There is no doubt in the mind of Deputy Vice President and Minister of Culture, Tzannis Tzannetakis. “This project is a necessity that must be fulfilled now. It is a museum for the world.”

“On the other hand, it is no ordinary museum,” he continues. “It is totally specialized, displaying all the treasures of the Acropolis which we have been obliged to remove from the monuments due to damage from pollution.”

It will include, of course, the contents of the present museum up on the Rock, works of art scattered in other museums and those in storage. For the visitor, it will present the Acropolis experience as a whole.

Yet, fears are expressed by authorities and independent experts, as the contract was being signed with the winning architectural team, that there are still problems of substance that need to be solved.

Today, in this month of March 1991, everything seems to indicate that the most controversial and complex issues concerning the erection of this museum seem to reach a solution. Mr Lucio Passarelli, the civil engineer of the Italian team which was awarded the first prize in the competition, was last month on his third trip to Athens, to sign the contract concerning the design and discuss the legal aspect and other details of the project. But already the first objections have been heard, not only from the Greek Association Architects, which refused to participated in the jury due to disagreement in regards the construction sites and theterms of the competition, but also from many specialists and laymen, as well as from two members of the jury who had judged the contest.

The whole concept of a museum dedicated solely to the Acropolis is a revealing one. The first museum, situated on the northeastern side of the Parthenon, was completed in 1874. Built in such a way as to be integrated with the rock and not obtrude on the monuments, it was intended to house the archaeological wealth found on the Hill. However, despite the extensions and large-scale additions built before and mainly after World War II, its exhibition area proved inadequate because of the ever increasing number of findings belonging to architectural members and sculptures of the Parthenon’s many neighboring monuments.

Furthermore, the museum’s technological and organizational infrastructure became insufficient. It was under these circumstances that, in 1977, the Ministry of Culture, under the enlightened guidance of Academician and Professor Constantine Trypanis, proclaimed the first Panhellenic Architectural Competition for the erection of a new museum to house the treasures of the Acropolis.

It was clear that the new museum could no longer be built on the Hill, due to lack of space, increasing pollution and the crowds of visitors. Today, the number of persons who annually climb the Acropolis has reached one and a half million. This means approximately 10,000 visitors on an average day during the high season. This fact alone made any idea of the existing museum obsolete.

Yet such was the proposal made by George Dontas, General Ephor of Antiquities and Director of the Acropolis Museum in the early 1970s. “Why should we sacrifice the existing museum?” he asked. Not only was there the huge amount of money required for a new project, but the museum’s space could be designated as ‘closed’, meaning nothing new can be added. Besides, he emphasized the very great risk which would be entailed inthe removal of all these antiquities to another place.

