Shaped like a pregnant guppy swimming away from Anatolia, the isle of Samos is a geographical continuation of the adjacent mainland, formed of the same schist strata and cloaked by the same lush vegetation as on Mount Mycale across the water. At some point during the later Ice Ages, earthquakes sundered the island from Asia Minor, leaving the straits between Mycale and present-day Pithagorio as the narrowest separation between modern Greek and Turkish territories. The ancient name Eftastadio Poros (Seven Stadia Straits) was more literal than poetic.

Samos has always figured among the most fabled, wealthiest and historically significant Aegean islands, though it is a’ reputation grounded more firmly in the distant past than in recent years, and of which there is little surviving evidence at first glance.

Originally colonized from various sources around the Mediterranean before 900 BC, Samos reached the apex of its fame and glory during the sixth century under the tyrant Polycrates. His capital, strategically opposite Mycale, was enriched by the proceeds of both conventional sea trade (including piracy) and offerings brought to the neighboring Temple of Hera, the largest in the ancient world; his court hosted some of the most illustrious personalities of the age, including mathematician-philosopher Pythagoras and the astronomer Aristarchos. Herodotus devoted large portions of his Histories to the monuments, personalities and episodes of the city, including Polycrates’ eventual entrapment and execution by the Persians.

The price of liberation from the Persian yoke over the next two centuries was domination first by Athens during her Golden Age, and further subservience to distant centres of power during the Hellenistic and Roman eras. Owing to its position in the east central Aegean, it was frequently a hapless doormat for belligerent armies or navies bound in various directions; relative stability and prosperity was not restored until the sixth century, when Samos was constituted as its own theme (administrative division) within the Byzantine empire, a status that would endure uninterruptedly until 1080 and sporadically thereafter.

During the closing decades of the 15th century, raiding Turkish pirates slaughtered virtually the entire popula-tion of the island except, it is claimed, two or three inaccessible inland hamlets. Samos remained uninhabited for nearly 100 years until a storm forced the Ottoman Admiral Kilitch Pasha to anchor offshore in 1562. Impressed by the beauty and fertility of the deserted island, he obtained permission from the sultan to repopulate it, with a grant of

special privileges to the new inhabitants and a ban on any Turkish Moslem settlement. (The locals claim, probably correctly, that alone of all the east Aegean islands, there has never been a mosque on Samos).

The special concessions lapsed with the death of the admiral, and during the War of Independence the islanders fought fiercely under Lykourgos Logothetis on behalf of the cause, repulsing overwhelming Turkish forces in the summer of 1824, including a fleet decimated in the straits off Mount Mycale. By 1830, however, the Great Powers had returned Samos to Ottoman rule, though under a special arrangement known as the Iyimonia, the island was ruled under a Christian prince responsible to the sultan, and Turkish occupation was again banned. The last prince was assassinated, and union with Greece accomplished in 1912, in the context of the First Balkan War, though Samos endured a particularly bitter 1941-1944 occupation by Aegean standards, with an active guerrilla movement in the mountains and bloody reprisals by the Italians, and later the Germans, in response.

These excesses of undiluted patriotism notwithstanding, the key to so much of modern Samos’ character lies in the 16th century resettlement. Village names – Mytilinii (the Mytilinotes), Arvanites (the Albanians), Vourliotes (those from Vourla in Asia Minor), and a host of others in the nominative plural which seem to be clan names or surnames – betray the origins and antecedents of the contemporary islanders. One may surmise that Kilitch Pasha at the time didn’t inquire too closely into the past of his volunteers; in a word, Samos became the Australia of the Ottoman empire for its Greek Orthodox subjects. To carry the analogy further, it is a place rich in scenic beauty, natural marvels and prodigies, chthonic spirits and ancient associations and culture, but pervaded in the human sphere by deracination and anomie, with a complete discontinuity between the present and even so relatively close a past as the Byzantine era.

Then again, a visiting Cypriot friend found both -the terrain and the people highly reminiscent of Cyprus; the same jungly summer humidity promoting both lush growth and a certain Levantine languor, the same androgynous eight-year-old Neros who mature into slightly epicene, grizzled, well-padded men. Neighboring islanders cordially (or less than) detest them; for the Doric-aboriginal Ikarians, kolosamiotis (asshole Samiot) is almost a redundancy.

There is little genuine Samian music or dance, the oftcited Samiotissa to the contrary (composed by an off-islander). Ditto for the cuisine; Samian wine of Byronic fame is chemicallaced and vastly overrated, with little or no relation to ancient precedents. It is, in fact, the result of a French ‘missionary’ effort in the 1880s, until which time wine-making had been neglected since the medieval disaster. Hima or bulk wine is just about nonexistent, the tyranny of the vintners’ cooperative being absolute, unless you have friends who have squirrelled away some grapes for home use. The co-op’s pop-top white plonk, or the Fokianos rose, are both more drinkable and cheaper than the cork-sealed Samaina, but none are especially recommendable.

