Seven nautical miles off Anatolia, and just south of the Dardanelles, Tenedos (Bozcaada in Turkish) is far less militarized than Imvros and architecturally more of a piece. It is toe close to. the mainland to have, avoided attention by any power ruling Turkey, and the population, as reflected in a handful of medieval mosques, has -unlike Imvros – historically been about half Turkish Muslim. Covered mostly in vineyards, source of the justly famous Bozcaada wine, the island is small enough to walk around in a not-too-hot day and has some of the best beaches in Turkey.

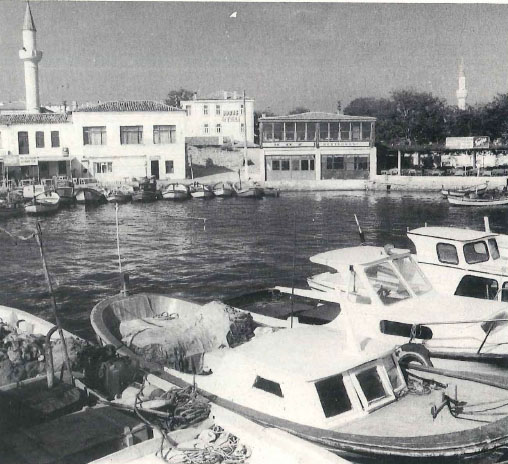

After an hour’s pleasant crossing from Odunluk Iskelesi, with two daily services morning and evening, you will dock at the northeast tip of the island, in the shadow of the castle, whose origins are unkown but which every

occupier – Byzantium, Genoa, Venice, Turkey – has enlarged. The most recent restoration was by the archaeological service in the 1960s. The result is one of the hugest in the Aegean and Turkey, easily equal to nearby Mytilini’s; thank-fully it is not military area, so you can explore every inch – the islanders use the keep to graze sheep, and the lower bayley, inside the moat, as a soccer field.

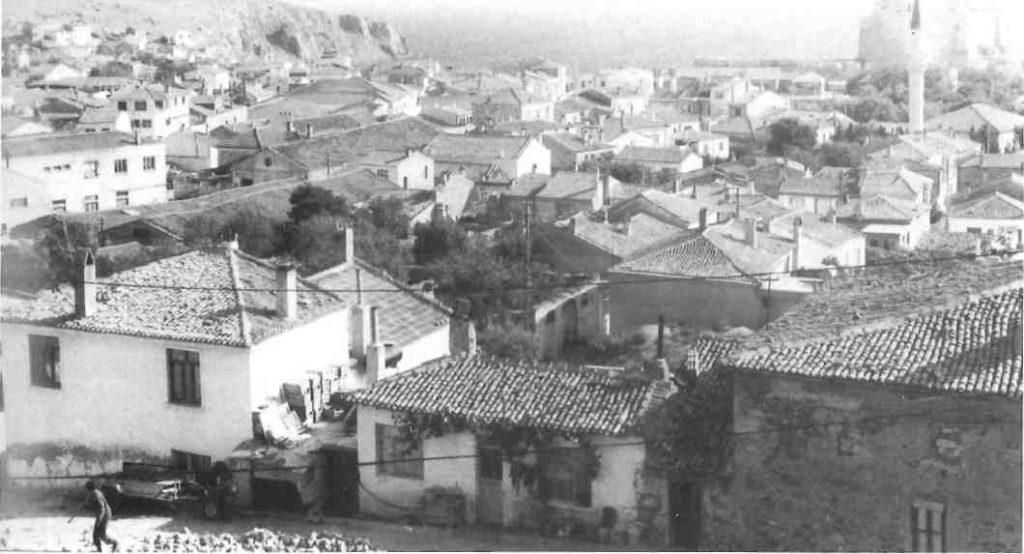

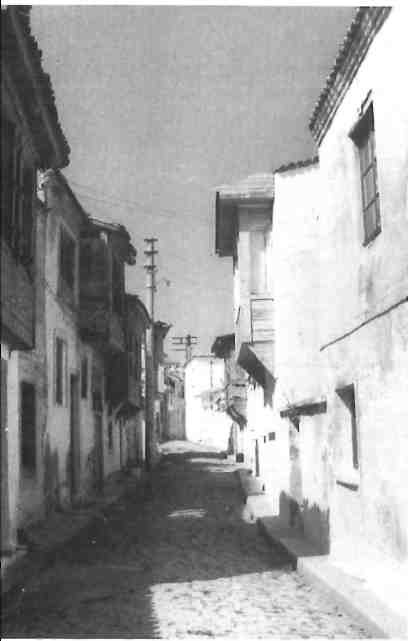

The citadel guards Tenedos single town, which, although built on a dull grid plan along a slight slope, is surprisingly elegant. There is a minimum of concrete, confined to some apartments up on the ridge, and a maximum of old