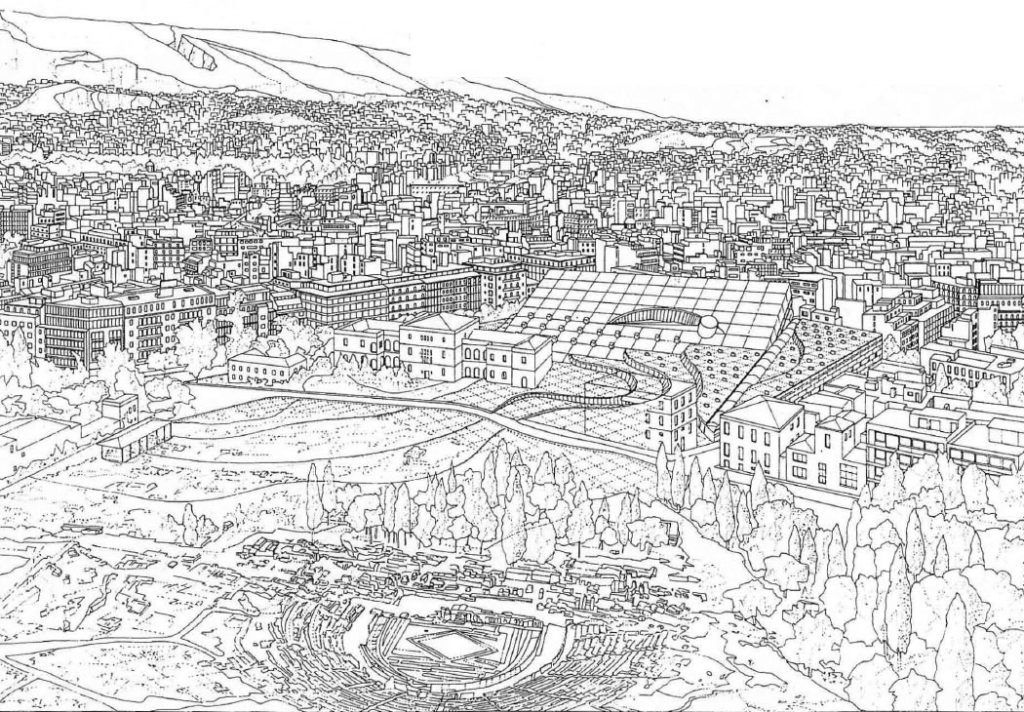

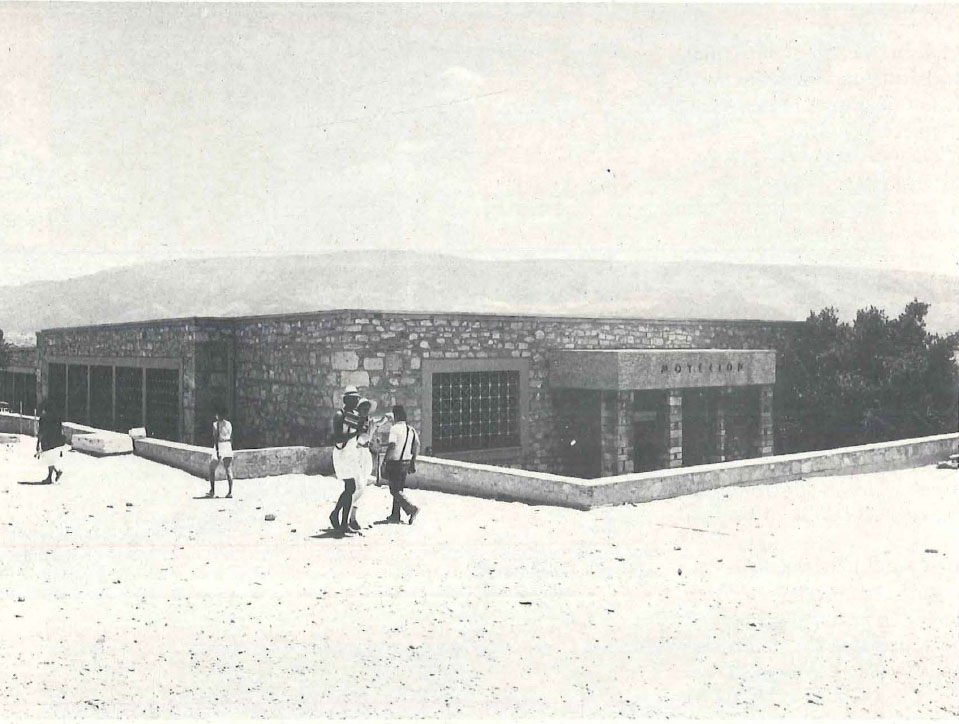

When the competition was proclaimed, the site that seemed to rally the majority of opinion, as being the most appropriate for the new construction was the Makriyianni Barracks and surroundings, at the corner of Makriyianni and Dionyssiou Areopagitou Avenues. The latter is the thoroughfare that passes in front of the Odeon of Herod Atticus just at the foot of the Hill. This large, handsome, three-storey, neoclassical building, known as the Weiler building, after its Bavarian architect, was erected in 1836 as a hospital. At the beginning of this century, however, its purpose was totally altered and it became the barracks of a gendarmerie battalion. In 1974, by the decree of Prime Minister Karamanlis, the whole complex was declared a protected building due to its historical and architectural interest. The gendarmes were removed and the building renovated by the Ministry of Culture.

During restoration, the original but concealed reddish stone of the exterior walls was revealed and, while work was being done on the surrounding grounds, an ancient road which probably led from the Theatre of Dionysos to the sanctuary of the same god was uncovered. Parts of a Roman mosaic and other antiquities were found as well.