Meat is better, if a bit exotic; town butchers stuff excellent, unheralded sausages, some of the best I have tasted in Greece, and goat chops are an effective substitute for the scrawny imported paidakia. Like the Ikarians next door, the Samiots have a curious aversion to sheep and sheep products. A single dairy in Hora exploits the milk of what seems to be the lone flock of ewes; another in Ano Vathy relies on a similarly unique herd of cows. Spring and autumn seafood is plentiful, especially when compared to the more central, and fished-out, Aegean islands, but not as abundant or cheap as on Limnos, Lesbos or Chios; they are first in line, so to speak, for the rich bounty pouring out of the Dardanelles, leaving remoter Samos with the leavings.

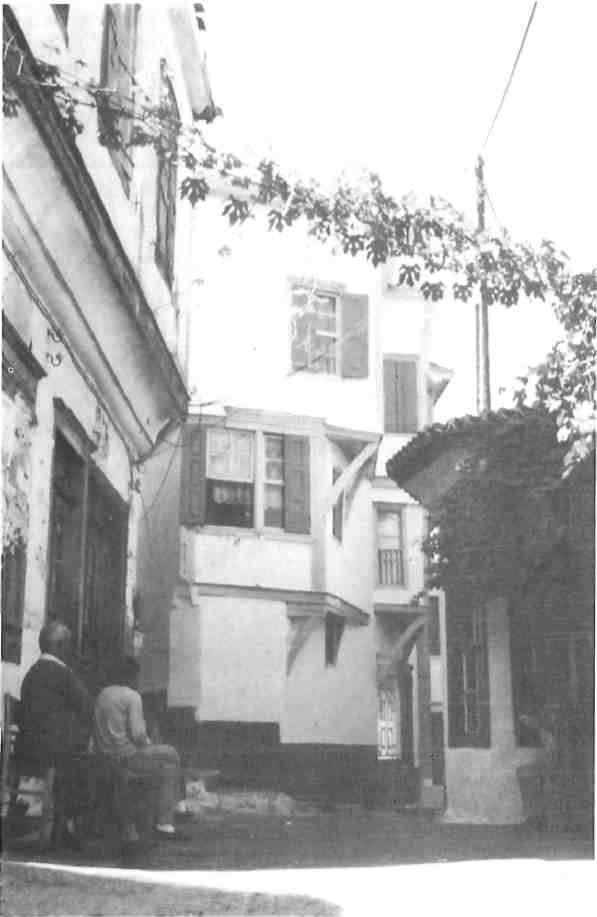

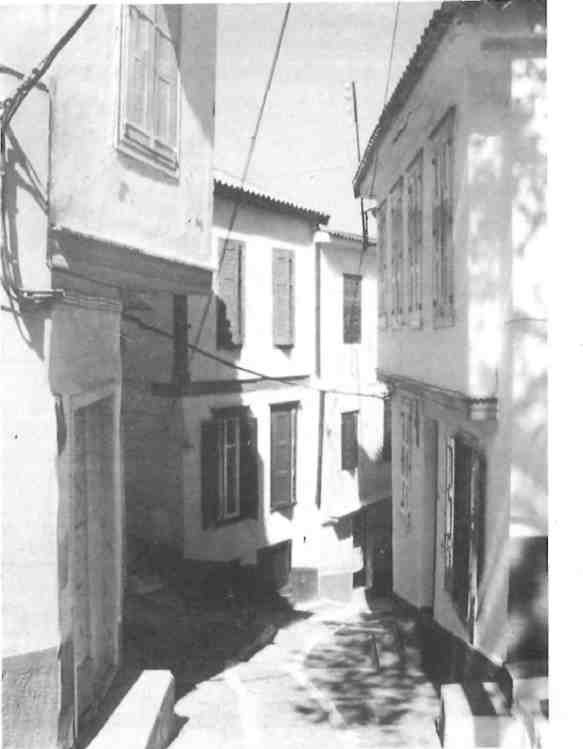

The vernacular architecture is a hodgepodge of styles, much of it, as throughout the east Aegean, mirroring that on the Anatolian mainland opposite, in this case Kusadasi. Thick-walled, stone dwellings predominate on the thinly forested, hot-summer south flank of the island, but on north-facing slopes most houses are tsatmas, a fragile lath-and-plaster concoction which requires constant maintenance. Peren-nially rotting shutters and doors, in theory brightly painted, keep the handful of marangi (joiners) in steady work, but ironically on such a forested island, the wood for the jobs now comes from far-away Sweden, the precious local trees being reserved for caique hulls.