overhanging second stories and cobbled streets, with a feel much like a Greek island of 20 or 30 years ago. The old Greek quarter extended east from the church, now locked and decaying, to the sea; less than a hundred elderly Greek Orthodox remain following the same sort of government pressure here during the 1960s and 1970s as on Imvros.

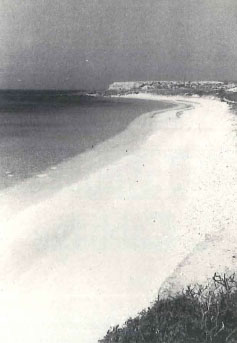

The interior of the island is gently rolling country, even flatter than Imvros and treeless except for small groves marking farms. To get to the three consecutive bays of Ayiazma, Sullubahce and Habbelle, the island’s best south coast beaches, leave town on the main road, taking the right of the first fork and then two lefts. There are few cars, only tractors, and no public buses, since there is not much of anywhere for them to go; a bicycle would be ideal, though hitchhiking is easy.

Just above Ayiazma lies an abandoned monastery with the ayiazma (sacred fountain) in question, dated by an inscription to 26 July 1734. Also on the grounds is an ancient crypt named Dilek Magarasi or Wish Cave, a possible corruption of or pun on direk, Turkish for column, two of which flank the entrance.

A small, seasonal taverna operates behind Ayiazma beach; from next to it a dirt track leads 30 minutes east (left) to Ayiana cove, ideal for determined solitaries. The sea on this side of Bozcaada is incredibly clean and warm for such proximity to the Dardanelles.

There are more beaches on the east shore, reached from the four kilometers of asphalt ending at Tuzburnu, but these are much narrower and more exposed.

A haven this convenient not surprisingly fills up in high summer, mostly with Istanbul natives and Athenian Tenedans visiting relatives who have elected to stay. Then the island becomes “hell”, as one resident bluntly put it, since accommodation is in short supply, as is water – drawn from deep wells and highly brackish.

Accordingly, advance reservations in July and August are essential. The Koz Otel (tel 19651189) has two branches: one on the harbor, plus a giant, converted Greek mansion way inland, both fairly quiet. The Gumus Oteli (tel 19651252), housed in the old school, is atmospheric if spartan at 8 US dollar per person. The only approximation of luxury is the Zafer (tel 19651078) on the bluff opposite the castle; much remoter is the Sezen Motel (tel 1965-1325) out at Tuzburnu.

Obvious place to eat is the small inner fishing harbor, where the Liman Lokantasi vies with the Koz Restaurant (open June to September like its affili-ated hotel). The best food, though, is probably slightly inland at Ayiazma, which commands the finest view of the castle from its roof terrace. Fish is of course a staple, accompanied by the local wine; reliable brands are Doruk; Halikarnass, Talay or Dimitrakopoulou – if fundamentalist teetotalers ever gained total power in Turkey, Tenedos would be ruined.

You will find all the island characters polishing off bottles at Koreli’nin Yeri, a meyhane (kapilio or ouzadhiko in Greek) whose name betrays the fact that its owner did military service in Korea. Here you may meet Mete Amca, ex-communist, self-imposed exile from Istanbul, and uncrowned king of the island’s bohemian contingent.

Vassili, a 74-year-old Greek Orthodox fisherman, once ran Tenedos’ premier taverna until the Cyprus crisis of 1974 forced him to close it. And Mustafa, a Cretan Muslim skipper transplanted here by way of Ayvalik, may invite you to go fishing with him the next morning. You will certainly learn at least as much about Tenedos in the course of a long evening in good company at Kore li’nin Yeri than you will strolling about as a tourist.