Among the hairy, rank-and-file bracelet weavers, and barrowfuls of the latest Soula Boula cassettes, ingenious vegetable shredders, Athens ’96 Olympics T-shirts and other trappings of modern Athenian existence, a tinkle of a bell or a cry of “salep!” may, now and again, snap you out of your rat-race reverie.

You have stumbled on a tradesman of the old school, an unconscious upholder (“…but why do you want to talk to me?” was the stock, incredulous response) of unsung traditions.

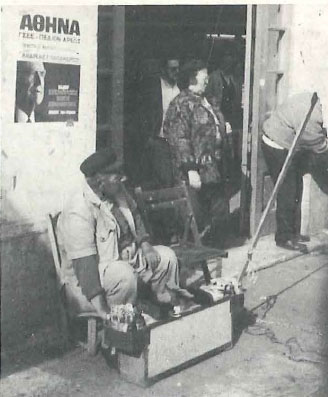

The first lesson I learnt in my search for the tradesman of the past was that any deliberate attempt to sniff one out is practically useless. Although you are certain you have seen one a hundred times before in a particular spot, like the proverbial watched pot, he stubbornly refuses to materialize when needed. However, after several fruitless trudges around the city centre, one morning I came across my first shoe-shiner, slumped right outside Monastiraki metro station, busily scrubbing away at the feet of a man who turned out to be a Greek journalist.I watched, and it soon became obvious from the frequent brush-dropping and polish-smudging that the man was a little the worse for early morning (nine o’clockish) ouzo!

“Would you mind if I asked you a few questions?” I venture.

“Wha’d’she wan’?” he slurs at the Greek journalist.

“She wants to ask you some questions. The girl’s only doing her job,” he winks at me, “You won’t get much out of him, he’s well gone. Why don’t you try the corner of Pireos Street and Omonia? There are usually more down there.”

“That’s right,” growls the shoe-shiner. “Try Pireos, Thousands of them down there, damn them! And I s’pose your shoes are plastic, too? Damn plastic shoes! You wan’ to buy a lacheio!”

So I buy a lacheio (his more lucrative side-line) and set off for the street of a thousand shoe-shiners. And there, sure enough, are two of them, sober and stern as judges, on the pavement outside the Asty Hotel. I choose the one with the traditional brass box (the other has only a tatty blue wooden one), and decide to give my (leather) ankle boots a spring treat.

“Can you clean these?” I ask, unsure whether it is really the done thing for a woman to have her shoes shined.

“Sure,” he says, and gestures to the foot-shaped stand on which I obediently rest my shoe.

Rolling up the bottom of my jeans, he inserts pieces of rubber-backed canvas and cardboard into the tops of my boots to protect my socks, and with a cloth begins to remove the loose dirt.

“Can I ask you a few questions about your job?”

“It’s obvious, isn’t it?”

He finishes his dusting, and produces a plastic bottle of brown liquid polish from the box under his seat: the brass-topped bottles in his shoe-shine box are merely for decoration, it seems.

“Well, what about your box? Where does it come from? Is it Greek?”

“No it’s Turkish. They bring them from Turkey. They’re very expensive, you know.” (In fact, in Monastiraki, one will set you back about 80,000 drachmas.)

He begins to apply the frothy polish with what looks like a large toothbrush.

“And what about you? How long have you been doing this?”

“Twenty years.”

“And do you come to the same spot every day?”

“Yes, Fam always here.”

“What’s business like these days?”

“Oh, fewer customers, every year much fewer.”

He brings out a different brush and buffs over the polish, then brings out another plastic bottle.

“Varnish,” he says, and my boots begin to shine as they have never shone before.

“Do you have many colors?” I ask.

“Fourteen. Reds, blues, greens, purples, everything.”

The treatment is almost complete. Just the finishing touch, with two large soft brushes which he sweeps rhythmically back and forth. I thank him, and as I scuttle away I can’t stop staring at my miraculously rejuvenated boots.

These days, when a bottle of shoe polish costs about the same as a full shine (200 drachmas), shoe-shiners are few and far between in Athens. Apart from the Monastiraki man and the street of a thousand (somewhat dwindling in numbers) shoe-shiners, other spots to try if you feel like giving your shoes an old-fashioned treat are the corner of Alexandras and Kifissias Avenues, and the centre of Pangrati.