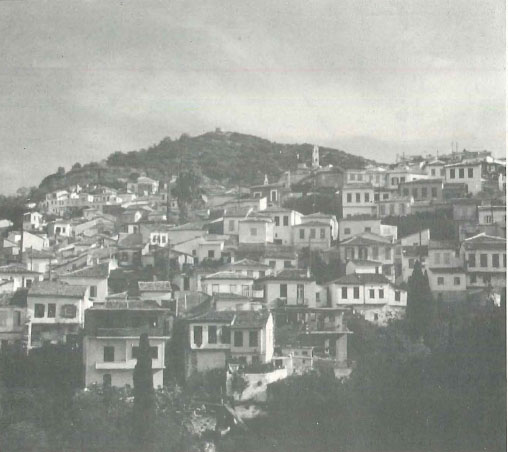

Samos is perhaps the most countrified of the northeastern Greek islands, with just under half the population of 25,000 in the two main towns. Representation of the University of the Aegean is token, with just a maths faculty in Karlovassi and a new nursing school in Vathy. The last surviving cinema became yet another soupermarket last year, and there is no decent, permanent concert or exhibition venue. The central park, recently and rather brutally renovated, is the smallest and shabbiest between Rhodes and Mytilini, an appropriate metaphor for the lack of civic spirit. You don’t come to Samos for a dose of culture.

Who does come to Samos, then, and why? Before the early 1980s, very few tourists indeed. On my first visit to the island, it had less than 10,000 guest beds, and the clientele was an international cocktail, including a fair sprinkling of backpacking overlanders transiting between Turkey and Greece, The boom began in the latter years of the decade, with 30,000 hotels slots at last count – not quite another Corfu or Crete yet, but edging into the Greek Top Ten.

Nordics predominate, with a leavening of Italians arriving on the Minoan Lines ferries from Ancona. Scandinavians and Dutch congregate in the arid, scrubby setting of Pithagorio, content to bake in the sun or pop over to Kusadassi, while Swiss and Germans favor Kokkari and Karlovasi, both overawed by dramatic, often cloud-capped mountains looking like they have just stepped off a Caspar David Friedrich canvas; nature excursions into this quintessentially Romantic landscape are accordingly popular. The staid (cynics say square) social scene is firmly honeymoon, or second honeymoon-oriented; even the gays come in polite couples. It is a far cry from the occasionally outrageous singles profile of Paros or Ios, and the lack of an official campsite on such a large island and the often astounding menu prices tells you exactly what sort of trade the authorities are expecting.

The overnight mushrooming in tourism has caught the islanders poorly equipped to adjust to it gracefully; there is not the decades of experience, as in more cosmopolitan resorts, to lend a polish to the performance. Managerial barnyard manners displayed in the new-wave, chrome-trimmed-and-track-lit interiors that the island’s nouveau riche sensibilities (and visitor tastes) demand, may bring you up short, to say the least.

More ominously, the combination of increased visitor traffic and dense, flammable vegetation could be a recipe for continuing disaster. Three fires in 1990 ravaged the forests between Kokkari, Vathy, Mavratzeoi and Hora, essentially the eastern third of the island’s greenery, and in 1991 there were multiple blazes between Vlamari and Possidonio further east. While the con-spiracy theorists have had a field day as usual, the connection between tourism and arsonists’ motives seems indirect but sound. Whether the firebugs are Turks-jealous of the island’s new-found fortune, rival taverna owners deter-mined to ruin each other’s backdrop, inheritance feuds or an attempt to devalue an overpriced plot of land, the end result will be the same – foreigners will stop coming to a denuded landscape that is not as promised in the glossy brochures, and the Samiots might be forced to contemplate their previous professional options: tobacco, hemp (for birdseed and twine, of course), or emigration.

Unless you arrive by air, most Samian visits begin at the port of Vathy, founded after 1830 as the new island capital, superseding inland Hora. It lines the sloping northeast flank of a penetrating bay (hence Vathi-pou-vromaei (Vathy-that-stinks) is a cognomen among the natives of rival Karlovassi at the opposite end of Samos.

Your first order of business, especially if time is short, should be the Archaeological Museum, among the best provincial ones in Greece. The collection outgrew the old Paskallion building some years ago, but the opening of the new wing across the way was twice delayed since its star exhibit, a majestic, five-metre-tall Kouros, was discovered out at the Heraion in installments: first the head and torso, then the thighs, finally the forelegs, each time compelling the builders to raise the roof of the alcove planned to house it. This largest free-standing effigy in the Greek world, despite being dedicated to Apollo, was found along with a devotional mirror of Hera (one of only two unearthed in Greece), and many votive offerings of Egyptian design, proving trade and pilgrimage links between Samos and the Nile Delta going back to the eighth century BC. (The only other shrines to Hera in modern Greece are the ninth-century one at Perahora on the Gulf of Corinth and the even older Argive Heraion).

The German Archaeological Institute controls the digs at the Samian Heraion, and also financed the con-struction of the new wing and renovation of the imposing neoclassical Paskallion, now a treasure trove of small, elaborate, non-marble objects from the Archaic and Geometric periods; classical Samos was in decline. It is the largest provincial Greek collection of finds from Egypt and the Middle East, and as such has a distinctly exotic cast.

