However sad it is for any animal lover to confirm, Greece has been one of the European countries least inclined to having and developing an understanding of animals.

There is no tradition of serious animal keeping – even the game pheasant farms have obviously inbred all their stock – and the general attitude of the public towards animals is still far from favorable. Consequently, the traditional way of animal keeping is that of ‘song’ birds, nearly always confined in cruelly small, hand-made cages. This hobby of ‘keeping’ native species has been supported by parrot finch imortations from the early 1970s. Reptiles are scarcely ever imported, always infested with mites and worms, and are displayed by pet shop owners in order to attract people into their shops rather than for the purpose of selling them. A more dramatic change has developed since 1980, as contact with European countries has become more frequent and regular. It is from this time that bird-watching, an awareness of nature conservation and ecological problems have been commonly practiced, as well as some interest aroused on the subject of reptiles.

In contrast with their ancient ancestors, modern Greeks consider all reptiles, snakes in particular, as ‘repulsive vermins’ solely to be destroyed. Compiling what has been written about them in collections devoted to Greek customs, popular beliefs, myths or facts could fill several large volumes.

Since 1980 a very active society for the study and protection of Loggerhead sea turtles, the much publicized Caretta caretta, which nest on Greek beaches, was created and soon gained popularity under the guidance of pioneering Dimitris and Anna Margaritoulis. Some years passed until the Herpetological Department of Goulandris Natural History Museum (1984), the first of its kind, was formed which deals with gathering information on Greek dis-tributions, bibliographical service, conservation campaigns and contact with foreign scientists.

The first reptile keepers, and they were very few, started to practice their ‘hobby’ around 1985, and it stimulated an interest so ‘imitators’ had a permanent snake exhibition at the Athens Exhibition Centre in 1984-1985. Other snake ‘exhibitions’ of varying quality soon appeared in Thessaloniki, Rhodes and Piraeus. Of these, some clearly violated several EC rules since the animals were kept in glass boxes with just a little, fouled water and infrequent cleanings. Some tropical snakes belonged to species which are strictly protected and in danger of imminent extinction.

The status of most of the sought-after reptile species has changed in the course of a few years. Some of the once commonest snakes, like the extremely beautiful Leopard Snake Elaphe situla, have suffered local decline and became extinct in many areas due to illegal collecting. The most overcollected species, however, seems to be the Levantine Viper Vipera lebetina schweizeri, endemic on Milos, the adjacent islands of Kimolos and Polyageos, and Sifnos. This viper suffers considerable losses: over one thousand specimens taken annually from Milos alone. After the continuous pressure by a Dutch conservationist, the first arrest of a collector was made by local policemen. Although many collectors ask for permits at the Ministry of Agriculture each year, there is regular illegal exportation of specimens by individual collectors.

The localized character of many species’ distribution also poses a special threat in the case of the biotope that could be destroyed. The Common Chameleon, Chamaeleo chamaeleon, The Levantine Viper and some local sub-species of other common Greek reptiles are good examples. The Kotschy’s Gecko, Cyrto dactylus kotschyi, is widespread in Greece, and its many isolated populations scattered in the Aegean islands and islets offer a unique opportunity of study for those scientists who specialize in systematics. This also holds true for Erhard’s Wall Lizard Podarcis erhardii, Danford’s Lizard Lacerta danfordi, and the Cat Snake,Telescopus fallax. In recent years, much research has been carried out on the behavioral and ecological patterns ot Agama lizards, Agama stellio, both in the Central Cyclades and on Eastern Aegean Islands.

Meanwhile, a new species of Greek reptile has been identified. Until 1985, four species of vipers had been recorded from Greece: the Nose-horned Viper, Vipera ammodytes meridionalis, the best known and most widespread, the Levantine, or Blunt-nosed Viper, Vipera lebetina schweizer from Milos, Kimolos, Polyaegos and Sifnos, the Ottoman Viper, Vipera xanthina, from Thrace and found on almost all eastern Aegean Islands, and the very rare and localized Adder, Vipera berus bosniensis found only in a few areas of Epirus and along the Greek-Yugoslav border.

