An oversized town of 200,000 inhabitants, hardly larger than present day Patras, Athens in 1922 seemed in many ways more like a provincial community than the capital city and commercial centre we know today. The Balkan Wars of the previous decade had taken their toll: the arrival of several thousand refugees had helped swell the population from a mere 100,000 in 1900.

Only the privileged few had electricity and most working class homes were still lit by oil lamps. Out of 1000 family dwellings, a mere 65 had water mains. Shortages were frequent; not surprisingly, since the city still relied on ancient wells and a hydraulic system dating back to the time of Hadrian. Telephones and motor vehicles were rarities.

In the wake of Greco-Turkish War ending in August 1922 with the sacking of Smyrna, Greece was in a state of advanced economic and political chaos. Between August and December 1922 alone, there were seven successive ministers of Finance.

High military expenses during the Balkan Wars and now with the disastrous end to the Asia Minor campaign, the state was left bankrupt. Meanwhile, the labor force had been severely depleted since a large proportion of the nation’s young men were, or had been, away fighting for the country and the ‘Megali Idea’ for the greater part of a decade. As a result, Greece’s predominantly agriculturally-based economy was sinking fast. The trade deficit was huge. In 1922, 40.6 percent of all agricultural products had to be imported. Although profits were being made, in industry, notably in food sector, products were of poor quality, management was disorganized, and production methods were old fashioned.

It was against such a background that, in the later months of 1922 and, to a lesser extent, in 1923 and into 1924, Greece had to open its arms to over a million hungry, ragged, destitute Greeks from Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace. Fleeing to safety and freedom, they were forced to leave behind a comfortable lifestyle and a privileged position in Turkish society and all but a few hurriedly packed material possessions.

After the three-year long Greek Asia Minor campaign, ill-conceived by Venizelos in the first place, and then doomed by the broken promises of support from the Allies, the last remnants of the Greek army evacuated Smyrna on 8 September, leaving it to the wrath of Kemal Ataturk and his irregulars. During the next few days, many Christians were massacred, and two thirds of the town was completely destroyed by fire. Only a handful of buildings in the Turkish quarter were left unscathed. Over 25,000 Greeks died, and the 200,000 or so survivors, along with thousands of Greeks from further inland who had followed the Greek army’s retreat, thronged to the famous Kai (from the French quai), Smyrna’s elegant seafront imploring help.

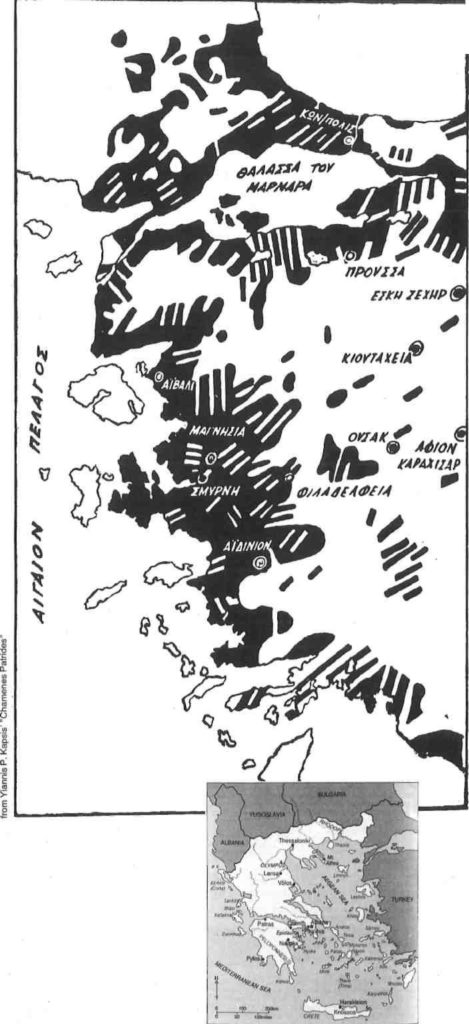

Thus ended 3000 years of Greek civilization in Asia Minor, and a period of self-sacrifice and struggle began for the Greek nation, one from which it would, however, emerge triumphant. The Treaty of Lausanne, signed in July 1923 and stipulating the compulsory exchange of Greek and Turkish populations, amounted merely to official sanction of a fait accompli, since by then nearly 90 percent of the total number of Greek refugees had already been, for the most part, violently expelled from Turkey. The Turkish populations of Macedonia, Epirus and the islands, however, were allowed plenty of time to pack and prepare for their departure. In fact only 150 to 200,000 refugees arrived after the treaty was signed, mainly from central and eastern Asia Minor.

