An early Sunday flight lands its passengers on the northwest shoulder of Rhodes in a cool Aegean breeze and diaphanous sunlight. From the ragged bushy edges of the two-lane road leading from the airport to town one looks in vain for the familiar brochure vistas of Rhodes. There are merely a series of villages, a few bearing ancient names, with some glassy modernized shops and newly-added second storeys. When the shore comes into sight it is lined with large and small unpretentious hotels, the smallest ones decked in grapevines. Nearer the city, the first postcard cliche quivers into sight: beach umbrellas marching along the sand below the road in platoons varying in color and pattern.

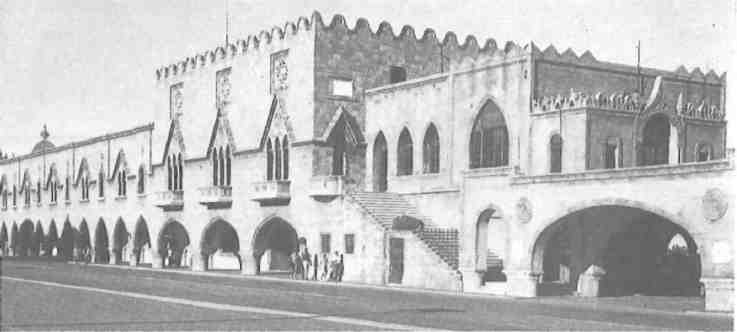

On the palmy Miami-like harbor drive, the first surprise: several huge buildings with massive pilings in front, round-bellied like abutments, their sand-colored porous stone suggesting seashells like the sort of material from which the temple of Zeus at Olympia is made. One is the city hall, another the courthouse, and a third a bank: all of them ‘Mussolini Gothic’. The massive walls, running within a stone’s throw of the three calm harbors, don’t at all snake around. Rather, they crush down upon the earth. They are handsome, at least seven meters thick, and the Mediterranean sun and winds have honeyed them. Were they of gray granite, rather than seabed rock uplifted technically, the scene would be Carcassonne. As they are ‘adopted Aegean’, perhaps they are acceptable as part of Grecian magic.

The smallest harbor has, fittingly, small boats, the second one moors the medium draft, and the biggest is dominated by three bulky white cruise ships that dwarf the historic windmills on the long broad mole. These pet windmills ground the imported grain to flour directly as it was unloaded into Rhodes’ always brisk harbor.

Cars and vans are roaring through the Gate of Italy. There is no pedestrian passage. But the Islamic name of the street – Al Hadef, meaning the Target – may be fitting. Though lined with trees and walkways and a few delightful plebian dwellings, it is a favorite channel for fast traffic. At its seaward end, the street planners have cut through the site of Our Lady of the City, leaving the desolate rear wall on the left and its apse and frayed vaults crumbling on the right. It is the lowest-lying sector of the City of the Knights. The downhill arm of a shopping/eating quarter winds through simple stuccoed buildings, and a plaza spreads around the bronze sea-horses of a fountain.

For swimming there is the ‘south’ shore. The town of Rhodes, long and vaguely arrow-headed, perversely points northeast. On the way there are shops, warehouses, small factories, junkyards. Gravelly paths skirting a wide bay branch down to the shore. Copious drains flowing out from concrete arches look suspiciously like sewer outfalls. A few local lads swimming; a picturesque schooner; a larger steel-hulled freighter: somehow the ensemble is pleasing.

The sun is overhead and bright. Circling back and climbing under the ilex grove to the stone glacier of a fortress, the road leads to the wide moat. (Never designed for water, the guide books say-) The immense protlate 15th century it was the most adv-anced military architecture in the world. The handsome coat-of-arms over the gate is one of some hundred escutcheons built into the two-and-a-half miles of the fortress wall. After we pass beyond another entrance with its bridge (the Tower of St. Mary), cheering is heard wafting through the pines from the east. Yes, it’s a Sunday afternoon: an intercity football game.

The stadium is white, and the gnarled pines reflect dark traceries over the seats. The turfed field is emerald from regular watering. The noisy crowd is 99 percent male. Messenia, by one point midway in the second half, is winning. The stadium is, of course, 20th-century. The ancient stadium lies outside the city in a bleak plain, below the three-and-a-half re-erected columns of the temple of Apollo and a square, rebuilt theatre. The ensemble marks the ancient acropolis, a site dusty and almost treeless.

