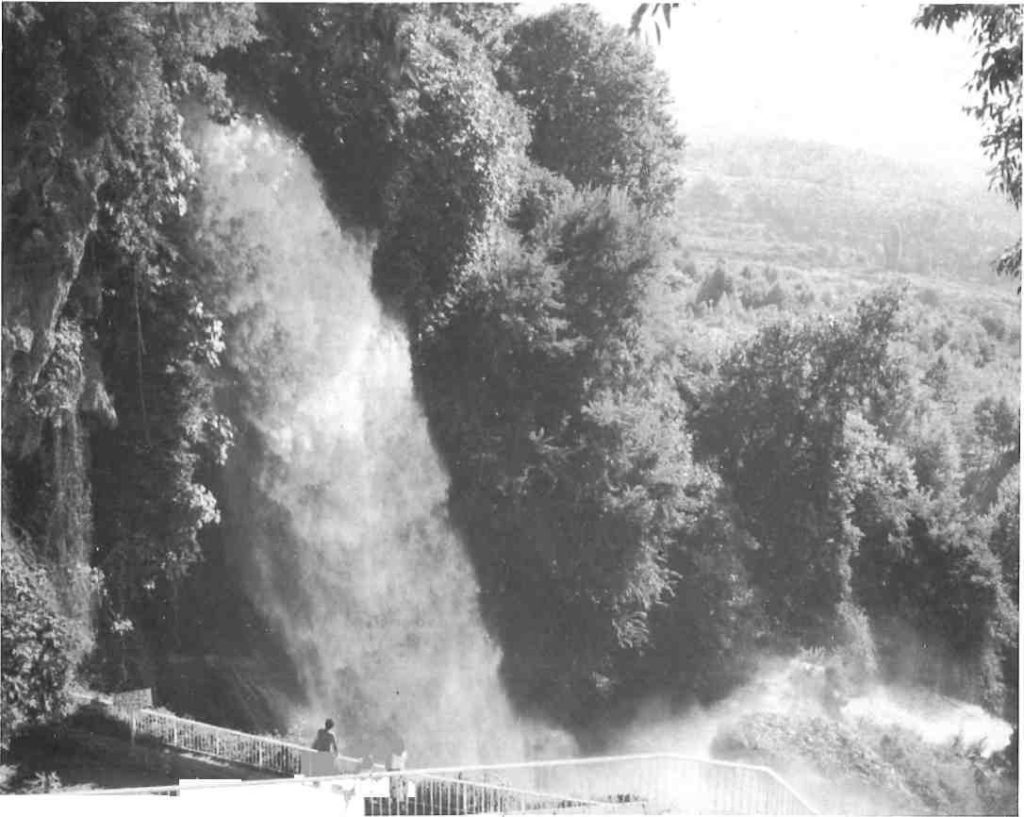

The waterfalls, unique in the country, and the streams that cascade through town are the main attractions for Greeks and foreigners alike, but one of the most likable things about Edessa is that it is not mainly reliant on tourism – and looks it.

The fertility of the soil and the abundance of water make this region agriculturally rich and celebrated for its vast orchards of fruit-bearing trees, such as apples, pears, peaches, cherries and apricots. Vegetables, pulses and tobacco also grow in abundance. Edessa, besides, supports some light industry, chiefly in- textiles, thread, rope, carpets, silk and tanneries. Its main industrial activity, however, is the hydroelectric plant powered by the waterfalls which supplies current to most of Northern Greece. As a transportation centre, it links the provincial towns of Fiorina, Kozani, Veria and Aridaia with the northern metropolis of Thessaloniki.

Strategically located in the passage where the mountain regions of the west descend into the plains extending east Edessa was always one of the important cities of ancient Macedonia, praised by ancient writers and world travellers.

Although the human presence in the area can be traced back to the middle Neolithic period, in Edessa itself, the oldest.findings date from the late Bronze Age. Its size and influence in archaic times, however, have caused some controversy amongst archaeologists. According to some, Edessa was the first capital of the Macedonian nation founded during the reign of Peridikkas, also known as Karanos, King of Imathia, who joined the small states into a federation. According to legend, Karanos, in the ninth century BC, carrying out a commandment given by the Oracle of Delphi, was to found the capital of the new nation at the spot where he came across some sleeping goats (aegis).