Of the 1.5 million who added their number to a total Greek population of 5 million, 580,000 settled in rural areas, especially Macedonia and Western Thrace, 260,000 of these having come from Eastern Thrace. Many set about the arduous task of recreating the villages they had left behind. Approximately 350,000 families settled in or around the cities of Athens, Piraeus and Thessaloniki. The 1928 census recorded 144,895 refugees in Athens out of a total population of 488,870, or 296 per 1000 inhabitants. In many of the new refugee areas such as Nea Smyrni, Nea Ionia, Kaisariani, Vyron, Nea Filadelfia, Peristeri and Kokkinia, refugees made up to 95 percent of the total population. The death rate among the refugee population was, however, extraordinarily high the first few years of settlement: between 1923 and 1925 the ratio of deaths to births in Greece was 3:1, and in some parts of the country 20 percent of the refugees died within a year of their arrival. Other exact number of refugees who were living or saying in Athens in 1922-23 remains unclear.

In September 1922, Colonel Nicholas Plastiris and a group of officers seized power in Athens. Among the immediate priorities of this new revolutionary government were the provision of food, first aid and medical care, some kind of shelter and clothing for the ragged, destitute hordes. Many of these, believing their misfortune to be merely temporary, were convinced that they would eventually return to their homes. Most people brought their house keys with them, and there are stories of old ladies worrying that they had left the shutters of their houses open. Other, more wealthy, immigrants refused to accept any compensation money from the government on the grounds that do so would amount to official acceptance of their loss. Such misconceptions well suited the government since they justified the absence of a properly organized program of rehabilitation. So-called ‘short term, temporary measures’ soon became long term and semi-permanent.

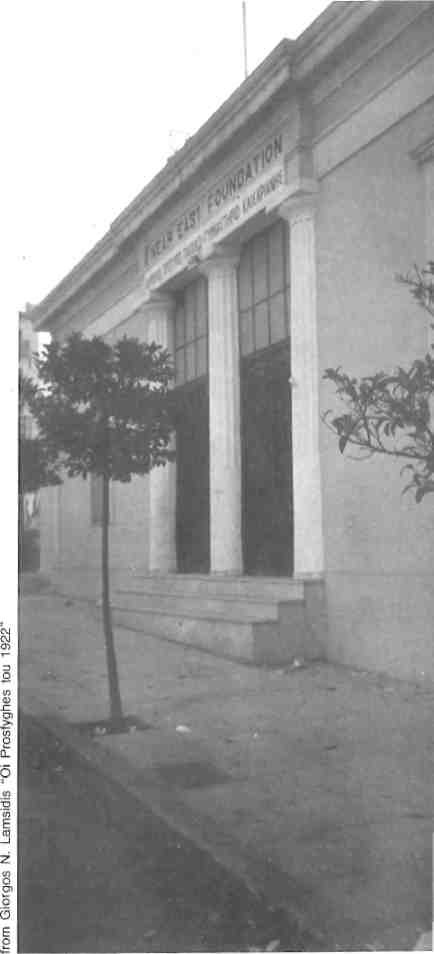

In dealing with the immediate problem, the government received much support from private enterprise and from foreign charity organizations such as the American Red Cross and the British Save the Children Fund. In Athens, refugees were provisionally sheltered anywhere and everywhere from what was to prove a cruelly cold winter. Many public buildings were transformed into dormitories: schools, churches, monasteries, public baths, theaters (in the Athens National Theatre, one family occupied each box), army camps, factories, warehouses, basements and stables. Tents and hastily erected shacks sprang up wherever space could be found, in parks and squares, beside roadways and railway lines, among the ruins of Olympian Zeus and the Agora, on the banks and even on the beds of seasonal rivers like the Kifissos and the Ilissos. As a result of the latter, not only were many flimsy temporary homes swept away by flash floods but several lives were lost as well.

