Wood has always been a beloved material in the hands of artisans who work it. It is as if Nature, through this material, worked its way through his hands up into the spirit of the woodcarver and filled him with the desire to create aesthetic beauty from the inspiration of the natural world around him. More than most crafts, woodcarving is self taught and its mastery dependent on instinct.

It’s a strangely itinerant craft. Often it is the massiveness of the mate rial which necessitates the artisan to go to the source of his craft rather than the other way about. In Homeric times carpenters we re called from place to place to build ships, cut beams for palace walls and hew roof timbers. The earliest effigies of the Gods we re made of wood xoana often said to have fallen from heaven. In later, more opulent times, the wood was vividly colored or plated in hammered gold. Divinity was thought to dwell in wood just as sacred groves of trees we re ‘full of gods’. In classical times, Athena was patron of woodcarvers and the profession was practiced under her specific instructions. This sense of the closeness of the material to the divine continued into the Byzantine era, and the places of Christian worship were filled with the woodcarver’s art.

Being a ‘live’ material, wood is also perishable, susceptible to all the shocks that flesh is heir to – and especially to fire. Though there are wooden houses nearly a thousand years old which still stand (or sag) in Constantinople, there is almost nothing of the woodcarvers’ craft remaining from ancient times, and little from the Middle Ages, either.

Nevertheless, woodcarving has been one of the most accomplished crafts of modern Greece, especially during the 18th and 19th centuries. It is as if during the dark period of Ottoman occupation woodcarving became an outlet by which the free spirit could express itself.

The craft may be roughly divided according to use into four categories: ecclesiastic, domestic, maritime and rustic. It is not surprising that the finest woodcarving is to be found in the most deeply forested areas of the country: the central Peloponnese, Mount Pelion, Macedonia and, above all, Epirus.

Yet there is a background of fine woodcarving on the islands of Chios, Mytilene and mainly Crete where the tradition is still lively. Constantinople, of course, was an important centre since it attracted woodcarvers from so many regions. The peripatetic nature of the craft led to the formation of strong guilds. Groups of woodcarvers often left their villages in springtime and did not return till autumn. This was true no t only of Greece but other areas in the Balkans and Asia Minor. In. cities like Constantinople they lived together in ghettos and spoke their own dialects to conceal the ir thoughts and feelings from their employers.

