The main 1991 cultural event on Aegina was a mid-summer pistachio festival put on by the town council to promote the tangy pink and green nut, cousin to the cashew, which in this century has become the island’s chief export. Pistachios come in every imaginable guise on Aegina harborside. An elegant zachawplasteio like the Aiakeion has crisp sweetmeats coated in pretty slivers. The Lalaounis restaurant offers cool green pistachio icecream. Strung along Leoforos Dimokratias are the many nut-sellers, from the kiosk run by the Agrotikos Synetairismos Aiginas (Agricultural Association of Aegina) to the independent growers doing their own marketing and weighing and bagging on the spot.

As head of the Lyceum after Aristotle, and equally interested in biology, Theophrastus is the first Greek on record to have given any attention to pistachios. Writing about 300 BC, he mentioned their medicinal use, but with reference to the aromatic gum from the terebinth (Pistacia terebinthus), called tsikoudia or kokorevithis in Greek, or mastic (Pistacia lentiscus). The nut tree Theophrastus knew of only by repute produced fruit like almonds.

The pistachio is an astonishingly late arrival to Greece. Despite a passing reference to a planting in 1815, the first verifiable cultivation, reported in an agricultural journal, was in Zakynthos in 1856. In Athens systematic cultivation was begun in Psychiko by D. Pavlides fn 1860. Trees were planted in the Royal Gardens and Agricultural School in 1869. Not till the turn of the century did systematic growing begin in Aegina, where ideal conditions have led to its becoming, apart from tourism, the chief means of livelihood.

“The island lives from fistikia” says Christos Stratigos, a member of the agricultural association council, selling guaranteed genuine local nuts from the quay kiosk patronized by thousands of weekending Athenians, holidaying tourists and cruise ship passengers stopping off for shore excursions to the temple of Aphaia.

Opinion along the waterfront as to when, by whom and from where pistachio nut trees were first brought to the island is as various as the vendors: from Egypt, Syria, Persia, 100 , 150 years ago. Opinion is unanimous only on Aegina pistachios being superior in quality, flavor and aroma to all others because of the island soil and the blessing of its climate, mild in winter, with long hot summers and low humidity, rarely above 65 percent.

Proof of quality is the alleged prevalence of fraud. Even on Aegina, iniquitous traders try to pass off inferior, but cheaper, pistachios from elsewhere in Greece as authentically Aeginite. Since January 1 this year, such practice has been illegal: the term fistikia tis Aeginas may now be used only for pistachios really grown on the island, others to be fistikia typou Aeginas. Buyers seeing the ambiguously cunning fistikia t. Aeginas might ask what the f stands for. More scandalously still, nuts sold tis Aeginas from mainland stalls may even be imported from abroad.

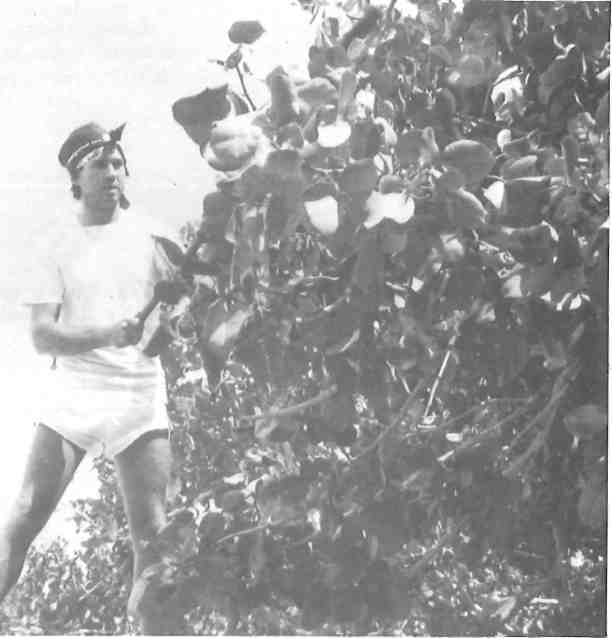

Foreign fistikia are cheaper, not harvested with tender loving care by hand, but probably rudely shaken down by machine. Proud Aegina growers keep up the tradition of family harvesting, the season predictable, beginning between August 15-25, ending on September 15. Islanders desert other business, even close their hotels early September, to throw themselves enthusiastically into stripping the trees by hand in the dappled shade under broad leafy boughs.