There are two organ-grinders left in Athens. Less elusive than the shoe-shiners, one or both of them can usually be found during shopping hours around Ermou Sreet, and both seem able to ply a reasonable trade, mainly from generous female shoppers. They wheel their laternes (barrel-organs) around on large solid-looking trolleys, adorned with gaudy floral material and plastic flowers. Laterna is the generic term these days, though in the past it was used only for the type of barrel-organ that was carried on the grinder’s back: the pushed variety was known as romvios. The organ itself is contained in an intricately carved wooden b ox, and traditionally bears a 1940s style portrait of a naked young woman in a woodland setting. It is supposed to be Genevieve, the pure and lovely heroine of a folk legend who was banished to live amid nature for several years.

The first organ-grinder I came across was not in the mood for talking: “I can’t talk now, Fm working!” he explained, obviously agitated at being interrupted in the serious business of turning his handle steadily. I drop some money in his collecting dish, take a couple of grudgingly permitted photos, and pin my hopes on organ-grinder number two. He is definitely more cheerful and less perturbed at having his handle-turning interrupted when I bump into him about a week later at the bottom end of Ermou.

“And why shouldn’t you take a photo of me? Others have taken videa” he boasts, giving the word a Greek plural ending. “Yes, Fve been doing this job for many years. Many, many years. And before me, my father, and before him, my grandfather, and then his father. Look at the instrument! It is 140 years old, and still good as new! Every night I look after it, clean it. Maintenance, you know.”

I look suitably impressed. “It’s very beautiful. And how does it work?”

“Oh, inside it’s something like a piano. I turn the handle, and that turns a wheel inside that hits different pieces of metal. And I’ve got many tunes. Good old tunes…”. With a jingle of his bell he’s back in action, a strange anachronism in a glossy jungle of Italian shoes and designer maternity wear.

“Anne, come downstairs! There’s a ‘dying trade’ going past!”

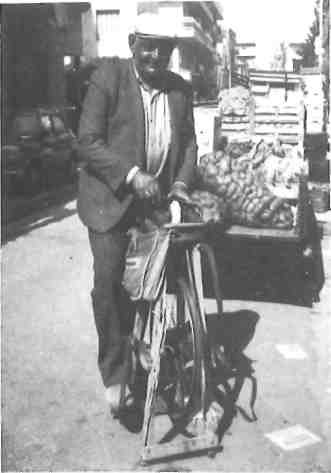

My husband’s voice came up through the intercom one day afternoon. And sure enough, there he was, setting up shop outside my local greengrocer’s in Vyrona, drawing a cluster of curious schoolchildren: the knife-grinder. I hastily grabbed a handful of kitchen knives and went out to join the excitement. He had picked a good spot: housewives shuffling into the house with their vegetables, came out again with their knives and scissors. In the space of an hour and a half, he must have made about two thousand drachmas. But it was an exceptional hour and a half – in the days of electric knife-grinders and cheap disposable knives, he is as much a curiosity as anything else.

Smartly dressed in pin-striped trousers, grey jacket and white cap, he poses proudly for my photos.

“Do you know how many people have taken my photo?” he asks boastfully.

“Yes, I’ve been doing this job for many, many years.”

His sun-scorched skin and rough hands are a testament of this. I give him my two Sheffield steel meat knives.

“Ah!” he sighs, with the air of one who has been forced to compromise his standards, “Now these are real knives! Excellent quality knives!” he says, and his foot begins to pump away at his treadle.

“Will you bring me one of those next time you go abroad?” asks my Cretan greengrocer.

“Sure,” I say, confident that he will have forgotten about it by then.

“Only,” he adds, drawing his traditional Cretan knife from his pocket, “I want it with a handle like this!”

The knife-grinder pedals, propelling the big bicycle-type wheel that turns the grinding wheel, and sparks fly. Then comes the second part of the process. He strokes my knives backwards and forwards across a flat piece of granite which is greased with motor oil.

He hands them back to me: “You be careful with them,” he cautions. “They’re dangerous, those knives.”

Ten minutes later, he’s off again, his grinding machine strapped to his back, with a cry of Mahairia, psalidia akonizo!(“I sharpen knives and scissors.”)

If he should wander into your neighborhood, a large meat knife will set you back 150 drachmas, a pair of scissors 200 drachmas.