In the months following the mass exodus from Asia Minor, the government tried to ensure that each refugee had a roof of some sort over his head. All over Greece, unoccupied land and buildings were expropriated by the state to accommodate refugees for a limited period only, without affecting rights of ownership (at least in theory). In Athens, over 8000 empty houses were expropriated, and if a house was judged spacious enough, wealthy families were compelled to accommodate refugees in their own homes. This enforced cohabitation proved to be just one of many sources of friction between native Greeks and the newcomers: people no longer felt masters in their own homes.

There was, moreover, a clear clash of cultural and ethical values between the two groups. For the refugees, who had always held Constantinople as their central point of reference rather than Athens, the Greek capital seemed disappointingly unsophisticated, if not backward, compared to the lively, cosmopolitan Smyrna and the other Asia Minor towns. To them the locals appeared narrow-minded, ignorant and uncouth, and plagued by a sense of national inferiority (which can be said to still exists today).

In Greece, besides, there existed a chasm between the educational level of the town dweller and the country dweller, something completely alien to those from Asia Minor, where even the remotest Greek village had its own well-stocked library and a school for both boys and girls (at a time when education for girls was frowned upon in Greece).

Conversely, there was a feeling among the native Greek population that too much was being sacrificed for the sake of those dirty, semi-Turks. Out of 1000 inhabitants of Greece in 1930, 31 spoke Turkish as their first language, while many more were bilingual. The fact that the majority of these were old men, or women or children (many of the younger men having been lost during the disastrous campaign) only served to heighten the feeling that the refugees were placing an intolerable burden on the already poverty-stricken state. Prejudice against and exploitation of the tourkomerites was not common, and women warned their children to eat up all their food or ‘the refugees’ would come and run off with them!

In November 1922, the Refugee Relief Fund was established whose function was to build houses for the accommodation of refugees throughout Greece. During its period of operation (up to May 1925) it provided 4000 houses in Athens with another 2500 under construction.

The areas it selected for development – Kaisariani, Nea Ionia, Vyron and Kokkinia – were on the outskirts of the city at the time and sadly lacking in basic facilities. There were no surfaced streets nor connecting roads with the city centre and no electricity. Drawn from the few local private wells, water was sold by the canful, and open drains ran down the middle of the roadways. The Relief Fund’s failure to deal with such problems adequately, coupled with terribly cramped living conditions (one family frequently having to make do with one room), meant that diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria and trachoma were rife.

The Ministry of Welfare at the same time had developed its own three-year construction program, contracting out construction work to the lowest bidder. This unfortunately meant that many of the houses were shoddily built. Throughout Greece, 22,337 houses of various types were constructed, from wooden shacks (theoretically short term accommodation), to handsome mud-brick two-storey houses. The majority were, however, small wooden constructions which seemed horribly confined and squalid when their inhabitants remembered the comfortable, clean houses in their former home towns.

Yet another social service agency, the Committee for the Rehabilitation of Refugees, was set up with the end of providing a more permanent type of accommodation. After initial doubts as to the suitability of Athens and Piraeus for further development, a new building program commenced in the four main refugee quarters of the capital, each of which were by now real towns of 20 to 30,000 inhabitants. By 1926, 9347 solid new housing units had been constructed. These mainly detached houses were built either of baked brick, a kind of wattle and daub, or flimsy panel board. Normally they were divided up into four separate households of 36-square metres, comprising a small hall, bathroom and two other rooms, one of which was used as a kitchen. The roofs were usually made of tar paper, which was later replaced by tiles. The houses were often very poorly insulated, and with their paper-thin walls, offered very little privacy.

Especially at the beginning of the building project, there was no standard type of house – some were bigger and better situated than others – and it was a matter of luck and political influence who got which house. In 1924, for example, 1000 refugees who were somewhat reluctantly moved from their warm temporary accommodation in public baths at Phaleron into large hospital tents in Kokkinia, before being allocated· their new homes, took matters into their own hands. One stormy night they broke into the not quite finished houses and occupied them. Similar incidents occurred in Kaisarlam.

