Photographs by Ann Elder

On Sunday, 26 May, the foundation stone will be laid for an enduring 50th anniversary memorial, incorporating a museum, chapel . and monument, set on a 42-stremmata ( 42,000 square metres) hilltop site just outside the village of Galatas. It lies above a small and quiet country churchyard.

Looking out on a wide area, where parachutists who had been shot in the air plummeted “like balls of fire” and olive trees “were shredded by gunfire” and Count von Uxkiill landed “without dislodging his monocle,” and from the whole Ayia valley rose “the stink of death”, there are, today, lovely and extensive views along the coast, west to Maleme and east to Chania and beyond to Akrotiri.

Scene of the bloodiest fighting of the Battle of Crete, Galatas has a popular kafeneion run by Yiannis Hadzifarakis, whose father was among the 110 Cretans killed, 40 of them civilians, as well as 145 New Zealanders.

THE MEMORIALS

The kafeneion visitors’ book is a treasury of memories. January 1989: Trooper Bert of the 3rd Hussars recalls being wounded in Galatas and a village woman giving him water and a blanket before he was captured and taken to Athens with many New Zealanders, later escaping to Egypt in a caique.

May 1990: Above an illegible signature, the recollection “Cretans fought with sticks, knives, spades against an enemy with all modern weapons, and after the battle, harbored many Anzacs and British, knowing if they were caught, they’d be shot, with all their relatives.”

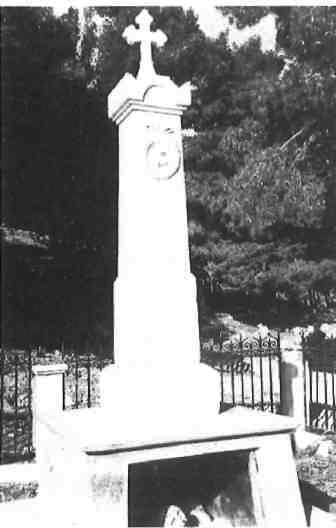

The memorial out in the village square has plaques in Greek and English “to the heroes who fought in the battle for Galatas in May 1941. They sacrificed their lives for freedom. They passed on into immortality and left for us a fine example of courage and endurance.”

In February 1989, Captain Mark Wheeler of the Royal New Zealand Armored Corps wrote: “I’ve learnt here things about myself history books can never teach.”

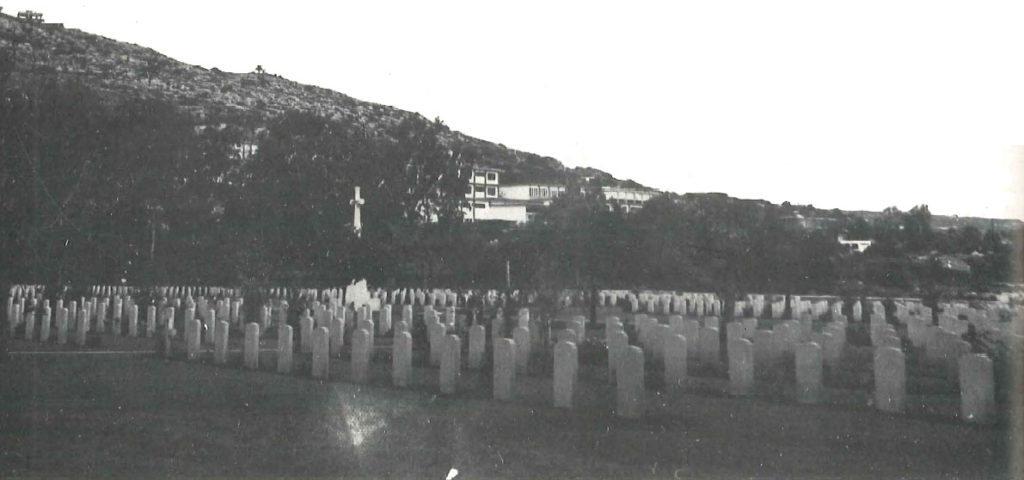

In the Suda Bay Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery, 1545 allied servicemen are buried, 862 British, 618 unknown; 446 New Zealanders, 105 unknown; 197 Australian, 57 unknown; nine South Africans, five Canadians and an Indian.