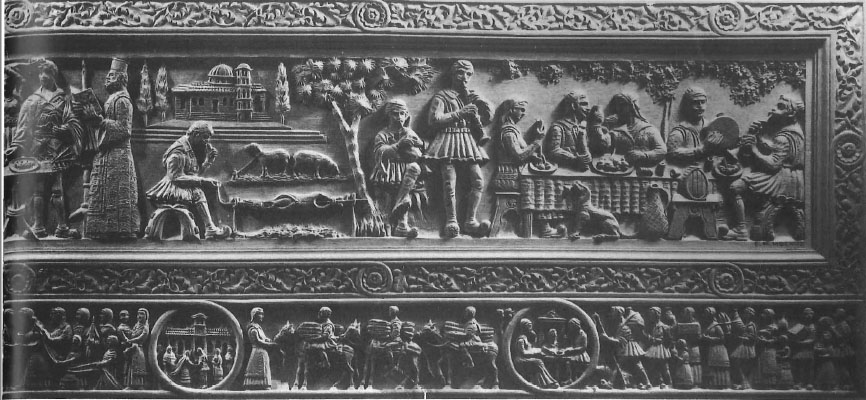

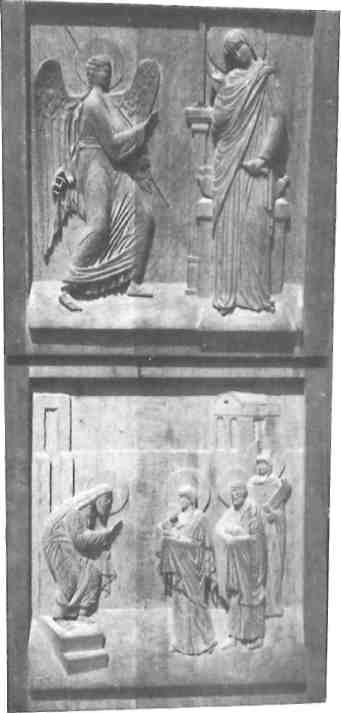

The interior decoration of churches reveals the woodcarvers’ art at its zenith. The seats, pulpits, chandeliers and the throne we re all carved from wood, but above a ll the iconostasis, or altar screen , separating the nave from the sanctuary. Originally it was low and usually made of stone or marble as can be noted in the early Byzantine style from Ravenna to Syria. But as the mysticism of Eastern Orthodoxy grew and the Holy of Holies became even holier so the iconostasis screening off the sanctuary itself grew taller, until it reached the ceiling. This architectural transformation suggested a lighter material, and eventually these screens, encasing the holy icons, were made entirely of wood. The earliest examples of these masterpieces of the woodcarvers’ art in Greece are the 13th century portal of the Monastery of the Panaghia Olympiotissa at Elassona and that of Saint George in Kastoria.

The wood most often used was walnut and lime. The tree was felled in winter when the sap had gone down into the roots. The lumber was then plunged into running water at regular intervals over the course of three to four years in order to ‘fix’ the sap and prevent the wood from warping. It was then left a time in the shade and later in the sun.

In the early ecclesiastic period, the decorations were simple and sparse and the bas-relief low. But as the craftsmen’s technique grew more sophisticated, imagination took wing and produced masterpieces. Not only did the decoration become denser, but the work grew more open and three-dimensional. This elaborate filigree and fretwork known as ‘carving on the air’, created open designs as delicate as lace.

The subject matter was either biblical or drawn from the lives of the saints, though elements of folklore were strong, too, with demons and spirits represented drawn from some mythical and atavistic memory; the most striking image of these was the snake-dragon symbolizing the evil principle, the domain of Hades and later of Hell, overcome at the top of the screen by the Holy Cross.

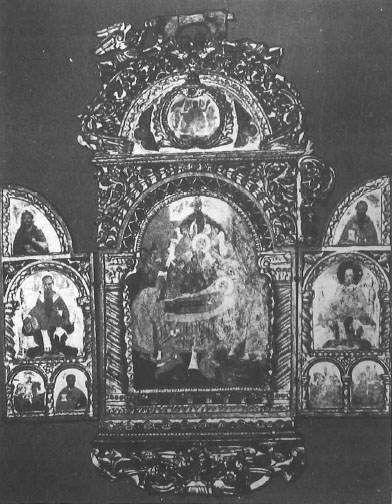

In the early days, carvers left the wood in its natural color, later they covered it with a compound of powdered zinc and glue. After it dried, they rubbed it with the dried skins of fish. Over the wood they then applied an adhesive called amboli superimposed with gold leaf, using a tool called a ‘cushion’ as well as the talon of an eagle. The gold sheets were usually imported from Constantinople and Smyrna. Vivid colors were also employed, creating a burst of joy amid the holy and solemn mysticism of the church interior.

Splendid examples of this art from the 17th to the 19th centuries can be found throughout the country though especially on Mount Athos. Among the most splendid examples of wood carved altar screens is that in the church of Saint Nicholas at Galaxidi. The master carver was Anastasios Moschos of Metsovo. Legend has it that he died at an advanced age falling from the top of the scaffolding, hardly had the screen been completed. Metsovo was then, and remains, the woodcarving centre par excellence in Greece. The iconostasis of the church of Aghia Paraskevi there is so densely decorated that it is said to portray all the animals on earth, ants included.

Examples of domestic woodcarving are rare in the early centuries of the Turkish occupation since the people were poor and furniture scarce. Even the houses of well-off merchants who traded successfully with the West had only the simplest and most essential furnishings, even when the panelling on the walls and ceilings were elaborately decorated. A major exception was the kassela, the chest in which the dowry of the daughters of the house was kept. Usually only the front panel was meticulously carved, though some had carved side panels as well. Most of these chests were made of walnut which the owner of the house provided for the artisans.

Woodcarvers would move into the villages of these merchants and stay for months. Some of the ceilings in these mansions were highly decorative. Around the central section of the ceiling, usually round or octagonal, painted panels were set. Other elements of the house which were carved were the lintels above doors, walls of the reception rooms, balustrades on interior balconies or lofts, and banisters along staircases. There are mansions like these to be found today in Macedonian towns, on Pelion and the island of Mytilene. Unfortunately, most of them have been destroyed by time, earthquakes or man, and many of the wood carved pieces have been sold over the years in the antique shops of Athens and Thessaloniki.