Vendors are right in claiming Levantine origins for the trees. Earliest plantings on the island from about the 1860s were possibly made by settlers from Smyrna and islands near the Asia Minor coast where the tree had come from the Middle East.

Among Greeks from Smyrna and Alexandria gravitating to Athens in the later 19th century were members of the Peroglou family. Nikolaos Peroglou left the patriarchal home in Alexandria and, with his wife Julia, who come from a Constantinople family long resident in Athens, bought a house on the corner of Koumbari Street and Leoforos Sofias where two daughters were born.

The Peroglous later moved round the corner to Kanari Street where the family remains, while on the site of their former house, a handsome neoclassical mansion designed by Anastasios Metaxas was built and acquired in 1910 by the Benaki family when they, too, moved up from Alexandria. Today it houses the Benaki Museum.

The Peroglou family took to summering in Aegina on doctor’s orders, to benefit the older girl’s bronchitis. “They liked it there,” says Annette Manuehdes, a granddaughter who lives in Kanari Street and is director of the Benaki Phytopathological Institute in Kifissia, founded by Emmanuel Benaki, who was a minister of agriculture in an early Venizelos cabinet.

“So my grandfather bought land in Aegina, built the Villa Julia, and planted several kinds of fruit trees and various nuts. When he noticed pistachios did best, he concentrated on them.”

“Pistachio trees are slow-growing,” she says. “They take at least ten years before they begin producing. My grandfather won a prize for nuts grown in his Aegina garden at an exhibition in Washington DC in 1915, so the trees must have been put in by about 1900.”

Her many childhood memories of Aegina are of late August and early September days joining in the family gathering of ripe nuts from five in the morning till heat drove them indoors, then of afternoons dehusking, sitting under pines in the seaside garden facing over to the island of Angistri and the mountains of the Peloponnese.

“Methods of cultivation have changed little in Aegina over the century,” says Manuelides. “Traditional forms of irrigation are still employed. The use of fertilizers and pesticides remains empirical. The huge plantations in the last 30 or 40 years round Lamia and elsewhere are elaborate in comparison, with modern methods of cultivation.”

The fourth generation of Peroglous is now enjoying the Villa Julia, built of pale Aegina stone in 1893 on the main road running south of Aegina town to Perivola and Perdika. Part of the original property has been sold, but the oldest trees are kept and cultivated lovingly for sentimental reasons. “They still bear fruit, but quantity decreases after about 60 years,” says Manuelides.

Many Peroglou trees are smaller than others to be seen on the island, as Nikolaos Peroglou believed female trees should be kept low, with only a few male trees allowed to grow tall, so their pollen would fall on the surrounding females below. Manuelides is sceptical: “Pistachios are wind-pollinated,” she says.

As a plant pathology specialist, her favorite research has been into pistachio diseases and pests. “The trees are highly susceptible to insect attack.

“They always need spraying at the right time, so the minimum amount is used.”

If not suffering from pests, pistachios may be adversely affected by variations in the weather. Last winter’s excessive rain led to lush foliage but fewer, poorer nuts. But generally the island suits the tree well, as it likes the limestone soil and being comparatively resistant to excess chlorine flourishes by the sea.

A side-effect of extensive 20th-century pistachio cultivation on Aegina has been the almost total depletion of fresh water wells on the north-western coastal plain. Older crops like vines needed no irrigation. Systematic irrigation of pistachios from existing and newly sunk wells left only brackish water, more recently replaced by pure sea water.

