called for a guilty verdict.

“Mr Papandreou should have followed more closely the financial transfers of the state corporations, and must have been fully aware of the fraudulent and highly publicized illegal activity of banker George Koskotas,” said the proposal of the dissenting judges. “The financial scandal is accepted as a fact by all. It could not have taken place without the knowledge and approval of the government at the highest level, including the accused prime minister.”

Mr Papandreou later said that he was delighted with his acquittal, but angered over the sentences against his two former ministers. “The government’s disgraceful attempt to destroy our Party, and me personally, failed miserably,” he said, adding that new general elections were now necessary.

Mr Papandreou’s alleged involvement in the financial scandal, as well as his controversial private life, were responsible for his government’s defeat in the 1989 elections. But his acquittal, however unconvincing, is expected to improve his popularity ratings.

While jubilant Socialist Party supporters staged rallies throughout the country to celebrate the verdict, the conservative government also expressed a certain satisfaction. Athanasios Kanelopoulos, the deputy prime minister and government spokesman on the case, said the government had not interfered in the judicial process and was satisfied with the outcome. He called on the public to turn its attention to more pressing issues such as the economy and the Balkans.

Indeed, this was a reminder of the real problems Greece faces, ones which are likely to plague the country in the months and years ahead.

To begin with, enthusiasm has subsided somewhat over Greece’s success at the EC Summit in Maastricht in

December, as well as over EC initial decisions to delay the recognition of the Yugoslav republics. While Greece appeared to have had considerable support for its bid to enter the Western European Union (WEU) Defence Structure, as well as for its demand that the Southern Yugoslav Republic of ‘Macedonia’ not be recognized unless it changed this historically Greek name, matters have not proved to be that easy.

Bulgaria, once a staunch anti-Turkish ally for Greece, in mid-January became the first country in the world to recognize ‘Macedonia’. Turkey said it will follow suit, particularly so as to satisfy the large Moslem minority there, and so did EC member Italy, a country which is vying with the French, British and Germans for influence in the Balkans. In brief, and despite Greek protests, there appears to be a growing trend in the European Community for recognition of all the Yugoslav republics, including ‘Macedonia’.

The general Greek concern is that its relations are deteriorating with all its neighbors: Italy, Albania, ‘Macedonia’ and Bulgaria. And that this is proving to the benefit of its easternmost neighbor, Turkey.

On the economic front, the government is facing a major uproar over its latest austerity measures, announced only a few days after the Papandreou trial verdict. According to these, and contrary to all expectations, there will be no pay increases whatsoever in 1992 for civil workers and employees, while even more taxation and steep increases in public utility costs and basic services, and an extra tax on property owners will be imposed.

Not only the socialist and communist opposition and the major unions, but even sections of the conservative establishment, have threatened a ‘relentless’ campaign against the government in an attempt to have these measures rescinded. The government, in turn, argues that it has no choice but to comply with European Community economic directives as a condition for achieving integration with the more advanced community members. Overall, therefore, Greece seems set for yet another turbulent year ahead.