The Greek people are religious in a peculiar way. Though they do not go to church often, their faith is deeply rooted. There is rarely a Greek home without its icons. Usually there are several of them, representations of the family’s patron saints whose names each member bears.

The word iconostasis (or eikonostasi) comes from the Greek eikon, meaning ‘look the same’ and the verb istamai meaning ‘to stand’. A showcase made of wood with a cross on top and the all-seeing God carved below, the iconostasis traditionally had, and often still has, a prominent household place. Apart from the icons of the saints, other symbolic things are kept here, leaves and flowers which have been used at special masses, ex=votos engraved with organs, dedicated to the saints in time of difficulty, a red-dyed Easter egg believed to bring fertility.

The iconostasis, together with the case containing the wedding wreaths, are, according to custom, hung on the wall above the double bed of man and wife. Nearby, an oil lamp flickers, kept constantly lit, its pale, pulsating glow filling and penetrating the bedroom with a mystic atmosphere.

All these are sacred things and play a vivid and intimate part in daily family life. Speaking to one of the saints through its icon when the need is felt to ask a favor or for help, or spilling some drops of oil from the lamp into the kitchen sink when the wind is high or the sea rough, are among the comforts which the iconostasis offers, for the blessed oil calms the excesses of man and nature.

Today the iconostasis may become the showcase for precious things, like traditional jewellery. The oil lamp may be wired for electricity and the icons moved into the reception rooms. This adaptation to modern life does not deprive the icons of their power. On the contrary, they have moved together with the family into new arrangements and the relationship remains: Greeks of all ages and social classes continue to feel that the icons are the mediums through which they communicate with the divine, and their relationship with icons remains strong. There is almost no young mother who will not pin up a small icon on the pillow of her baby in the cradle. Of course, another reason for the relocation of the icons to the salon is that if they are old family heirlooms, they have become valuable collector’s items and are worthy of being shown off. As such, and beyond their religious significance, they can become important parts of a dowry.

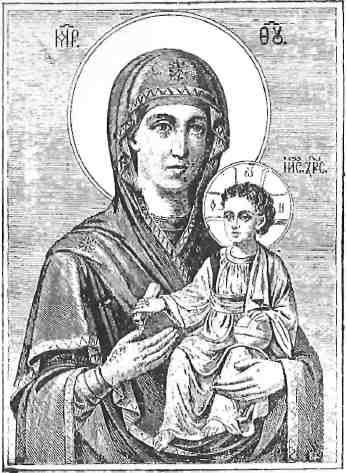

Even though iconography is a Greek word internationally used, it refers generally to symbols in the visual arts, while Greeks use the word hagiography in referring specifically to a holy picture. In either case, this particular art follows strict rules in order to fulfil its religious purpose and application.

By the prerequisites of the Eastern Christian tradition, not any picture of a holy person is iconography. Its chief purpose is to produce religious exaltation. It is not, in other words, an artistic display nor a challenge to aesthetic achievement. The antithesis of mannerism, the artist is enjoined not to show his skill. The significance of the icon lies beneath the surface and for that reason it is not easy to understand. Iconography must strengthen the faithful, instruct the uneducated and console everyone.

In the classical Byzantine tradition, iconography is not a realistic but a symbolic art. It expresses in line and color the theological teachings of the church. Moreover, the person who undertakes such a work, this special artist, is not just some who can display talent with a brush. As David Talbot Rice in Byzantine Art writes, “The mission of the iconographer resembles in many aspects that of the priest,” adding, “Even if the iconographer had seen a living saint, he would not paint him in nature but lit by Divine Providence… the aim was to carry the spectator away from the affairs of this world rather than to reproduce it before him.”

Since it is so closely and directly related to worship, the purpose of iconography is not to create pleasant sensations. In the past, most iconographers were either priests or monks who had their workshops in monasteries. Lay iconographers, while they painted, used to fast and pray.

It is interesting to note that due to this dedication to the theological mission of their work, the monks or priests who developed this art never signed their pictures. They truly believed that they offered their hand to Providence which then guided it. Sometimes they put their initials or added notes like ‘by the hand of a sinner ‘ or ‘by the hand of a slave of God’.

Through folklore, the accumulated insights of shared religious experience have woven around icons stories of their great and miraculous powers, innumerable and charming tales which reflect the deep bond between ethnic consciousness and its religious preoccupations.

There are, for instance, many stories which explain the choices of certain localities for churches, chapels and or shrines, always connecting them with the discovery of an icon. The icon sends out an assortment of signs, and most commonly the church must be built where the icon was found. Now, this in itself is not at all simple, since icons are

not found like the prizes at treasure hunts and paper chases.

