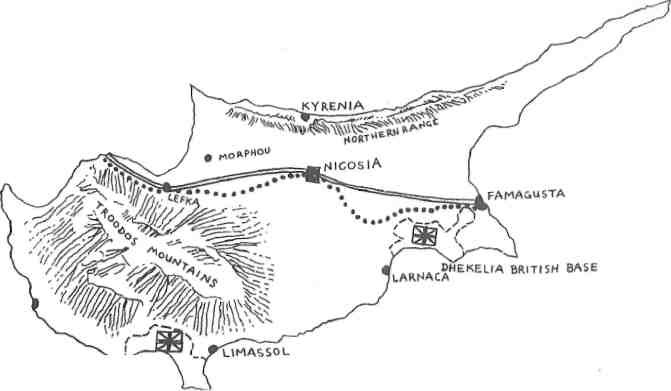

The 180-mile-long Green Line, brazenly revealed by rusty coils of old barbed wire and armed Turkish troops, slashes the island of Cyprus from Morphou Bay to Famagusta. The desolate buffer zone, patrolled by the United Nations Peacekeeping Force, tracks the demarcation, widening the gash in more populated areas. In remote villages the neutral zone narrows and merges imperceptibly with no UN troops in sight.

In the village of Lymbia, southeast of Nicosia, high on a summit overlooking expansive unkempt fields circling the seized village of Louroujina, you can straddle the Green Line, one foot on Greek Cypriot soil, the other on occupied ground. For this distinguishing feature, along with the perception that no rational person would expect several thousand women to attempt to confront controlling troops on this unlikely precipice, Lymbia was one of two carefully chosen sites for a major peace demonstration by women in March 1989.

On the drive from Larnaca airport to Nicosia, I looked for traces of the Green Line but saw nothing in the darkness. I arrived in Nicosia just after midnight with one of the Cypriot organizers. She darted down short, busy streets then abruptly turned into a narrow barricaded area flooded with light.

She pointed upward, then slowly turned the car around.

Seven or eight Turkish soldiers were standing guard atop the ponderous Venetian walls that encircle the old city. They gripped semi-automatic sub-machine guns diagonally across their chest. Their attention was unmistakably fixed on our unauthorized Fiat. One of the soldiers jerked his weapon spasmodically toward the exit to which we were heading. A small guardhouse loomed above the wall. The flag of the Turkish Republic, red with a bleached white star and crescent, noisily flapped in the shameless spring breeze.

Are they ever unmindful, I wondered, as I watched the engaging Cypriots that night in the sidewalk cafes and pubs; are they ever forgetful, for just a fleeting moment in the prolonged 15 years, of the constant intrusive presence of the occupying Turkish troops?

On 15 July, 1974 the right-wing junta in Greece forcibly seized power in Cyprus by toppling the government of Archbishop Makarios. The express objective for Cyprus was enosis, or union with Greece. Cyprus has been an independent state since 1969, when the island ceased to be a British protectorate.

On July 19-20, the first Turkish shock troops landed on the island’s north shore. The stated rationale for the invasion was the protection of the Turkish Cypriot minority in the unrest following the coup.

On 22 July the Athens junta that initiated the coup began its rapid fall from power. The demise of the Greek irredentist forces in both Athens and Nicosia was complete by 14 August. The rationale for the first Turkish invasion thus lost plausibility.

Turkey nonetheless maintained that it was still acting to protect its minority population. In a swift and well-executed advance from 14 to 16 August Turkey invaded 34 percent of the island. Coincidentally, the advance halted on a line that corresponded precisely with the demarcation that Turkey had urged, and the UN mediator had rejected, as the border of proposed partition in 1965.

The Green Line places the ports of Kyrenia and Famagusta within the zone and severs the capital of Nicosia nearly in half. This area had provided more than two-thirds of the Republic’s cultivated land, most of its major tourist attractions, and about 60 percent of water resources, mining and quarrying. The Green Line is still in place today, 16 years later, precisely where the Turkish advance halted in the summer of 1974.

To examine the Green Line in the revealing light of day I met Polys Kyriakou in the neighborhood where he grew up. We walked past war-torn homes pockmarked with bullets. Neglected, elongated shutters that had once been painted a glossy green or blue were now bolted closed. Occasionally we passed an opening with a shutter dangling by a single broken hinge. We peered into a cavernous hollow.

The area around Aghios Kissianos runs nearly parallel to the demarcation that dominates the devastated neighborhood. Everywhere there are reminders of the division. At each turn we saw armed soldiers, Greek Cypriots, Turks or the UN. All streets were blocked and barricaded with barbed wire.