Beyond the football stadium there is a preserve more opulently forested than any other ancient site. Passing through this Eden and the dark passage of the d’ Amboise Gate one finds oneself among the easels of portraitists and the booths of craftspeople under giant eucalyptus. At one of the half-dozen restaurants, explaining their ethnic menus by elaborate photo-friezes, it is time to order dinner and do one’s homework leafing through guidebooks and pamphlets.

“The ancient city of Rhodes had a heyday of only 250 years. But, of course, the three Rhodian cities that cooperated in its founding were part of the Dorian Hexapolis, so it is necessary to add their heydays, too.”

The Dorians arrived on the stage via Crete and the lower Aegean and got toeholds on Cos and the southwest corner of Anatolia at Halicarnassos and Knidos. No particular dates…they just succeeded the Minoans and the Mycenaeans … Oh yes, the Rhodians, probably a Mycenaean colony then, fought at Troy. The Persians subdued them in 490 BC and later they became a sort of vassal to Athens. Hardly a heyday- too long and diluted.

But they were tough sailors and traders. They really founded colonies, the old site of Naples, Gela and Agrigento in Sicily, Rosa in Spain, and something in the Balearics.

What makes a heyday? Culture …self-awareness. Sculpture…but of course sculpture was everywhere around the Aegean between 500 and 150 BC. The first nude female goddess-statue, that of Knidos, the Hexapolitan capital, was by Praxiteles. He was from Attica, but the Rhodians were rich from seafaring, they could get sculptors to settle. Chares did the Colossus. Two brothers did the Farnese Bull. And three sculptors together did the Laocoon group …stolen by Romans and rediscovered in 1506 in Rome.

The Colossus stood thirty-one metres high for only 66 years and then lay quake-felled for almost nine hundred. One hopes the revisualization is wrong, The Rottiers sketch shows the god Helios, patron of Rhodes, in an ambiguous crouch, holding his overhead torch sornething like an antique bomb.

Helios was of the Titan nature-tribe, not really Olympian, and had an important but tedious job: to drive the four-in-hand of the sun chariot.

Why had the Dorians chosen Helios? Were they closer to simple, natural forces? Did the civic identity of Rhodes congeal before Olympian patronage was fashionable? Did choosing Helios really have a connection to the marvellous sunlight of the island? Pheidias had him attend the birth of Athena on the east pediment of the Parthenon. His head, outstretched arm and wave-covered torso were in the extreme left angle; the waves were to show his rising from the eastern sea at dawn. A weathered plaster cast of this figure had rested, as of 1987, in a storage yard just to the south of the Parthenon.

Rhodes fell to the Persians, welcomed Alexander, successfully withstood one of those Macedonian generals who didn’t like the Rhodian alliance with the Ptolemies. The Romans dominated them, inevitably, and choked off the harbor taxation which had made them rich by declaring Delos a free port. Delos became a fabulous trade fair and slave market as a result. Then later, Cassius wrecked Rhodes and carried off, they say, 3000 works of art.

The Sound and Light show in the evening provides a medieval fix that raises more historical appetite than it satisfies. The mellow lights reveal the Palace of the Grand Masters above the piney slope. Although the English version is spoken in BBC voices, the selections from history have a French-fried flavor (after all, the Grand Masters were mostly French). The noble accents of grand masters and oaths of squires swearing obedience to the death are heard, and later the thunder of Turkish cannon.

The climax is the six-months’ siege by the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman ending with the capitulation of the knights. During the audio performance, lights ineffectually wink on and off in the few small high windows of the palace. Finally, the alternate stormings and defensive forays end with a “betrayal” by one Amiral, a Spanish knight, who as keeper of the stores quite simply kept informing the Grand Master that they had plenty of food and ammunition for a prolonged siege.

The self-defense of the traitor is interesting. The character says he did it for the good of Christianity, to start a new era, to put an end to the distortions brought to their religion by the knights. It makes sense. The knights were feudal, blindly aristocratic, and imperialistic. After definitively losing the Holy Land, they tried to conceal under their monastic robes their abiding greed and hunger for power.