The Egypt-Samos link is further demonstrated by statuettes of a hippo, a female dancer in Nilotic dress, Horus-as-falcon, an Osiris figurine, and two mirrors sacred to Mut, from a workshop in Upper Egypt; Mut was identified with Hera just as Aegean Artemis became syncretized with Anatolian Cybele. Among Mesopotamian/Anatolian items, it is worth mentioning a case of ivory carvings: Perseus and Medusa in relief, a kneeling, intact mini-kouros, and a pouncing lion. There is another lion figurine nearby with some model houses and a rhyton (drinking horn) ending in a bull’s head.

Native Samian work is represented by some very early (eighth-century) terra-cotta, unsophisticated when compared to later, orientalized work such as faience-inlaid Anubis and Horis figures. A section of rare wood sculpture at the top of the stairs includes an utterly African mother and child. The most famous local items are a dozen-odd bronze griffin-heads, mostly from the seventh century; Samos was the main centre of production. Mounted on the edge of the hammered or cast phialai, they had an apotropaic effect.

Otherwise Vathy, divided into harbor and hill quarters, is very much a mixed bag. The waterfront, currently getting a facelift, consists of a dull succession of mostly mediocre tavernas and redundant travel agencies; a conspicuous oddity is the shuttered Catholic church near the ferry dock, labelled in Latin Ecciesia Catolica. This is a by-product of the French viticulture crusade; an order of nuns ran a school here for well on a century, before giving up in 1974, leaving one forlorn family of converts somewhere in town.

It is difficult to fathom the wisdom behind the new marina being dredged near the head of the bay. Vathy is a miserable anchorage for small craft, fully exposed to the prevailing northerly swell, and no yacht skipper in their right mind will forego the sheltered south flank of the island if they can help it. The new port will only aggravate the local aroma problem with emptying bilges adding to the untreated sewage pumped into the bay by the town’s luxury hotels. What the area really needed was a wider coast road; traffic signals; a shuttle bus service; a proper sewage system, and – further afield – a bypass road to relieve perennially congested Pithagorio. But then, this is Greece.

The main agora, one street inland, is running at 70 percent speed, with many storefronts vacant due to disputes over exorbitant rent demands or intra-family feuds. Still, not all of its character has been sacrificed, and there are yet businesses providing unique and necessary services – a glazier, a coffee grinder, a loukoumadesfryer, an excellent bakery – tucked in between the one-hour photo labs and beachwear boutiques. Doyen of the curiosity shops is Mihalis Stavrinos1 antique business, where, if you are feeling flush, you can invest in a limited-edition YiannisTsarouhis print or rescue a rare 9th-century engraving from the silverfish. Farther back is the characterful neighborhood of Prosfiyika, whose refugee cottages and mirror-image duplexes look positively inviting compared to some of what is built lately, lining cobbled streets with predictably nostalgic names from Asia Minor.

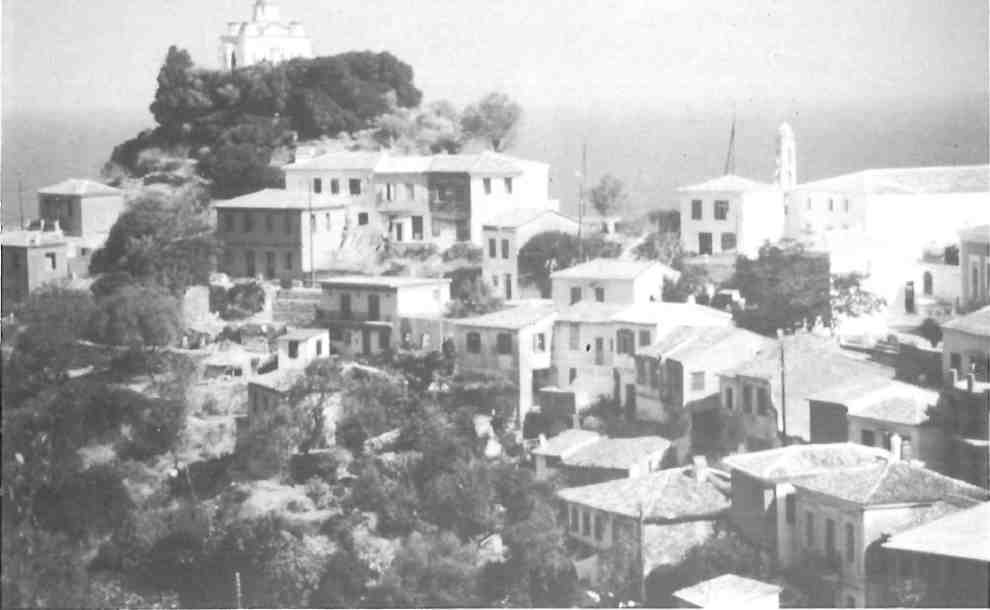

Things improve more up in Ano Vathy, 150 metres above sea level, a preserved community of tottering, tile-roofed houses that is the goal of many a day-stroller. Two churches merit a visit; the tiny, central chapel of Aghios Athanasios, with its altarscreen and naive frescoes, and the multi-domed 18th century Aghios Nikolaos, out by itself in a badly executed park/playground. Nightlife is nil, however; despite two hotels at the outskirts, there are no tavernas or ouzeries within the village.