Polys native Cypriot accent allowed us to move close to soldiers on guard at the perimeter. We spoke in hushed tones. Two soldiers in the guard post were only 18 years of age,just out of high school, infants at the time of the invasion. Just a few months before, one of them told us, a fellow Cypriot soldier was shot by the Turkish soldier he had ordered out of the buffer zone that ran alongside the guard post at which we were standing. Only the UN is permitted in the neutral zone. These guard posts in and around Nicosia have since been removed to avoid similar outbreaks of sporadic violence.

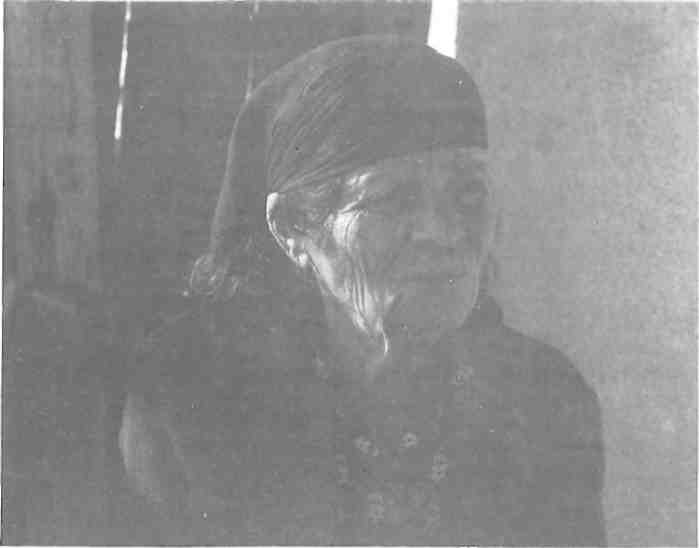

A round old woman with smooth white hair shuffled beside us. Polys recognized her as the mother of an old school friend. They quietly reminisced. Her face bore an expression of profound loss as she spoke of her lost and scattered family. She was a woman living on the edge of disaster”. When we die,”she said waving toward the few homes scattered on the street,”there will be no one, just the soldiers and the guns.”

The morning quiet was brusquely jarred by sounds of life from across the Green Line. The amplified call of the muezzin summoned the Moslems to prayer and drowned out all other sounds around us. The old woman made the sign of the cross and slowly turned toward home. She carried the small plastic bag of bread that she had just purchased from the one remaining neighborhood baker.

On 8 March 1989, eleven days before the scheduled march, the Women Walk Home organizers sent a letter to the UN in Nicosia and to the Ambassadors of the permanent member nations of the UN Security Council. It read, in part: “Our walk will be a non-violent protest by women against the restrictions imposed militarily on all Cypriots.” The women expressed their collective frustration and stated that after years of “patient waiting” the women “have begun trying to walk home.”

The day before the march the headlines in Cyprus newspapers read, “Hundreds of women to dodge mine fields.” The newspapers quoted Rauf Denktash, leader of the Turkish Cypriots. He warned that marchers would be arrested if they crossed the Green Line. Moreover, Charles Gaulkin, the spokesman for the UN, urged that they would affirmatively prevent women from entering the buffer zone. The news reports that minefields were sown in many parts of the Green Line were of particular concern to the women. There were concerted efforts by outside forces to pressure the women to cancel the march.

Prior to the 1974 invasion, Famagusta had been a thriving seaside resort. It was known for its alluring hotels on the littoral and its fine sandy beaches. Turkey reportedly had no intention to occupy the city in its August 1974 advance, but when they reached Famagusta they found it empty. Residents had fled south to seek safety. Since the war the city has remained uninhabited,, frozen in time under the hot Cypriot sun. It is widely believed that if and when resolution is achieved, Famagusta will be the first area to be repatriated.

Katerina Savvidou was nine years old that day in August when Famagusta was occupied by Turkish troops. The day before the march we went to Dherinia to get as close as permitted to her childhood home. From a rooftop in Dherinia we found the view we were looking for. With binoculars and a tele-photo lens she pointed to her home, half-hidden behind a long low elementary school. On the day her family fled, she recounted, her mother paused to water her flowers for the last time. And her father insisted on opening the windows so the glass would not be shattered by the bombs.

The invasion left some 200,000 Cypriots without homes and an estimated 1619 are still unaccounted for. Many of the missing were photographed and identified as prisoners in 1974, but they have not been seen or heard from since. In 1974, in a central square in Nicosia, relatives would assemble to hear news of their missing loved ones. An official flatly read the daily list of names. After each one he would report their status as wounded or prisoner or dead. Women wailed as the names of their fathers or husbands or sons were read. Many of the Cypriot men were taken to prisons in central Anatolia. Katerina’s father was one of them.