Fortunately, two superb rooms entirely wood carved from Northern Greece mansions have been donated to the Benaki Museum. The first has been installed piece by piece; the second is being assembled and not yet open to the public.

The decorations on all these panels were drawn from the artists’ immediate environment, everyday life, and as tradition has dictated: animals like the deer, the hare or the Byzantine peacock; cottages or urban panorama; vases filled with stylized field flowers. The cypress, most beloved among all trees, often adorned the dowry chests. These trees were painted in pairs and their tops inclined to each other in a gesture of embracing, surmounted with a little bird. This last was an idyllic scene, symbolizing the love which the future bride and husband would feel for each other. Part of the charm of these delightful scenes is the liveliness of the elements, for they are fine examples of naive painting. Other wood carved furniture in these households were beautiful cradles. Among the carved chairs, those of Crete are famous still, as are the stools of Skyros.

Another important category of woodcarving was derived from the long tradition of Greece with the sea. To this category belong the akroprora, the carved figureheads set into the prow of ships. Sometimes they represented the wife of the captain, but more usually an imaginative female figure, an ancient Greek goddess, or the Panaghia Gorgona (the Mermaid Madonna). At other times they represented famous warriors of Greek antiquity or the heroes of the War of Independence. These akroprora were painted in vivid colors and represented the spirit of the ship.

Rustic woodcarving includes some of the most familiar categories of folk art. It was most often created by shepherds, not by professional wood carvers, and the method of work can generally be called whittling. With their innumerable hours of solitude up in the mountains, shepherds with penknives pared sticks into pipes, spoons, needle-cases and magnificent distaffs for their womenfolk. On these they carved images of Saint George, patron of shepherds, as well as birds, crosses, symbolic animals and human figures. Another kind of popular rural woodcarving are the seals used for stamping special loaves of bread as church offerings and remarkable stamps used for printing on textiles, cut into floral decorations or geometrical designs. While shepherds whittled simple musical instruments like recorders, the carving of musical instruments occupied the most talented artisans.

In contemporary Greece, ecclesiastical woodcarving is flourishing once again. During the period between the two world wars, the architect Aristotelis Zahos, leading a group of artists and anthropologists under the motto ‘return to the roots’ started what has come to be called the neo-Byzantine style of woodcarving. Today, centres of this renaissance are found in Ioannina, Metsovo, Skyros, Crete, Thessaly, Mytilene, Rhodes and elsewhere. As they still say, ‘The skillful carver can depict everything that exists on earth.”

Interviews with Two Woodcarvers

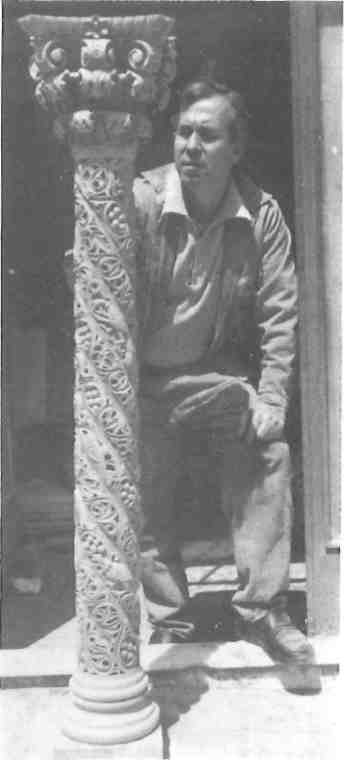

Evangelos Moschos, who has his workshop in Koukaki not far from Hadrian’s Gate, is the patriarch and master of an important guild of Attic woodcarvers. His reputation has spread throughout Greece not only because of a long artistic career in state or private professional schools, but also because of the excellence of his work. In admiration, younger woodcarvers call him ‘master’.

He was born some 75 years ago in the little mountain village of Dafnoti, in Epirus. His last name, Moschos, recalls the famous Moschos family of woodcarvers of the 19th century.