Cretan dead lie in village graves with memorials at various places: Kastelli, Ayia, Kandanos, Alikianos, Kolimbari, Suda, Maleme, Chora Sfakion.

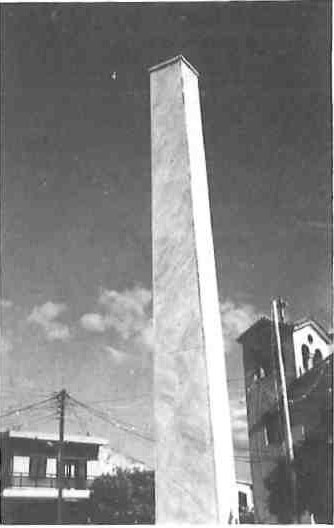

That of Maleme is simple and laconic: a gaunt marble plinth with an etched olive wreath, and the epitaph “To you who gave your life for the fatherland.”

airborne battle was won in the annals of World War 11.

Sfakians are more blunt: the monument, on a pine-covered hillside above the beach, has skulls and bones displayed in a glass case under a column covered with names, quite often several from the same family, and below the words “Patriots executed by barbaric Germans (patriotai ekteiesthentes ipo barbaron Germanon),”

The Suda Bay visitors’ book comments reveal that the English are impressed with the standard of care lavished on the beautiful seaside spot by chief gardener Nikos Tsoulos and his assistant Pantelis Gavrelakis. Last month, the two were still busy planting herbaceous borders and new shrubs.

“Everything must be perfect for the 50th Anniversary” said Tsoulos.

Ten kilometres west of Chania, on the coast above Maleme, where the Battle of Crete was decided, tucked under the historic Hill 107, of the total 6580 German dead, wounded or missing, 4465 are buried, the cream of the Nazi air force. There are many unbekannter Deutscher soldats, unknown German soldiers. Most were 20 or 21 years of age.

“They picked the really young,” says a German tourist on holiday, “because their bones are strongest and are best able to withstand the shock of a parachute landing.”

Amongst those buried here is General Bruno Brauer, the Commander in Crete. He was executed on 20 May, 1947, after having been found guilty of war crimes at a trial in Athens.

Ironically, he was lowered into his grave by George Psychoundakis, the veteran andartis whose memoir, The Cretan Runner, is the most famous account of the resistance. He fell on hard times after the war and applied for the post of caretaker in the German cemetery – motivated, some say, by a streak of black humour.

“Many assembled to meet the body,” Psychoudakis says. “They would have torn it apart me fa heria if the police had not intervened.”

With another distinguished Cretan guerrilla, Manolis Paterakis (who fell to his death in the mountains while seeking a lost goat in 1985), Psychoundakis has maintained the Maleme cemetery from its opening in 1974 until his retirement five years ago. “It was work,” he says.

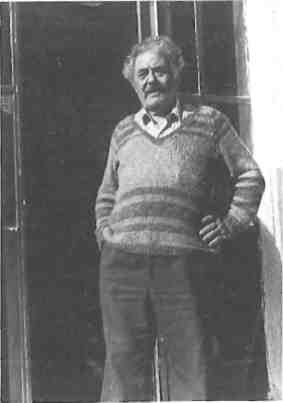

Markos Polioudakis of Rethymnon,

author of “The Battle of Crete”, 1983.

Yiannis Hadzifarakas, in front of his

kafeneion, Galatas.

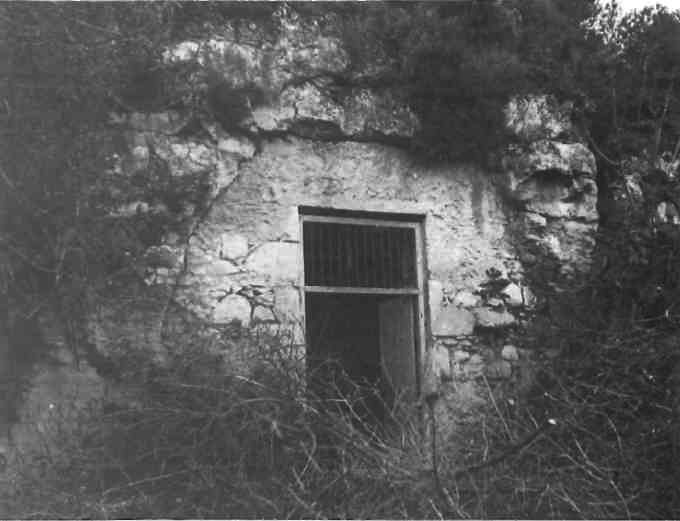

Greek monument at Sfakia, with skulls

of the executed in the glass case

below.

