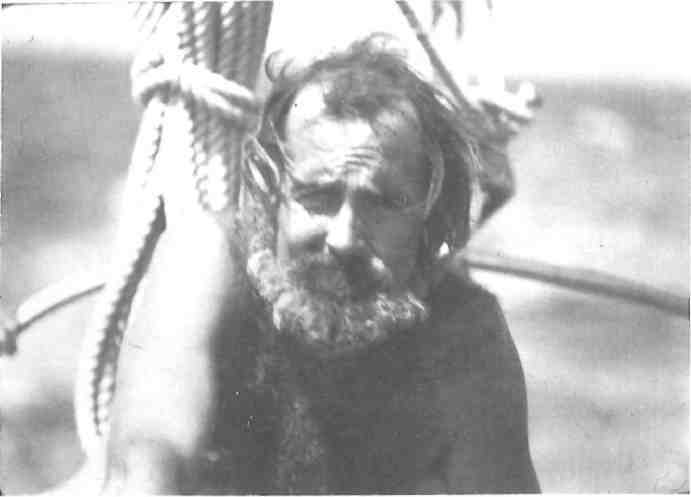

The yellow-green nets had been piled underfoot for years, beneath the teak grillwork of the lazaret. Tom Foyle had begun to take them out and spread them along the stone jetty, where he would sit for hours, with nets held between his toes and teeth, while his hands danced in and out. His teeth made audible clicks as he snipped off loose ends. Except for his ruddy cockney complexion, he resembled centuries of Greeks who had sat around this harbor stretching nets between their feet and teeth.

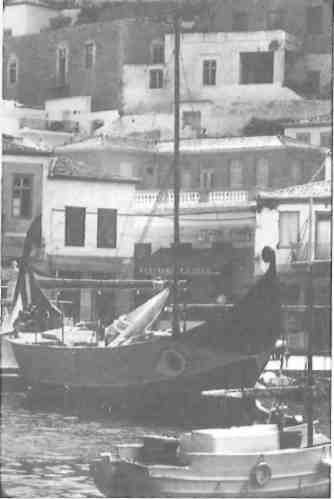

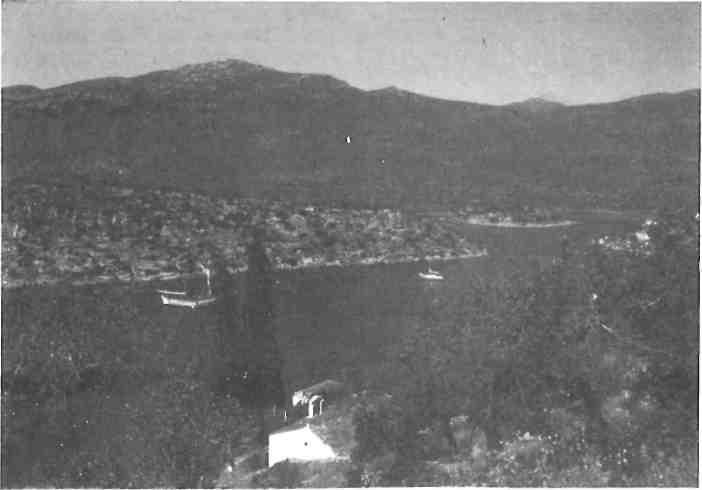

On either side of the harbor, steep cliffs stood where weathered bronze cannons protruded through granite ramparts. Behind the cliffs Hydra rose in the geometric manner of an amphitheatre. The remainder of the island was largely uninhabited and inhospitable save for a few coves.

We were anchored with our stern warped to the jetty. Over the bowsprit the antique filigree of twin marble towers was visible, with bell ropes dangling through the scribed arches to the cathedral roof below. The snug harbor was ringed by walled mansions resting on monolithic buttresses, granite island palaces adorned with marble columns and arcades, with sweeping white marble terraces offering opera-box perspectives of the harbor activities below. And beyond was a panorama of the crisp blue sea and the Peloponnesian mountains.

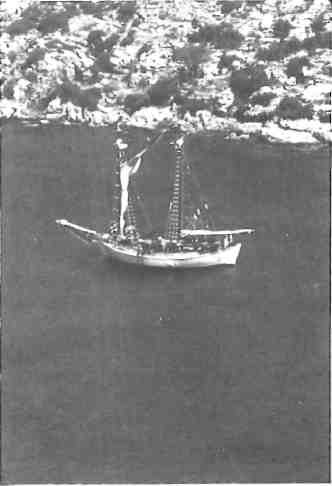

In spite of her Elizabethan name, Stormie Seas was the last traditional schooner built in Greece by Greek hands. In many ways she was linked to the past. Her first owners, Sam Barclay and John Leatham, were legends in Greece during and after the war, and had used her to smuggle agents into postwar Albania on behalf of British intelligence intent on disrupting the solidifying communist regime. She was the epitome of the Greek schooner and her shipwright’s craft. And she was linked with the past in another way. My mates had discovered the world’s oldest known shipwreck with her, not long before, and not far away, a wreck that occurred as long before the time of Alexander the Great as he was before our time.

