The Greek islands are renowned for their beguiling charm. They are characteristically acclaimed for their pebbly, inviting beaches, their pale clear waters surfused with aquamarine, their chalk-white homes lining well-swept streets and their exuberant, hospitable inhabitants. But one almond-shaped island, lying just north of Mirabello Bay off the northeastern coast of Crete, holds no such alluring attractions. It is barren and dry and has, for the last three decades, been definitively abandoned. Nonetheless, to the astonishment of everyone who happens upon it, this island too has a palpable and lingering beauty. And curiously enough, it still reverberates with the discernible rhythms of its former anguished life. The last inhabitants of the island were confined there for life sentences from 1903 through to 1957.

Their reported escapes involved setting out by night in wooden bathtubs filled with clean dry clothes and fresh food and water, in a lonely attempt to reach the nearby mainland before dawn. Yet they were neither convicted criminals nor political exiles. Their plight was far worse. They were lepers condemned by their fatal disease and confined by government decree to the island of Spinalonga, thought to be the last leper colony in Europe until the recent reveiation of one in the Romanian Dobruja.

It is not known precisely when leprosy was first introduced to the Western world. Some have theorized that Hippocrates’ reference to uthe Phoenician disease” may indeed have been leprosy. Some suggest that the contagion was carried to the West by the armies of Alexander the Great after his campaign in India in 326 BC. Pliny states that the returning army of Pompey first transported the disease to the Mediterranean in 62-61 B.C.

In 1903 Crete suffered an alarming increase in leprosy cases. Leprosy is a dreadful illness marked by multiple nodules, muscle paralysis, bleached and scaly scabs, progressive deterioration of parts of the body and severe disfigurement of the nose, mouth and throat resulting in hideous deformity. While it was known that it could only be communicated after prolonged and intimate contact, and indeed that some were not susceptible to the disease at all even after sexual contact, it was thought thai the only reliable method to eradicate the disease was complete isolation of the victims. The insular colony of Spinalonga thus became the final refuge for leprosy in Crete.

Historically, leprosy was thought to have been an affliction of the soul as well as the body. The close nexus between leprosy and sinfulness persisted in literature. Reference to that association is found in Leviticus 13:44-46:

“Now whosoever shall be defiled with the leprosy and is separated by the judgment of the priest, shall have his clothes hangingloose, his head bare, his mouth covered with a cloth, and he shall cry out that he is defiled and unclean. All the time that he is a leper and unclean, he shall dwell alone without the camp.”

References to sexuality and leprosy also appear in Shakespeare. Leprosy is described as venereal in Timon of Athens. With a pun on the word “whore1′ Timon observes that gold used to buy a woman, will make “the hoar leprosy adored.”

Prior to the establishment of Spinalonga as a leper colony largely because of the stigma of sinfulness and immorality associated with the disease, the lepers of Crete lived furtively in caves or were clandestinely cared·for by their families. Kazantzakis relates that many Cretans were ashamed to admit that a relative was afflicted with the disease and consequently would lock the victim in a room in a remote village.

When these lepers were discovered by the authorities, they were removed, despite clamorous family objection, by force.

The degree of undiminished loyalty exhibited by family members when victims were wrenched from them is illustrated by the story of one resolute Cretan wife who refused to part with her ailing husband. She cut fresh wounds in her own flesh and transferred into them the discharge from her husband’s sores. When the boatman transported the pair to Spinalonga he simply assumed that they were both diseased.

Spinalonga lies just off shore, close to the coastal resorts of Aghios Nikolaos and Elounda. Spinalonga is easily visible from the quay at Elounda and a short boat trip takes the visitor to the rocky, oblong island.