Nonetheless, the 1977 Panhellenic competition had unsatisfactory results: no first and second prize were awarded. Two years later, however, a second Panhellenic contest was announced based on a modified building program, but still related to the Makriyianni site. Many controversial debates followed and the Greek Architectural Association reacted by discontinuing the competition. Two main reasons were given for believing that the contest was doomed from the start. On the one hand, the new museum was not placed in the context of a general replanning of the broader area around the Acropolis, and on the other, the size of the site was deemed totally insufficient. This second competition also generated no concrete results, and again no first prize was awarded.

In the meantime, the Makriyianni building was inaugurated in 1987 as the Centre for Acropolis Studies with a large display of plaster casts of almost all the Parthenon sculptures which survive today, and with contemporary administrative and photographic services. This is its current function. It happened that the inauguration of the Centre took place exactly 300 years from the date when Venetian admiral Morosini bombarded the Parthenon in which the Turks had stored ammunition, thus causing the devastating explosion which shattered the monument.

There has been no respite in the gradual deterioration of the Parthenon in the ensuing centuries. Pollution has transformed the marble into powder and the maintenance of many of its architectural and sculptural decorations have been attempted in the past using risky methods. Corrosive materials meant to preserve the building have furthered destruction.

So, in 1983, the Study for the Restoration of the Parthenon proposed the dismantling of parts of the monument reconstructed in the past and the further inclusion of scattered ancient pieces into their original positions. At the the same time, decisions were taken as to which of the parts of the different temples should be removed from the monuments and placed in a protected space. Once again, the erection of a new museum to house all these unique pieces of art became imperative and urgent.

As a consequence, in November 1986, Mrs Melina Mercouri, Minister of Culture, announced a new, now international, competition for the erection of a Museum of the Acropolis. The competition was to be under the auspices of UIA (International Union of Architects). The jury was also international, consisting originally of 15 members, seven Greeks and eight foreigners.

A new era was inaugurated. First, because the European Communities would contribute financially to the project, the contest had to be international. Then, the idea of limiting the site of construction to the Makriyianni block was questioned, provoking strong objections on the part of both specialists and common folk. They condemned the choice of the Makriyianni block as the worst possible, precisely because the Weiler building would be inappropriately included in the complex of the museum. Moreover, a great number of land expropriations are absolutely necessary in order to expand the existing area. There is also dense traffic at the Makriyianni junction.

It was at this stage that Professor John Despotopoulos characterized the Weiler solution as a ‘great insult’ to the Acropolis and expressed his fears as to the success of such a large building complex being constructed so close to the Sacred Rock. “Regardless of the ability of the architect, it would eventually lead to a superarchitectural creation.” It was clear that many people were apprehensive of adding a large construction near the natural setting of the Acropolis.

A committee of experts then proposed two alternative sites. Letters to newspapers and articles in magazines proposed still more locations and some bizarre solutions. Turmoil increased. The conditions of the Ministry of Culture remained clear: “the new Acropolis-Museum must be situated in an area close to the Acropolis in order that the inseparable bond linking the ancient objects with the classical monuments be maintained.” Because there were difficulties due to nearby building, traffic density and preserved archaeological areas, two alternate sites to the Makriyianni solution were offered. One was the north slope of Philopappos Hill where the Dionysos Restaurant is situated, including the parking lot and the green area opposite. The other was the Koile area on the west side of Philoppapos Hill, not far from the Dora Stratou Folk Dance Theatre, a large open space where, according to archaeological finds, there was a neolithic settlesment.

More than 1200 architects from all over the world submitted plans for the proposed new museum, with a total of 437 studies and models. But concern and fears as to the final solution has also come from abroad. At an International Symposium of Landscape Architects in Leningrad on the subject of “Protection and Restoration of Historical Monuments and Landscapes”, it was pointed out that “destruction of the historic landscaping which constitutes an indispensable part of the archaeolqgical Acropolis area described by UNESCO as a worldwide legacy” could create more problems for the Acropolis monuments.

According to the terms of the competition, the jury awarded 21 equal commendations amounting to four million drachmas each, and proposed that three other studies be granted three million drachmas each. Furthermore, ten studies were chosen to proceed to the competition’s second stage. The names were not published since the competition had not been completed at this stage, and, to maintain the compulsory anonymity, a public notary undertook all communications between the Ministry of Culture and the competitors.

One requisite for the architectural design was that the new museum must be a venue for the display of the Acropolis masterpieces in such a way that the visitor “may learn, study, participate or just enjoy the works of art.”

