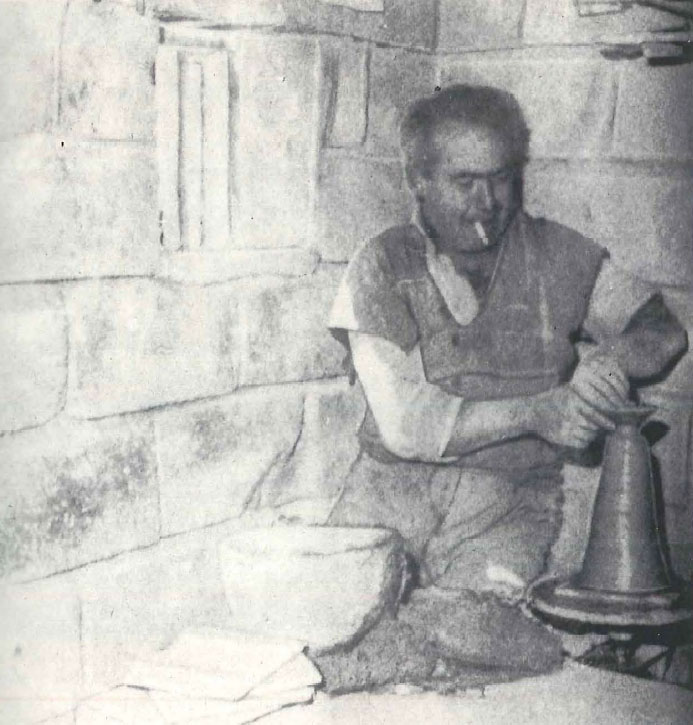

On a sunlit hillside outside the Rhodian village of Archanghelos, Panayiotis Patouras has his workshop. The 67-year-old artisan may easily be the last true folk potter in the country. Alone in a cement-block shack that has no electricity or running water, he turns out each year some 4500 handmade pieces that connect him to a tradition dating back to the neolithic period. When he dies, that noble tradition will disappear with him.

Rhodes, as recently as the beginning of this century, could boast of hundreds of folk potters like Patouras. Thanks to an ample supply of red or buff clay, the island began to develop a ceramic industry as far back as 590 BC when Cleoboulos, one of the Seven Sages of ancient Greece, returned to Rhodes from a trip to Egypt bringing notations on the art of pottery with him. The islanders began to show considerable skill at the craft and developed a characteristic style of work.

As Arthur Lane has noted in his historical survey Greek Pottery, “…the Rhodians’ favorite material was… a coarse clay coated with a fine white slip as a ground for painting. Shapes tended to clumsiness in comparison with those of the mainland where a finer clay, needing no slip, was normally used; and the designs were painted broadly with the brush alone, while on the mainland finer brushwork was gradually superceded by the black figure silhouette with incised details.”

It was only in the 15th and 16th centuries, when Rhodes was under Ottoman rule, that Rhodian terracotta became well known, owing to its use of vivid colors and decorative motifs. Its geographical position, convenient to Cyprus and Crete as well as to the mainland of Asia Minor, was another factor that enabled it to become an important centre of pottery.

Rhodian potters not only sent their wares abroad but often accompanied the goods themselves, peddling them by donkey and camel in Turkey, Lebanon and Syria. Patouras himself can remember how, as a 12-year-old, he went on three and four-month-long selling trips with his father.

“It was an exciting and wondrous time for a boy, though often very difficult and treacherous,” he recalls. ‘One time the donkeys were attacked by flies. They were so maddened, they ran to rub themselves against trees, smashing all the pots they were carrying.”

Patouras, a small, stocky but vibrantly alive man who loves a good joke and his glass of ouzo, smiled broadly when describing what it was like to ride a camel: “There is nothing quite like the feeling of rising into the air when a camel picks himself up from a kneeling position.”

The 1920s saw the end of that colorful period when Rhodian folk potters could no longer roam at will selling their wares and observing the work of other ceramic artisans.

“Rhodes and the rest of the Dodecanese islands were taken away from Turkey and given to the Italians after World War I, and they wouldn’t let us leave the island,” Patouras explains. “All we could do was sell our goods to other villages and the occasional tourist.”

In 1929, the Italians founded, together with local partners, the first mass-produced ceramic factory on Rhodes, the Ikaros Company. The plates and pots produced here were slip cast. Liquid clay was poured into a plaster-of-Paris mold. After it was fired and transfers applied, children did the decorating, in- effect putting on the color by numbers. It was quick and cost-efficient work, but every piece was done in the same uniform way, stamped out like a cookie.

Mass-produced or not, Ikaros’ products were commercially successful. As SA Papadopoulos has noted in Greek Handicrafts “The products of this factory created a neo-Rhodian style that standardized many of the older folk designs. These Ikaros pieces, which are good faience, have flowers, branches and other decorative motifs painted in bright colors – red, blue, green, purple and black, usually on a white ground.” “Other typical motifs for decoration plates are the young deer, composition of a medieval 3-masted ship in full sail on a sea enlivened by fish, and the outspreading composition of dense foliage repeated in kaleidoscopic geometric patterns, everything vivid and brilliantly colored under the strong glaze, which gives depth to the decoration.”