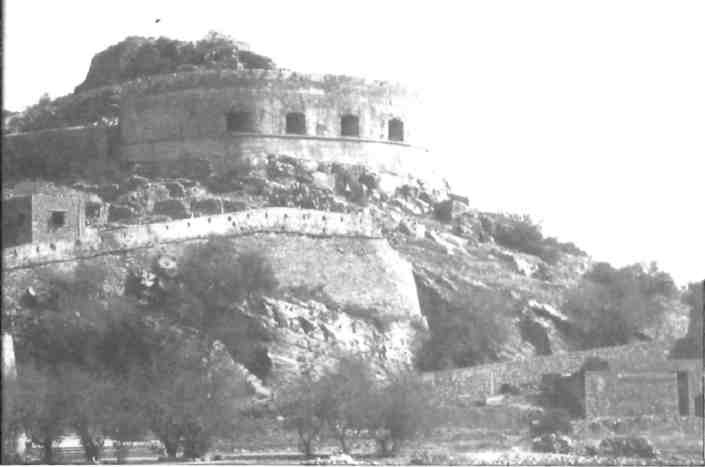

The island still appears impregnable because of the imposing, well-preserved walls of the fortress, once reputed to be among the most formidable in Crete. It was built by the Venetians and later used as a refuge by Christians fleeing the Turks. In 1715, however, the Turks conquered the island and the fortress became a Turkish stronghold. At the end of the 19th century, just prior to the establishment of the leper colony, there were about one thousand inhabitants on the island, all of whom were Turkish. They fled when the lepers began to arrive.

The origin of the name Spinalonga has long been disputed. Some suggest it is a Venetian word meaning “long arm”. This term would describe the whole peninsula, which once extended like an arm into the bay with Spinalonga as its fist. In 1897 the French cut a small canal and the fist became the island. Others believe that Spinalonga derives from the Italian for “long thorn1′. The most plausible explanation, however, is that it is a Latin transliteration of the Greek ‘phrase “Stin Elounda”. In early Venetian times it was in fact called “Stinelonga”. Unfortunately, the name Spinalonga no longer appears on the official maps of Greece: In 1954 a group of pedantic bureaucrats officially changed its name to Kalidon. But the fishermen of Mirabello preserve the island’s medieval name.

The lepers started arriving on the island in 1904. From that time until 1926 over 700 were transported there. The majority of them died; but a handful recovered and a few actually escaped. Half of the 40 children born on the island also died there. The healthy infants were removed and placed in orphanages in Athens where modern medical treatment substantially improved their condition.

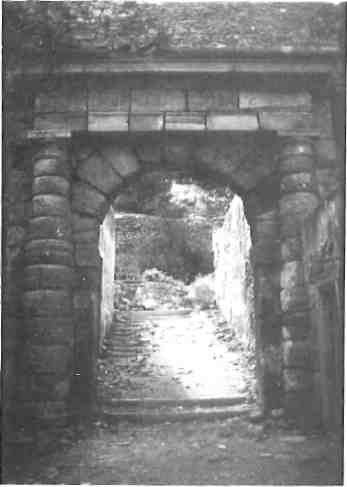

While the island shows the effects of over three decades of neglect, much of it still remains as it was when the unhappy residents lived there. It shows touching evidence of typical village life as it was in the first few decades of the twentieth century. The doors of shops, homes and the hospital gape open. The remnants of the lepers’ sojourn lie scattered all over the island – the bread ovens, the cupboards, the discarded tools, and even a basket or two.

Surprisingly, the village was reputed to be more affluent than the surrounding villages on Crete, for the lepers received generous pensions from the government, while the surrounding villagers were farmers whose fields yielded sparse harvests.

Those who found work in the leper colony were regarded as fortunate. They worked as boatmen, nurses, cooks or laundry workers. There was even a projectionist for the cinema.

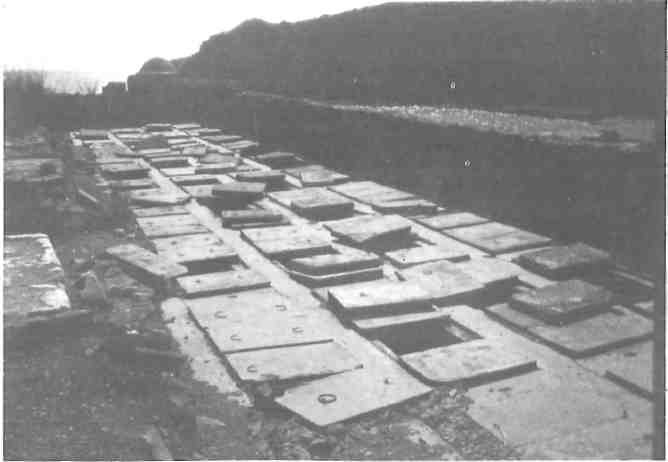

The remains of the village today include the marketplace, a stone quarry, two churches, the washhouse, cisterns, the fumigation center, a hospital, the pharmacy, the old stone houses and the cemetery which has individual graves for those who could afford burial, and communal graves for the poor.

The spirit of the diseased still pervades the tiny island. Its presence is felt particularly in the cemetery, where rows of uniform stone slabs mark the graves of the .dead. Some of the rectangular slabs have been knocked askew, exposing the sunken earth below, where the whitened powdery bones of the lepers are eerily visible.