Pistachio growers must now buy water, adding to costs. “Only if they do all the work themselves is there a living to be had,” says Manuelides.

Her expertise began with a doctorate on potato diseases researched in Bonn after undergraduate study at Athens Agricultural College. She abandoned an early ambition to be a physician from aversion to the ill. Studying plant diseases seemed a reasonable alternative. “And plants are so easy, so simple, so grateful,” she says.

The library at the Institute in Kifissia runs from Loeb Classics editions of Aristotle’s Parts of Animals and On Breath, through Darwin’s Origin of Species to a treasured treatise on pistachios written by her grandfather and published by the Royal Agricultural Society of Greece in 1916. The booklet gives an account of the history and cultivation of pistachios, with instructions on how to propagate them by grafting Pistacia vera onto Pistacia teberinthus, the wild species.

Peroglou believed pistachio cultivation began in Greece “about 55 years ago”, that is about 1860. He thought the trees were first cultivated by Arabs, who called them fastous and introduced them to Sicily. In the 1900s the trees were introduced from Syria to Italy, from where cultivation spread to the south of France and Spain, he wrote.

A later authority, Panos Anagnostopoulos, writing in 1935, claims Greek pistaki derives from the Persian pista, while a more recent study published in Larisa in 1980, by Nikos Brousovana, traces the derivation back to the Arabic fust. He claims pistachio cultivation goes back 3500 years in Syria, spreading to Asia Minor in the time of Alexander the Great, round the Mediterranean during the years of Roman rule, and to California in 1853-4.

Iran today has more than half the pistachio trees in the world, (five million), followed by Turkey with about a third, Syria with eight percent, then Greece and Italy with about three percent each. Pistachios are now grown in Greece around Corinth, Evia, Chalkidiki, Thessaly, the Cyclades and Crete.

Back on one of the earliest Greek pistachio plantations, Villa Julia on Aegina, the current family project is restoring the old house, beginning at the top by reroofing and replacing 90 damaged palmettes of the 300 round the edge of the roof. Coping with creeping damp on the interior plaster of the notoriously porous Aegina stone is another enterprise, as well as trying to locate round porcelain door knobs and keys for the old locks. The hope is restoration will be finished for the centennial anniversary.

Pistachio seller Nikolaos Kleanthes, who has 200 trees, in his small shop on the waterfront.

Annette Manouelidis, on the terrace of Villa Julia

AEGINA: “The Eyesore of Athens”

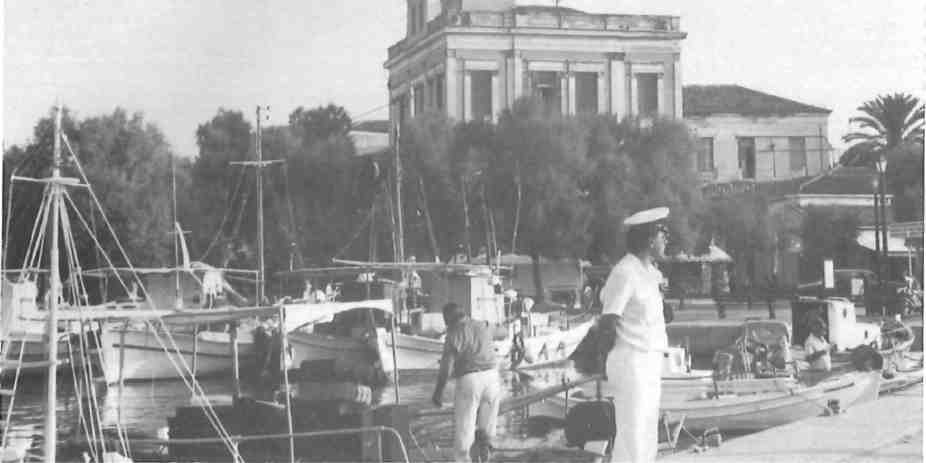

Apart from its repute as a pistachio producer and holiday resort, Aegina (provisional population 5440 in this year’s March census) was known as the seat of the first capital of the modern Greek state, where John Capodistria took up the presidency from January till October, 1828, in a building now housing island archives.