Thus, after 213 years the knights lost Rhodes, but wrenched further existence in an island further west in the Mediterranean. The eccentricities of Don Quixote quieted their zeal considerably, but as the Knights of Malta they survive even now, harmlessly selling noble titles to Americans rich and nostalgic enough to pay knightly prices.

Sound and Light only mentions Greeks once: officials of the Greek communities, during Suleiman’s siege, beg the Grand Master to surrender under honorable terms because they knew that if resistance continued until the inevitable defeat, the Turks would massacre innocent Greeks as well as knights.

Down shop-lined Socrates Street, one makes for home under the moon, where dwells Helios’ sister, Selene…

Ahead are the harbors and the palm-lined Boulevard Eleftherias. Beyond a long block along the boulevard, and shaded walks, the New Market appears. Built by the Turks, it’s a charming antidote to Gothic walls: a polygonal compound of stores below and offices above. Its harbor frontage is an arcade with fingers of awnings and Marietta Pavlidis, director of the hundreds of tables for drinks and snacks.

The Tourist Information Office, handy to the New Market generous with maps and pamphlets, is run by two stylish, chatty women.

“From America? Oh, we have a lot of Americans living here, retired, you know.”

“Greek originally?”

“Yes…There’s an office behind the Dimarcheion that looks after their passports and so on. In every kafeneion you can find some; just ask. Or here’s a suggestion. Call this newspaper editor; he knows about everybody.”

She jots down a name, number and address. Since the morning is too young for serious sightseeing, it is better to stroll up into the ‘new city’ above the Mussolini-Gothic row, with its larger hotels, the Cathedral, the Prefecture, and the National Theatre, ending with the restored mosque and minaret of Murad Reis. Mandraki, the small harbor, sparkles in the morning light. The doe and the stag on their separate pillars at each side of its mouth are black silhouettes against the early sun. Beyond the mosque, the umbrella beaches begin long, glorious, well-kept.

Behind the Dimarcheion, in a prefab ‘temporary’ structure is the office of retired Americans. The name for them is omoyeneis, literally ‘same people’, thus stressing origins rather than experience abroad.

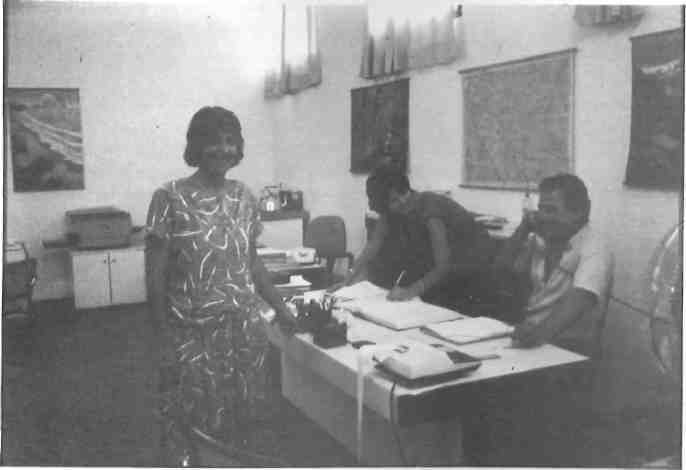

Marietta Pavlidis, is director of the Office for the Dodecanese Diaspora. (Yes, the word so frequently, even exclusively, used for the Jews, is a Greek original.) She herself is Greek-American, youthful, pretty, poised, and very informative: about 3000 Americans are in residence. But for a few Yankees, most are Greek-Americans. They display all sorts of residence patterns: some stayed put, others travelled often, others had the habit of returning to the US at certain seasons for longer or shorter periods. Many lived on retirement plans, but others worked at all kinds of jobs. Climate is perhaps the main card drawing them back, but Rhodian roots, serenity, and a safe environment are also strong reasons.

A return to reside in Greece, however, can be a Kafkaesque experience. It involves opting for dual citizenship at a Greek consulate in the US, translations of documents, verification by a Greek attorney in the place of origin, a final okay from Athens. Those with technical degrees deliver transcripts, but since recent graduates may be scared away by military service, Parliament is considering a shorter tour of duty to encourage young, educated returnees.