Surprisingly perhaps, when one looks at Athens today, it was not until the late 1920s that a law was passed permitting the sale of separate flats in the same building. In 1932, the first municipal blocks of flats for the housing of the underprivileged were started in Leoforos Alexandras, comprising 200 residences of one, two or three rooms, a bathroom and a kitchen. Some of these still stand across the avenue from the Panathenaikos Stadium. During the 1930s several similar blocks were built in the refugee areas.

The impoverished state, then, managed, albeit somewhat haphazardly, to provide shelter for a lucky few, but by far the largest group of refugees were left to their own devices concerning accommodation. A wealthy minority, who had managed to transfer their fortunes to Greece before the catastrophe, established themselves comfortably in the city centre, but the destitute (about one million people nationwide) had nothing to fall back on but their own ingenuity. For some, schools, churches and other public buildings became permanent residences. Shanty towns (tenekedoupoleis: tincan cities) appeared, usually in working class areas or next to the government funded housing compounds. Building materials ranged from fruit crates and old planks to empty metal containers. Needless to say, a blind eye was turned towards illegal building.

One Athens suburb which was spared most of the problems of infrastructure suffered by the other refugee

areas was Nea Smyrni. In 1923, a group of formerly affluent and influential members of Smyrna society established a committee, whose aim was to provide a solution to the housing problem. With Vassilis Papadopoulos, an ex-official of the episcopacy of Smyrna, as its driving force, the committee carefully chose the site of its new town: a sparsely populated area between Athens and Phaleron with spacious plots of land and a convenient road system. Colonel Plastiras, now prime minister, accepted the committee’s proposal and in a record time of 15 days expropriation of the area began.

The following year, the suburb was brought within the city planning area, future landowners were selected, and the building of well-spaced comfortable houses began, much to the fury of the previous landowners. Later, many refugees either sold or rented out their properties, so that today families of refugee origins are about half. A fund was created to deal with the lack of public services in the area, and very soon wide tree-lined avenues were under construction, earning the neighborhood something of a reputation as a ‘garden city’.

In fact, Venizelos, pandering to his supporters, had invited a prestigious French construction company to undertake an eight million drachma building project in Nea Smyrni, but due to the economic crisis, it had to be shelved. Nonetheless, the government did lend its support to several building projects in the area, such as the construction of the Nea Smyrni ‘Alsos’ (park) and the two central roads, Aghias Fotinis and Efessou.

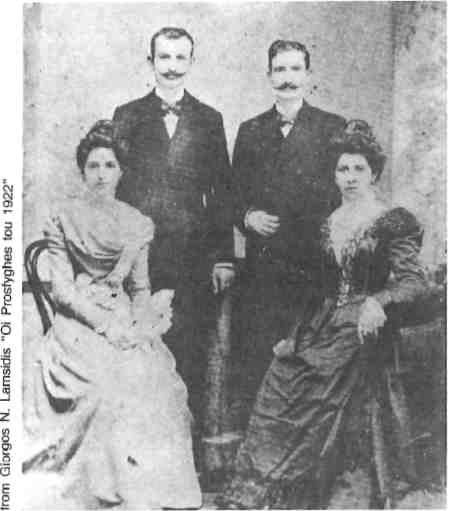

Greeks of Asia Minor enjoyed high education as well as a rich cultural life (Pontos, 1918)

