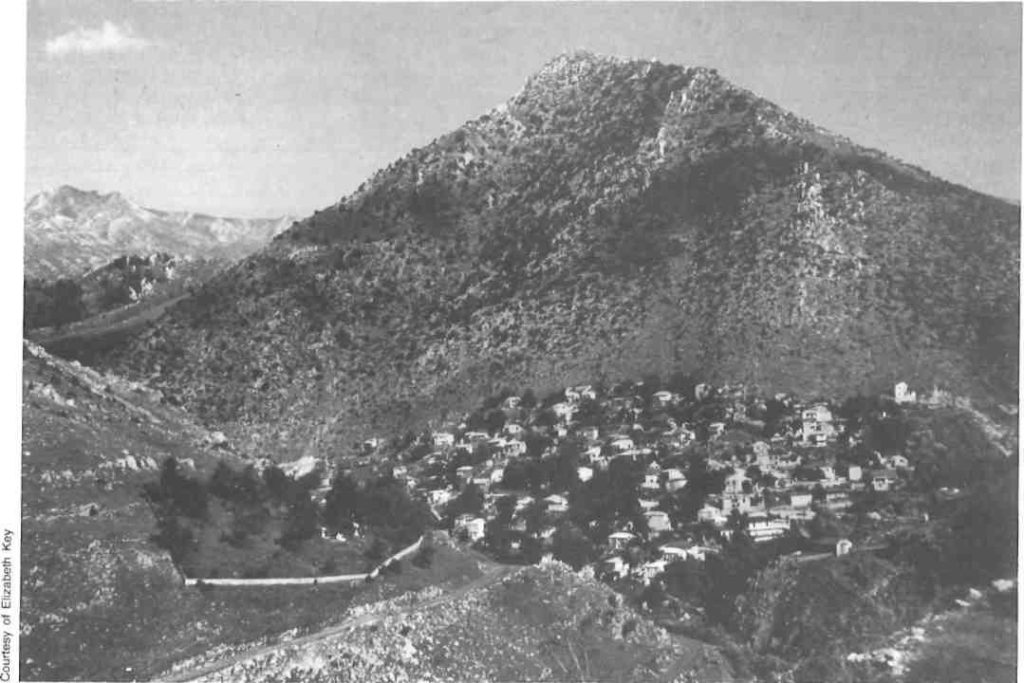

As the summer sun sets, the old men of Krania start up yet another game of backgammon. Today this Greek mountain village is a refuge for townspeople escaping the heat of the Thessalian plain. Some 40 years ago it was the scene of less innocent happenings when local andartes, resistance fighters, took 85 German soldiers prisoner and held them in the Doliana monastery near the village. Before their execution, the soldiers hid their uniform buttons and wedding rings behind the icons of the monastery church. Finding these later, their compatriots took revenge by razing the monastery and bombarding the village, Krania lies midway between Pyli near Trikala and Metsovo, the two villages which marked the beginning and end of our 80-kilometre trek in the central Pindus mountains. We chose this area for its comfortable distance from tourist-soaked Delphi and Mount Parnassus where the Pindus begins, and the popular Vikos Gorge near the Albanian frontier.

To the east the mountains meet the Thessalian plain in an abrupt rock wall, to the west they descend more gradually into Epirus. The landscape of the Pindus has an air of rugged self-sufficiency, and its human history reflects this quality. Even today when few Greeks still make their home in the mountains, the life that persists in the Pindus villages is simple but hearty.

Metsovo, where we completed our hike but which may also be a good starting point for all walks in the Pindus was the only place we stopped at that could be called ‘touristy’. It is spread on a steep slope near Katara, the highest pass in Greece traversable by car, connecting Ioannina across the peaks to the Thessalian plain. With a year-round population of approximately 2000 people, Metsovo is by far the largest of the villages in the central Pindus. In its streets people speak Vlach, a language related to Romanian. On Sundays the women dress for church in traditional costumes and the older men, as in every village on our walk except Pyli, carry the Vlach shepherd’s staff, today more a symbol than a tool of the trade. According to one theory, the Vlachs, originally from what is now Romania, became a settled, Latin-speaking people in the Ror man province of Dacia. With the Goth invasions of the third and fourth centuries AD, these people were gradually pushed southward, some finally taking refuge in the Pindus mountains, where they became settled again, and founded most of the villages in the central Pindus. In the 18th century the Greek monk and noted educator, Kosmas Aitolos, visited these Vlach villages during his travels all through Greece, chastising them for their barbaric speech and setting up schools in which only Greek was taught. In every village square, one still finds the plane tree under which the holy man worked his spell on the shepherds. Today’s bilingual Vlachs consider themselves Greek, but still express their Vlach identity in local traditions.