Tomb of the legendary New Zealander,

Sergeant Dudley Perkins, ‘The Lion of

Crete’, Suda Bay Cemetery.

Greek-New Zealand memorial,

Galatas.

Explaining the resistance, he wrote: “What did they expect us to do? Cross our hands and surrender? This our souls forbade us to do. Our history too… had taught us a different lesson.”

A scholarly man, he has translated the Odyssey into modern Cretan, a language purer, he believes, than mainland Greek. The translation has been adopted for use in Greek schools, and he is now working on the Iliad.

The sorrowful sight of so many soldiers’ graves leads Greeks to thoughts of peace.

“No more war, only peace,” reads a recent Greek entry. “Peace, freedom, love. I will never forget,” reads another.

“No words can describe our feelings, seeing all these graves. Without your help we would not be able to live in peace. Thank you,” wrote a Greek on 16 November, 1990; and on 21 November, another Greek added “No war in the Persian Gulf.” And yet another, “Peace”,

THE WITNESSES

Andreas Vandoulakis

“Old friends like Patrick Leigh Fermor and Xan Fielding as usual will be here, we hope, for a gathering we will put on. Nothing grand, as our financial situation is not the best,” says Andreas Vandoulakis, president of the Chania branch of the Cretan National Resistance Association.

“Our resources are mostly used as needed, putting up memorials and maintaining them in villages around’ Chania where Cretans died in the war.”

Vandoulakis was unable to reach Crete for the battle, having been trapped on the mainland with a regiment which fought in Albania. He returned in June after Crete had fallen. “Our house in Vafes was full of British, Australian and New Zealander soldiers who had not escaped,” he recalls. His own family of eight brothers and two sisters, and a large related family, were renowned for hospitality to andartes and support for resistance activity in their Sfakiot village four kilometres from Vrisses.

Andreas Vandoulakis, President, Chania Branch, Cretan National Resistance Association.

Markos Anitsakis outside his taverna in Chania.

We worked with the British, helping gather intelligence and carrying out sabotage operations, like blowing up. German warehouses. After the war, I was caretaker with Atlas and other companies until retiring with a heart complaint,” he says.

In a manner of utmost gentleness and modesty, now white-haired and a little frail, Vandoulakis divides his time between home with Maria, his wife, also from Vafes, the company of his son and daughter, and Andreas, his grandson, and the neighborhood kafeneion.

Stratos Papadakis

“I have never forgotten the troops passing in vehicles on the way to Chora Sfakion, throwing chocolates and sweets to us on the side of the road.

Then we watched again, as those troops who had not been evacuated came back, as prisoners-of-war, on foot, hungry, thirsty and tired. They begged for water, but armed guards pushed them back and hurried them on if they tried to step out of line,” says Stratos Papadakis, prefect in Irakleion, who was in charge of organizing the regional anniversary program from a nomarchy office overlooking Liberty Square.

“I was 10 at the time. We lived in Chania. My father was an exporter of olive oil and leather goods. We fled at the end of May, as the town was burning and about 40 warships were ablaze in Suda Bay from Stuka bombing. We went to Vrisses first, then on to Imbros, where the road ended. After about a month we returned to Chania for the rest of the war.”

Maleme Memorial.

Freyberg HQ at Akrotiri.

Markos Anitsakis

“Chrysavgi was betrayed by its mayor for having killed a German soldier and buried the body secretly in a vineyard,” says Markos Anitsakis, proprietor and chef of I Vouli (The Parliament) taverna in central Chania, also treasurer of the Chania branch of the Cretan National Resistance Association. “The mayor presented himself to German authorities and told them what had been done. He was executed on the spot.”

Anitsakis remembers the Battle of Crete as an 11-year-old in the taverna his father and uncle, after years in Alexandria, had opened in Hadzimihali Yiannari street, named for the hero of some other Cretan resistance against an earlier foreign occupation.