At the edge of the bluff near which Edessa stands today, he indeed found goats, which apparently woke up, as he followed them to the site on which he built his capital, calling it, in their honor, Aigai. This is the reason, it is said, why the royal emblem for the Macedonian monarchy was the goat until the age of Archelaos (400 BC) who found it too rustic for his civilized kingdom.

Another legend has it that Karanos found the site of Edessa by following the sound of rushing water and that the name Aigai derives from the ancient Greek word for wave, or water.

Following this line of reasoning, being ancient Aigai, Edessa should also be the place where Philip II was murdered and the site of his royal tomb. On the contrary, Professor Andronikos of the Aristotelian University in Thessaloniki claims to have unearthed Philip’s tomb at Vergina, near Veria, 50 kilometres to the south.

Unfortunately for those who rally round the Edessa-Aigai standard, archaeological findings thus far have not supported their theory, and it appears that, from the Bronze Age down to the fourth century BC, Edessa was merely an agricultural settlement of little note. From then on, it was transformed into an important walled city, probably during the reign of Philip II. The city was divided into two sectors, an upper city built at the edge of the bluff and a lower one at its foot, in an area called Longos now lying deep in luxuriant vegetation.

The 35,000-square-metre (nine acres) upper city was enclosed and protected by cliffs and the cataracts of the river. Although no ancient buildings within its limits have yet been found other than a segment of the city walls, inscriptions describe temples dedicated to Zeus and Dionysos and civic buildings. Outside the city, cemeteries of Macedonian, Roman and Byzantine periods have been unearthed.

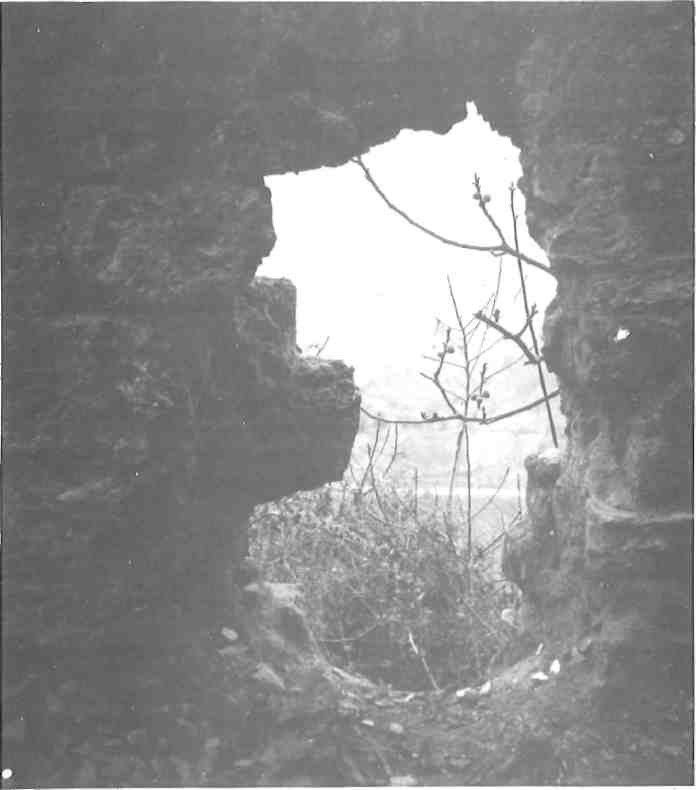

The lower city was extensive, surrounded by walls that were 1200 metres long. The wall and three of the biggest gates were probably built at the end of the fourth century BC, repaired and strengthened over the passage of time. A five-metre high remnant can be seen.

The ruins found at Longos within the walls are, for the most part, early Byzantine private dwellings, workshops and warehouses. The churches date from the sixth century. Yet very shortly after, due to civic unrest, the lower city seems to have been abandoned for the relatively greater safety of the upper city.