Smyrna-style trio: Rosa Eskenazi with violinist Semsis and bouzoukdzis Tomboul

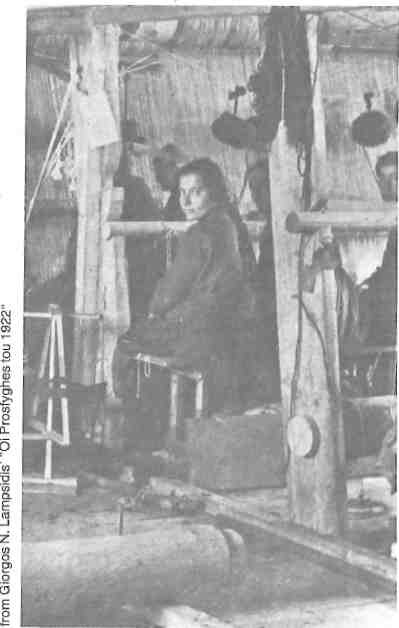

One bonus of sudden explosive growth was the boom in the construction industry. In this field, and elsewhere, the refugees provided a cheap, hardworking labor force, sometimes working up to 14 hours a day. Between 1922 and 1932, a proletariat developed in Greece for the first time. The work force in Greece increased by 175 percent, and women, who had enjoyed greater equality in Asia Minor society, began to work in larger numbers. In the same period, 690 new industries were established, giving a much needed boost to the depressed Greek economy.

In Asia Minor, the whole process of production, selling and transportation had been almost entirely in Greek hands. Of the 390 factories and workshops in Smyrna, 344 had been Greek owned, while 4500 out of the 6700 workers were also Greek. The same phenomenon was apparent in other Western Anatolian towns. Many banks, most shipping, import and export companies were Greek, too.

Once settled, many refugees used their compensation money from the government, or whatever they had managed to salvage from their lost fortunes, to set themselves up in trade. Their shrewd business sense more or less ensured them success. One textile company in Nea Ionia expanded from being a small workshop employing 30 women, into becoming a joint stock company with over 250,000 pounds capital and a work force of 2400 by 1926. Similar success stories abound. Other refugees, though destitute in terms of material wealth, made an incalculable contribution to the development of modern Greece in terms of expertise and commercial skill.

These new industries, which in turn gave impetus to established ones, included textiles (silk, wool and cotton), leather, Anatolian-style carpets, silverware, enamel, ironware, ceramics, tobacco, plastics and foodstuffs (especially tinned foods, confectionery and pasta). Between 1923 and 1933 annual national exports rose from 8 million pounds sterling per annum to 18.7 million, while between 1925 and 1929, industrial production rose from 4986 million pounds to 7157 million. Agricultural production also increased rapidly, as the incomers introduced new methods of farming and new crops.

Today, about 20 percent of the country’s manufacturing industries were founded by refugees: the Bosidakis group of companies (now state-controlled), Papadopoulos (the biscuit people), Biamax (motor vehicle assembly plants), and Kavounidis shipping, to name but a few – and the Onassis family, of course – also hailed from Smyrna. The remnants of many of the large number of small workshops (clothes, shoes, metal-welding, carpentry and so on) which were established can still be seen in basements and backrooms all over Athens, and especially in the traditional refugee areas.

Thus, in 1928, a mere six years after the disaster that many had thought would bring an already impoverished Greece to its knees, Venizelos was moved to speak of the “excellent human material” of which the refugee population was composed, adding that, despite the initial burden that had been placed on the Greek economy, the nation now had great reason “to look to the future with confidence.” In 1930, he even went so far as to discourage the Turkish prime minister, Ismet Inonou, from trying to lure the refugees back to Turkey, and a few years later he referred to the arrival of the refugees as a “blessing” for the Greek state.

Not only did the coming of the refugees revitalize the Greek industry, but it also greatly enriched Greece on a cultural level. Lying as it did at the crossroads between Asia and Europe and as the direct inheritor of the Byzantine tradition, it is not surprising that Greek Asia Minor enjoyed a rich and vivid cultural life. In terms of education, the Greek population in Asia Minor far outshone the Turks. At the time of the catastrophe there were approximately 2300 Greek schools with 200,000 pupils. Larger towns such as Smyrna, Constantinople and Trebizorfd boasted prestigious convent schools and institutes of higher education, such as the Evangheliki Scholi, the Theological School at Halki and the Megali tou Yenous Scholi.

