If you are looking for autumn colors, refreshing streams and a bit of fishing – with some of the most delightful chapels in the country thrown in – think of going to Veria. Lying on the first foothills of western Macedonia, the town looks over the plain to Aliakmon, most Greek of rivers, whose poplar-lined course, particularly in October when leaves drift across it, has often been recorded in films seeking to recapture the nostalgia of a rural past.

Because of its natural richness, it is no wonder that Veria is one of the oldest, continuously settled areas in Greece, dating back some 8000 years. Although the date it was founded and the exact identity of its original inhabitants are unknown, the Macedonians did find it inhabited when they arrived in the area in 1100 BC.

The word ‘Veria’ brings to mind a flow of water from the last two syllables, ‘ri-a re-o’, from the Greek word, meaning ‘flow’. According to Greek mythology, the name derives from the nymph Verroe, the daughter of Okeanos and Thetis. Verroe, who was born in her parents’ ocean palace, is said to have fallen in love with the location on first sight, and given it her name. Other accounts give her a different lineage. One says she was the love child of Adonis and Aphrodite; another, the daughter of Veritas, the founder of the Macedonian race.

Veria was a political, cultural and religious centre of ancient Macedonia, reaching its peak during the Andiyonian dynasty (306-165 BC), which may very well have come from Veria itself. At that time, Veria was rich in agriculture and livestock, renowned for its royal stables and royal hunting grounds, and for its priests in the service of the holy Macedonian river, Aliakmon, as well as Zeus, Apollo, Hercules, Artemis, Ares, Aphrodite, Dionysos.

When the Romans took over, Veria, as well as other Macedonian cities, were declared ‘free’ states, as part of the Roman strategy to divide and rule. This did not prevent the Macedonians, remembering past glories and the times when they ruled and were not ruled, from staging periodic uprisings. The Romans nevertheless seemed to have forgiven the Verians for their trespasses, since they made the city the centre for the Macedonian worship of Roman emperors and gave them the right to mint their own coins.

Veria prospered under the Byzantine Empire. In 904, however, the Saracens, finding the city in chaos after an earthquake, took advantage of the situation and looted the town, kidnapping the women and selling them on Islamic slave markets. This was the beginning of almost 300 years of turmoil, which saw the city pass into the hands of a host of invaders, including the Goths, the Normans, the Slavs, the Bulgarians, the Catalans, the Franks, and the Crusaders. In 1309, however, Veria fell under Byzantine rule again and remained so until it fell to the Ottomans. During this period, there were numerous churches built, many of which stand to this day.

The Turks finally conquered and held Veria in 1436, after a 50-year period of alternated rulers. The first uprising against the Turks came 12 years later, which the Turks avenged harshly with rape, looting and slaughter. From early on in the Ottoman occupation, kleftes made life difficult for the Turkish army by conducting guerrilla raids from Mount Vermion.

In their attempt to stabilize the occupied territories, the Ottomans endeavoured to convert Greeks to the Muslim religion. In Veria, this gave rise to a unique custom, as described by the 17th century Turkish writer Evliyia Tselebi. He informs us that during ‘the days of the red eggs’ (Good Friday to Easter Sunday), the Muslims would put on their battle gear, run wild in the streets screaming out their battle cry “Alah, Alah” and gather up any fine young infidels they could find. They would then dress them up as Muslims, put them on a decorated mount and paraded them around town as converts to the faith. Afterwards, money would be collected from the Muslim residents of the town and the proceeds given to the converts so they would have the means to live well. Understandably, the Greek residents preferred to spend Easter locked up in their homes.

Veria became a Greek city again on 16 October, 1913, when it was liberated by the Greek army. The population, however, remained predominantly Turkish until the population exchange of 1922. The majority of the refugees who came to Veria originated from Asia Minor (which today constitutes the largest ethnic group in Veria) and others came from eastern Thrace and Pontus.

After the population exchange, a brief, peaceful and prosperous period followed, which was interrupted by World War II. The skillful diplomacy of then mayor Kambitoglou saved many Verians from German bullets. However, the treacherous Touliki’ who worked alongside the Germans, were positively ruthless with their fellow countrymen. Following a partisan attack on their headquarters, the Pouliki ran amok in the streets of Veria, killing indiscriminately anyone they found in their path. They had further plans of setting fire to the town and looting it but the mayor persuaded the Germans to call off their dogs and thus saved the city from a major disaster.