As regards interior space, the museum should include various exhibition areas and galleries displaying objects from prehistoric and geometric periods to classical marble or porous stone pediments, statues, votive pillars, vases and bronze statues, sculptural decorations, and Roman, medieval and Byzantine works. Facilities for visitors, including persons with physical disabilities, areas for cultural events, workshops, store rooms, administrative offices, and so forth, were to be provided.

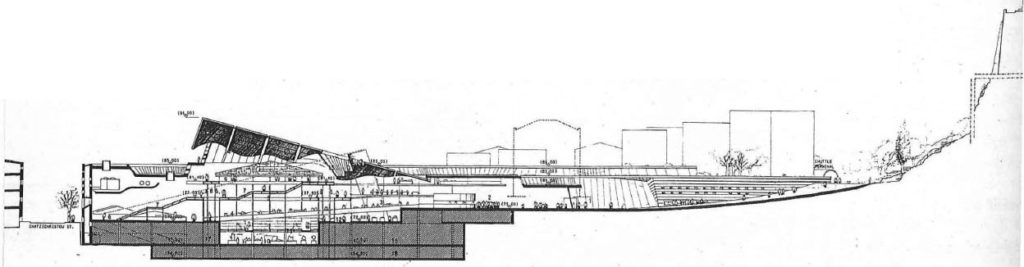

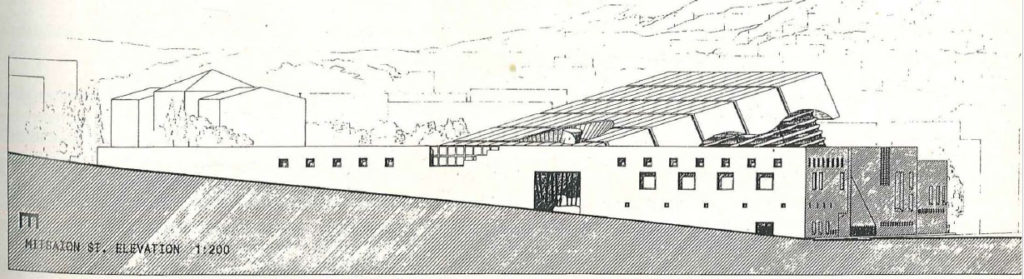

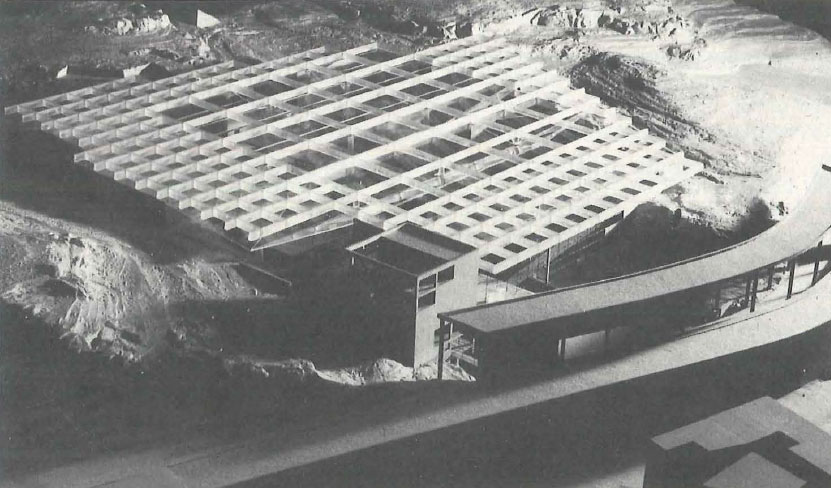

Finally on 9 and 10 November 1990, after detailed examination of each study, intense discussion, analysis and speculation concerning the architectural solution, as well as a lively exchange of opinions, the 14-member jury (the 15th member, the representative of the Greek architects refused to participate due to reasons mentioned above ) awarded the first prize (and 12 million drachmas) to the Italian team of Messrs Lucio Passarelli, civil engineer, and Manfredi Nicoletti, architect, and their collaborators. Their design, set on the most controversial site, the Makriyianni one, is called “An Open Eye to the Acropolis” because of a huge 40-metre-wide window on the roof, through which the visitor, wherever he is in the museum, has a view on the Parthenon.