From here it is easy to continue east and inland to Vlamari, a vast elevated kambos with vineyards, flanked north and south by the appealing hamlets of Kamara and Aghia Zoni. The latter village takes its name from an adjacent monastery with the most outrageously landscaped courtyard on the island. Beside the monastery a track, then a trail, leads down to the hidden bay of Megali Lakka, where a single family has come year after year to tend the chapel of Aghios Nikolaos and occupy a kalyva in summer.

Here too, a young Dutch archaeologist was strolling in the shallows one day when she stubbed her toe on something metallic. Scrabbling in the sand, she unearthed a bronze urn containing twenty-odd gold Byzantine coins from the sixth century. Upon handing it over to the local museum she duly received her finder’s reward, but in a lapse of curatorial judgment the coins were foolishly sent to Athens for cleaning and were never seen or heard of again. (Now when Samiots want something of the sort attended to, they prevail upon the German excavators at the Heraion to do it for them.)

Kamara has two good tavernas; beyond these a path and dirt road sputter respectively to Zoodohou Pighis monastery, spectacularly set (along with the inevitable military installations) on a promontory overlooking Turkey, and the tiny fishermen’s anchorage of Mourtia, lent an exotic touch by a palm tree. From Kamara you can also hike, in the course of a long afternoon, by track and trail around Mount Thios back to the harbor, passing along the way magnificent views of Anatolia, and the turn-off to Aghia Paraskevi, another tiny port with a good taverna, You also walk just under Profitis Ilias, a tiny white capsule visible from many points of Vathy Bay; beyond it, along the ridgeline of Thios, steam issues from vents in the rock.

Points south of the capital are better known and more geared up for tourism. Psili Ammos, a small sandy bay featured as a destination on virtually every tour operator’s signboard, is saturated to bursting in season; you can swim out to an islet, but currents are surprisingly strong. The visitor overflow seems set to be transferred to Mykale beach, the immense stretch of pebbles just to the west, for years pristine but now dotted with building sites.

Flamingoes used to stop over in spring at the lagoon behind, but in the past two years they failed to show up. Most traffic, however, heads for Pithagorio, the island’s premier resort, known until 1955 as Tigani (Frying Pan) – in mid-summer you will learn why. The small harbor, fitting more or less into the confines of Polycrates’ ancient port, is devoted today entirely to pleasure craft and bar/cafes; there are some decent hotels if you can slip in between the tour groups, but you are best advised to eat in nearby Hora (of which below). Samos’ only attempt at a castle, the 19th-century Logothetis pyrgos, dominates the town, which on inspection proves to encompass vast areas of archaeological excavations. For this was the core of Polycrates’ capital; the most obvious monuments are the Evpalinos Tunnel, an aqueduct bored into the hills behind, and the later Roman baths on the seashore on the way to Potokaki, the cluster of hotels at the end of the airport runways.

Dwarfing Potokaki proper, and destined to confound archaeologists of future eras, is the huge Doryssa Bay resort, meticulously concocted as a fake village, with ‘no two buildings alike, centered around a plateia with a kafenio (expensive) and a woodworking shop whose sole commission is to cut shutters and cabinets for the guest units. The beach, the Pithagorio area’s best by default, stretches for three kilometres west from the baths; the water, as everywhere on this coast, is clear but surprisingly cold all year, owing not just to the aforementioned currents but to quantities of fresh water pouring into the sea, from streams and subterranean springs. On the bottom sea, stars, sole and other fish, seem as oblivious as the sunbathers to the manoeuvres of descending planes.

The main circum-island road presses on to Hora, a linear, scruffy village that was Samos’ medieval capital, and, judging from a tiny acropolis, a place of some importance before, as the most outlying fortified settlement of the ancient city. It is easily the liveliest -read noisiest – of the southeastern villages, a bedroom community for the officers at the nearby army camps and those involved in the nearby tourist industry, but at least the food is good; virtually any of the four tavernas will serve you a better, cheaper meal than you will get in Pithagorio. Mytilini, four kilometres further inland, seems amorphously big and working-class; the plateia has some atmospheric cafes, a new taverna and a good antique store just off it, but the Paleontological Museum above the post office is a distinctly minority taste.

Hora overlooks a vast plain of olives and citrus curling around the airport to the sea; somewhere under the runway ran the Sacred Way linking Polycrates’ capital with the Heraion, the massive shrine of the Mother Goddess, of which a mere single column stands today. The modern resort of Ireon nearby is a grid of dusty streets perhaps five blocks long by three deep, its only advantage over Pithagorio being the opportunity to dive off the verandas of various tavernas and pubs directly onto a poor beach. The closest real village is Mili, reputed to have the balmiest winter climate on the island, with Pagondas well above it, graced by a fine square and a barn-like washhouse at the edge of town.

