In the chill pre-dawn hours of the 28 October 1940, all hell broke loose along the mountainous Albanian frontier as a mass of armoured vehicles and men poured across into Epirus and north-west Macedonia, their support artillery illuminating the already fading darkness; the Italian ‘blitzkrieg’ on Greece had begun. The invading troops (approximately 100,000 in strength) were well-trained, well-equipped and in high spirits, eager, once again, to prove their invincibility after months of waiting.

With most of Europe now under the fascist ‘new order’, they were certain that Greek morale would be low and expected only half-hearted, token resistance. General Visconti Prasca had assured Mussolini two weeks earlier that by mid-November the Italian flag would flutter over the’ whole of Epirus and that it would be only a matter of time until Athens, Salonica and the rest of Greece fell.

Daybreak, Monday 28th October 1940. All over Greece sirens are screaming in the cities, bells are ringing in the villages and islands; enthusiastic shouts are resounding everywhere, the shouts of a people whose centuries old tradition and legacy awakened that fateful morning in their heart and mind bringing back to life from the distant past Greece’s legendary passion for freedom.

C.N. Hadjipateras

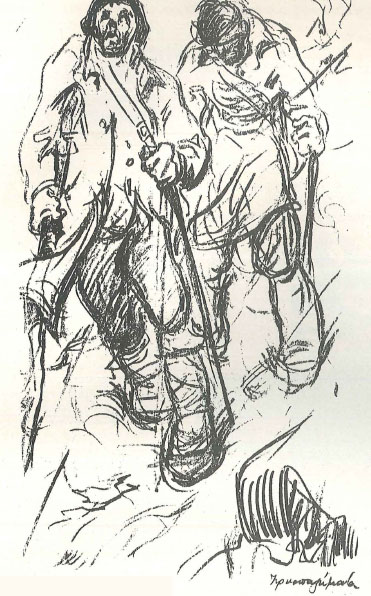

News of the invasion radioed through immediately to the Greek army camps strung out strategically across Epirus, some 30-40 kilometres back from the border, caused little surprise. The 40,000 odd soldiers (including local reservists who had been called up as early as May that year) were relieved that the war of nerves and propaganda was over and the stage set for the struggle against a numerically superior enemy to save their homeland and their honor.

For the next three weeks, while the world held its breath in disbelief, the Greeks, initially falling back under the sheer weight of the attack, routed the invaders on every front and unrelentingly pushed them back off Greek soil.

International press headlines ran out of superlatives and metaphors in a spate of almost delirious reporting as sensational communiques were relayed to the waiting outside world. The battle waged in the wilds of the Pindus mountains made front page news in countless languages, projecting the isolated village of Vovousa into sudden limelight, for it was there that the miracle, which the media worldwide dubbed The Modern Battle of Marathon took place.

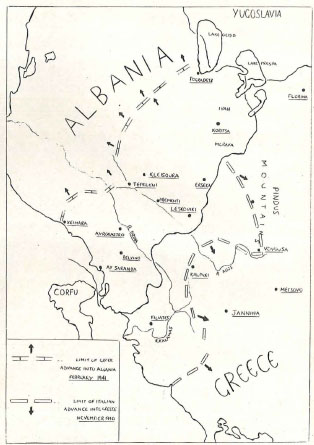

Seven select, much vaunted batallions of the Alpine Julia Division were balked in their advance towards Metsovo and the main roads running south, by two detachments (one battalion in strength) of Greek soldiers supported by raw conscripts, trained and baptised by fire at the front as they arrived, together with the staunch unflagging women and children of the mountain villages. Ill-equipped, ill-supplied and even ill-fed, fighting in almost Arctic conditions over savage terrain, the natural habitat of bear, wolf and jackel, their heroically stubborn resistance worsted the military pride of fascist Italy. Glorious history was being written near Fiorina, at Konitsa and Kalpaki (Elaia) where a junction of strategic importance on the road to loannina was held by Greek forces with almost maniacal courage and unyielding obstinacy despite continual heavy air attack by the powerful Italian airforce. At the Kalamas River near the coast, the defenders, after days of bloody fighting under constant bombardment by air and sea, were forced back along the coastal road. But here too, the assailants failed miserably to reach their Arta-Preveza objective, and were checkmated at a line running east from Parga.

One thing is certain and the whole world knew it: Greece neither wanted nor provoked that war. Even the foreign power which had committed the sacrilege, that is the torpedoing of the cruiser Elli in Tinos on the 15th of August 1940, one of the greatest Orthodox celebrations, was concealed from the Greek people, although it soon became obvious that the invisible and sneaky enemy had been the Italian submarine Delfino.

C.N. Hadjipateras

E – se tutto va bene Prenderemo anche Atene.