Of all the traders I was determined to interview, the salepdzis (the seller of a thick, nourishing drink called salepi) proved to be the hardest to track down. Now numbering only four or five in the entire Athens/Piraeus area, they seem to sell salepi only during the cooler months. Then you might catch a glimpse of one in the early hours of the morning on the corner of Athinas Street and Omonia Square, their traditional haunt, catering to nightclubers and early risers alike, or at mid-morning around the junk shops of Monastiraki. The butchers at Athens meat-market, another common winter hang-out, agreed that it was the wrong season for salepi: the salepdzis they knew was selling ice-cream now, they said.

But in Piraeus I was lucky. I had gone down to see some friends off to the islands early one morning, and there he was, a real salepdzis, right in front of my friends’ ferry, sitting on a wall contemplating his steaming brass briki (salepdzis jargon for ‘large tea-pot’), no doubt lamenting the eclipse of a time before the advent of Coca-Cola, instant frappe and other such synthetic stimulants.

“Do you sell salepi?” I ask shyly.

“Yes.”

“I’ll have a cup, please.”

“Large or small?”

“Well, how much is a large one?”

“200 drachmas for a large one, 100 for a small one.”

I plump for a large one, and he raises the enormous briki from the small charcoal stove that is installed in the front part of his trolley, dispensing the steamy, syrupy liquid expertly into my plastic cup and then adding liberal shakes of cinnamon and ginger.

“Be careful. It’s very hot,” he warns.

“Do you mind if I take your photo?” I ask. He’s more than pleased to pose, and I promise to meet him the following week to give him a copy. And how will I find him? He starts his day at the Piraeus metro station, where time-pressed commuters are his prospective customers between 5 am and 8 am. After that, he sets up shop on the quay next to departing ships, half an hour or so before they are due to sail, and in between he is around the meat-market.

The drink seems to have a curiously vitalizing effect, dragging me out of my early morning drowse. It is a magical brew.

“Can you tell me your secret? How do you make it?”

“Well, just half a teaspoon of ground salepi – it’s very expensive — 7000 drachmas a kilo. You can buy 50 or 100 gram quantities from herb shops along Evripidou Street. You mix them all up over the fire, until it begins to thicken, and there you are.”

The ground salepi powder itself is derived from the dried roots of the early purple orchid, now quite rare but previously common throughout Europe and Asia. In Greece it is still found high in the mountains of Macedonia, Epirus and Thessaly, where it is picked in spring and left to dry in the sun. The ancient Greeks attributed aphrodisiac properties to it and used it in fertility rites because its double ovoid shape resembles testicles – the word ‘orchid’ is actually derived from the ancient Greek ‘orhis’, meaning ‘testicle’. Later, the Victorians also used it as an aphrodisiac, while in Turkey and Greece it became renowned as the base of a soothing, warming beverage, beneficial to the throat and stomach.

In fact, the salepi tubers contain a starchy material called ‘bassorin’ which is said to be more nutritious than any other single plant product. Just 25 grams of the root are enough to sustain a man for a whole day.

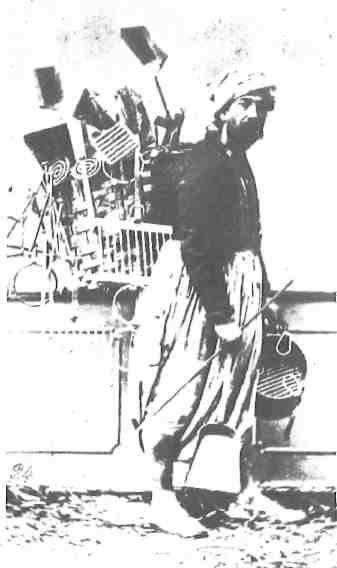

Salepi-selling in Greece reached its peak during the 1930s and 40s catering to the tastes of Greek refugees from Asia Minor – home of the reputedly best salepi – and Istanbul (where it still is popular today, but made with milk rather than water). In those days, a salepdzis would carry the bulky brass pot strapped to his back, and a container of water in his left hand. Around his waist he wore a kind of belt to which glasses were attached, and he would rinse each of the glasses out with water after use. Since the 1950s, however, salepi-selling, like other street trades, has been on the decline, and one cannot help but wonder whether these rare and colorful reminders of the past will still be walking our streets in five years’ time.

Basket vendor

Hawker of kitchen utensils