As the kleftes had done during the Turkish occupation, the partisans took to Mount Vermion and controlled it throughout the German occupation, conducting many damaging raids from this base. This stronghold was made possible by the support the partisans received from the residents of Veria. Verians are justifiably proud of the role they played in the resistance.

As in ancient times, Veria today is once again thriving economically. Thanks to its ample supply of fresh water and fertile soil, fruit cultivation is flourishing, with peaches and apples leading the way. There is also wheat, clover, cotton, which, along with its canned food industry, has given Veria a yearly surplus over ten billion drachmas in its balance of trade. All this means that there is a lot of money circulating in Veria and all sectors of its economy are doing well. Thus, Veria, unlike other small cities and villages in the country, is not experiencing an exodus of its young people, since there are plenty of opportunities at home.

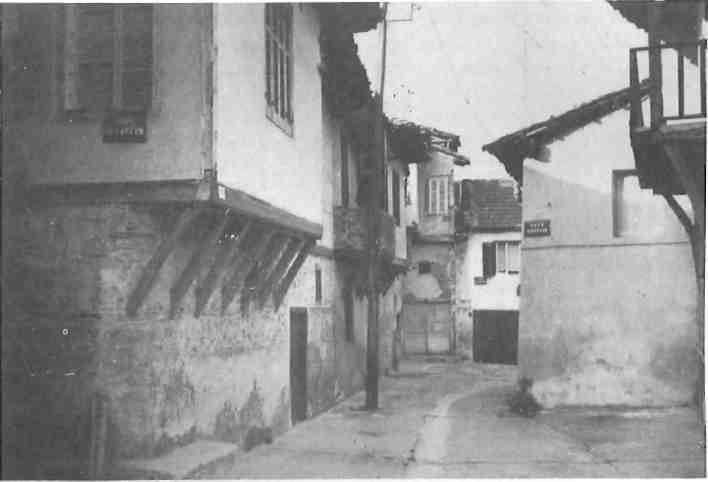

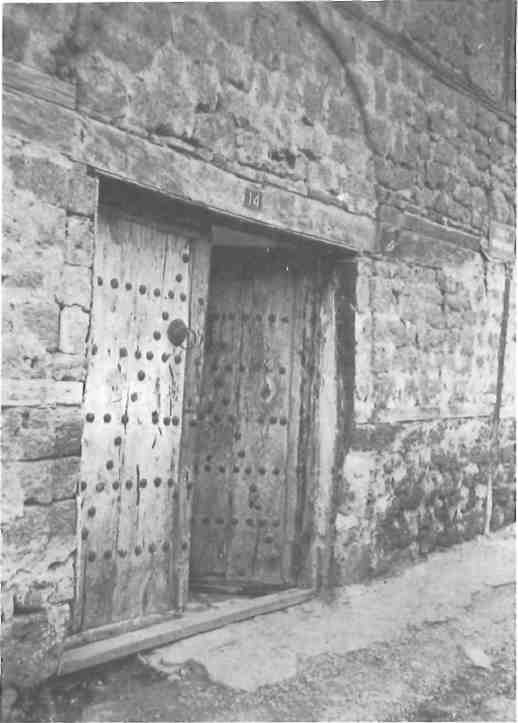

Despite Veria’s expanding economy and consequent construction boom, the city has made efforts to retain its traditional flavor. There are two areas, Kariotissa, near the centre, and Barbouta, along the River Tripotamos, to the right of Orologias Square, which contain the largest concentration of old Turkish and Macedonian housing. The latter are distinguishable from the former by the wooden beams that support the little room jutting out from the main structure. The houses in Barbouta are generally on a grander scale, but they also tend to be in a worse state of repair. Some of the houses in both areas are still occupied (mostly by seniors) and several have been tastefully restored, renovated and expanded, but for the most part, they have been abandoned and have sadly deteriorated into hovels. The city does provide owners of traditional houses with a five-million-drachma grant to repair and restore their structures. Most owners, however, find more economic sense in letting the buildings crumble and building a block of flats on the site.

