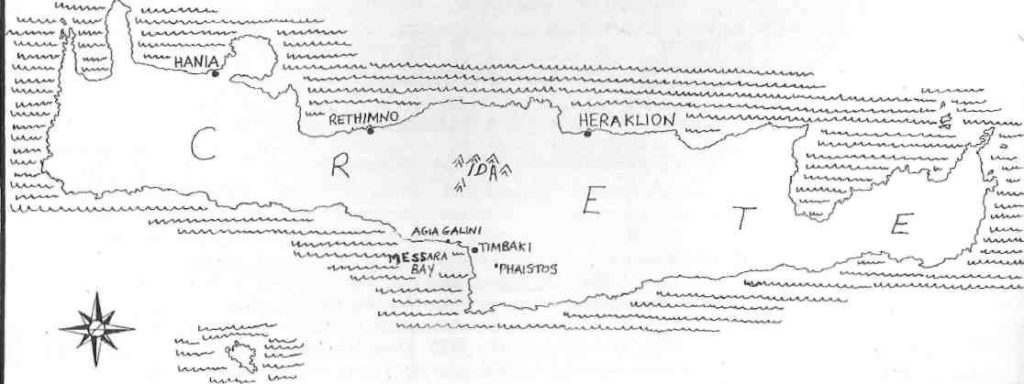

One might forgive the foreign visitor for believing that the small, dusty town of Timbaki in Crete is reminiscent of a Third World backwater on some God-forsaken land. It lies 65 kilometres southwest of the island’s capital, Heraklion, with its 4000 inhabitants concentrated in a jumble of houses nestling amongst the olive groves and greenhouses of the Messara Plain. The area is reputed to be one of the most fertile in Crete and enjoys one of the mildest winter temperatures in southern Europe. The snow-covered peaks of Mount Ida soar to the north, while the shimmering silky waters of the Messara Bay, deep like a bottomless palette of blue paint stirred by a crazy artist to reflect its changing moods, spread to the south. The bus trundles slowly into town behind a convoy of ramshackle, open-backed trucks which are an integral part of the rugged landscape, past the dilapidated shops, coffee houses and ill-lit tavern as, where indolent men in high boots and traditional headscarfs recline. Here the visitor immediately samples a slice of Cretan life.

Timbaki is no tourist attraction; it is a living experience. In fact, there is only one hotel in town, the San Georgio, and a smattering of ‘rooms to let! Its nearest resort is Aghia Galini, some 12 kilometres away, although the town beach of Kokkinos Pirgos, within walking distance, provides a convenient distraction with its handful of bars, tavernas and hotels. In the summer months, locals might drive to Aghia Galini, a pretty fishing village where its seasonal influx of visitors brings life and gaiety, not to mention income, to a muddled economy.

Throughout the year, however, Timbaki is the stage for a cast of foreign oddballs drawn mainly from northern Europe and for whom the attraction lies mostly in the anonymity the town has to offer. Some arrive as tourists and decide to stay for reasons beyond their own comprehension. Others are bent on living a rustic lifestyle and openly sleep on the squalid beaches of Kokkinos Pirgos, venturing to Timbaki for supplies of casual work. And there are those who are simply running away from a world they left behind, subconsciously hoping that life, as simple as it may appear, may offer less complications than that at home.

The main industry is greenhouse farming. Beyond the hotchpotch of shops in the main street, the countryside is littered with polythene-covered greenhouses. Functional, rough-shod constructions, they are nevertheless a scar on a beautiful and lush environment. But then, it is argued, Timbaki is a functional town, a working town, and therefore not geared to the whims of the passing tourist. The Cretans claim, with some justification, that their island is the breadbasket of Greece and that Timbaki is a mere contributor, supplying its bulk of tomatoes and cucumbers to the mainland and exporting to Europe too. “It is essentially a farming community,1′ says Janet Stefanakis, an Australian married to a local greenhouse farmer, “but there are some people in this town who welcome the visitor, if only to see and sample our lifestyle.”

Like many small towns in a country whose main income is tourism, Timbaki is no exception to the cultural change which accompanies it. Its thriving greenhouse industry has brought about an increased prosperity, but the cultural change has been too sudden for its inhabitants to accept. Twenty years ago there were four motor vehicles in Timbaki, the roads were untarmaced, housing was poor, and sanitation and sewage were left to Mother Nature. Most families sent their children to the larger towns for schooling or completed a basic education at the local school. Today, with better communications and a much improved standard of living brought about by tourism in the country as a whole, cars and consumer goods are commonplace. Watching television and video films, evenings at one of the town’s three discotheques, and playing football appear to be the main pastimes of its youth. And, while shops display a staggering amount of consumer goods, civic amenities are depressingly few.

There is, for instance, no hospital, library or recreation centre. Minor ailments can be dealt with locally, but those requiring a specialist, emergency treatment or hospitalization are referred to Heraklion or Athens. The town’s only cinema offers a nightly selection of Kung Fu-style films, war movies and a special Wednesday ‘porn night’. Power cuts are common, street lighting is inadequate, side streets are rough, tracks are full of potholes, and the main road resembles a fast-flowing muddy river when the winter rains descend. Domestic rubbish and discarded containers of dangerous chemical fertilisers are dumped along the bank of its river, the Geropotamos, slowly adding to its pollution.

The Timbaki Wives Group, an organization recently set up by Janet Stefanakis for foreign wives, aims to bring these grievances to the notice of the authorities. The laissez-faire attitude of the Greeks is a quality which foreign visitors find particularly endearing, but living and working in the town is a different matter. As a foreign wife, Janet has had to adapt to the Cretan lifestyle, which she does with unfailing vigour and enthusiasm. “But,” she protests, “I’ve been living here for eight years and I still can’t speak Greek properly. I’m trying to organize Greek lessons for the girls and involve not only them but the local Greek women in some form of community activity.” These are the views shared by the foreign wives married to Timbaki locals and it is hoped that if sufficient pressure is brought upon the authorities, the community will acknowledge that problems do exist.

Timbaki is, undoubtedly, a working town. But it is also the home of many of those involved in the tourist trade of Aghia Galini and the surrounding area.

In the summer months, buses full of tourists will stop here for refreshments, accommodations and supplies before continuing their exploration of the southern coast. Its bus station has connections to other places of interest, and, if locals are to continue their involvement with foreign visitors – and seek their return – then individuals like Janet should continue to pressure the authorities for the good of the community as a whole.