In speaking of traditional Greek jewellery, we usually think of the period comprised between the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 20th century. Yet Greece, of course, has a long and remarkable tradition in gold and silversmithing reaching back to the spectacular craftsmanship of the Minoans and Myceneans, not to mention that of the Classical and Hellenistic periods whose refinements we admire in museums.

There was a zenith in the splendor and imagination of the jewellers’ art during the Byzantine period, mainly in work done for imperial families and nobility, as we can still see in the glowing opulence of the San Vitale mosaics in Ravenna. With the disruptions of the Crusades beginning in the 11th century, followed by the onslaughts of the Seljuk and Ottoman Turks, the art lost its bloom. With the fall of Constantinople, it all but vanished for several centuries.

Then, as if by miracle, towards the end of the Ottoman domination, the art blossomed anew into a burst of incomparable variety of shapes, forms and colors. This happened particularly in areas of Greece where a certain prosperity arose due to commercial concessions being made by Turks for cottage industries whose products were in demand in the west.

“Collecting these things is a passion, a kind of mania,” Katerina Korre-Zografou admits, “but it makes me happy because it gives me fulfillment, and to live among these beautiful things is an antidote to the ugliness that surrounds us.”

Mrs Korre-Zografou may have the richest private collection of Greek traditional jewellery in the country which certainly competes with those in our best museums. Truly she is a phenomenon, acquiring, as she did, her first piece while a student, and now owning over a thousand objects.

“During my student days, I earned some pocket money from private lessons and spent it buying the things you see here,” she says, looking around at them, then back at me, with her acquainted smile.

Her curriculum vitae fairly overwhelms. She is a professor at the School of Hellenic Folklore of the University of Athens. She is constantly producing books, articles and monographs in her field, or rather in her succession of fields, since jewellery is but one plot, and she reaps in all fields of traditional craftsmanship. She is also active in every sort of club and organization related to folkfore. She gives lectures, heads seminars, leads discussions, but wherever she is and whatever she is doing, simply, clearly, affectionately, she passes on her great and deep love of the Greek heritage to others.

She was born in Athens, but her great grandfather, Constantine Zografos, came from Constantinople, emigrated here and served at one time as foreign minister in the reign of King Otto. Mrs Korre-Zografou first studied at the University of Athens and then at Bonn where she concentrated in art history. Throughout these academic years, she has never stopped collecting.

In considering traditional jewellery, the preciousness of the materials is not necessarily an aesthetic criterion, being due mostly to circumstances, but the skills of the artisan and the wealth of his imagination certainly are. Nor can geography or date be of much help. Jewellery makers travelled a lot, and so did the women who wore them. In a world as precarious as Greece’s during the Tourkokratia, it was wise to have capital that was mobile, or as keepers of livestock put it, “investments that have feet.” Not much can be done with chronology when so few pieces are engraved with a date.

Nevertheless, grosso modo, we can divide traditional jewellery into two general categories. One might loosely be called ‘native’ since the pieces are mostly from the mainland, are crafted by Greek hands and are inspired by the Greek past from the mythological to the Byzantine.

Centres of this art are spread from Thrace in the east to the Epirot villages of Syrako and Kalarites high in the Pindus above Ioannina, and south to Lamia. At Stemnitsa in the heart of the Peloponnese, the tradition continues to this day at a school in the workshop of a goldsmith. Here in Arcadia, legend has it, that the skill of the artisans was so great that they could hammer out jewellery while riding muleback.

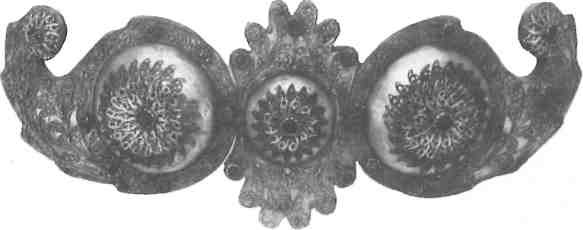

The second general category of traditional jewellery is of foreign influence and comes mostly from the islands. It is more refined, more meticulously worked, more often of gold and precious stones; pearls and enamel are common. The pieces were mostly brought from Europe by wealthy sea merchants, or, if locally made, still showed the influence of the Baroque style so popular in the west. Many of these pieces are called venetika either because they came from Venice or were molded from melted down Venetian ducats, the famous ducato d’oro.