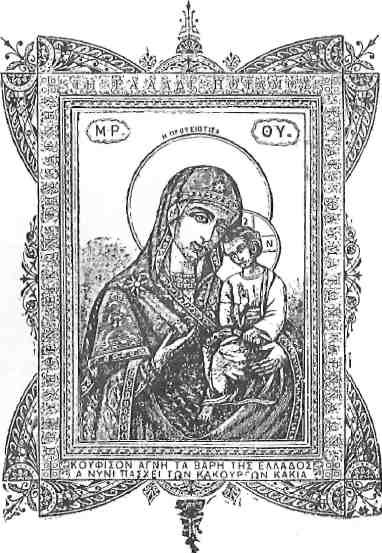

Many are the ways of deity in indicating where his icon lies. Knowing man all too well, he appeals to his senses: there may be a pale light shimmering in the night, or a distinctive and strange sound or the emanation of a delightful perfume. Usually, icons are hidden not only from the eye but from any rational means of inquiry, hence they are most often found by children or by people who are innocent. They are not exposed in open places, but are to be found in bushes, at the bottom of a well, inside caves, or even in dreams. By example, the great and miraculous icon of the Virgin on Tinos first appeared in 1825 in the vision of a nun.

The famous icon of the Virgin of Prousos near Agrinion first arrived there flying through the air at such great speed that it singed the vegetation around Kleisoura, the gorge lying just to the north.

Once the miraculous has entered the natural world, it becomes quite stern about following its laws, like cause and effect. The church must be built exactly where the icon indicates. If not, the place must be changed. If the construction goes on, the icon shows its disapproval and retaliates. This can be fatal. If placed improperly, the icon may move during the night, even ‘ if they tied it with a chain’. This has been tried and the chains were sundered like matchwood. To prevent a church from being built in the wrong place, the powers of an icon have even been known to hide the tools of the construction workers.

Sometimes an icon is found by a fountain or spring. In that case the water becomes miraculous and people come from far and wide to be cured and many who come halt – leave hale. But for all the miracles that icons work, it is the poetry that lives in the believers themselves which gives these places of worship, and their icons, their lovely names. The epithets attributed to the Virgin Mary, they say, are about a thousand. They indicate the place where her memory is celebrated or some special aspect of healing power: sweet-kissing (Glykofilousa), liberating (Eleftherotria), unfading rose (Rodo to Amarantho). If her place of worship is beneath a plane tree she is often Plataniotissa. Her chapel almost on the tracks of the electric train at Marousi is called Panayia Neratizotissa, Our Lady of the Bitter Orange.

On the island of Mytilene, the icon representing the patron saint Archangel Michael in the church dedicated to him is believed to be made from soil mixed with the blood of the monks of its monastery, martyred in a Turkish attack. It is also believed that the icon, on the eve of his nameday each year, leaves its place and visits the faithful. This is why a pair of iron shoes is placed in front of the icon ‘ since the saint in armor has an all-night march in front of him. ‘

At Limni on Euboea on the eve of the Virgin’s birthday on September 8, her icon is taken to the church of Saint Anne so she can enjoy a visit with her mother. This movingly reveals how people attribute the tenderest human qualities to these representations of their worship.

In Saint Nicholas, people venerate the Christian version of Poseidon, so he is the beloved saint of seamen. Ships carry is icon because sailors know that if it is plunged into a tempestuous sea, the waters will be calmed. This is reminiscent of the ancient Feast of Plyndiria when the cult statue of Athena on the Acropolis was carried down to Phaleron and immersed in the sea. The effigy of Artemis was likewise immersed at Taurus on the Black Sea.

Many popular Greek folk songs mention icons, and particularly beautiful verses describe the tears of an icon of the Virgin Mary on learning of the fall of Constantinople. It begins: “Be still, Our Lady, don’t cry. Dry your tears, for after a time, after years, all these things will be yours again.” In times of civic distress, icons have been often recorded to sweat, groan and even to crack, thereby showing their deep sympathy for the faithful. They warn him of approaching danger, too.

These beliefs seem to have been passed down to us from antiquity when, in procession, the effigy of some god seemed heavier or lighter, and so indicated the significance of the message the deity was sending.

It is a tradition, too, that an icon before it is first brought into a house spends 40 davs in church acquiring holiness.

The great importance attached to icons in Greek society is demonstrated in courts of law. For when the witness takes his oath next to the Gospel, there is the icon of Christ on which he places his right hand when he swears.

Witness to his conception, pinned to his crib, overlooking his class at school, heading the procession of his marriage, and set on his breast at his funeral, the icon is the life companion of the Greek.