No Greek passport or voting privileges are allowed since such would threaten US citizenship. Another proposal in Parliament would increase the area around cities – to 15 kilometres in Rhodes, for example – where omoyenes can take advantage of development grants.

Might it not be nice to visit someone who has given up America? Marietta Pavlidis begins looking through her lists, and after obvious deliberation, offers three telephone numbers…

Beyond the New Market, the somnolent deer and the Aphrodite sanctuary, there is a door leading in to a medieval building near a massive uphill arch. It has no sign, but within is found a fascinating small collection of Dodecanese decorative arts. It is an immediate relief from the overweight Gothic edifices outside. A half-hour there slakes a thirst for Greek island motifs in fabrics, woodwork, metal objects and mousandra ensembles, carved and curtained wood frames for bedroom enclosures.

A big gate opening into a long cobblestoned space combining street and square leads to the telephone office. The first number given by Marietta Pavlidis introduces Mrs A. who immediately offers to talk on the telephone American-style rather than getting together. She was born in Rhodes and went to the States at the age of 15. When she returned from New Jersey two years ago, she had difficulty finding a job. Now she works as a secretary for a medical supply concern where her English is useful. Her husband expects to follow the family to Rhodes when finances are adequate.

With her are her daughter, 19, who works in a travel agency and also uses English on the job; and her son, 15, enrolled in a special ‘helping’ program to improve his Greek. Mrs A. laughs at this because she herself taught the Greek language in New Jersey. The family feels more independent in Rhodes, she says, and they appreciate the freedom from crime. Her son seems to enjoy basketball and soccer. They have a pleasant flat in a two-family house.

What do they miss in Rhodes? It used to be only US television and its variety. But now, with the new satellite programs, the tube is much better. Visitors from the US drop in frequently and thus Mrs A. keeps in touch with the land she left.

A second contact is a man living in Damatria, a suburb of the city. There is no answer. Maybe he’s on his US jaunt. A third contact lived way down on the ‘south’ coast, below Lindos, in Yenadi. The gentleman who answered said that Mr F. was in Ameriki. We have a lot of omoyeneis here.”If you come to us, you will find many.”

Meanwhile we must get the Knights and the Grand Masters under our belts, so let’s turn up the Street of the Knights, promising to come back for the Museum in the former Hospital another time. On this uphill cobblestone lane there are two and three-storey stone buildings presumably restored by the Italians. Some delicate windows and carved doors but principally the handsome escutcheons, relieve the prevailing grimness. The facade of the Inn of France and a chapel of the Virgin at the top of the slope are ornate. The Turks used the inns for quarters – for officers, probably – and built harem balconies.

At the top of the slope a portal and a series of great arches lead into the expansive forecourt of the Palace. The three entrance towers, at least four-storey high, glare in the sunlight. Inside is a huge courtyard surrounded by galleries above. At the first level of a two-storey staircase there is a chapel with a stone altar. On the altar a blank video monitor.

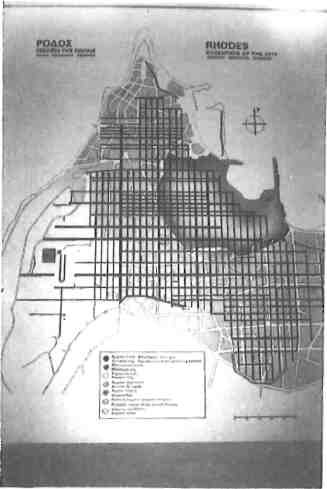

Charts and enlarged antique prints of the ancient town are exhibited in the next room. One map shows the ancient capital designed in a strict grid pattern by Hippodamos of Miletos or a follower thereof, and the later walls and precincts of the medieval city of the Knights. Somehow, the rectangles got lost in the two-and-a-quarter millennia of the city’s existence – the Street of the Knights and Socrates Street are the only decently long straight streets left.