“Cretans value freedom because they have known-slavery,” he says. To illustrate his point, he dips back 300 years into ancestral memory. “Those dapia were built with decades of Cretan slave labor,” he says, pointing to the huge bastion in the old city walls beyond the block opposite.

“Forebears of mine worked for 50 years – a lifetime, yes – building those for the Turks. Two brothers were put to work on different sections. Conditions were so harsh, they did not meet again till the walls were finished. Each asked the other where he came from: Suda. Your name? Your father’s name?”

“That is sklavia, slavery. We are free now. We live in the birthplace of democracy. But we do not have good politicians. I read in the paper the other day of a British member of Parliament stopped for drunken driving. He was fined 250 British pounds and lost his license for 15 days. That could never happen here to a vouleftis, an MP.”

“There has only been Venizelos. If he had been president of a big country, the history of Europe this century would have been different.”

Vassilis Konios

fettle at 80.

“They were the best years of my life. You said Yeia sou. Kali tyche to someone going on a mission, knowing he might never come back. When one died, it was as if my daughter here had died.”

An old andartis in fine fettle at 80, and veteran of the Albanian campaign, Konios is from the village of Favriana, just inland from the small southern port of Tsoutsouros.

As an area evacuation organizer, he disclaims great deeds, saying his abiding memory is of standing up to his chest in the sea at night, helping troops in and out of small boats, ferrying them to British warships and submarines, and handing ashore British agents like Tom Dunbabin, Sandy Rendel and Paddy Leigh Fermor.

So successful were the Tsoutsouros evacuations that surrounding villages suffered severe reprisals.

“In 14 villages, 400 were killed. They were not armed soldiers, but women and children.”

As a key figure, he became well-known to the enemy and hunted. Sought at home, as he hid behind the door, his coolheaded mother disowned him before the intruders, saying he was no son of hers, but her husband’s by an earlier marriage.

“My hardest moments in the war were deciding whether or not to escape to the Middle East to avert further reprisals. I knew I’d be useless in Egypt, so I stayed.”

His anecdotes range from the inception of the resistance by 12 men meeting in a cave at Ayia Sila to tense days hiding among petrol barrels while waiting to help British commandoes sabotage Irakleion airport. He tells of hair-breadth escapes, six men and a mule concealed only by bushes, from pursuing Germans – and of nor killing Germans to minimize reprisals.

Konios tells these stories with Homeric exultation. The symfilia (camaraderie) that grew up among Cre-tan and Allied andartes in mountain hideouts made for experience never to be paralleled in peacetime. English agents spoke Greek, based at the beginning on some knowledge of ancient Greek. They relayed on the news from secret radio stations to Cretans and produced a small newspaper in Greek “to give courage to the people. We are not an organized or orderly lot and the war seemed like something we couldn’t cope with.”

For Konios the civil war that followed was far worse than the occupation, without a trace of distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’, nor camaraderie. He became a communist. As for his politics today:

“I’m on the side of the good man, judged by his acts, nothing else. Deeds matter more than professions of faith or political ideals. Christ on the cross died a communist’s death.”

Being unlettered, Konios has taken up with delight a tape recorder to relate his wartime story. With 14 full cassettes, he is still at the beginning. If 50 years have not dimmed his memory or fiery-spirited zest for life, they have dulled his hopes.

“I didn’t fight for glory or money, only for my patrida and a peaceful world. I grieve this has not come about.”

Emmanuel Stagakis

musical instruments and makes

furniture today.

“We were thirsty and hungry and fighting ‘chest-to-chest’. It’s a miracle we survived. I don’t know how we held out.”

In his woodcraft workshop off the main road by the sea just west of Rethymnon, Stagakis remembers what it was like in the thick of one of the most successful operations – preventing the seizure of the airstrip nine kilometres east of the town.

A survivor of the Albanian campaign, he needed treatment for frost-bite in a hospital in Athens. Mustered back into service and sent home, Sergeant Stagakis found himself facing the airborne attack starting on 20 May.

“The ghastly image of those days will always stay in my memory,” he wrote in a 20-page memoir published 18 years ago and reprinted two years ago. He cannot bear to go far in giving the account again.

When the battle had to be abandoned, Stagakis took to the hills as an andartis, though he would return home to repair damaged buildings. “I had to. No one else could do it.”

