Just the name Mount Olympus conjures up images of myth, majesty and mystery. So closely has it been associated with the home of the ancient Gods, that many believe it vanished centuries ago into legend along with its divine inhabitants, and are surprised to find it still soaring out of Greek topography.

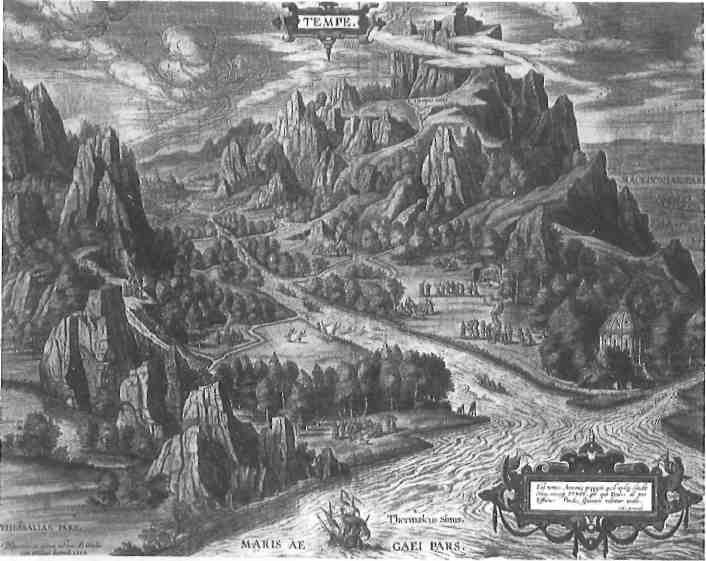

There are many mountains in Greece still called Olympus, and even more in Asia Minor. It seems to have been a pre-Greek word meaning ‘mountain’. But the Olympus in question is the highest mountain in the ancient Greek world and is therefore the most suitable home for the mightiest of its Gods: the great Cloud Gatherer, the Bringer of Rain, the Hurler of Thunderbolts. The idea that Zeus ruled over a family of Gods on this particular mountain, however, was imposed by Homer on the minds of later ages, according to Martin Nilsson, who is the ultimate authority on this earth-shaking subject.

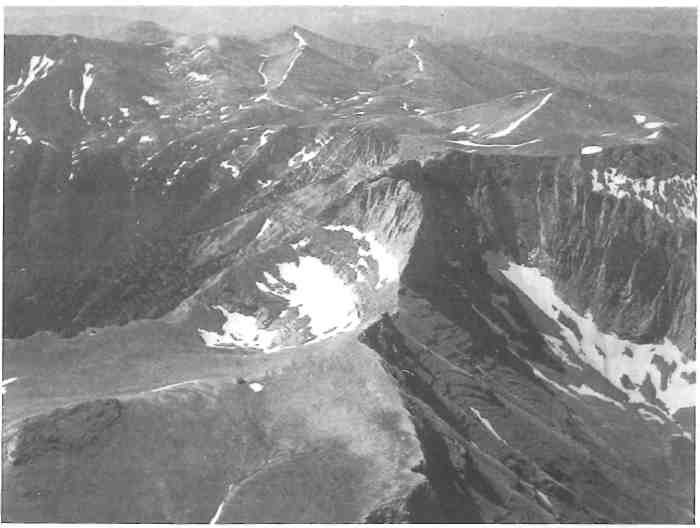

Mount Olympus, vied with Delphi as the centre of the earth, according to ancient Greeks, but wherever it lies in relation to today’s universe, it is located between Thessaly and Macedonia. It is snow-capped for nine months of the year, bare of trees above 2200 metres, mostly forested with conifers below this height. Recent excavations at Dion, located at its foot, attest to the great religious significance of this ‘holy mountain’ in pagan days.

According to a Christian legend, the Gods abandoned Mount Olympus en masse in 4 BC, and it was never inhabited again until it became a favorite resort of Klephts, who were god-fearing, Greek Orthodox bandits. It became a traditional stronghold of the resistance throughout the 400 years of Ottoman occupation, the German occupation during World War II, and the Civil War which followed.

Besides its great height, Olympus is renowned for its flora, which includes many rare endemic plants (Campanula oreadum or bellflower, Jankea heidreichii, Potentilla deorum, etc). There used to be an abundance of wildlife on the mountain, but hunting and poaching have exterminated many species. Among those that still exist but are rare, is a herd of wild mountain goats, a few Golden eagles, and some species of smaller birds and animals. Olympus is now a national reserve with its endemic wildlife and flora strictly protected.

The peaks of Olympus are known to have been first conquered (at least by mortals) in 1913. The conquerors were two Swiss climbers, Boissonas and Baud-Bovy, along with Christos Kakkalos, a native of Litohoro, which lies at the foot of the mountain to the east. Olympus, nonetheless, is a very ‘democratic’ massif in that it requires no special mountaineering skills or athletic prowess to scale. Anyone who is reasonably fit and has the desire to complete the trek to the summit should be able to do so. Pregnant women in high heels and old-age pensioners have been known to climb two or more peaks in a single day.

Similarly, no special equipment is required. Hiking boots will ease the strain on the ankles but a good pair of trainers are adequate for the task. On the other hand, one should not be fooled into thinking that the climb is a casual stroll. As with all mountains, ascent should be approached with a reasonable amount of caution.