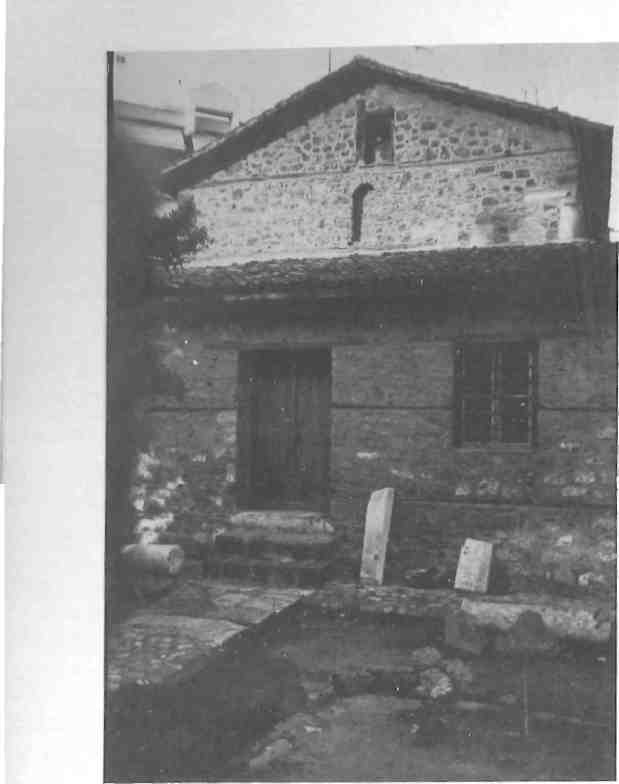

In and around Kariotissa and Barbouta, you can find most of Veria’s Byzantine churches (around 50), as well as the old Turkish baths, a couple of mosques, and the old market sector, with its weird mixture of tiny, old and new as well as new-disguised-as-old shops. If you go on a hunt for the Byzantine churches, you would be hard-pressed to find more than^a dozen without a guide, since most are disguised as houses and are locked up.

One church that is easy to find and definitely worth a visit is the Church of Christ, smack-dab on the main street, Mitropoleos, a little up from and on the same side as the city hall. Built in the early 14th century, the church is in mint condition. Even more remarkable are the excellent exterior wall paintings done in 1315 by the renowned artist from Thessaloniki, Georgios Kalliergis. These paintings bear the stamp of the artist’s individuality, his almost impressionistic disregard for exact reproduction of the human form, and preference for an inward look at the human soul, thus creating a deep sense of balance, peace and harmony in these masterpieces.

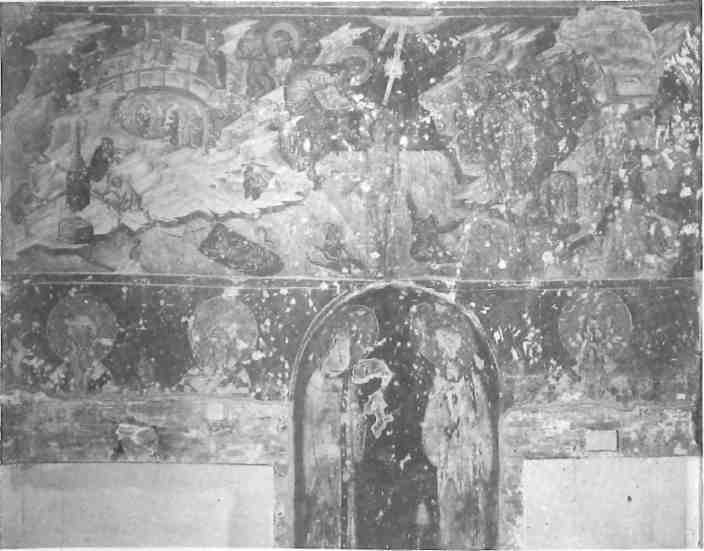

Another fine example of Byzantine art and architecture can be found in the Old Mitropolis at Perikleous Sofou and Kamara, just off Mitropoleos Street. It was built from 1070 to 1080 under the orders of then Veria Bishop Nikitas and, despite the fact that its entire southern sector is in ruins, it is regarded as one of the finest examples of middle Byzantine architecture available in the Balkans. Following the expulsion of the Franks in 1224, the wall paintings inside the Old Mitropolis started decomposing in the early 14th century. Of particular interest are the paintings on the eastern wall depicting the life of John the Baptist.