The discovery of a fifth species, Orsini’s Viper, Vipera ursinii, in Greece is important, but not unexpected because the species includes some local sub-species. Its geographic distribution is sporadic and includes a wide range of the species with selected, isolated populations reaching even to southwestern Turkey.

The first record of Orsini’s Viper was a photograph taken on Mount Tzoumerka east of loannina in spring 1980. The snake apparently was a Vipera ursinii. The photograph appeared in a mountaineering magazine and was referred to as a ‘common viper’.

In the 1984 edition of the yearbook Thracian Chronicles (Thrakika Chronika) there is a photograph of an Orsini’s Viper taken by Mr Yiannis Charalambides on Mount Lakmos. Both Tzoumerka and Lakmos, together with the Koziakas Mountains, are part of the huge Pindus complex which forms the backbone of Central Greece.

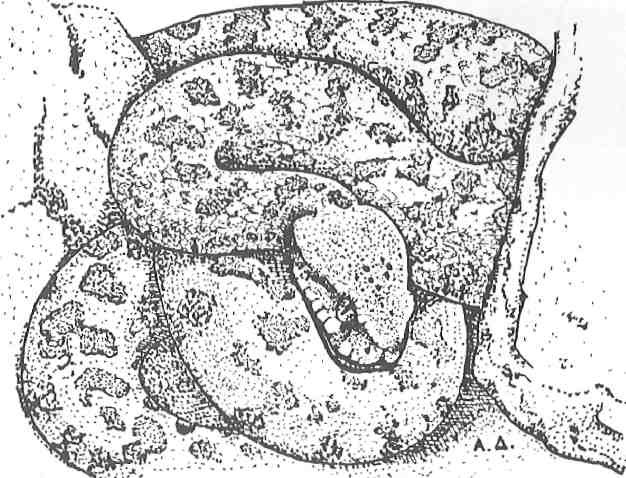

During the preparatory work for a reptile display in the Goulandris Natural History Museum, a systematic collection of specimens was made. Among other typical species of the Greek herpetofauna was a small unidentified viper collected in the Koziakas Mountains in spring 1982, The snake was found in a grassy meadow within the range of a hunting reserve.

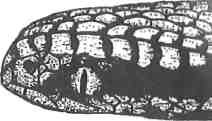

All specimens were photographed and sent to the Taxidermy Department of the British Museum (Natural History), London, so that casts could be made for display purposes. Later, the author examining the viper’s picture carefully, discovered a marked similarity to Vipera ursinii. Exact identification was not possible, however, since no scale counts were made and other morphological features had not been checked. A contact was immediately made with Dr E.N. Arnold in the Zoology Department of the British Museum as well as with Mr R. Hale in the Taxidermy Department. Finally, the snake was positively identified as Vipera ursinii by Dr Arnold who emphasized following morphological features of the specimen: the nostril is situated towards the lower edge of the nasal scale, while only one apical scale is in contact with the rostral. There are only about eight scales on top of the snout and the upper preocular contacts with the nasal scale. There are 19 dorsal scale rows at mid-body and dark edge to zig-zig vertebral stripe.

The presence of Orsini’s Viper in three neighboring mountain areas of Central Greece allows the quite probable hypothesis that the species is widespread on the Pindus mountain complex as well as on the mountains of Thrace (Rhodopi), where Vipera ammodytes, Vipera berus and Vipera xanthina occur. Each species is found in fairly different habitats while Vipera ursinii is a typical animal of mountain meadows or grassy slopes.

Far from being ‘repulsive vermin’, snakes are the destroyers of vermin and other pests. They are good scavengers and effective tillers of the soil. Their importance in medicine is greater than ever as the latest treatments for dis-orders like encephalitis are based on snake venom. The close relationship of Asklepios, god of healing, with the snake remains close. Today they are especially important as bio-indicators since an imbalance in the ecosystem is most likely to show up first when snakes diminish in numbers or vanish,”