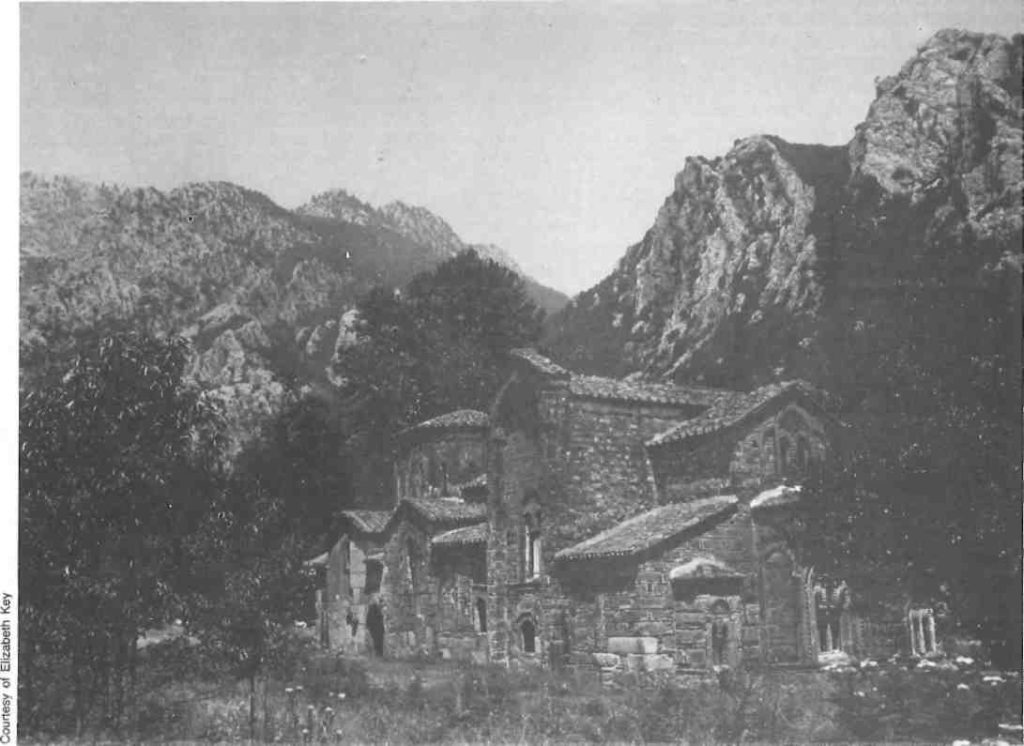

Besides the Vlachs, little is known of the mountains’ inhabitants or history. Greeks themselves felt more comfortable settled on the plain or near the sea. The oldest monument which we encountered on our walk, the Porta Panayia church at Pyli, was built in 1283 by the illegitimate son of a Despot of Epirus who himself married a Vlach. Today, it is the final spiritual consolation for the traveller soon to be caught up in the mountains’ grip. The intricate brickwork rises up in a civilized flourish against the rugged backdrop which closes in around the church. Pyli owes its name “the gate” to its position at the base of the mountains where they open onto the Thessalian plain. In the 16th century, Vissarion, archbishop of Larissa, expressed once more the rivalry between the civilized and the wild, by spanning the river just upstream from the church with an elegant stone bridge, and by positioning a monastery half-way up one of the towering mountainsides above the pass. This monastery, Dousiko, is inhabited today by a group of enthusiastic monks esteemed for their strictness. Entrance to women is forbidden.

The tension between Man and Nature finds equilibrium in the end. In the winter, the snows despatch the villagers to the plain. But in the summertime the scales tip toward civilization as the abandoned villages come back to life. After a day’s walk, we found that one of the most appreciated signs of Man’s return was a local animal roasting on a spit. Near Vissarion’s bridge at Pyli is a taverna that combines a stunning view of the mountain wall with the best kontosouvli that we have eaten, and a fine roast goat as well. Since potatoes, onions, tomatoes and bell peppers were the only vegetables that we encountered in the mountains, meat, its source and preparation, provided the main interest at the table. The village of Neraidohori offered a delicious veal chop, while Krania served up some less-than-tasty ewe which even the fantastic view could not improve.

On the first day’s walk from Pyli up to Elati, the plain’s stifling humidity gave way to fresh air. After Elati, a village which boasts several small hunting lodges, a dirt path leads to Neraidohori passed fir forests and open meadows with strawberries, sweet-smelling broom, and over-sized purple thistles. Neraidohori comes into view at the end of a deep green gorge with sides of convulsed rock. Between Pyrra, down the road from Neraidohori, and Krania is a ridge of 2000 metres. Soon after beginning the climb, we met up with the notorious Greek sheep dogs, kept near starvation to improve their performance. After an unheroic escape, we crossed the tree-line above which only local hunters usually climb and, until recently, a lone shepherd on a mule, carrying milk to the cheese-maker on the other side. Today, cheese is manufactured on both sides of the ridge, so only the hunters know the path. Their number, however, is growing during the autumn season, and now winter sports, including skiing, are being developed in this area. The climb is abrupt and exposed to the sun, but worth the effort since the view from the ridge is spectacular – endless, bare-boned peaks, covered in the snowless months by a thin growth of plant-life suited to summer pasture.