The Italian proposal is an impressive building on numerous levels, topped by a huge inclined roof. The interior has long wide corridors at different levels where the antiquities are displayed in such a way that the visitor passes consecutively from one era to another. In the middle of this ‘promenade’, there is a space of the same dimensions as the Parthenon where the pieces of this monument will be installed (including space for the so-called Elgin marbles for which Melina Mercouri has created such a stir). Furthermore, there will be a transparent floor through which underneath workshops will be seen.

During his latest and third trip to Athens, Mr Lucio Passarelli told us: “I came to prepare the contract and examine the designs with the archaeologists. They appreciate what we have done and there will be only a few alterations because our designs are flexible.”

In reply to a question regarding the statement in Le Monde that 45,000 square metre project surpasses the 20,000 square metres allocated by the Ministry of Culture, Mr Passarelli pointed out that the excess area will be for parking. “We respect what the law says, and the space of the museum we designed is in compliance to what the Ministry asks” he said.

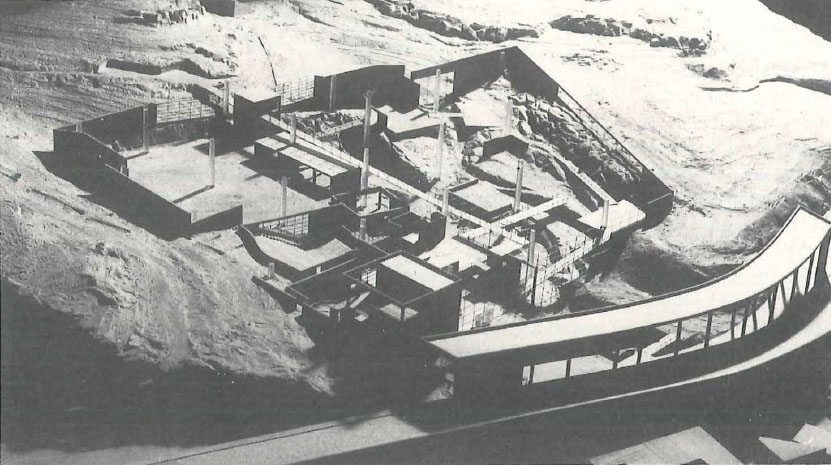

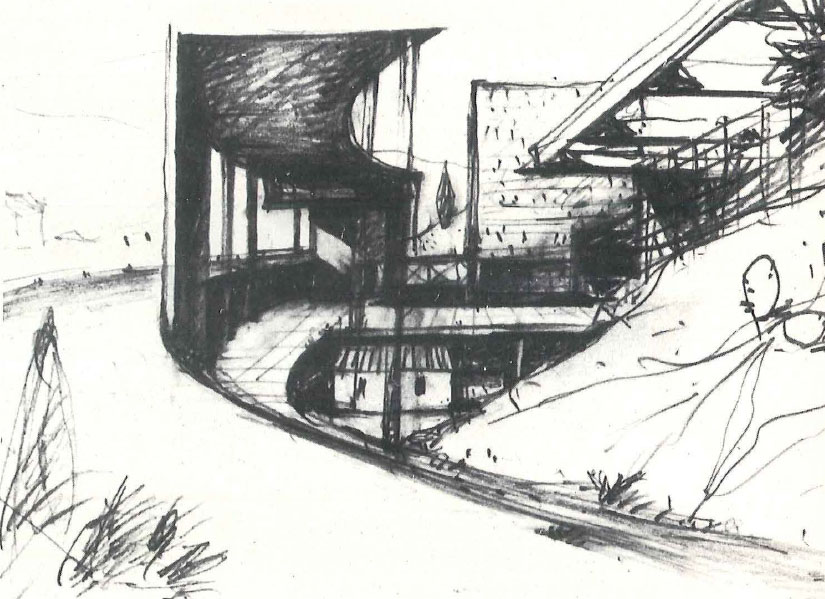

The second prize of 10 million drachmas was awarded to the team of Greek architects, Messrs Anastasios and Dimitris Biris, Panos Kokkoris and Eleni Amerikanou. They designed their museum for the Koile site incorporating the rocky ground and walls of the site as they are.