From dealing in wood, he took to working it as an artisan in post-war years. His flow of creations ranges from fine dining suites, desks and armchairs – many with Minoan motifs like horned bulls, partridges and the Prince of the Lilies – to constructing musical instruments like the lyra and bouzouki.

As a full-blooded regular front liner, Stagakis feels neglected as the special anniversary is being planned.

“Every year I complain that they don’t let us know what’s going on.”

Maria Manolaraki

Auschwitz.

“We struggled hand-to-hand and took their weapons: they would have killed us if we hadn’t. We hit them on their heads with their own weapons. We killed six.”

As a girl of 17, she and her younger brother, Vassilis, were confronted by German paratroopers falling onto their village, Chrysavgi, southwest of Maleme.

“There was the smell of dearth for days,” she recalls today in her flat in the centre of Chania near the bus station. “The battle was a catastrophe. It .ruined Crete like an earthquake.”

After half a century the number 82211 branded on her left forearm is faded and blotched, but memories of the three years she later spend at Auschwitz well up in all their horror.

“They treated us like dogs. God knows how we survived, but I was never ashamed. I held my head high.”

Manolaraki was one of 19 Cretans deported to Auschwitz. The one other woman, Chryssoula, from Irakleion, now lives in England. Fleeing occupying German forces after the battle, Manolaraki joined up with the Petrakis band of 800 andartes in the White Mountains. On the East of the Assumption, 1941, she was captured.

For a while Manolaraki was in Ayia Prison, a complex of buildings south-west of Chania, which played a crucial role on the first day of the battle. She found her compound full of women, from grandmothers to young girls.

“Every morning at five they executed some of us, sometimes as many as 30 in reprisal for Germans killed somewhere.”

Thanks to an amnesty, she avoided death, only to be sent away as a prisoner-of-war, first to jails in Serbia, then to Auschwitz. There Manolaraki and Chryssoula were put to work in an arms factory.

“We worked in silence. Talking was forbidden. Then one day there was a lot of shouting. We understood the war was over and took to our heels. We had no idea where we were. Once we nearly took a train from Siberia. After many trials we found our way back home.”

The young man she had been engaged to was still waiting for her, but her brother had died of hardship during the occupation. A widow for seven years now, she has two daughters and four grandchildren.

In Chania, Manolaraki is respected as a woman of tremendous strength, as an example of the greatness of the Cretan spirit. Her story, though, has still to be written.

Leafing through folders of cuttings and pages of handwritten notes, she picks up a photo of herself at 17, a slim girl laughing over her shoulder as she reaches up to pick fruit.

“See what I was like when that catastrophe struck, in little socks and little shoes…?”

Stavros Kapridakis

Viannis, with his sheep.

“How can a village like this afford tractors and automated potato planting? But look at those fat-cheeked politicians: What do they care?” Guerrilla veteran Kapridakis today has little faith in contemporary political management and a marked disdain for those in power. He comes from Askyfou, one of those amazingly flat mountain plateaus which dot the Cretan mountains from Omalos in the White Mountains and the Plain of Nidi on Psiloritis (Ida) to Lassithi of the 1000 windmills.

For the defeated Commonwealth troops retreating to the south, Askyfou was like a moment’s stop at paradise. For those who were denied passage to Egypt, it was another station of the cross on a two-way Via Dolorosa, up to Golgotha and back.

As a teenager, Kapridakis spent the resistance with a small band of shepherds living in caves armed with weapons procured by the retreating Allies.

From June 1941 until early in 1942, when evacuation was arranged, his family sheltered a New Zealander in his mid-20s, a medical orderly. Each day the stranger was sent up the mountain-sides to avoid detections, then returned at night to eat and sleep.

Over the years his name has been forgotten and the letter he wrote after the war mislaid, though the family re-members he took up farming with cattle and wheat-growing, which suggests Canterbury. They wonder, is he still alive? What has happened to him?

Gunfire and violence hit Akifou only on 13 September, 1944, on a foggy, rainy day, when, in a brief fracas, Kapridakis shot dead a German captain and was wounded in his hip, leaving him with a limp.

With the responsibilities of village president for 25 years, he has learnt to take a broad view, helped perhaps by Askifou’s remoteness, its *being untouched by tourism, its self-sufficiency (except in olive oil), maybe by the clarity of its air, dazzling with stars at night.