The island was then deprived of limelight when Nauplia took its place as capital and it has remained in relative obscurity. Over grilled octopus and ouzo at 11 in the morning in the fish market psarotavernes, the price of pistachios for growers and vendors respectively is the commonest topic of discussion, and how to promote the nuts, which have admittedly become a luxury at about 1700 drachmas a kilo.

But in ancient days the entrepreneurs of Aegina had far weightier financial matters to talk about. As a cosmopolitan commercial center, Aegina minted the first European currency in 650 BC, shortly after coinage came into use in Asia Minor.

Silver statires bearing the island sea turtle emblem in honor of Poseidon stayed in circulation till AD 343 in an area more extensive than the proposed single European currency can hope to cover, throughout the Greek world to Egypt and the Black Sea, west to Gibraltar and southern Spain, where Aeginites acquired silver for the coinage.

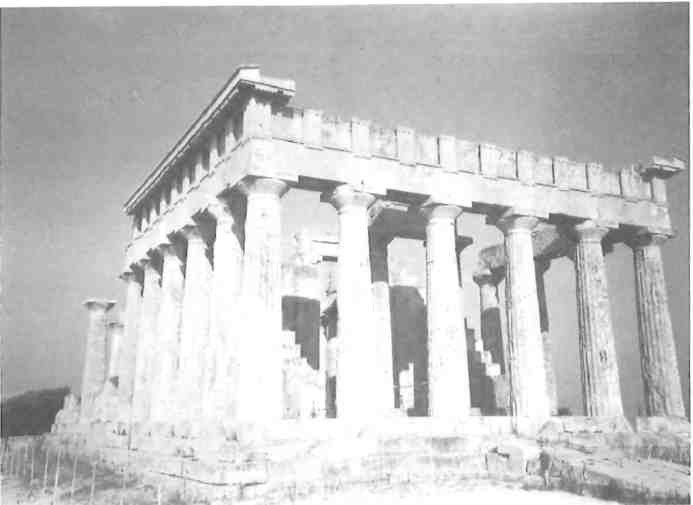

An inkling of Aegina’s past prestige is gained by the flocks of tourists visiting the magnificent remains of the temple of Aphaia built from 500-490 BC.

Perhaps the Aeginite talent for commerce and seafaring was picked up from the Phoenicians, since, following the shadowy comings and goings of Kares and Leleges, Phoenicians evidently settled here. Porphyries they used for red dye have been found near the town and the name Aegina is thought to be Phoenician for Pigeon Island.

Aegina flourished until it fell afoul of the rising ambitions of Athens. Victorious Athens blockaded Aegina for nine months till the exhausted islanders surrendered in 456. The city walls were demolished. All Aegina’s ships were handed over to Athens. Prisoners had their thumbs cut off “so they could not hold the pike.”

“From that time on, Aegina never regained its old glory,” writes author Costas Stamatis, whose account of the island has been published in English this year, “It was transformed into a holiday center where rich people and courtesans used to gather to spend their time.” So half a millennium passed in pursuing inconspicuous pleasures.