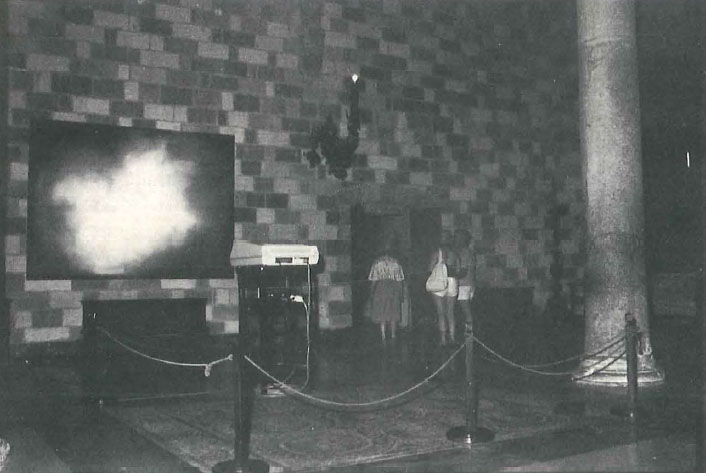

The great reception halls of the Pa-lace two flights up are Gothic-arched. Splendid mosaic floors brought by Italian restorers from churches in Cos, and now roped off from visitors, are in mint condition. The video in the chapel below has a partner here on one of the mosaics. An abstract artwork projects from it onto a screen. In almost all the various large and small rooms of the Palace are video screens with shimmering hues. In one large hall there is a post-expressionist sculpture of scarlet plastic. The knights host contemporary art exhibitions these days. The art is by Tsoklis, a prominent contemporary painter, and the exhibition is a pilot attempt to use the palace for something besides an attempt to revive history and an interest in medieval architectural aesthetics. Some of the rooms have bulky antiques; a few of these are Greek, but it is difficult to guess what innovations the Greek Archaeological Service has introduced since the Dodecanese became part of Greece in 1947. The poetry of time here is nowhere to be read.

Beaufort and Krak des Chevaliers, Crusader castles in the Levant, and at least one in Cyprus from which the Hospitallers, the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, had been ousted, are beautiful anomalies which provide two of the four stages of the knightly apocalypse. Rhodes is third, but seems too much of the West to stir nostalgia….

Oh, yes the editor! The entrance on the side street below the vertical newspaper sign is piled with rubbish, including dusty piles of old issues. The stairs are cluttered, too, and on the third landing, a relatively clean passageway leads to a locked double door. A machine clatters loudly behind the door. But no one answers.

It is early evening still, and, nearby, an old part of town dog-leg, sometimes unpaved streets make up the Turkish quarter. The mosques are closed and will be restored. Rhodes has more Turkish remains than any other part of Greece; there is even a library with Islamic volumes. Because of the late Greek takeover after World War II, the Rhodian Turks post-dated the wholesale exchange of populations in the 20s and their buildings persisted with them. On a square overlooked by the Sultan Mustafa Mosque the beautifully-domed Turkish hammam, now rebuilt, again functions as a municipal bath-house.

The Archaeological Museum in the former Hospital of the Knights is an unassuming two-storey square building. Beyond the racks of postcards and booklets the great courtyard is still gracefully shadowed in the early light. Statuary stands about informally and piles of stone cannon and catapult balls give geometric accents.

In the classical section, first the heads of Helios, Menander and a Hellenistic Dionysos, and other incomplete pieces mainly from the Roman period are scattered around. Several Aphrodites droop on their pedestals, including the celebrated Marine Venus, or Venus Pudica, of the 3rd century BC. The funerary steles of the 5th and 6th centuries BC are more affecting than the later statuary. Opposite, a portico gives onto rooms of pottery recovered from Kamiros and lalysos, making vivid the tactile life of those two resilient cities. Then come Minoan pottery and Mycenaean jewellery to recall early settlements on the island.

The large Infirmary Hall somewhat quiets a sense of unease about the whole of Gothic Rhodes. Treatment wards once filled the great room as well as the smaller ones on the portico, and when there were many wounded, the courtyard portico below also became a series of wards.

The memorial chivalric steles of white marble were taken from the church of St. John which was later destroyed in 1856 when lightning struck it, igniting forgotten gunpowder stores in the cellars. The graceful carving, in low relief is restrained and minimum use is made of ornate forms like leaves. The steles are noble in effect but stop short of ostentation, thus suggesting the monastic aspect of the Order. Names on the memorials convey the international composition of the fanatical corps: Nicholas de Montmirel (commandant of the Hospital), Tomaso Provena, Thomas Newport, Fernando de Heredia. A sarcophagus of classical antiquity which dominates one end of the great hall became in 1355 the tomb of Grand Master Pierre de Corneillan. The lid is in the Cluny Museum in Paris; here there is only a copy.