March 19, the day of the march, was a bright clear Sunday. A caravan of more than 98 blue tourist buses, each carrying over 50 women marchers, left Solomos Square in Nicosia for a destination known only to the few members of the committee of organizers.

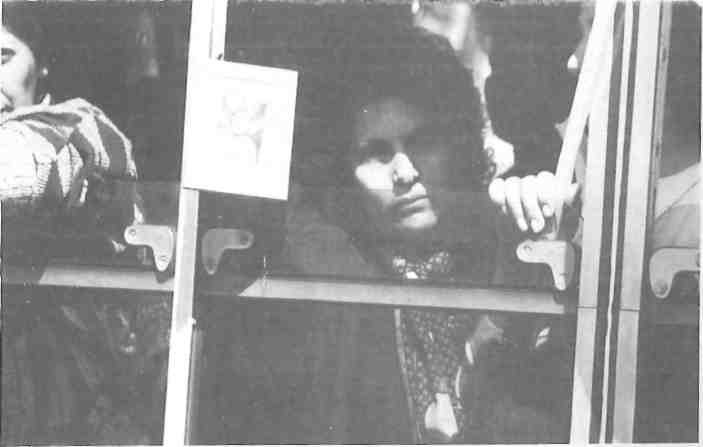

The streets of Nicosia were lined with people; children ran toward the buses with bottles of cold water and handed them to the women through the open windows. The women within the buses held white flags that draped through the opened windows. A woman in the bus alongside held up the black and white photograph of a young mustachioed man in a military uniform. She was dressed in black, her eyes deadened with 15 years of grief.

Cypriot men having coffee in the outdoor cafes shouted, “You will do what we have failed to do.” The women in the buses shouted back, “We walk for you.”

Strict rules governed the march. No food or drink in the buses or on the march. No purses, no national symbols such as flags or banners. Only white flags were permitted and the only banners read, “We Come in Peace.”

Each bus had a leader and her instructions were to be followed during the trip and during the walk. The rule that was reiterated was “No talking” once the walk starts. The women were to remain silent at all times.

While the buses moved out to the countryside, the helicopters overhead closely tracked our direction. The women in the bus grew silent. I watched while we approached an intersection southwest of Nicosia. The 50 or so buses at the head of the line turned right. The bus ahead of us turned left and we followed, along with the 40 or so behind us. The women in our bus were convinced that we were part of the decoy group. We had heard that it was conceivable and quite probable that the large group of buses would separate into two or three groups to distract and frustrate the Turkish surveillance. Every effort was made to conceal the actual destination until the last possible moment so as to maximize the chances for crossing the Green Line en masse.

What the women did not learn until later was that there was no decoy group. There were two separate and simultaneous crossings of the Green Line at villages less than ten miles apart. It was only in the afternoon at Lymbia that I learned from a Danish reporter that another demonstration had succeeded a few miles away.