The materials of mainland jewellery, which mostly concerns us here, were not so precious. The purest silver used, called lagara, was clearly stamped as such. More common was agiari, 400 parts silver to the kilogram. In order to give silver alloy the appearance of purity, it was often whitened with arsenic powder, hence the name fannakera from the word farmako (pharmacy), meaning drug or poison. It was also very common to gild silver jewellery.

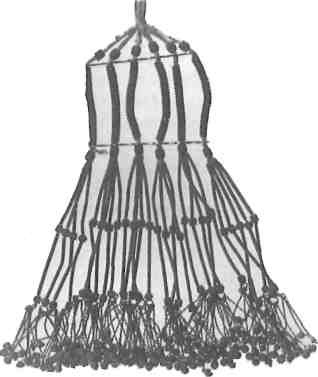

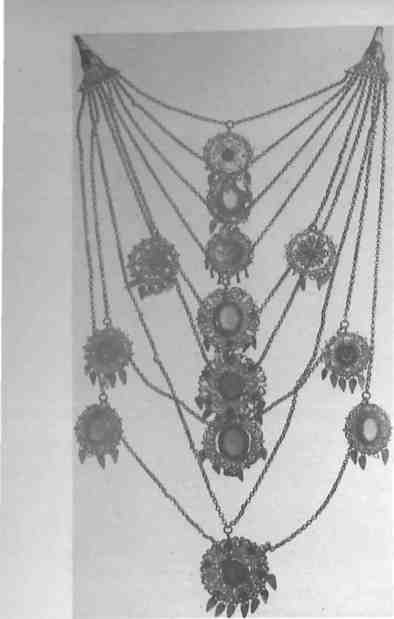

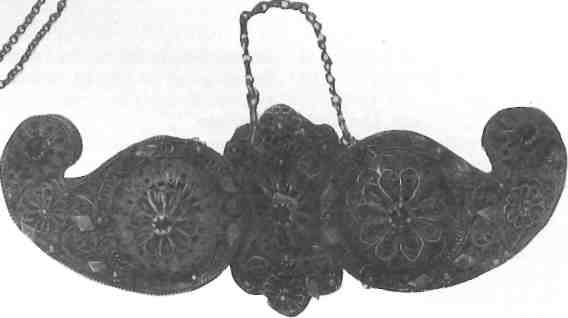

All types of traditional jewellery were decorated with multicolored stones, not necessarily precious. Agates, pieces of coral, and bits of glass in striking hues gave beauty and variety. Design was symmetrical. Following the symmetry of the human body was a rule of popular art, and there was a folk belief that the strict repetition of the same design gave power to the bearer. Men certainly decorated their firearms and martial appurtenances, but body jewellery – the decoration added to costume – was worn almost exclusively by women. Men might wear them on special occasions, like the groom who in some villages wore a belt decorated with coins. In some areas, however, there was a specific item of jewellery that was worn by women and men. This was the heavy, complicated costume piece called kiousteki, from the Turkish kostek meaning watch-chain. Decorating the chest, they are bulky items combining many techniques.

These kioustekia, Mrs Korre-Zografou explains, especially during the last period of Ottoman domination, were created as a deliberate element of ostentation showing off one’s wealth or social status or even proclaiming a kind of defiant independence from the Turks, particularly when worn by klefts.

On the subject of kioustekia, Mrs Korre Zografou adds parenthetically that they show a striking resemblance in shape to the ceramic and copper decorations of the sixth and seventh centuries BC as, characteristically, she constantly keeps the total Greek tradition in view.