Today the ferocious internecine strife in post-war Iraq takes him back to that which tore Greece apart form 1945-1949. Events seem to him to be following just the same pattern, with the party in power using all its resources to crush the left-wing opposition, offering the strongest resistance.

He keeps up with the development of the single market after next year. “The EC market will only bring slavery back to Greece again,” he says, eating rice and sipping cold water with the monk-like simplicity of the shepherd he is, getting up at 5 am to take out 100 sheep.

The visiting village priest and foreign guest eat delicious savoury fresh lamb in fragrant tomato sauce”with fine old cheese made by Stavroula Kapridaki, and drink wine from the little vineyard.

Coming in at nightfall from overseeing the milking, he looked up round the bare slopes. “It is the most beautiful place in the world. Fifty years ago it was paradise. Oaks covered the mountains . thickly, their branches intertwined. We had our own places for firewood. We took a tree here and there and allowed natural regeneration. The woods were the habitat of many partridges. Now fires and wholesale felling have caused all this erosion.”

THE CHRONICLERS

As these Cretans fought for their island with fire in their bellies 50 years ago, others are now writing accounts of the battle. Among notable achievements is that of Markos Polioudakis of Rethymnon, who published there his Battle of Crete in 1983.

It contains much German material, and maps and photographs checked by Australian authorities. The motivation for his 10 years of work may<be found on page 516: five members of the Polioudakis family are recorded as having been killed by Germans.

“As a boy of 10, Markos saw his father shot in front of him,” said a friend.

A recent addition to resistance chronicles is from andartis Giorgos Faragoulitakis, code-named ‘Skoutelogiogos’. His account, The Crosseagles of Psiloritis, was published in Irakleion in March. The tome is among stacks of resistance material at the fingertips of Rethymnon doctor Nikolaos Kokonas, son of the Yerakari teacher, Alexander, among the most respected figures of the resistance.

Babis Pramatevtakis, composer of “Ode to ttie Battle of Crete”.

George Psychoudakis, frontispiece from his memoir, “The Cretan Runner”.

Maria Sakaraki, f.ilm director, whose documentary will be shown on Greek and Australian TV this month.

Kokonas has compiled an anthology of British espionage in Crete, published in mid-April. It is based on a dozen accounts written for him by leading .British agents working on the island between 1941-1945. He also has in hand the final report of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) by Jack Smith-Hughes, classified material in Britain, he believes, but parts possibly usable in a forthcoming publication he has in mind.

For younger Cretans the battle has taken on a legendary character and has become another of the seminally-in-spiring occurrences studding their island history. For Rethymnon composer Babis Pramatevtakis, the battle stands beside the blowing up of Arkadi Monastery in 1866 as a source of creative inspiration.

“To compose for it was always in my mind,” he says. On his return to Greece in 1978 after 10 years’ study in Munich, Pramatevtakis began composing a musical fantasy, “Ode to the Battle of Crete”, to the lyrical verses of Dimitris Aetoudakis, also from Rethymnon.

First performed in Athens in 1975 with the famous Cretan actor Manos Katrakis narrating, then released as a record the following year, the work has wide appeal as a commemoration of a battle for freedom, that could have been fought anywhere.

Classical in form, but with Cretan instruments like the lyra in the orchestration, the stirring and haunting work was to be recorded again in Athens after Easter with the 80-member DEH choir and the 20-piece Rethymnon civic orchestra, with vocal soloist Vangelis Stefanakis.

Excerpts may be heard in a film directed by Maria Saharaki, produced by Eva Ladia, scenario by George Koukas, to be screened on Greek and Australian television to mark the 50th anniversary.

“The film will be basically historical, with clips from German archives and scenes based on Markos Polioudakis’ book,” says Saharaki. “Cretan dances and music will also be used,”

THE GUESTS

German Chancellor Helmut Kohl has accepted an invitation to join the Duke of Kent and Prime Ministers Constantine Mitsotakis, Bob Hawke of Australia and Jim Bolger of New Zealand, in a celebration of peace and friendship in Chania on 26 May.

Symbolic flame-lighting, releasing of doves, scattering of flowers and singing of national anthems to military band accompaniment are planned, as several parachutists make descents into the stadium venue in commemoration of the Luftwaffe invasion.