Inland from Hora, there are turn-offs to the monastery of Timiou Stav-rou, the island’s most important, with a festival on 14 September, and Mavratzeoi, a pottery village famous for its koupes tou Pithagora (Pithagoras cups) designed to ‘pee’ on the user’s lap if he overfills it. More conventional and usable kiln items are available in Koumaradeoi, astride the main route, just before Pirgos, lost in pine forests and focus of Samos honey production. Here side roads lead north to Arvanites, highest village on the island, where the old boys in the cafe still swap andartiko stories from the last war, or south to Spathareoi, set on a natural balcony overlooking the Aegean – as well as rugged and beautiful coastal terrain glimpsed for the first and last time by most people on the airplane in. To get to the tiny anchorages and beaches by vehicle, you will have to follow the gorge beginning at Pirgos down through Koutsi “The Paradise with the 17 Plane Trees”. I haven’t counted them but the exohiko kendro and the gushing spring here are both excellent) to the junction for Koumeika and Skoureika. Below Koumeika stretches the pebbly bay of Ballos, with a handful of good tavernas; Skoureika is the gateway to the even remoter outposts.

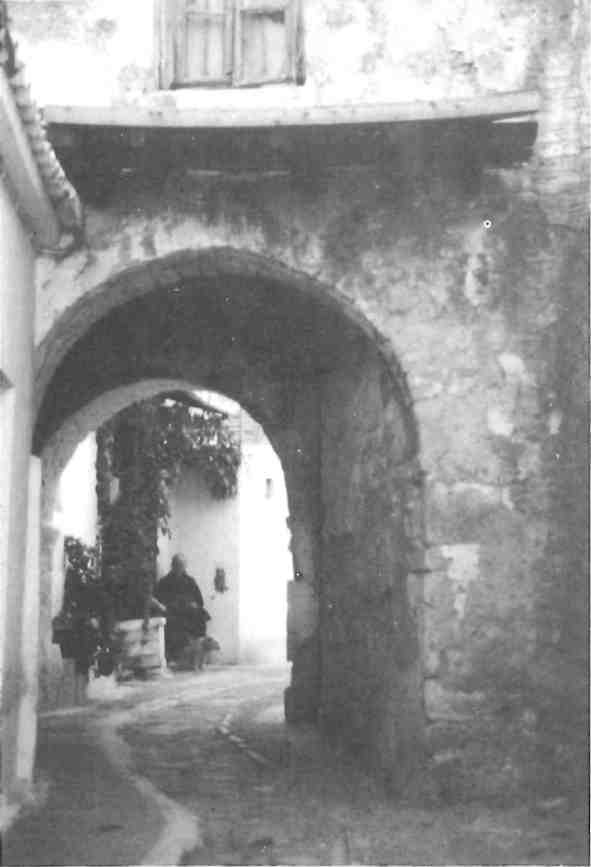

From Koumeika a perfectly manageable dirt road shortcuts through Velanidia to Ormos Marathokambos, a growing resort that would have been a more logical candidate for a new yacht harbor. From the workaday port, with the occasional boatbuilder on view, bricks (of all things) are sporadically shipped to the Dodecanese. The hill settlement of Marathokambos has retained barely 10 percent of its former population of 4000 but the unique domestic architecture – included arched-over streets – remains. A path, with a spring and watercress halfway along, joins it with Votsalakia beach, the expanse of gravel and sand west of Ormos that is the island’s fastest growing resort. It cannot offer the nightlife or variety of facilities that Pithagorio, Vathy or Kokkari do, so it seems to have emphasized family, self-catering accommodation; accordingly tavernas are bland and overpriced.

Mount Kerkis (Kerketevs), presiding genius of Samos’ west end, looms overhead and makes for a good day or two’s excursion. In its foothills charcoal-burners still potter about, emerging like blackened trolls from behind their lightly smoking pyramids. The classical ascent, briefly track but trail thereafter, goes via the convent of Evangelistria, where one of the four nuns will fortify you with a shot of ouzo for the final push up to the peak. Just below, on this side, is the chapel of Profitis lUas, and a bit higher – after a wet winter – a much-appreciated spring. On the north side of the summit is the spot where an Olympic Aviation STOL craft crashed on 3 August, 1989, with the loss of all 34 aboard – a grim blot on Olympic’s excellent safety record and a tragedy which the islanders are still reluctant to discuss.

Come down from the mountain early enough – it is a five-to-six hour round-trip pull – and you can reward yourself with a swim at Psili Aminos, beyond the Votsalakia asphalt’s end and vastly superior to its namesake at the opposite end of the island. Few outsiders venture beyond, as the road deteriorates both with very much of an end-of-the-line feel, staring out to Ikaria and down to tiny harbor at Aghios Kirikos.