Mountaineering accidents, though not common, have occurred on Olympus. On 26 March, 1988, an avalanche at a height of 2300 metres swept away 55 climbers, dragging them 400 metres downhill. Nine of them were seriously injured but there were no fatalities. In December, 1976, however, an avalanche killed two climbers and six were

dragged to their deaths in 1979. Nevertheless, most of the accidents that occur during the summer months, according to members of the Litohoro Mountain Rescue Squad, are caused by lack of common sense. For example, a German climber was badly mauled earlier this year when his backpack became too heavy with rocks he was collecting, causing him to lose his balance and fall 100 metres down the side of the mountain. However, if one avoids such foolishness, there is nothing to fear.

To visit Olympus, it is necessary to get to Litohoro. If driving, one reaches Litohoro a few kilometres off the national motorway between Athens and Thessaloniki, near Katerini. If traveling by bus from Athens or Thessaloniki, depart from the bus station which serves ‘Nomos Pierias’, the neighboring area.

Once in Litohoro, one can begin climbing or drive on to Priona, where the mountain road ends. If one chooses the former, the walk is very scenic and takes roughly five hours to reach Priona. Be sure to stop at the monastery of Agios Dionysos, which dates from the early 16th century. It is located in the ravine through which the Enippeas River flows. There is a riot of wild flowers along with a thick cover of deciduous trees whose leaves provide a stunning array of colors during the autumn months.

If going on to Priona, avoid taking a taxi because the driver is likely to over-charge. Hitchhiking is fairly easy, provided one starts out early in the day (before 1 pm).

Besides suitable foot gear, one should bring along a canteen of water (one quart, at least), as well as a hat and sunscreen lotion. Water is vital because there is none to be found between Priona and the refuge. A hat and sunscreen are imperative because at higher altitudes, beyond the timber-line, there is no shelter from the sun. The best month to climb Olympus is September, when it is pleasantly warm on the lower slopes and refreshingly crisp higher up.

The trek between Priona and the refuge will take anywhere from two to three hours, depending on one’s pace and rest periods. The path is clearly marked and there should be no difficulty following it. Roughly 45 minutes from Priona, there is a particularly scenic area called Ares’ Walk because of the pervasive redness of the landscape. Here, level ground is flanked by deciduous trees which leave a thick orange-red layer of leaves on the forest floor, and the wild display of color upon entering this area is astounding. Ten minutes before the refuge is reached, there is a snowfield roughly 10 to 20 metres wide, depending on the time of year. The snow is firmly packed and never melts altogether, despite the 85-degree summer heat.

At the refuge (Spilios Agapitos, or Refuge A), you will be greeted by Kostas Zolotas, a personable, rugged mountain man of indeterminable age, and his two large friendly Alsatians. At the refuge, the day’s climb ends, so one can relax, eat, get to know fellow climbers (there is always an international mix) and taste the refuge’s renowned tsipouro. The refuge has room for 90 guests, and provides food, drink and beds. It also has a telephone. A shower is available for those who can brave the ice-cold mountain water. Finding a vacancy usually poses no problem, though a call can be made to confirm (tel 0352-81800). Accommodation is cheap and simple (bunk beds). Except for meat dishes, food is inexpensive, considering that it has to be carted.up by pack animals. (You will probably encounter a small caravan of donkeys on your way to the refuge.)

Mr Zolotas runs a tight ship at Spilios Agapitos, which is spotless and efficient. Lights go out at 10 pm sharp, by which time one should be pleasantly tired. Besides, an early start (6am-8am) is mandatory if the ascent to the summit and descent to Litohoro are to be made on the same day.

After a breakfast of bread, jam and mountain tea, the final assault on the summit begins. From the refuge on, the nature of the climb changes. Trees become fewer and, after a quarter of an hour, the timberline ends altogether. There is a lot of loose rock, and the route, although marked by red paint, is more difficult to follow than the previous one.

A climb of less than two hours from the refuge brings one to Skala (2911 metres), a natural resting spot.. From this altitude and vantage, the scenery takes on a surrealistic quality in the thin mountain air. Beyond this peak, the abyss called Kazania (cauldrons) provides a sheer drop of 450 metres around which the peaks Stefani, Mytikas, Skala and Skolio form a semicircle. From Skala one can climb on to all these peaks, but the highest and most popular is Mytikas (2917 metres).

The ascent from Skala to Mytikas begins with a sudden decline followed by a steep incline. One may initially be put off, but it is not as difficult as it looks. To put the climb into perspective, it should be pointed out that it is not necessary to hang over any precipices by one’s fingernails, but both hands and feet will have to be used on a few occasions. Once at the peak, one can sign one’s name in a book which is kept there, have a picture taken beside the Greek flag, and generally feel satisfied with oneself. The descent from the summit to Priona is roughly five hours and another three and a half to Litohoro.

Another, longer route for the more adventurous begins at Diastavrosi (crossroads) on the way from Litohoro to Priona. Within six hours, two refuges can be reached. The first, Refuge B, is open only if previous arrangements for the keys have been made with the Thessaioniki Mountaineering Club. The second, Refuge C, is open to all during the summer months. Both are located on the lovely Plateau of the Muses, the legendary birthplace of the ‘Heavenly Nine’. From these refuges, one can proceed to Stefani and Mytikas.

Mount Olympus is neither the highest nor the most challenging of mountains, but among non-mountaineer mountains it ranks high. The landscape is awe-inspiring, the mountain air intoxicating. On the human side, there is a universal sense of camaraderie and goodwill amongst the climbers bonded by a common purpose. And, of course, on the divine side, there is a sense of reverence in following the footprints of the Gods, for the Great Mountain still lives where Homer first put it: in the minds of men.