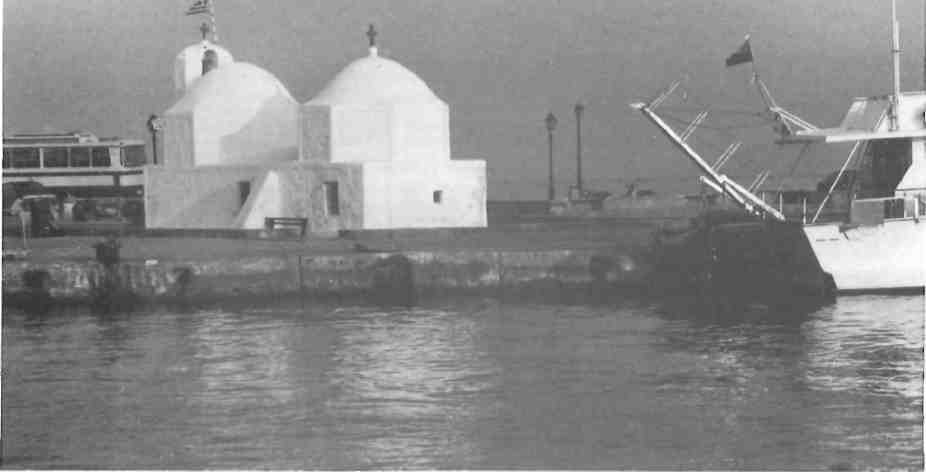

The island was converted to Christianity by Bishop Krispos, sent by St Paul, and produced a quota of saints up to the most recent canonized by the Orthodox Church, Aghios Nektarios, in 1961. Many visit Aegina on November 9 for commemorations marking the day of his death in a third-class ward in a Piraeus hospital in 1920.

There were Jewish settlers, too, and they prospered judging from the remains of two synagogues dating from the fourth to seventh centuries, and refugees from the mainland flooded over as the northern invasions began. By the fifth century, Saracen pirate raids had begun, and the capital moved to inland heights, as on other Aegean islands. Paliachora grew up on a steep rocky hillside facing south below a fort, and its overgrown remainings today may remind the visitor of a mini-Mystra.

One of the pleasures in medieval Greek history is that women appear to enliven the tedious repetition of male brutality and rapaciousness, whether Arab, Frank, Catalan or Turk. Agni, daughter of the island’s governor, Othon de Cicon in the 1290s, took Aegina as her dowry to marriage with Bonifacio of Verona in 1296. In turn their daughter, Maroula, at the age of 16, was endowed with the island for her marriage in 1317 to Alfonse Fadrigo, bastard son of Emperor Frederick II, appointed to the dukedom of Athens the same year.

Paliachora was burnt and razed but for the churches by Barbarossa in 1537. Of 9000 inhabitants, about 5000 were taken prisoners, the others massacred. A visiting French vessel the next year found not a soul on the island.

Albanians, who still have a tendency to move south, may have settled around Perdika at this point, coming from the Peloponnese.

In any case, Paliachora was rebuilt by newcomers, whoever they were, by 1570 and a monk, Daniel, installed as Archbishop Dionisios in 1576. He left after three years “to avoid becoming vain from the honors of the Aeginites.” Islanders grew strong on wheat, honey, almonds, olives and became redoubtable pirates themselves.

The Turkish Pausanias, Evlyia Tselembi, saw 100 houses and a mosque in Paliachora. in 1715. Prosperity lured Aeginites back to the seashore and the present town on the harbor was well established by 1800. Mansions, towers and houses built then indicate a high level of prosperity based on international commerce.

Aegina’s population was enriched by refugees from islands and the mainland developing less favorably and, like their neighbors on Hydra and Spetses, they were ripe and ready when the summons to revolt were delivered by representatives of the Philiki Etairia at the turn of the century.

Local hero Spyros Markellos led island revolutionaries in attacking the Turkish guard. A fleet of 68 island ships were ready for naval fray against the Ottoman fleet. Aeginite militia joined in the land wars, and the island monastery of Chryssoleontissa gave funds and food supplies to the forces.

For the war years, “Aegina was a meeting place of rich families, politicians, army officers and intellectuals from all over Greece and even from the lands of dispersion,” writes Stamatis. When Aegina town was proclaimed capital of the new state, the population surpassed 100,000. If bereft since then of glory, as well as population, Aegina for one the few times in its long history, is at least enj oying comparative peace.