The descent over barren rock leads down to the river valley and a cluster of huts called Kalyvia which possesses surely the sweetest spring of the central Pindus. We took cover there for half an hour during the regular afternoon shower, before carrying on to Krania a bit further up the valley, where the view of the mountains’ silhouettes is sublime.

In these mountain villages, such as Krania, activity centers around the magazi which serves as taverna, cafe, general store and, except in Neraidohori where there is no accommodation, simple guest house. But a room is not a necessity since the absence of mosquitoes and the abundance of grassy clearings and ice-cold springs make sleeping out-of-doors, even without a tent, preferable. Typically, in the mountain villages the houses fan out from the magazi with a generous sense of space, though in recent years many of the gaps have been filled, sometimes with little care for aesthetics. The houses and churches of many central Pindus villages, not only of Krania, were destroyed during the German occupation. Of the houses that survive, Anthousa, a tiny village nestled along a tributary leading off from the main Acheloos valley, has a fine example from the first half of the 19th century. This large stone house, roofed in slate, sits beside the village’s best spring and a large cherry tree. Over the simple lower storey, wooden balconies stretch out from the second and third floors. A heavy wooden door protects the entrance which leads to the large kitchen on the ground floor. Upstairs, in typical Ottoman style, is the family sleeping room, first, and then, on the top floor, the house’s most comfortable room, reserved for entertainment, with a fire-place’ and low sofas covered in richly-woven textiles lining the walls.

The oldest churches date from the 18th century, when most of the Vlach villages were founded. They are large and barn-like, with slate-roofed porches running along the whitewashed exterior. Inside, the coffered, wood paneled ceilings are often delicately painted. But the most distinctive feature of these churches is the elaborately carved and often gilded iconostasis which spans the breadth of the church. Wild beasts and gargoyle-like faces animate its panels overgrown with lavish foliage, and terrible dragons flank the royal doors. The overall impression is enough to distract the viewer from the icons it displays. The iconostasis in the church at Katafyto between Krania and Anthousa stands out for its playful figures and bold primary colors which explode with life. Unfortunately, thieves have all too often been at work, and countless icons and even liturgical furniture have found their way onto the flourishing market for post-Byzantine treasures.

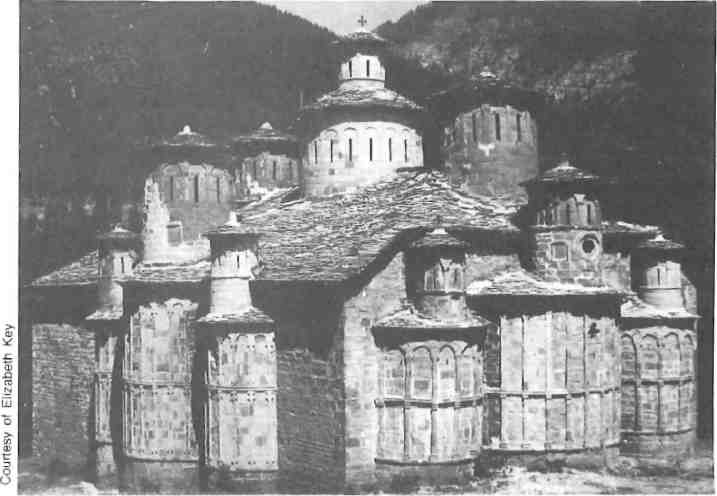

Not far from the sparse remains of the Krania monastery is the Doliana church. Although the interior was burnt, the structure survived the German assault, except the narthex and central dome. The villagers have laudably restored Doliana to its former glory and peculiarity. At first glance, it might be taken for a Byzantine spaceship. Even after longer observation this twelve-domed building adorned with impish reliefs and metal crosses with tiny tinkling bells remains, to say the least, an oddity of 19th-century architecture.

The value of Krania eventually meets the wider valley where the higher Acheloos river is fed by innumerable springs trickling down from the slopes. Here its clear waters never reach much higher than the knee. At the head of the valley, enclosed by rock, lies Haliki, where we were told that bears are still sighted. The ascent to the ridge which separates Haliki from Metsovo is not as dramatic as that between Pyrra and Krania, but the deciduous forests on its northern slope afford a striking change from the dark firs of before.

Metsovo, also called Prosilio, “facing the sun”, rests on the northern slope of a deep gorge opposite, naturally enough, Anilio, “away from the sun’. Arriving at Metsovo from the Anilio side means a last effort to climb up to Metsovo along an old cobbled mule path.

At the finish of our trek we were rewarded with a glass of ouzo in the traditional wooden house of a Metsovo widow, twenty times a god-mother, who recounted for us still more tales of the German occupation, while our eyes were focused on a last, fine view of the mountains of the central Pindus which we had crossed.