“Maybe we are a branch of that family,” he wonders.

Orphaned at a very early age, Evangelos had a hard childhood, and at 15 came to Athens to find a place in the sun. Talent and perseverance led him to the School of Fine Arts of Athens where he studied painting and wood-carving. He continued his career in Ioannina where, for several years, he directed the professional school of woodcarving which was located on the same premises as the orphanage where he had spent his early years.

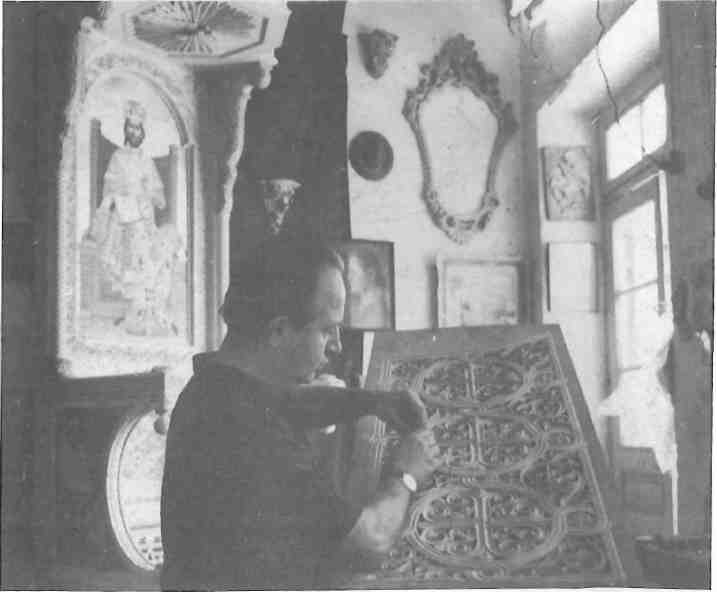

So attached is he to his work that at the age of normal retirement today, Evangelos does not do anything but work on wood. In his basement work-shop, far from the noise of the street, surrounded by all sorts of tools and piles of wood covered with layers of shavings and dust, he creates miracles, “I can work here,” he explains, “where I don’t hear even the flight of a bird.”

He demonstrates his series of tools, most of them fashioned by himself, some as fine as a needle. With them, he has mastered the secrets of wood. “I don’t go out in the evenings,” he goes on, “I like to spend many hours working here alone or with my assistants.”

On the ground floor, a magnificent wood carved fireplace mantle is almost finished. He has made it for the house of an industrialist in Preveza. Two columns and a central panel, all of them carved with flowers, birds, vine leaves and other decorative elements, give the impression that they will suddenly burst into life.

Against the wall two large woodcarved panels depict in the most unbelievably detailed way, daily scenes in a Greek village; “Memories from my childhood,” Evangelos says.

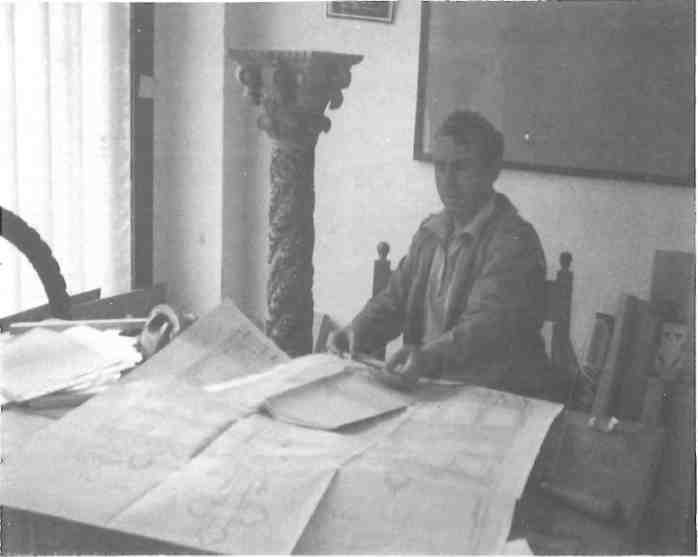

He is also preparing the designs for a church in Crete along with instructions to his colleagues there. He has done many carvings for churches all over Greece as well as abroad.