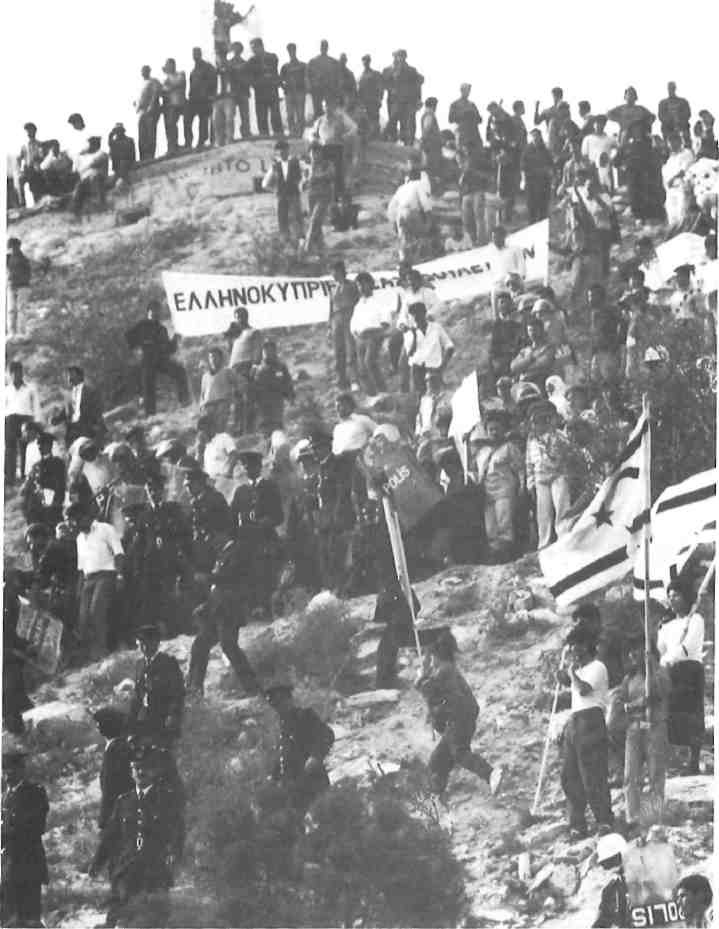

When our bus stopped, our orders were to”Run!” I looked in the distance to a steep cliff with a small whitewashed church at its peak. In front stood five Turkish soldiers in drab green fatigues. They were looking down at the 50 buses lining up below them, and at the ant trail of women heading directly for them.

We jogged up and around the steep hill and reached the crest, guarded by the soldiers. The crest was a wedge-shaped area, lined with barbed wire. Some women held the barbed wire down with their shoes while others climbed over. At the peak, which was also the Green Line, women were confronted with sandbags, behind which stood a now growing number of Turkish soldiers. Turkish reinforcements came up the hill from the opposite side.

There were, in less than half an hour, about 2000 women on that hill and surrounding fields. About 150 women were at the peak. More troops arrived, then Turkish police in formal navy blue uniforms and riot shields and clubs, then Turkish civilians from the occupied village of Louroujina with signs that were printed with remarkable speed that read, “Better apart than dead.”

When a battalion of Turkish policemen and women climbed the peak, the mood at the top was more apprehensive. The soldiers had at first tried to shove the women down but were unable to do so because hundreds more filled the paths below them. There was no room to push back. The Turkish police then tried to wedge them in a smaller space, forcing the women to move back somewhat. The UN futilely attempted to keep the women separate from the Turkish police.

“We can only hold back for about 20 more minutes,” the UN officer ahead of us gasped. “Please go down.”

After one particularly brutal push from a row of arm-locked Turkish police, a woman from England, in an astonishingly beautiful soprano voice, poignantly sang “The White Cliffs Of Dover”. Shortly thereafter, Turkish civilians brought a tape recorder and blasted out the Turkish national anthem.

More and more Turkish civilians issued from the village below. Some stayed in the fields holding banners in Greek and in English that read “No to the violation of our borders.” Some screamed vicious threats in perfect Greek.

These threats profoundly affected the older Cypriot women. “Like my mother before me,” one said, “in Smyrna,in Cydonia, the same words.”. Tragically, many of these women were from families of refugees who had been expelled from Asia Minor before and after World War I.

Later that afternoon Rauf Denktash, President of the self-proclaimed Republic of Northern Cyprus, arrived in Lymbia by helicopter. “If he came to us,” one of the women said, “perhaps he is one step closer to Vassiliou.” George Vassiliou, President of the Republic of Cyprus, had at that time repeatedly offered to meet Denktash in an effort to resolve the conflict. Denktash had spurned each offer and was content with the status quo.

At Akhna, a looted and deserted village six miles away, the rest of the women marchers occupied the church of Aghia Marina. The interior had been completely stripped and demolished. In the rubble they found a few old bibles, a letter in Greek and pieces of shattered mosaics. Inside the church the women sang “Adathistos Ymnos”, a moving Orthodox hymn. The last 22 women to leave the church, after being ordered to do so by Turkish authorities, were arrested and held for trespass.

For some of these women Aghia Marina had been their village church. They had been married there, baptized their children there and annually celebrated the resurrection there.

Some were seeing their homes for the first time in 15 years. They gathered bunches of purple anemones from the dry, abandoned soil. The wild blossoms were the only signs of life since the summer of 1974.

Fifteen years ago a Study Mission Report written for the United States Senate Counsel on the Judiciary correctly observed: “The longer the term required to achieve a resolution of the crisis on Cyprus, the greater will be the suffering of the people on the island. And it is the tragedy of Cyprus today that time is not on the side of peace… Until the central issue of the return of the refugees to their homes is resolved, there will be no peace for Cyprus.”

It is the tragedy of Cyprus then and now that time is not on the side of peace. The occupation has been in place for nearly a generation. Perhaps it is hoped that the fiery desire of Greek Cypriot s to return home will wane and die as the expelled generation grows old and is forced to find permanent homes in other lands. But the resolve of the Cypriot people is strong. Katerina’s grandmother will wait to return to her home until she dies. And her son after her. And then her granddaughter.