Smyrna alone had five daily Greek newspapers and a number of magazines, a wide variety of clubs and associations, libraries, museums and theatres. In Athens, the refugees were quick to open up new cultural centres and societies, and to bring out new newspapers and magazines, most of which are still in existence. In 1930, the Estia Nea Smyrnis (New Smyrni Centre) was founded. Its imposing neoclassical building with library and archives, meeting hall and seminar rooms, remains an important cultural centre today. Over a hundred ‘homeland associations’ are still in operation, pub:lishing their own newspapers, organizing social events and nostalgic trips back to the lost homelands in Turkey, determined to preserve a sense of separate identity and a different way of life, though one cannot help wondering for how much longer they will continue to do so.

In Greek Asia Minor, the church had also been an important cornersto of community life, and, it is not surprising that, given the hardships the people had suffered and the fact that their religion had been used as a pretext for their expulsion from Turkey, one of the refugees’ first acts on arrival in Greece was to set up a church, in a tent, hut or whatever shelter was available. Later, as they moved into more permanent accommodation, the construction of a proper church was a priority, and collections for raising money were quickly made. In many of the new churches, the sacred icons salvaged from Asia Minor were placed. The building of one church in Kokkinia incorporated some stones brought over from its name’s sake in Nicaea, while the church of Aghia Fotini in Nea Smyrni contains not only the entire beautifully carved wood altarscreen, but also the bishop’s throne and pulpit which were carefully transported from the church of Aghios Ioannis Theologos in Smyrna.

In the sphere of the arts, the refugees have also left their mark. Greece’s first winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, George Seferis, came from Asia Minor, as did Ilias Venezis, Tassos Athanassiadis, Menelaos Loudemis, Kosmas Politis and many other well-known writers. They brought with them their distaste for katharevousa (purist) Greek, and introduced a wealth of new literary themes and ideas.

Musicians from Asia Minor, too, brought with them great technical skill, theoretical knowledge and professionalism, combining with them, quite new to Greece, a style of highly emotional and ornamented oriental music: the ‘Smyrna style’ as it came to be known. Cafes, of “which the most famous was the Mikra Asia in Pireos Street, sprang up all over Athens and Piraeus, where large groups of refugees played long improvised pieces for violin, santouri or voice: tsifteteli, aivaliotika, syrtos and menethos.

Working-class Athenians began to go out more often to listen to music, copying their new compatriots who were accustomed to the lively social life of Smyrna and Constantinople. Many features of the ‘Smyrna style’ were absorbed into rembetika music, too, especially the passionate tsifteteli, and female singers, such as Maria Politissa, Rita Arbatsi and Rosa Eskenazi began to perform with rembetika groups for the first time. Other refugee musicians, living as they did on the fringe of Greek society and being used to the legal smoking of hashish in Turkey, were attracted by the rembetika sub-culture and the hash-smoking dives, or tekes.

Asia Minor had also enjoyed a rich theatrical tradition, and such noted names as the late actor and director Karolos Koun, from Constantinople, the actors Dimitris Myrat and Stelios Bokavich as well as the great actress Kyveli, all from Smyrna, breathed new life into the Greek theatre.

At the same time, the names of many of Greece’s most successful football teams and sports establishments are testimony to the refugees’ determination to revive the clubs they had left behind. Panionios is a direct descendant of Panionios Smyrnis, founded in 1910, and Apollonas was also a well-known Smyrna club, while AEK (Athletic Union of Constantinople) and PAOK (Panhellenic Athletic Club of Constantinople) were both founded by Asia Minor Greeks.

Finally, any present-day taverna menu would seem terribly un-Greek without such staples as dolmades, tzatziki, soutzoukakia, briam, imam bayeldi, the yachni vegetable dishes, and many popular sweets such as baklava and kataifi have Turkish roots. As Asia Minor people and their descendants are very fond of saying, the Greek diet before their arrival was much blander.

“Before we came,” they say, “they used to live on bean soup, boiled salt-fish and greens.” Now, almost 70 years on, many of the refugees have long since passed away and the door keys to their beloved homes in Asia Minor have been lost. Prejudices have died too, and nobody speaks of the ‘dirty, half-Turks’ who, it was feared, would place such a burden on Greece – a fear which proved to be totally unfounded. But their spirit lives on, in Greek homes, at work and at play, on the streets of Athens, and Greece would be a very different, and poorer, place today without them.