During the Byzantine period, the city, then called Vodena after the River Vodas, was an important military centre from 1000-1200 AD which suffered a succession of invasions by Normans, Latins, Serbs and Bulgarians. The last renamed the city Edessa meaning ‘the waters’. In 1389 it fell to Turkish Sultan Vayatzid Gildirm and only became Greek again in 1912.

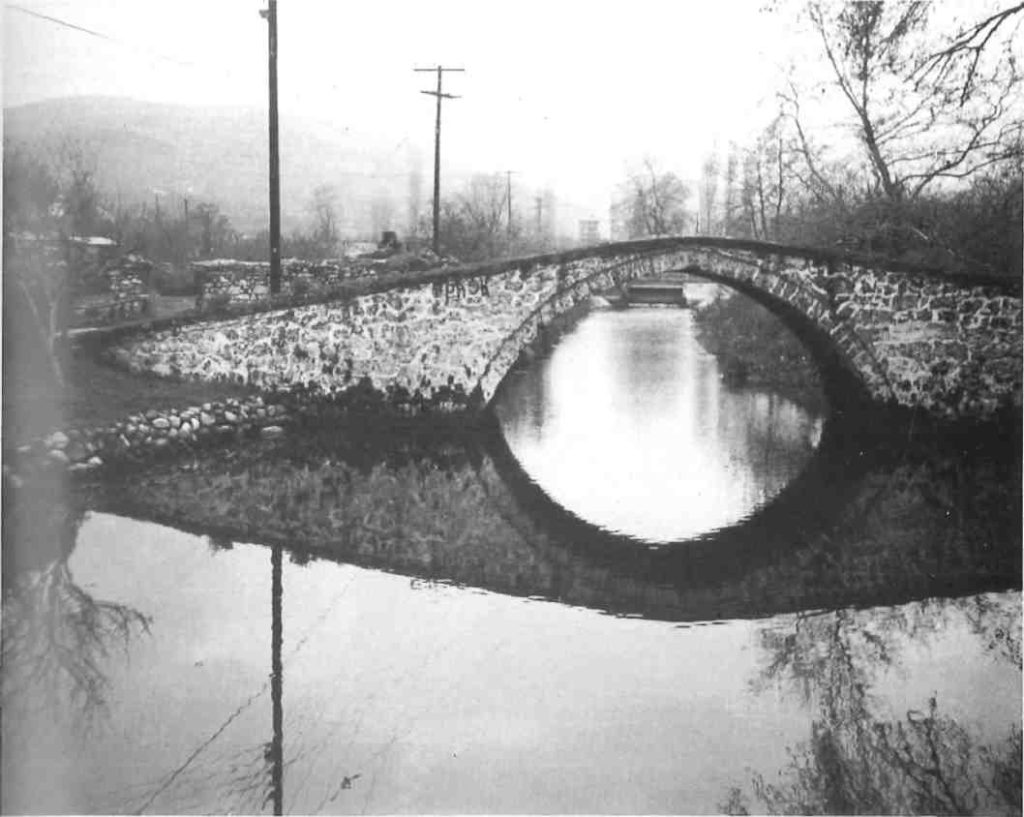

Since then, Edessa has fared well, developing into a rather cozy, prosperous and very livable little city. What first strikes the visitor about Edessa is the abundance of greenery, the small, well-tended parks and the stone walls channelling little off-shoots of the River Edessaios running through the centre of town with picturesque little bridges spanning them at various points. This aspectof Edessa gives it an air of being in some mountain region of Europe, but the overhanging upper storeys, the half-timbered houses, and the numerous well-weathered kafeneia peopled with equally well-weathered, imperious old men proclaim that you are indeed in Macedonia.

The waterfalls which have made Edessa famous are located in the northeastern part of town and easy enough to find as they are well indicated and soon in earshot. They are caused by the River Edessaios, which has its source in the large Lake Ostro-vo, or Vegoritis, as it cascades down some 100 metres from the top of the bluff. To view the panorama of all the falls, it is necessary to descend into Longos near the power plant. Here alone, tourism reigns supreme with its retinue of souvenir and other shops, a feature that mars an otherwise idyllic entrance of magnificent plane trees into the park.

