At the time of World War I, it is said that about two million Greeks were still living in Asia Minor, and the historian, Kart Dieterich, was able to say then that this part of the world, more than all others, recalled the highest development of Hellenic civilization.

“When the powerful tide of the Turkish invasion, coming after so many other barbaric inroads, completely submerged Greek culture there”, wrote the University of Leipzig professor in 1918, “the Hellenic idea which this element represented was so strong that it survived everything. It was in vain that the fierce conquerors, as the tradition states, cut out the tongues of the inhabitants in order to cause this people to unlearn its language; it was in vain that they carried away their children to make of them fierce and cruel janissaries, who became exterminators of their own people. The Hellenic idea, the attachment to national traditions, was never submerged.”

A large and prosperous segment of this Greek population in Anatolia came from Pontos and, in fact, they constnituted the ethnic majority there. In the vilayet of Trebizond alone, the Greek population was about 350,000 in 1919.

The region of Pontos in northeastern Turkey extends along the southern coast of the Black Sea from Samsun to Rize, and is protected from the Anatolian plateau on the south by the Pontic Alps that run parallel to the sea.

Despite brutal waves of barbarous invasion and attempted subjugation, the Greeks of Pontos, in particular, preserved and perpetuated their native language and distinct regional dialect, their Hellenic culture and their Orthodox religion. Greek schools, often housed in churches and monasteries, were supported by the Greeks themselves, and were notable for their great number. In Trebizond in 1919, the Greek population supported about 250 Greek Orthodox churches, 95 Greek boys’ schools and about 11 girls’ schools. The annual pay at that time for a priest or teacher was about 500 dollars, by today’s reckoning. With essential supplementary costs for construction, repair and maintenance, along with salaries for supporting personnel, these costs were substantial and illustrate the degree of commitment and the passionate adherence to the Hellenic tradition.

A British officer on tour at the time said of these Greeks: “Profuse expenditure on education is a national characteristic, and to acquire a sufficient fortune to found a school or hospital in his native town is the honorable ambition of every Greek merchant.”

Ancient Trebizond or Trapezus (now Trabzon), best known of Greek Pontic cities, was surrounded by magnificent monasteries but the most exceptional, celebrated for its extraordinary setting and singular beauty, was that of the Panaghia tou Melas (Virgin of the Black Rock), popularly known in the Pontic dialect as Soumela.

Current Turkish guides highlight the monastery in their tours of Eastern Turkey. It is said to be the second most visited site east of Ankara after Nemrut Dagh, northwest of Urfa. It is also a cherished and nostalgic pilgrimage for aging Greeks who were born in Pantos.

On the Feast of the Assumption, 15 August, tourists, especially from Macedonia where so many Pontians found refuge, make the long and emotional trip back to their native villages and to the venerable old monastery. The silent cave church briefly comes to life with the chant of the Orthodox liturgy and the light flickering from the candles of indigenous worshippers, direct descendants of the ancient Pontians.

Soumela was founded to honor the icon of the Virgin, said to be painted by the Apostle Luke though recent studies have ascribed it to a later date.

The story goes that the icon one day turned up in Athens and expressed a wish to move on. It was transported by angels to a remote, blackened cave high in the steep Pontic Alps. Barnabas and Sophranias, devout Athenian monks, found their way to this cave, discovered the icon and established the monastery in honor of the Panaghia in 376, during the reign of Theodosius the Great. Other monks followed and it soon became the most renowned monastic community in Asia Minor.

Although innumerable political and theological disputes swept the whole of Pontos, the monastery remained steadfast, respected and powerful force until its calamitous demise in 1923 when the last monk was expelled. During long periods of heretical and infidel hostility, the icon was repeatedly reviled and abused, but every attempt to destroy it met with failure.

J. P. Fallmerayer, who saw the icon in 1840, wrote, “The Moslems tried to burn the icon, but it didn’t burn; they tried to break it with an axe, but it would not; they threw it into the stream, but it wasn’t carried away by the water … ”

It is believed that the existing crack in the icon is indeed due to the blow of an axe. Borne off by the last Greek refugees, the icon now receives homage in a new monastery also called Soumela built in the 1930s on a high location overlooking the Aliakmon River in Macedonia.