“We’ll go to the Aegean and we’ll take the Piraeus, and if all goes well, we’ll take Athens too.” Italian Army song

Mid-November, to the astonishment of Allied and Axis states alike, found the enemy army back where it had started on the Albanian side of the wintry mountainous frontier it had so confidently violated less than a month before. In horrendous conditions, the victorious Greeks, under the command of General Papagos, fought fiercely for every patch of ground, through rocky defiles, across raging torrents. Often thigh-deep in snow, they inexorably forced the Italians to continually retreat and regroup.

The Axis’ seat of operations in Albania and the general nerve-centre for the area was Koritsa, which sits some 2500 feet above sea-level dominating a large plain and is naturally fortified in the rear by the forbidding heights of the Morava and Ivan mountains. It was further defended by a vicious range of artillery and a seething mass of enemy troops, who, secure in their impregnability, confidently awaited the Greek units advancing towards them over the plain from the west. Other Greek forces had meanwhile crossed into eastern Albanian territory from north Macedonia, and braved the ‘terra incognita’ of the isolated Morava range. Struggling against both nature and the enemy, they advanced through blizzards and sleet in glacial sub-zero temperatures, suffering, as in other theatres of the war, from frostbite, hypothermia and snow-blindness, to emerge victorious down onto the plain, astonishing the garrison by appearing from the east.

Mussolini is above all indignant at the German occupation of Rumania. He says that this has deeply and adversely affected Italian public opinion. “Hitler keeps confronting with faits accomplis. This time I shall pay him back in his own coin; he shall learn from the newspapers that I have occupied Greece. Thus equilibrium will be restored.” I asked if he had reached agreement with Badoglio. “Not yet,” he replied, “But if anyone finds it difficult to fight the Greeks, I shall hand in my resignation as an Italian.” This time the Duce seems determined to act. Actually I believe the operation to be useful and easy.

Ciano’s Diary October 1940

The town was now surrounded and virtually besieged. Holding it were two crack Alpini batallions of the Trieste and Venezia Divisions, along with three others: Piemonte, Parma and Areggio, two independent battalions, two battalions of fanatical fascist ‘Blackshirts’, one of the famed ‘Bersagliere’, and light and heavy artillery units – a daunting force. For eight days a pitiless battle raged, but incredibly on the 22 November, Koritsa, for the fourth time in 28 years, fell once again into Greek hands. Massive stores of arms and supplies came as an additional, much needed, prize. Jubilant Allied leaders from De Gaulle and Churchill to President Roosevelt were lavish in their praise while Hitler wrote sourly to Mussolini , “I don’t dare imagine the consequences of the events in Greece.” One after the other, towns fell, like so many ripe plums, Erseka on 21 November, Leskoviki on the gentler Albanian slopes of the grim Grammos range the day after, Moschopolis on the 24th and, at the end of the month, the 30th, Pogradec, a town of ancient lineage on the tree-clad shores of Lake Ochrid.

The shameful defeats of a pointless campaign caused certain of the Balkan states to regard us with scorn and contempt. Here, and nowhere else, are to be found the causes of Yugoslavia’s stiffening attitude and her volte-face in the spring of 1941. This compelled us, contrary to all our plans, to intervene in the Balkans, and that in its turn led to a catastrophic delay in the launching of our attack on Russia… If the war had remained a war conducted by Germany, and not by the Axis, we should have been in a position to attack by May 15, 1941. Doubly strengthened by the fact that our forces had known nothing but decisive and irrefutable victories, we should have been able to conclude the campaign before winter came.

The Testament of Adolf Hitler

Throughout the bitterly cold month of December the Greeks still fought on, advancing along the valleys of the Aoos and Drina Rivers deep into the Albanian territory known to them as North Epirus. Premeti on the Aoos was taken on the 3 December and, two days later, further west, Delvino. On Saint Nicholas day, Italian propaganda suffered yet another serious blow when units reached the age-old, predominantly Greek, Ayioi Saranda on the Adriatic coast which Mussolini had renamed ‘Porto Edda’ in honor of his daughter, Countess Ciano. The following day, the picturesque district capital Argyrokastro on the River Drina fell with ‘minimal casualties’, its mainly Greek populations welcoming the victors. All alone the front which ran east-west right across the country, small battles were continually fought and won, prisoners and supplies taken, and the Italians ever pressed into retreat. Even a Japanese newspaper (Japan had signed the Tripartite Axis Pact the previous September) was moved to write “Our country which particularly honors bravery, is following with admiration the battles of the Greeks in Albania which so emotion us that, putting all other considerations aside for the moment, we shout Zito Hellas.”