However, the main reason to come out here is to pick up the wonderful ‘two-hour trail across wild gorges and through still-unburned pine and arbutus forest down to Megalo Seitani, Samos’ most beautiful and unspoiled beach. It is supposedly the linchpin of a controversial monk seal reserve, set up because of – or despite – the efforts of two Greenpeace activists in the late 1970s, an Englishman and a Swiss woman who managed to thoroughly antagonize the islanders and eventually got themselves chucked out. The locals doubtless concluded that anyone equipped with sophisticated binoculars and Zodiac dinghies, and yet whose post-hippie garb flaunted their obvious penury, had to be dangerous spies in the pay of a foreign power. The Englishman, William Johnson, went on to write a rather testy book on the episode, The Monk Seal Conspiracy, (1988, Heretic Books Ltd) while the Swiss lady was eventually rehabilitated to the extent of buying a house in one of the Samian hill villages.

That said, you are exceedingly unlikely to see any seals even at this remote spot, as they are shy creatures and the handful of motorboats loaded with Greek bathers that rear up here in season will be sufficient to scare them off. Seitani is a clothing-optional zone, and if you raise any eyebrows you might just point out that,by the terms of the reserve’s creation, motorised transport is illegal – as are the half dozen bungalows at one end of the bay. Mikro Seitani, 45 minutes further east among the half-abandoned olive terraces, is a small, sculpted cove, and another favorite place to shuck one’s clothes. The sea from here on is surprisingly warm -it is the first strand on the north coast where people venture in by May.

You will emerge, after another like period of walking, at Potami, a generous crescent-shaped bay flanked by bizarre rock formations and to the east, a hideous post-modern chapel of Aghios Nikolaos which a visiting friend from California, in a moment of irreverent wit, aptly dubbed the “Panayia Tacoou Bellou.” Far better in the way of ecclesiastical architecture is the sign-posted tenth-century church of the Transfiguration, just inland up the river which gives the beach its name. Any frescoes are long gone, but the soaring design, rather higher than it is broad, is appealing.

If you continue upstream for awhile, you will eventually reach a spot which some locals have nicknamed Thailand, after the dangling lianas and the cul-de-sac where rock walls bar further progress on foot. Here you must dive into heart-stoppingly icy water to swim several hundred metres through the rock gallery to a natural basin where a small waterfall plunges. Most of the time you cannot touch bottom, but when you can, beware the freshwater crabs scuttling about and the eels trapped here in dry years, unable to escape out to sea again atter spawning.

It is a dull road walk back to Karlovassi along the coast road; far better, if time permits, to follow the hour-and-a-half path over the cliffs to Paleo (Ano) Karlovassi, passing en route the little cave church of Aghios Antonis. Here, an indefinite number of years ago, local legend of the Circe-and-swine variety asserts that a young man was bewitched and emerged after a delay of two weeks nearly bereft of his reason; today it seems disappointingly ordinary, in the throes of restoration.

Paleo Karlovassi, full of German-speakers renting many of the fine old houses long-term, occupies both banks of a steep ravine, the easterly one culminating in the chapel-hill of Aghia Triada. Some nights it blazes with a thousand candles, though empty, as if in anticipation of a witch’s coven; if you stumble up here after a drinking session at the harbor (as 1 once did) it will scare you witless. The port, however you reach it. is appealingly peaceful compared to Vathy or Pithagorio; off to one side is a caique-building enclave, near the jetty with its clutch of shipping agencies and warehouses. In summer, a line of traditional tavernas and new-style pvtb-ouzeries do a brisk trade, but mosllv ίο Greeks – the hotels and visitor services which sprung up one street behind a few years back mostly go begging, the ranks of foreign tourists never really having materialized.

There are two more quarters to Karlovassi: Messaio, curled around a hill a kilometre back from the shore, the intervening space dotted with several giant churches sporting blue-and-white domes, and occasionally ugly Neo, founded as a refugee community on the far side of the riverbed. With a vast floodplain contrasting with the cramped situations of Vathy and Pithagorio, the town took advantage of the space to sprawl unaesthetically, and a leather-goods industry briefly thrived. This had collapsed by the last war, however, and now the place seems overbuilt and hollow, with an entire shoreline district of imposing but derelict tanneries, warehouses and mansions. Today they are worthless, though tomorrow the echoing brick and stone walls may serve as the ultimate disco, boutique or who-knows-what. Thus far there is but an ouzerie or two exploiting the still-in-process waterfront.

Moving east from Karlovassi along the coast, Kontakeika and its shore annex, Aghios Dimitrios, are the first places you would think to stop in; the former for its views of saddle-shaped Kerkis and arguably the finest sunsets on the island, the latter for its good but unpublicized fish tavernas. Beyond here sheer cliffs closely hem in the road – only recently resurfaced after nine years under construction – until the landscape relents somewhat at Aghios Konstantinos. A rare case of stillborn development, “Aghios” (as the bus conductors habitually bawl it out) lacks the ingredients necessary to be a successful coastal resort; usable beaches are too distant and the surf-battered esplanade, despite attempts at renovation, is as dishevelled as Karlovassi’s. Partly for this reason the area is a favorite of expatriates; Ano Aghios, just uphill, and the wine village of Ambelos host large numbers of foreigners buying or renting houses. Only Platanakia, an eastern suburb of Aghios, sees much tourist traffic in the rooms and tavernas under its overarching canopy of plane trees.