The route from Trabzon to Soumela cuts through a rustic, wooded Alpine valley. Heading south from Trabzon to Macka on the road that continues east to Erzurum, one climbs high over the Zigana Pass then descends to the flat, infinitely monochrome Anatolian plain. This path once was the ancient route for camel caravans conveying silk and spices from China and Persia to Trabzon where commercial Mediterranean fleets purchased their cargo and transported the goods to the west.

From Macka, a narrow mountain road begins the climb to the monastery, tracking the course of a wide, abundant river. Rotting wooden foot bridges sway in the wind and link hazelnut groves and villages lining the riverbed. Slender mountain streams appear like silken threads dropped haphazardly onto vast blankets of green hillsides and empty into the river below. Houses stand widely scattered and distant from one another, each surrounded by lush gardens and fields cultivated downslope, deep into the hills. As the road climbs higher into the mountains, the air becomes crisp even in the sweltering heat of mid-summer.

On the river banks; huge rocks, seven metres in diameter, create shimmering waterfalls. Towering fir trees sprout from these rocks, their spidery roots grasping the boulders like giant claws. Old poplar trees, ramrod straight, border the village fields where women harvest hazelnuts, tea, tobacco and maize. In the spring of 1990, the narrow mountain road was partially destroyed when heavy rains, battering . the Black Sea coast, broke down the escarpment onto the road, razing homes and buildings which last summer were still buried in mud.

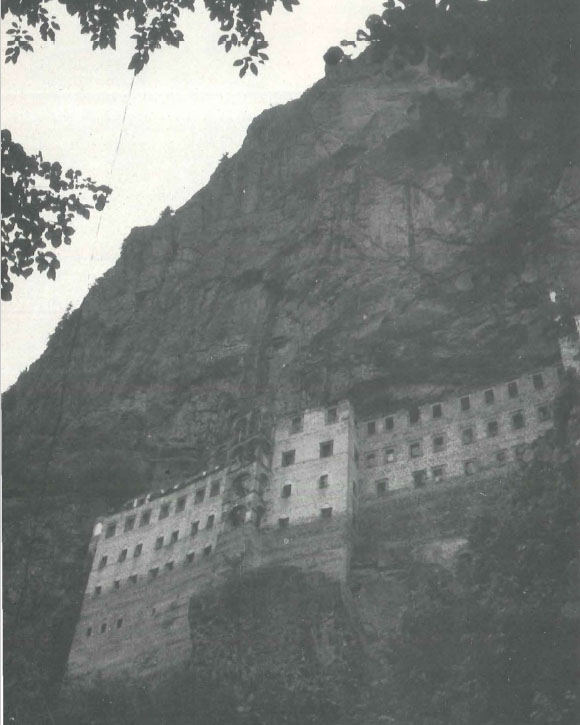

A small picnic and camping area marks the end of the road and the trail leading up zigzag to the monastery. The steep climb takes about 40 minutes. Halfway up, the hiker suddenly catches through the trees a first and indelibly memorable glimpse of Soumela. The seven-storey monastery clings precariously to a 400-metre vertical mass of rock so high that its peak disappears in mist.

Soumela is intensely solitary, secluded, wrapped in ·its own darkened al)d primeval womb. In setting it is . comparable to Mount Athos and Meteora and Delphi where majesty of place transports the visitor out of this world into contemplation of another.

Though what remains of the facade dates from the 1800s, the existing buildings were built around the 12th century. These include the original cave church, the steep stone stairs that ascend and then descend to the entrance, the inner court which once contained the kitchens, an enclosed chamber used for heating and giant water tanks which collected the natural mountain streams trickling through the rocks. On the arched doorway of tlte library the word ‘Bibliotheka’ is still clearly visible. Remnants monks’ cells or guest rooms can also be seen. Magnificent frescoes, some worked in gold, once covered every surface of the monastery, both inside and out.