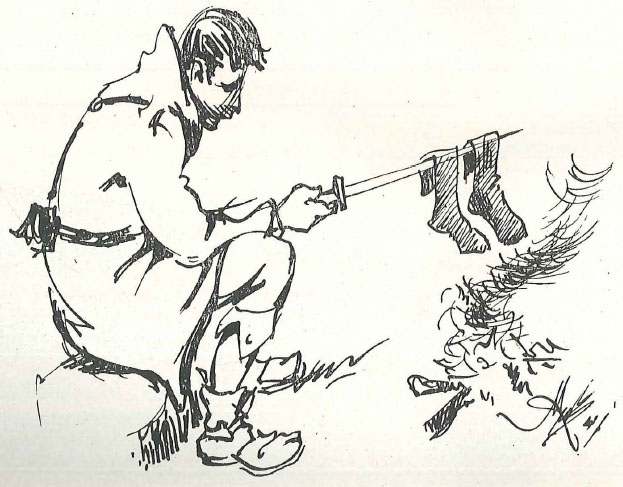

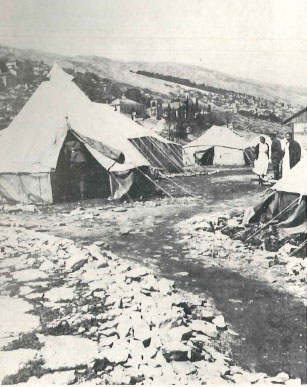

We sleep in short snatches. Turning over in bed to change position is normally done without waking completely, and in any case does not interrupt one’s rest. But turning over in the mud is an entirely different matter. One’s body, which in its wet clothes has made a warm hollow for itself, suddenly comes into contact with the rest of one’s cold, wet clothing, unless something still worse happens and it comes into contact with the pool of mud which has formed at one’s side.

Greek soldier’s letter home

During Christmas week the Greeks encircled Heimara on the Adriatic coast, a veritable fortress bristling with artillery and heavily defended by nearly a thousand men including the first Blackshirts battalion and were astonished when the whole garrison surrendered. Stockpiles of food, arms and ammunition made a welcome seasonal gift. The new year, 1941, was toasted in with optimism and heralded further victories round Kleisoura where the Italian-officered, Albanian Wolves of Tuscany Division presented unexpectedly tough and stubborn resistance. After a protracted bloody battle, the position fell on 7 January. Ten days later in the Kurveleschi highlands which were defended by a forest of redoubts, trenches, gunposts and strongholds they won a whole series of engagements. It wasn’t until February that the momentum of Greece’s glorious winter campaign slowed to a halt in the hills not far from the town of Tepeleni.

As a war correspondent I lived very many experiences which will remain part of myself for the rest of my life. But out of them all, none is more rich and wholeheartedly true than this one here: I had the invaluable privilege to work and live next to the Greek soldiers, and even sometimes share their dangers, to live with a people for whom freedom is the very breath of life and death just an episode.

Leland Stone Journalist

Mussolini, by now an object of ridicule, lampooned by cartoonists the world over , desperately threw fresh troops and massive reinforcements into the fie ld . The triumphant battle-weary Greek heroes, surviving on over-extended lines of communication had, by their astounding courage and fortitude in the face of such daunting odds, turned the tide of war giving the Allies their first victories, ably demonstrating that the Axis forces were no longer invincible. Now they could advance no more and digging in where they stood, they stoically held ‘”a line stretching from Heimara to just north of Kleisoura and on to Pogradec on the shores of Lake Ochrid.

If you were here with us now, you would feel very deeply, I’m sure, this extraordinary spirit which spread all over the country, two months ago, like a fire – the fire which says no to everything we hate, the fire of daring and purification.

George Seferis to Henry Miller 29-12-1940

Much apologist literature has been written in the intervening years in an effort to rationalize the overwhelming defeat suffered by the Italian invaders. But the plain facts remain that the fascist army was trained and excellently equipped and the men, whatever their poli tical beliefs, eager to extend the frontiers of their motherland, as the Popolo d i Roma’ had earlier rashly predicted, to the shores of the Black Sea. This grandiose and long-conceived plan as thwarted by the supreme valor and sacrifice of the ‘few’ Greeks on land and sea as well as in the air, and no amount of juggling with history can diminish their ‘finest hour’.

At school they had heard that it ~as a fine thing to die with a bullet in one’s heart kissed by the rays of the sun. No one had thought that one might fall the other way up with one’s face in the mud. Also there is the dirt; there is no hope of washing; beards are long and thick with mud, and uniforms are torn to shreds.

Italian officer’s letter home

Home-front means also putting songs to one’s country’s service. Sofia Vembo, the “singer of victory” as she was called, carries away the army as well as the whole fighting nation. Her fiery message gets even beyond the Greek boundaries. In England, Florence Desmond enchants her public with a song of Vembo, launched from the London Palladium’s stage in 1941 and: sung with enthusiasm by the entire audience of all ranks of British society.

C.N. Hadjipateras