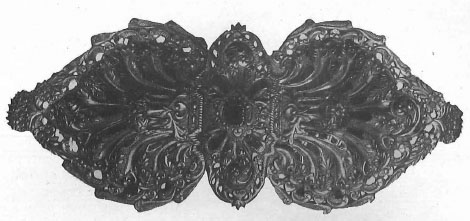

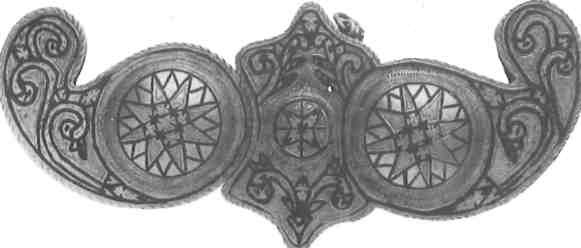

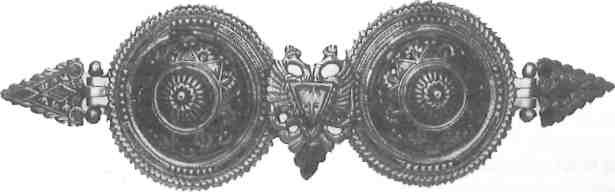

Another very popular ornament, on which a great variety was lavished, is the belt buckle, or porpi. Huge or dainty, they are made of pure and not so pure silver, sometimes of mother-of-pearl , and often engraved with religious symbols, human faces, leaves, flowers and birds. The buckles of Soufii (famous also for its silk) in Thrace are exceptionally lovely as they are composed in three parts, the central one being in the shape of a diadem – hence the name ‘the buckle with the crown’. These buckles usually weighed an oka (a bit more than a kilo). One in the Benaki Museum bears the date 1788.

A special type of buckle, symbolic in character, is that offered by the groom to the bride at the traditional nuptials. It was sent to the fiancee on the Friday or Saturday before the marriage. Often engraved with naivete, with pine seeds or stylized vases of flowers, it was felt that these symbols of fertility were transferred to the woman who wore them. The buckle generally is the symbol of virginity, or its loss.

Therefore, in some areas, newlyweds were pulled into their new house with a belt. Elsewhere, the bride brought a plate covered with a red, silk kerchief and a belt to her mother-in-law. Silver belt buckles from Asia Minor encrusted with pieces of coral, and known as tis Safrabolis from the name of a town , are remarkable for their distinctive beauty.

Often, earrings were so bulky, long and heavy that instead of being attached to the ear, they were hung from a scarf or other headdress. The Byzantine style was a rich source of inspiration for artisans in the creation of earrings like those that hung from either side of the face, called pependoulia. Famous examples are those worn by the Empress Theodora in the San Vitale mosaics.

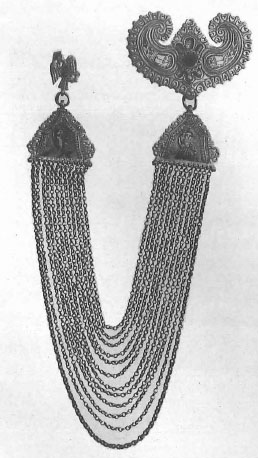

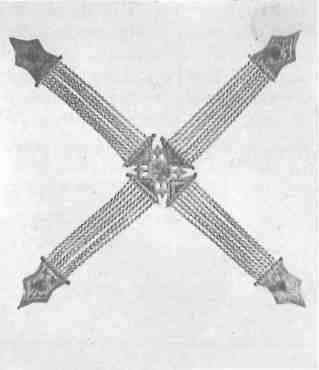

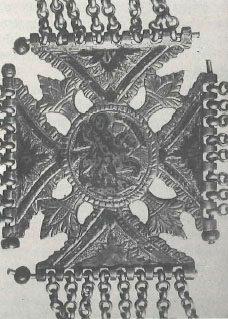

Coming from the Turkish word capraz, anything worn in the shape of an ‘X’ is called tzaprazia . Usually made of silver, they were worn by men and women across the chest. From a central engrav’ed piece, four series of chains extended, each ending in a different decorative element. These tzaprazia were especially popular in communities dependent on stock-raising, so they are mostly decorated with the Byzantine double-headed eagle, Saint George (the patron saint of shepherds), the Virgin Mary and Christ.