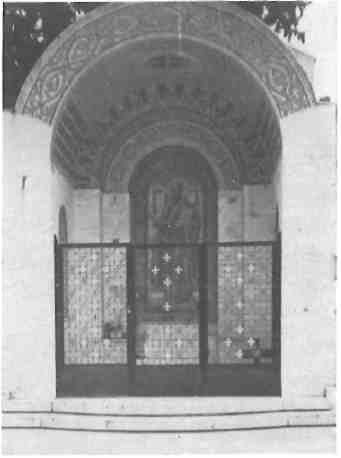

Another must on the religious tour is the pulpit of Saint Paul, which is located in a small park to the left of Orologias Square. Saint Paul visited Veria at least twice in 56 and 57 AD and preached the gospel from this site to the sizeable Jewish community that existed in Veria at that time. Saint Paul won over quite a few pagan Greeks as well and, since then, the site has been sanctified. Do not expect to find a pulpit there, though. It is in fact a shrine built around three white-washed stone steps from where Saint Paul apparently stood and preached.

Given the wealth of archaeological findings in the area, Veria’s Archaeological Museum is not as impressive as one might think. A naked Aphrodite is to be found there, along with a headless Athena, engraved Macedonian columns and tombstones, a superb statue of Olyanos, a Macedonian river god, and other artefacts from ancient Macedonian and Roman times. These are worth looking into but do not expect to be bowled over.

Veria is quite lively in terms of cultural events and entertainment. Theatre and music have found fertile soil in Veria, thanks to avid support by the city’s young people. The young also take a leading role in the traditional ethnic celebrations and dances organized by the city’s Vlach, Pontian and Cretan minorities. At night there are many cafeterias, pubs, discos and tavernas to choose from, along with the traditional stroll up and down the main street. Celebrations and festivals in nearby villages include Anastenaria, in the village of Meliki, from May 21 to 23, where residents dance on hot coals in honor of Saint John, and the Pontian festival at Saint George’s Monastery in Rodohori.

After reading this, you may be ready to pack and move to Veria for good. But hold on, there is trouble in paradise.

Trouble, for some residents at least, has come in the form of an ethnic minority: the gypsies. The gypsies have found a ‘favorable political climate’ in Veria and some residents have complained that the gypsies have become rather cocky, taking over the main square, Orologias, and pursuing some rather aggressive panhandling practices. An increase in thefts has also been blamed on them For outdoors types, there is good fishing in the Aliakmon River and wild boar hunting on Mount Vermion and Mount Seli. In the winter, Seli is northern Greece’s favorite and best equipped ski centre, boasting three ski lifts and two lodges providing about 150 beds.

If you get tired of trekking around historical sites, you can relax at Elia, a parkland area at the south end where the city abruptly begins. Elia is carefully tended (with well-pruned bushes and no litter), and the older folk tend to congregate there with their grandchildren. There are also several large outdoor cafeterias which draw a younger clientele.

From Elia, there is a sheer declivity, which provides this location with a marvelous view of the Macedonian plain below. This striking geological formation seems to suggest that Veria had a Iakeshore, or perhaps even a seashore, which means that the Thermaikos Gulf may have extended as far north as Veria. However, there are wildly differing accounts as to when this was the case.

For archaeological buffs there is, within striking distance of Veria, the most celebrated Greek site excavated in recent years. Late in 1977, Professor Manolis Andronikos and his team from the University of Thessaloniki uncovered two chamber tombs near the village of Vergina, 16 kilometres away from Veria. In doing so, he disclosed what became the greatest archaeological finding concerning ancient Macedonia, which led to literally rewriting history books.

The first chamber he found had been looted but did retain a wall painting of the rape of Persephone, the only complete ancient Greek painting found to date. The second chamber, however, was remarkably intact. Professor Andronikos then announced to the world that he found the tomb of King Philip, father of Alexander the Great, and, logically deducing from this, the site of Aigai, the first Macedonian capital before being transferred to Pella, where Philip was murdered. Professor Andronikos’ theory was highly disputed at first; however, the analysis of the evidence, together with further important findings, seem to have borne out his theory.

When first discovered, Vergina attracted worldwide attention and brought a consequent boom in tourism. However, the ongoing research which closes the most interesting sites to the public, along with the fact that the most impressive findings have filled up the Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum, has resulted in a domestic as well as international waning of interest in Vergina. To renew interest and increase tourism in the area, Veria’s city council has launched a campaign to have a museum built at Vergina, where all the artefacts found on the site and (especially those currently on display in Thessaloniki) would be exhibited.