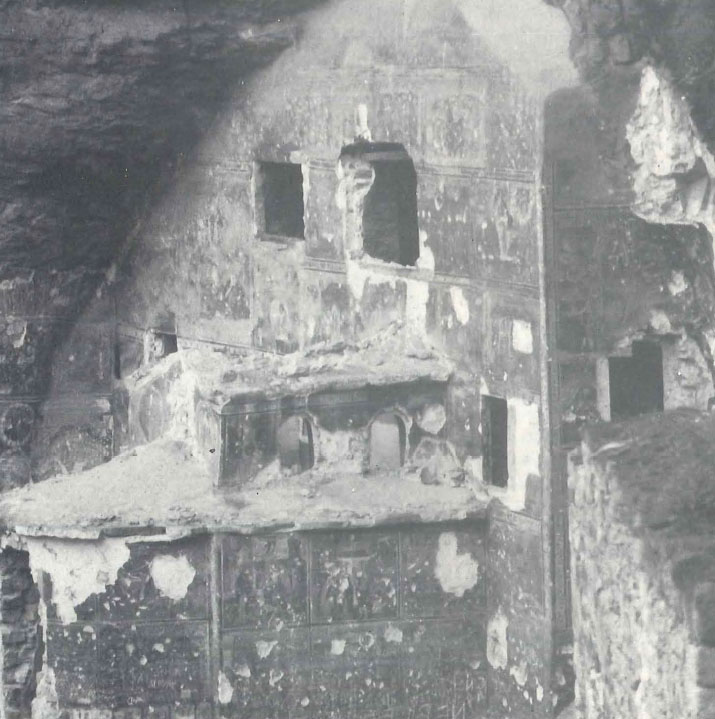

Lying in three layers, one atop the other, they date from 1710, 1740 and 1860. The monastery was burned just after the expulsion of the monks in 1923, and all structures made of woodbalconies, workshops, storage shelters – were totally destroyed. The degree and manner of irreparable and ongoing destruction is startling.

Whole sections of frescoes have been removed from their surfaces and hustled out of the country for profit.

Faces have been a particular object for defacement and are gouged out and pitted with rocks or bullets. The beauty of the paintings and the callousness of the damage are a jarring incongruity.

Some frescoes are etched out from edge to edge with the names of vandals and the dates on which they left their mark. Dates noted last summer were as recent as the prior week. Alas, no effort is made to protect this priceless art. Except for a weary gateman at the entrance who sells admission tickets in a small shed warmed even in summer with a small wood-burning stove, there is no guardian at the site.

The paintings adorning the walls and ceiling of the cave church are in a sad state of ruin as well. Those that remain and are still recognizable include a series depicting Adam and Eve. In one scene a naked Adam reciines, conversing with God. In another view, Adam and Eve stand in shame, with fig leaves, beside God. Elsewhere, a bold fresco depicts Saint George slaying the dragon. Despite the extensive damage, the sheer quantity of paintings on all available surfaces arid the vibrancy of their colors are still overpowering. In some sections of the interior, layers of more recent plaster have fallen away’ exposing older’ exquisite wall paintings.

In one place to the right of the entrance, a magnificent Panaghia and Child sit on a throne of gold, her gaze direct and unavoidable. It becomes apparent in this remote place, and in the Pontos generally, how the Pontic people were able to preserve their dialect and national fervor. They lived in a unique insularity that encouraged their interdependence and limited their assimilation from abroad.

Indeed, the dialect of Pontos has been the subject of great scrutiny in the study of modern Greek. The introduction of early Ionic forms, the growth of the language during the Middle Ages and the use of Byzantine words unknown to common Greek today have made it quite distinctive. Pontic Greek also absorbed many nouns, verbs and adverbs formed from Turkish words.

Its protective geographical place between the mountains and the sea separated the people of Pontos from the great masses of Greek people elsewhere in Asia Minor. During the spread of the early Church, Soumela and its surrounding area became a powerful religious centre. Many exceptional churches were built, such as Panaghia Chrysokephalos, Saint Eugenios and Aghia Sophia. All were converted into mosques after the Ottoman conquest.

The monastery connected with Aghia Sophia was originally built in the 13th century. During World War I it was used as a military infirmary. Today it remains the best preserved and most significant artistic and cultural achievement in the area of Trabzon. Its ‘fine Byzantine paintings are being stripped of layers of whitewash and restored to their original beauty by the University of Edinburgh. Since 1964, Aghia Sophia has been a museum.

Countless monasteries sprouted from the hills surrounding Soumela, many of them also expanding from simple mountain caves. Vazelon Monastery and Gregorios Peristera remain but are rarely visited.

Soumela stands alone. Veiled in mystery and witness to the vicissitudes of Pontic life, it remains indomitable and unequalied. Although the monks are gone and the worshippers are distant and silent, Soumela remains firm as a poignant ‘vestige of a once vivid Hellenic dream.