I watched Tom Foyle sit day after day shrouded in nets and their endless patterns of diamond knot. There would be a few weeks before my·first charter, and we had planned to go to the remote side of the island and spend some quiet days spreading varnish and mending the necessary rigging. And we would try the nets. The day after Tom had finished them, at last, I knew it was time to go.

The flying jib rose first, then the gaffed foresail creaked up the mast on rings of large wooden beads. I cut the diesel when the main began to jerk upwards, Tom doing the work of several larger men with the weight of his years. We heeled slowly and she put a shoulder to the waves. What a sensation of freedom!

A steady wind blew pine scent offshore to us as we rode down the steep, plunging coastline. The brisk blue waves trailed fine white lace. We were silent, lulled by the shush of each wave that sped past the hull, muted by the audacious geometry and proportion of the dull gray landscape. Entire mountains, splashed faintly with scrub and broom, clusters of sage and thyme, and cordons of asphodel, appeared to fall into the sea. The knife-like ridges swept miles down to the sea, from mauve, hazy peaks.

Suddenly, there was a loud shout! Tom Foyle stood frozen, pointing off the stern. I looked. After several seconds, I saw it too, a sleek and dreamy turtle was gliding just under the surface of the sea, with a wondrous absence of effort for such abundant speed. His flippers were extended but motionless, as he glided regally and smoothly through the transparent waves. Then, he roiled his head, languidly, as it burst through the rippling surface, the heavy hide of his neck moving as his horny nostrils sucked air.

With an imperious nonchalance, a large brown eye gazed upon us. The eye, poised above the dancing waves, looked on with a seeming mixture of casual curiosity and disdain. Then he had had enough: he abruptly vanished in a display of swift and savage power.

When the water cleared, we gave chase, stiffening the canvas and easing onto his heading at an increased speed. The glistening brown and ivory mirage shot through the water on supple leathery wings. We followed for nearly a mile before he darted off to the west. I suspected he was toying with us.

It was late afternoon when we anchored at Aghios Nikolaos. There was not the slightest sign of habitation. Off to one side of the bay there sat a small island no more than 100 meters long with little vegetation but thyme and thistle. We took the dinghy out to it, intending to drop the net between the islet and the shore. There, squeezed between the two, the current would be compressed and accelerated This, we hoped, would fill our net with fish.

Tom rigged anchors at one end fixing our good grapnel and, at the other, a stone slung in a web of line like a cheese. He attached a buoy and we were ready.

Even the slight current made rowing the net across the narrow channel an effort. Straining against the oars, I could feel the floats resist and the lead weights quiver in the water. The dinghy barely moved as I fought to remove the sag which the current had pushed into the net. After much heaving, I had it fairly straight and taut; we laid the last half in near dark. The evening star had begun to sparkle when we anchored the bitter end with a splash. We had spanned the channel with it.

Back aboard the boat, I ran a hurricane lantern above the bowsprit to serve as an anchor light. The breeze had vanished by then, and in the warm evening we supped on bread and goat cheese, black pulpy olives and wine. We passed the night under a wide sky of gently-rocking stars.

In the Aegean, fishermen rise early to tend their nets, before strangers do it for them. Poachers do not sleep. Neither of us was accustomed to awakening at dawn, so when we did, the thought of rowing the dinghy a mile back to the fish-heavy net put us off. We decided to do it the easy way and move the schooner out into the channel. We fired up the engine and took turns grinding in the anchor chain.

The marker buoy bobbed where we had left it. I throttled the diesel down to match the speed of the current running in the channel and lashed the tiller in place. Then I clambered into the dinghy and rowed out to the net and began hauling it in. There were few fish in it, and all had been partially devoured by some unknown marauder.

The net did not feel right. With a quarter of it remaining out, I felt a snag. It would not budge. I rowed directly over the suspected snag and heaved as much as I could without swamping the dinghy. It would not give the least bit. Tom cupped his hands as if shouting at me.

‘The current is setting us off…let me make it fast here, and we can drive the damned thing off the snag!”