Papadopoulos also noted that the Ikaros factory not only became the most important producer of Rhodian pottery, but also the school which has produced most of the potters presently working on the island.

There is ample work for these potters, as Rhodes in the past 25 years has become one of the major tourist centres in the Mediterranean. With over 200 high-rise hotels in Rhodes town alone, a modern airport which receives as many as 80 charter flights a week from northern Europe, and just about every cruise ship plying the Aegean dropping anchor here, selling mass-produced ceramics to the 1.5 million yearly visitors to the island has become a booming and lucrative industry.

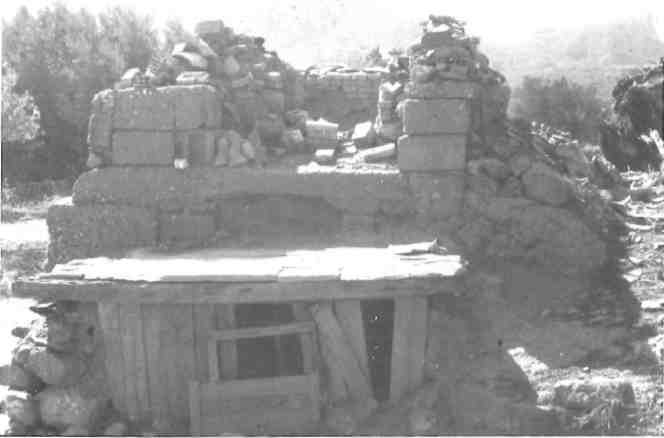

Patouras is the only potter left on Rhodes – indeed in all of Greece, he insists – who still works in the classic, old-fashioned way, digging and preparing the clay himself, spinning it on a wheel not unlike the wheels used by his ancestors, firing his pots in a simple, wood-burning, updraft kiln that Cleoboulos himself might have designed. Most of his work is designed to be used, not hung on a wall.

It is not by choice that Patouras must work alone. None of his five children has opted to follow in his footsteps, as he did in his father’s and so on, going back six generations before that. “They find the work too hard and the pay poor,” he explains with more than a tinge of bitterness.

The master ceramicist did have one helper in recent years, Lynne Fischer, a South African-born potter who came to Rhodes and sought Patouras out when she heard he was still hand-making his pieces.

“I became his apprentice and worked with him for three years,” Fischer says. “Panayiotis is a great potter and I learned so much from him, but the time came when I had to go off and strike out on my own.”

Fischer now lives in Lardos, another village on Rhodes, utilizing her own wheel and electric kiln to do custom jobs for hotels, restaurants and individuals. She also teaches pottery to a select group of Greek and foreign students.

Patouras’ reputation has also drawn the attention of two outstanding Scottish potters, Don and Irma Ewen, who have made it a point to visit his workshop just about every summer for the past ten years.

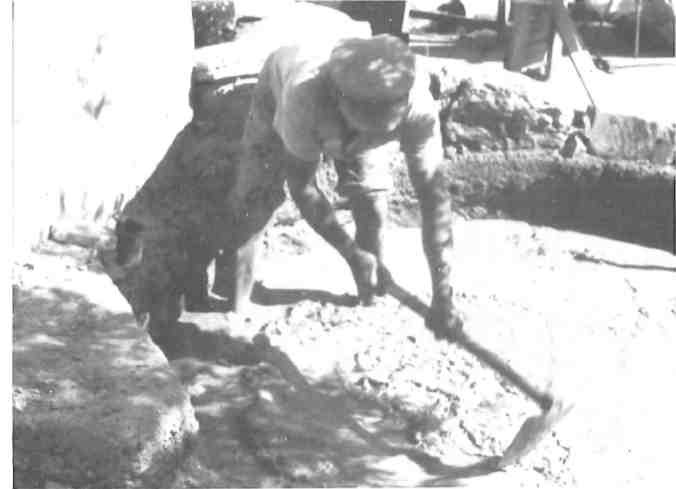

“To watch Panayiotis in action is something miraculous,” Don Ewen says. “It’s like watching a potter from the Stone Age come alive before your very eyes. He digs the clay out of his own hillside, then washes and sieves it himself, filtering it with clumps of thyme, feeding it into various pits. Then he finally rolls it up, like turf, and stacks it for the wedging. Later he cuts the clay with a piece of fishing line and wedges it again.”

“When he sits at the wheel in his shed and starts throwing pots, I think of him as God in the act of creation,” Don continues. “Outside of the Orient and maybe eastern Europe, nobody today is doing what Panayiotis can do. He does a lot of extended throwing, for example, doing sections in steps. He’ll add on pieces later, after setting a pot aside. Other times he’ll put handles on when wet.”

“He also does a lot of the big amphorae called kioupia on Rhodes.