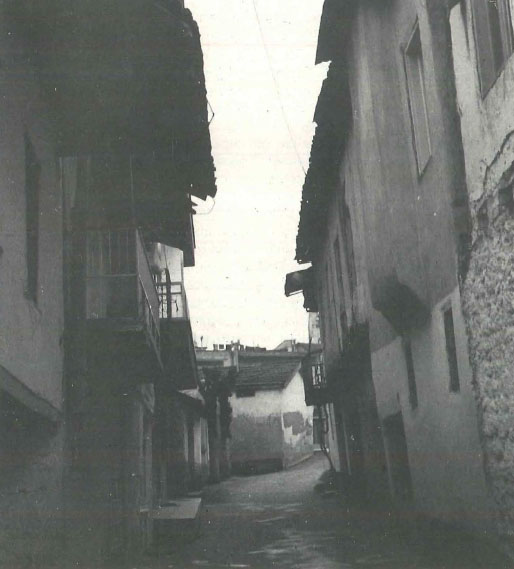

Following the southern most branch of the river uphill you pass through a lovely garden called ‘Angeli Yatsou’ or ‘The Small Waterfalls’. Farther uphill, there is a charming residential area of tiny, single-storey houses flanked by the river on the left and a park on the right. Further up still, lies the small traditional district of Kioupri which has been whittled down to a two-dozen-or-so hovels, few of which are still inhabited. Where Kioupri ends is the Byzantine Bridge over which it is believed that Via Egnatia ran, the ancient road linking Constantinople to Rome. Returning to the centre by the way of Odos Monastiriou you come to the Clock, a tower with six clocks at the top built by Greeks craftmen in the 19th century.

Proceeding towards the cliffs along Odos Archiepiskopos Pandeleimonos, there are several monuments worth look at, such as the Church of Aghia Skepi and segments of the ancient city walls across the street. Unfortunately blocks of flats have been built around this section of the wall, and it is necessary to enter a building and go downstairs in order to see it. At the end of the street there is the metropolitan cathedral, and beside it, the 14th century Church of the Assumption of the Virgin, famous for its outstanding icons and wall paintings.

Formerly Aghia Sofia, it incorporates some ancient columns and some believe it lies on the ruins of the temple dedicated to Zeus. The small church of Peter and Paul can be found in the district of Varosi, an area that has survived better than Kioupri.

Following the road down from Varosi you descend into Longos, the site of the lower part of the ancient city. The trek should be made in suitable footwear since it is steep and takes a good half an hour. The jaunt nevertheless is well worth it, providing a bit of wilderness and a sense of exploration as Byzantine ruins and shallow caves abound in the numerous trails that wind through the lush vegetation. At the foot, there is a breathtaking view back up Psilos Vrahos (the cliffs).

Further along into the valley there are the ruins of the ancient city. The main attraction is a road leading through the southern gate, flanked by seven columns. There is also the site of the Byzantine monastery of Aghia Triada over whose ruins a church was built in 1865. Today it serves as an old age home. Most of the finds excavated in Longos are on display in the Archaeological Museum housed in the stately mosque of Edessa in the south-west sector of the city.

In the surrounding region, a number of interesting events take place annually such as the traditional wine festival in Agras held in June. At the end of August there is a ten-day folk festival in Foustani, near the Yugoslavian border. In early September, at Galatades, there is an Asparagus Festival where visitors may glut themselves on regional dishes devoted to this vegetable when it is at its best. Then in October there is a Green Apple Festival at Arseni.

Although Edessa certainly has its share of interesting sites to offer the visitor both in terms of landscape and historical sites, it is a blessing that local authorities have done relatively little to encourage or promote tourism in the region. The Edessa Information Office located upstairs in the bus terminal has no pamphlets on hand and city hall has no tourist campaigns up its sleeve. This low key approach has allowed the city to remain as serene and refreshing as its delightful location.