It was a moderately large affair with a solid body of stripe-shirted businessmen, redolent of Old Spice and cigarillo; a sprinkling of wary cabinet ministers; a pinch of nervous diplomats; a handful of bored-looking journalists and a dash of predatory advertising men. There were a few ladies, too but I paid little attention to them because I have long since discovered that women who attend business lunches have invariably left their sex appeal behind at the office.

The speaker was a Eurocrat from Brussels whose subject was what Greece has to do to become an equal partner in an integrated Europe. After the waiters had served us icecold water and white wine, I settled down for the interminable wait before the first course and slowly demolished my bread roll. Almost everybody around me was chatting excitedly, describing summer vacations in exotic parts or recounting hilarious misadventures in Loutraki or Platamonas. The only person who was saying nothing was a placid-looking individual on my left who smiled at me when I turned to look at him.

We introduced ourselves and I discovered his name was Platon Kaloperasakias. When I asked him what he did, he said:

“Nothing. I’ve never done a stroke of work in my life and I trust I won’t have to, ever.” I took an instant liking to him.

There are many people in that happy state but I had yet to meet someone who admitted to it so readily. Usually, they say: “Oh, a little bit of this and a little bit of that,” or “I work on odd projects from time to time,” or “I’m a consultant of sorts.”

“You must have a private source of income,” I ventured.

“Yes,” he said. “I married a rich wife.” I liked him even more.

“How come you’re attending a business lunch, then?”

“Oh, the speaker’s a friend of my brother-in-law’s and as he’s having him for dinner tonight I thought I might as well hear his speech and have something to talk about when we meet. A waste of time, really, because I can guess what he’s going to say and I can bet you anything you like he’ll miss the whole point about Greece and its future.”

“Oh, yes? And what’s that?” I asked.

“Well, he’ll say we have to work hard and make sacrifices and tighten our belts and . reduce public spending and bring down inflation and create the right climate for investments and all that sort of things. More or less the same things Mitsotakis said in his Salonica speech. Of course, the mistake Mitsotakis made there was to put the blame on the socialists for Greece’s economic mess. That’s not true at all.”

“You think Papandreou’s policies were the right ones?”

“They may have been wrong in terms of western theory, but they werebang on as far as the Greek character was concerned. Hence the inan’s tremendous popularity.” I looked nonplussed.

“Look here, my friend,” Kaloperasakias went on, “for the first time in the history of modern Greece, Papandreou created conditions by which the great majority of Greeks could do as little work as possible, or no work at all, and be paid handsomely for it. Not temporarily, mind you, but forever, with no possibility of being sacked and with the prospect of getting pensions from several different sources. “For the ordinary Greek, this was the fulfilment of his very raison d’etre, a nirvana from which he is being rudely shaken out of by the EC and Mitsotakis.

You’ve heard of the Protestant work ethic: Well, that doesn’t apply to us Greeks. We’re not Protestants for one thing and nowhere in our religion does it say we have to work. It says we must fear God and love our neighbor but it doesn’t say we have to dig in a field from dawn to dusk or work in an office from nine to five.

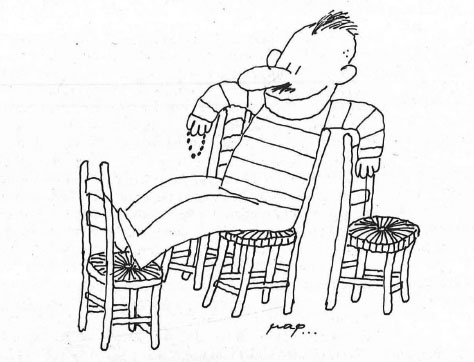

“Greeks firmly believe in the nonwork ethic and if they have to work to .earn a living, they will do so with the greatest reluctance and an even greater repugnance, ever looking for a chance to escape from the drudgery so they can sit back and enjoy the finer things of life, like sitting in a cafe, playing backgammon or cards, eating out and having clandestine love affairs, preferably two or even three at a time.”

“Now, surely that’s an exaggeration,”

I protested, “there are lots of people in this country who work hard … “

“Ah, yes,” he interrupted.

“But only when they’re working for themselves. If you ever come across a hardworking employee I’ll bet you’ll find him to be eiti}er slightly retarded or else he’s stealing his employers blind. And what do these hard workers do as soon as they’ve made a small pile? Sit in a cafe, play cards, eat out and support one or two mistresses. Paradis a la Grecque!”

I laughed. “What about the Greeks who make good abroad?” I suggested.

“Have they abandoned the Greek non-work ethic and adopted the Protestant way of life?”

“They’re the exceptions,” Kaloperasakias said, dismissively.

“That’s why they left Greece in the first place. For them, working hard is what gives them their kicks and they couldn’t do it in Greece because everybody would think they were retarded or were stealing somebody blind. So they went abroad, to America, Australia or elsewhere and basked in the sunshine of public approval as hard workers, completely attuned to the Protestant ethic. Exceptions that prove the rule.”

“So what’s to become of us?” I asked, playing along with him.

“How can we take our place in an integrated Europe if we don’t change our character?”

“It’s simple,” Kaloperasakias said.

“We don’t have to change our character at all. The West Europeans will come down in droves and buy out our businesses, our banks, our hotels, our public utilities and our industries, work hard to bring Greece in line with the rich EC countries and, since they can’t throw us out of our own country, they will perforce have to share the eventual prosperity with us and then we shall all be able to sit in cafes, play cards, eat out and have mistresses – the Greek dream come true.

“Am I not right?”

“From your mouth to God’s ear,” I said, solemnly.