“We chose Koile because we think that there is a mental perception and not an optical one with the Acropolis,” Mr Anastasios Biris explains. “In this way. there is no confrontation with the Sacred Rock. On the other hand, the Koile site has an intensive historical past, it was alive at the same time as the Acropolis. On its rocky sides there are ancient cuttings. Furthermore, the shape of the Koile is a natural receptacle and we designed the museum in such a way to safeguard the grey rocks of Attica and let the Attic landscape itself enter into the museum. It seems like an archaeological excavation. We tried to give to our design the simplicity and the harmony of ancient monuments, exactly because we wanted to keep the Greek identity. And what is more important, there is a material connection between the displayed items and the interior of the museum: the marble and the stone.”

Third prize amounting to eight million drachmas was awarded to an Austrian team of architects under the name of Mr Abraham Raimund. They used the Makriyianni site and designed a modern building, .lower, than the Weiler one, functional and employing mainly underground space.

Now that the competition is over, real problems surface. The economic issue comes first, since the cost of the new Acropolis Museum is estimated at about 80 to 100 million dollars. Of course, help from the EC is expected and there is an important legacy from Ourania Hadjikyriakou of about 20 properties donated for that purpose. Other individual bequests are also expected. But the necessary expenditure is enormous and its biggest slice is the approximately 150 houses and apartments situated behind the Makriyianni site and on Dionysiou Areopagitou which must be expropriated. This is one of the strongest arguments for the opponents to the Makriyianni site solution.

Mrs Evi Touloupa, archaeologist, former Director of the Acropolis Museum and member of the competition jury declared that “Many years have passed since the matter of expropriations had been decided on and the competent authorities should have proceeded then, but they have delayed. Besides, there are many proprietors who want to sell their properties.”

“On the other hand,” Mrs Touloupa adds, “archaeologists and ecologists agree that there are no other large enough grounds near the Acropolis.

Furthermore the Makriyianni location is not situated on any green or archaeological space.” She characterizes the ‘Italian solution’ as a brilliant one and thinks that it is absolutely necessary that the museum be large because, aside from the Acropolis treasures, there are plenty of others in the area around the Rock which have to be protected, too. Mrs Touloupa concludes, “The Acropolis Museum is an absolutely urgent matter, and the scientists who work on the Acropolis are strongly concerned by the archaeological items which are in great danger due mainly to the pollution.”

“It is an interesting architectural construction notable for its flexibility” points out Mr Petros Kalligas. Head of the Ephoria of Prehistorical and Classical Antiquities and Director of the present Acropolis Museum, referring to the Italian project.” On the first floor, the sculptural parts of the Parathenon will be viewed by the visitor from an angle identical to the one of the ancient watcher of the Parthenon up the hill.”

As regards the opposition of the Greek Architectural Association, Mr Kalligas is of the opinion that they should defend their opinion by open debate, as they would in the Ancient Agora. Besides, as he says, many Greek architects took part in the competition. Negating the results of the International Competition makes Greece the laughing-stock of the international community. And he goes on to say “We have a substantial as well as a moral obligation to protect the sculptural pieces that are taken away from the monuments and display them in a safe place for one or two generations, as long as the pollution exists. Maybe later it will be possible to put them back in their original position.”

Mr Tzannetakis himself holds strong opinions on the expropriations: “Being obliged to chase people away from their homes pleases nobody, least of all me. But, when facing the dilemma of either proceeding with the Museum, a building that shall adorn Athens and shall project the image of Greece internationally, or canceling the project in order not to proceed with the expropriations, I must, without any reservations, choose the first solution.” He adds: “Besides, every effort shall be made to see that the expropriations proceed in accordance with current values, so that the people concerned can purchase an equivalent home.”

The Association of Greek Architects, is expected to oppose the implementation of the project.

Moreover, eminent Greek architects and city planners, George Kandylis and Dimitris Fatouros, both members of the jury, have already expressed their objections as regards the first prize. It has been characterized by many, both experts and not, as a barbaric construction idea displaying wealth and technical expertise that is antagonistic to the Acropolis, mainly because of its size. “Italians,” an architect was heard to say, “see the Acropolis like tourists.”

The public shall be able to formulate its opinion on the occasion of the exhibition organized by the National Gallery of Athens this month.

The truth is that the Acropolis treasures must be housed as soonest possible and Mr Tzannetakis is adamant: “I most urgently wish the Museum to be finished by 1996.”