On the upper floor, where he lives with his wife and daughter, the rooms are choked with meticulously carved furnishings, chandeliers and decorative objects.

Evangelos Moschos is a phenomenon. During the many years he has been teaching privately or for the National Organization of Hellenic Handicrafts and its various branches around the country, dozens of wood carvers have learned this exquisite craft through him.

li don’t have the primitivism of a popular woodcarver because I have studied,” Evangelos admits, “but I do take many elements from popular art and blend them into my work.”

Much younger than Moschos since he was born in Athens during the German occupation, Giorgos Faliaridis is another very talented woodcarver.

“I wish to join this little branch with the hare, the deer and the peacock,” he said, pointing to a panel for a church, “in order that the whole depicts a unified scene from the woods, and not a vision without soul.”

Faliaridis, too, had a hard childhood, since he had also spent some of his early years in an orphanage in Mytilene.

Wood always appealed to him as a boy, and he began by learning to make furniture at a professional school in Athens. This inclination for carving propelled him to become a devoted assistant to two of the best workers in the craft at the time, Domenikos and Nomikos. While studying with them he won his first prizes for designing and making wood carved furniture.

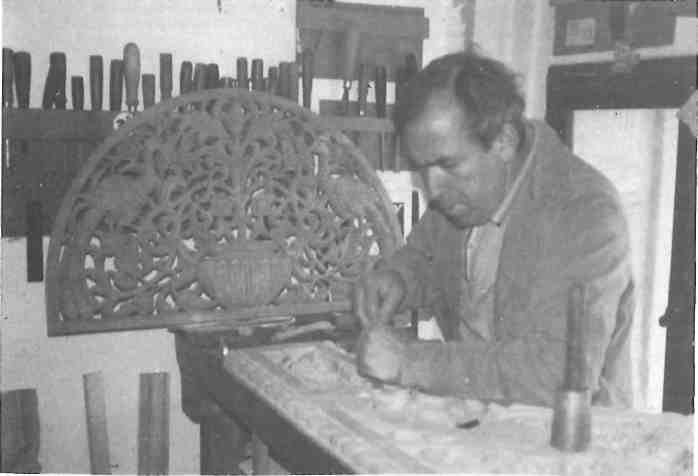

In his workshop at Vyronas, a worker and refugee neighborhood of Athens, Giorgos Faliaridis, lives and breathes with the song that wafts to him from the wood.

With excitement and joy he describes a two-month trip he undertook in a lorry escorting his work to Amman. It was an entire iconostasis, completely carved, executed on the command of the Patriach of Jerusalem for the Greek Orthodox church in the capital of Jordan.

Giorgos Faliaridis adores his work and regrets not having the time to achieve a style of carving which he feels he could give to portraits, and, most of all, to altar screens and other church decorations, not typical or traditional or standard designs, but following the richness of his imagination.

A close and attentive look at some of the carved panels spread out in his workshop reveal the true artist. All of them carved by hand according to the pierced style have a charming variety and an authentic line. No flower is the same as another, no animal climbing the branches of trees has the same standard appearance.

“Wood has a grain and if you go against it, you will have to throw the work away,” he says and he gives the impression that, in referring to wood, he speaks of somebody with whom he cooperates. “Wood is alive,” he continues, “and because of that I never repeat the same design.”

His son plays the violin and his wife has artistic inclinations too, but Giorgos is at his happiest when he holds a piece of wood and whispers to it and talks to it as he molds it. And the wood responds, freeing itself, and giving itself to him. This is the ideal love between the material and the artisan.

Many altar screens of his can be found in churches in Athens and elsewhere, as well as epitafioi, the biers which symbolize the Entombment at Good Friday services. Recently he finished the iconostasis for the church of the Virgin Mary at Paleo Faliron, which he undertook after winning the first prize for its design in a Panhellenic contest.

Now he is carving the iconostasis for the famous church of Faneromeni in Zakynthos which was ruined in the 1953 earthquake. Fie has also copied the exquisite wood carved frame of the icon of the Virgin from a photo of the original which is preserved in very poor condition in the museum of Zakynthos. His work is as gorgeous as the original.

Such are these two artisans, two woodcarvers, whose hands have wings and who converse with their material, projecting the most beautiful songs in the traditional rhythm of their ancestors.