”But we’ll ruin your net, Tom…”

“I don’t care.”

“Nonsense, Tom, you’ve got hours caught up in that net. Toss me my diving gear and I’ll go down and swim it free.”

Tom tossed the gear down and I pulled the dinghy back out to the snag and cleared my mask. When I was ready, I sat on the dinghy’s stern and fell backward into the water. I blew my snorkel clear and stared down at the bottom.

The chart indicated the bottom of the channel to, average five fathoms, from side to side. I looked down; it appeared bottomless, and the water had an unusual chill to it. I shook off the uncommon cold as I realized it must originate from offshore currents welling up. I traced the net from where it rose out of the blue gloom, toward the small island.

Then, suddenly, I saw it. The supposedly unobstructed channel had a reef running a third of the way across! A wicked spine of rock jutted to within one metre beneath the surface. All of it was wrapped tightly in the net. How close we had come with the schooner!

I told Tom to play out the net, as it was holding us to the reef. “What bloody reef?”he shouted back before I dove.

Infinite colonies of red, yellow, and purple sea urchins dotted the reef, with spines as long as sail needles sticking through the net in a hundred spots. Their abnormal size suggested dynamite fishing. The thick rubber of my flippers would protect me if I was cautious, and I intended to be. I planted my feet against the reef and began yanking a few feet of the net off at a time. One slip and I would have dozens of porcelain needles embedded in my skin. I fed Tom what I managed to free. He hauled it snaking cross-current and onto the deck of the schooner. He had a decidedly annoyed look on his face.

While swimming a cleared section of the net away from the reef, I saw something I had never seen before. I thought my vision might be deceiving me. At first, it was beyond my comprehension.

The channel floor, in the shadow of the reef, was covered with objects the size of cannonballs, which I first thought they might be. But they were too irregular in size, though very round, and encrusted with pale blues and grays that blended with the coloration of the bottom. Looking more closely, I saw that they formed an almost perfect cone. It shimmered in marine distortion one instant, then revealed its hard form the next. The significance was not immediate.

And then it hit me! I was above an ancient shipwreck! They were ballast stones, ancient stones thrown overboard with such haste they had formed a cone nearly five metres high. Its perfection suggested that the vessel had ceased moving as the ballast was dumped, all in one spot. The ship must have rested on the reef. I had learned that whenever you endangered a boat in these waters and escaped, you could always find evidence of some who had not. This was a monument to such a disaster, a monument likely built by the doomed.

I hurried with the remaining part of the net. Just having the schooner riding above, so close to the reef, made me nervous. I had a quick look for signs of the hulk, maybe a suggestion of a skeletal shape on the floor.

Then it happened!

All 50 tons of the schooner had begun to pull on the net, and the slack was vanishing. Before I knew it, the net was bearing down on me, and I was being carried through the water. The boat must be veering across the current and the net must be fouled on deck! If Tom Foyle would only notice what was happening!

I did not have much time, or air in my lungs, as I was pushed closer to the reef. I had to gamble. I kicked and thrashed downward, snapping, crushing shellfish on the surface of the reef as it pulled tighter. Shell and debris clouded the water and filtered down to where I stood, upside down, with my feet on the ledge of reef over my head. I did not have any time. I kicked down hard with all my might, down, down.

I seemed to be dragging the net with me, and I felt its cords cutting into me. The lead weights vibrated as I dove, to my astonishment, and I felt the last of the oxygen being squeezed out of my blood. I would have to do without it. Then, I felt the net slip free! I kicked downward again as a precaution before floating, at last toward the surface, with aching lungs.

I rested for several minutes after Tom gave a shout. Then I swam, weakly, toward the dinghy. I looked down at the luminous mound for a parting glance. It was a web of shape and color, and it reminded me of a painting by Pollack. And then I remembered the title: Full Fathom Five from the lines “full fathom five thy father lies, ivory were his ribs, coral were his eyes…” An Elizabethan adaptation from lines by Sappho. It was the sequence of memory that startled me.

I swam out to the schooner pulling the dinghy. Tom had it secured as I climbed limply aboard. I was wrung out. As I dropped my gear on the deck, the diesel began to throb, and then slowly revved up. We began to move out of the channel, to the sea. I heard the filament twang and snap, followed by the float line’s parting, and whipping viciously across the water separating us from the reef. We were free.

Foyle pushed the throttle up some more. We had lost over 30 metres of net. What remained was again snarled and tattered. Later, Tom Foyle would coil it and place it back. It took up a lot of room in the lazaret, but for the time being that would be fine. Just fine.