No doubt, the most luxurious jewellery was that which accompanied the nuptial costume all over Greece but especially in Attica where the bridal dress was a treasure of embroideries and jewellery. A golden piece was worn on the forehead and other pieces around the neck. A net of gold beads called giordani, covered the upper part of the chest while ten rows of chains, cordoni, hung over the bosom.

Chains of all kinds, made up of real or counterfeit coins , demonstrated social status and wealth . Those that circled the head , with coins affixed to the forehead were very popular. Special chains composed of rhomboid-shaped jewels, interspersed wi.th crosses and known as botonia, were particurlarly common in Crete. The women of Kastellorizo were particularly famous for their rings which they wore in a series on every finger, holding their arms across their chest and clutching their shoulders with their hands to show them all off.

Mrs Korre-Zografou has written a monograph on the rings of Crete which were offered at engagements. Symbolizing the obligation of the woman who received it, and displaying at the same time the groom’s wealth, the ring was bound with a red thread , accompanied by a gold coin and offered with an embroidered kerchief.

Jewellery makers were called kouymtzides and their guild was divided into 25 specialized skills. They had village workshops, but they often travelled in the Balkans and Asia Minor, taking orders or selling their wares at local festivals . If they were lucky, someone – most likely a doting father or an infatuated husband would order a set of jewellery, comprised of many pieces called, as a whole, takimi.

Complimenting costume, jewellery distinguished social position. Different sorts of jewellery were worn by married women and women who were not . In many areas, women over 40 were not supposed to wear jewellery at all. Being a basic commodity of wealth, it was liable to established custom and unwritten law. For example, on Karpathos, on the death of the parents, all the family jewels went to the kanakara, the eldest daughter.

Pieces of jewellery were not only worn as adornments or symbols, but also as amulets. In the manner in which they were made or worn, they were felt to play a role againstthe Evil Eye, as in the case of the little bells attached to the back of the traditional costume of Astypalaia which rang lightly when the wearer walked. So, too, jewellery worn on the forehead between eyebrows and hood consisted of five rows of coins which were sewed on leather. These symbolized the five nails of the Crucifixion and a gold crucifix hung over each row.

Among the techniques of working metals, there was tepousse, where metal was hammered on tar on the reverse side.

Another technique consisted in pouring the molten metal into molds and then trimming it by hand. Filigrana, using very fine metal wires, is a technique known since Hellenistic times and was very popular in Epirus, especially in Ioannina, where many workshops still continue the tradition.

The technique of cutting through metal, producing a result remarkably like lace, is known officially as opus interassile.

Often, artists mixed techniques to give more striking results. One of these was savati, known internationally as niello. This consists in filling the carved cavities of a metallic surface with a mixture of powdered silver and lead. Artisans still keep secret the proportions that they use. When fired, this mixture melts, giving a black outline to designs on silver and, more rarely, on gold. For gilding jewellery, artists usually used 24 carat gold from melted down Venetian ducats.

Although the dangers of perishability for jewellery was great in the past, especially during the Ottoman domination with its bandits and looting and its sudden reversals of fortune and miserable conditions of life, the greatest destruction has taken place recently.

The 1950s may accurately be called the black decade for Greek traditional jewellery. It was especially during these years that the rural Greek people exchanged broadside and wholesale their traditional treasures for plastic and other modern conveniences. They sold their heirlooms by the oka to peddlar antique dealers who travelled up and down, stripping the country of its heritage. Returning to Athens, they sold the lot for what they could get. In this way many of these treasures went to antique shops and found their way into collections, but the rest was melted down.

“This milestone date fixes the boundary which ends traditional jewellery-making,” says Mrs Korre-Zografou ruefully, but cheers up when she speaks of two latter-day gems which brighten her precious world: Stelios, 11, whose painting is already showing his maturity, and Helena, 16, who is becoming seriously interested in Greek traditions.