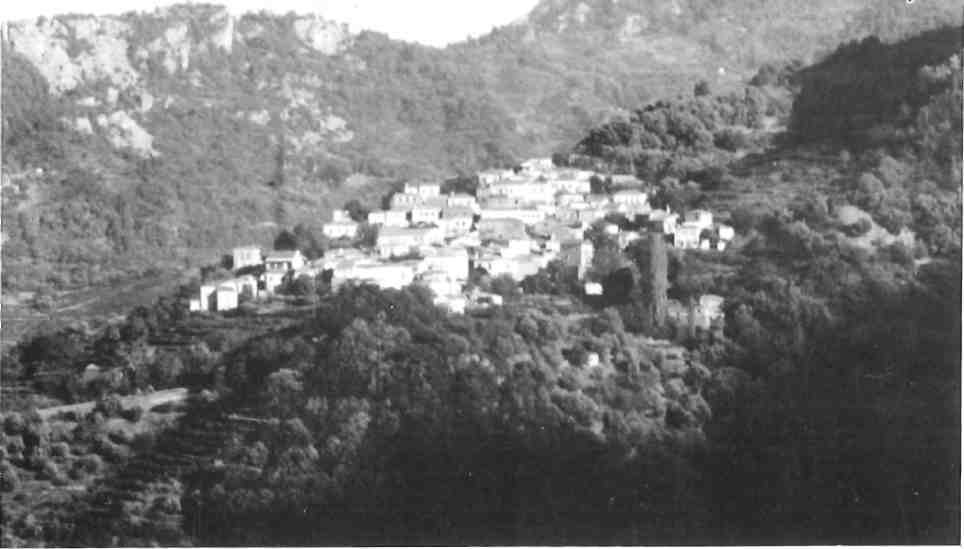

Inland up the valley threaded by the tree-feeding stream leads to the most enchanting landscape on the island, a Iushly vegetated ridge system sheltering the villages of Stavrinides, Manolates and Vourliotes, connected with each other, Aghios and Kokkari by a fine path system. Stavrinides is the least favored, Manolates the most spectacularly set, with the vine terraces and cypresses spread below you as in a Renaissance painting. Foreign exiles congregate here, too, but it takes a stern will to outlast the dank winters. Manolates is also the most popular jumpoff point for ascents of Mount Ambelos overhead, the island’s second summit, blessed with fine views east to Turkey – and some enigmatic military telecom reflectors.

Vourliotes is the largest and most thriving of this cluster, with burgeoning orchards and a photogenic plateia where one of the tavernas – in an exception to the horrible-wine rule-sells expensive but delicious moskhato, suitable as a dessert drink. Just east lies the monastery of Vrondiani, the island’s oldest but now disestablished and taken over by the army, who have made some horrendous architectural desecrations. More happily, it is the focus of the 8 September Festival of the Virgin’s Birthday, and takes its name (Thunderer) from the local lore that either the week preceding or following the date will be unseasonably stormy; each of my three Septembers here had borne this out.

Below, three of Samos’ most picturesque shingle beaches line the shore between Aghios and Kokkari. Tzabou and Lemonakia are fresh-*water-less, and the latter is being defaced by a new hotel, but Tzamadou (rhymes with Xanadu) has long featured in virtually every tourist poster of the island and has a spring exploited by the standing colony of summer campers. Their previous mountains of trash have been cleaned up, the beach amenities spruced up, but it is still the most trendy strand on the island; its west end, by tacit consensus, is naturist.

Kokkari, a 30-to-40-minute walk from Tzamadou and Lemonakia, is the one place that prompts nostalgia among Samian veterans. While lower Vathy and Pithagorio had little beauty to sacrifice, much has been irrevocably lost here. The town plan, covering two knolls behind twin headlands, still exists, but even this is under threat as the fishing port is having an outsize breakwater added, which hopefully will not become a pretext for another ill-advised yacht harbor. Amazingly, a family of three still doggedly untangles its fishnets on the quay, but in general identity has been altered beyond recognition. Like so many Greek island coastal villages, it is now an elegant stage set, admittedly with some good, if expensive, tavernas better than anything in Pithagorio, expanding slowly inland over the former onion fields that gave the place its name. With exposed, uncomfortably rocky beaches close by, buffeted by near-constant winds, it seems an unlikely victim of gentrification, though its Germanic promoters seem to have made a virtue of necessity by developing it as a highly successful windsurfing centre.

From here the road back to Vathy is uneventful, your arrival announced by the thick pines of the industrial suburb of Malagari, where there is a winter ferry dock for when the main one is unusable. As you enter the west end of town, you pass two priapic monuments: the Disco Xenon, with its incredibly bad-taste fountain puff, and a neoclassical mansion, formerly a bordello, alongside Samos’ main road junction. It, like a great deal of the island’s real estate, is now for sale.