The night before Mr Mitsotakis is expected to entertain leading visiting dignitaries in his family home at Akrotiri on the outskirts of Chania while other visitors attend a reception planned by the Greek armed forces in Chania. Earlier in the evening Mikis Theodorakis, also Cretan, is to conduct the Greek Radio Orchestra in a performance of his Pnevmatiko Emvatirio (Spiritual Pilgrimage) to the verses of Anghelos Sikelianos.

Among philhellenes, scholars and diplomats with Cretan connections expected for the occasion are Earl Jellicoe, Professor Nicholas Hammond, the Honorable CM. Woodhouse, Patrick Leigh Fermor and Xan Fielding. The Chania branch of the Cretan National Resistance Association looks forward to hosting a gathering of old andartes.

Events in Athens will include memorial services at the Phaleron war cemetery and before the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Syntagma, where, around the sculpted figure of a dying warrior, the passerby may read parts of Pericles’ funeral oration, as recorded by Thucydides:

“They gave their bodies to the commonwealth and received… praise that will never die, and with it the grandest of all sepulchres, not that in which their mortal bones are laid, but a home in the minds of men, where their glory remains fresh to stir to speech or action as the occasion comes. For the whole earth is the sepulchre of famous men; and their story is not graven only in stone over their native earth, but lives on far away, without visible symbol, woven into the stuff of other men’s lives.”

Lord Freyberg

A significant contribution to the 50th anniversary will be a new biography in English of the Allied Forces’ commanding officer, General Bernard Freyberg, written by his son, Paul.

The battle was fought against worse odds than necessary, because Churchill vetoed last-minute troop redeployment which would have led Germany to suspect its most secret radio code had been broken, he says.

“My father,” Colonel Lord Paul Freyberg explained to me in a recent interview, “was in the agonizing position of being unable to position troops for a solely airborne invasion, for fear of revealing the code had been cracked. There’s no point in trying to keep it quiet any longer: so many know of it.”

The chief of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force was chosen on Churchill’s recommendation to lead the British and Anzac troops in the defense of Crete shortly after the German code had been deciphered at Bletchley Park in England, thanks to the Enigma machine, producing what was called ‘Ultra’ intelligence.

Much though Churchill wished to hold Crete for strategic and political reasons, his top priority was to keep from the Nazis that their code had been cracked. “So the battle was fought, less to keep Crete than to ensure the Germans would not realize their code was broken,” said the biographer Freyberg.

“My father was in the Prime Minister’s dog box for a year or so afterwards. Churchill thought he should have been able to hold Crete. But when he was wounded in the western desert, there was a cheery note from 10 Downing Street.”

“But repercussions of the Battle of Crete were with my father for the rest of his life. He very nearly got the sack for losing the battle. There were commissions of inquiry and so on. But Peter Fraser, the New Zealand Prime Minister, stuck up for him.”

“The contention against him was that he should have let the New Zealand government know how hopelessly unprepared Crete was. But he considered it was not for him to bellyache, and to give an opinion only if asked.”

In his view the Greek campaign of 1940-41 should never have been attempted: “It hadn’t a hope. It was a political decision made because the Greeks had been a gallant ally, but was a shambles from the beginning, the bottom of a particular trough, a very traumatic time.”

Colonel Paul Freyberg is among the youngest living British veterans of the campaign, having left Eton at 16 to fight with a battalion in action around Mount Olympus, and then Thermopylae. Evacuated to Egypt, he fought with the Long Range Desert Group until he was old enough to join the Grenadier Guards.

He undertook the biography in accordance with one of his father’s last wishes, on the belief no one outside the family understood his double life, half in England, half in New Zealand. He may seem to glorify his father,however. Even a disinterested historian like I. McD. G. Stewart compares the General to Harold of Hastings and Prince Rupert who fought against the Roundheads, saying he showed the same “impetuous daring, later to be tempered with sagacity.” Churchill himself referred to Freyberg as ‘the Salamander’.

Author Dr Charles Cruickshank recently described the fall of Crete as “a formidable catalogue of failure,” concluding that “the scene was set for as hopeless, unnecessary and gallant a defensive operation as British troops were ever condemned to undertake.” The new biography, due out from Hodder and Stoughton in time for the anniversary, should help explain why.