A second attempt to find the editor ‘who knows everyone’ is successful. A freight elevator leads to the floor of cacophony where now the door is unlocked. In the front office a tanned young man at a cluttered desk readily admits to being Editor Sachariadis. Alert and smiling, he understands immediately what is needed.

“Paul Pavlidis knows all the Americans. He knows everybody. He’ll be at his night club, the Hi-Way Disco, this evening. All the taxi drivers know the Hi-Way.”

The taxi ride takes 12 minutes. At an ill-ordered intersection on the coastal road, in a district obviously developed only recently, a brilliant neon display announces the Hi-Way; it lies at the top of an imposing flight of wide steps giving on a surrounding terrace. A tuxedo-clad host worthy of Manhattan’s Upper East Side and several likewise attired attendants, usher the guest through flashing glass doors, over carpeted steps, around a dance floor, and up the rear stairs to a rather plain office. Pavlidis is personable, talkative, and informative. He has had a full life and wants to reveal it.

The Disco King of Rhodes describes his rise from a beauty parlor operative in Rhodes to an entrepreneur with three discos and several apartment houses. Arriving in Warren, Ohio, in 1962 he attended a state university for a while and then established a chain of beauty shops. By his undoubted talent, he reached a six-figure gross with his komotiria and then opened a restaurant. He married a Greek-American and they produced three children. His American citizenship dates from 1964. The period 1966-72 marks his successful ventures in the stock market.

A joiner and organizer, Pavlidis was for many years an officer in both AHEPA and in the Pan-Rhodian Association, being for five years a supreme vice-president in the latter. He participated as an officer in Greek church and school affairs and in 1966, more adventurously, founded the Hellenic Stars soccer team. His brother Polyvios, still in Ohio as proprietor of a large laundry business, is now president of the Pan-Rhodian organization.

With such a seemingly prosperous and useful life in the New World why has Paul Pavlidis returned to his home island? As he tells the story, the reason would seem to be a largely economic one. After a period of testing the profit potentials of Rhodes, he decided in 1972 after ten years in the States, to sell his holdings and plow his considerable assets into Rhodian soil. It was just becoming obvious that the island was becoming a sea-and-sun resort alternative to Spain and Italy. He built a second apartment house and in 1980 he opened the first of three discos. ‘Inferno’ was its initial name but it now operates successfully as ‘John Player Special’.

The second disco, now his leader, is the Hi-Way, opened three years ago, this time in his first partnership arrangement. Its polyglot staff numbers seventy-five. The third disco, starting in 1985, is named “New York”. The disco season is relatively long in such a sunny isle – from the 25th of March till the end of October. Two of his discos close for the winter but Hi-Way continues through the winter on Friday and Saturday evenings, indicating a perceptible appeal to Rhodian people.

Mr Pavlidis interrupts his biography to announce that the light-show is about to begin. He leads down suspended stairs to a domed circular arena then through flashing lights to a banquette below a rampart-like bar where bartenders mix drinks, and brings attention to an overhead structure of hinged black metal beams and braces. Deafening symphonic music pours out of the speakers Pavlidis has imported from Germany. Then the great contrivance above begins to open, colored light and strobes play about the whole complex, and perfumed smoke pours from a dozen vents. The ceiling unfolds like the space station it has been designed to suggest, recalling all of the blockbuster Encounter films of the past decade. Yawning wider, revealing more floodlights, Richard Strauss, Rimski-Korsakov and finally Beethoven issue from the magnificent audio system.

After ten minutes or so, when the overhead monster has refolded its tentacles, and the music has modulated into disco, once again the Disco King of Rhodes can be heard. Now, he is extolling the marvellous climate of Rhodes, one of the factors that led to his return. He goes on with a resume of the omoyeneis. Among the 3000 or so American citizens living in Rhodes are a few purely Yankee retirees who find the island pleasanter and less expensive that the US. Returned Greek friends of his have invested in business like rent-a-car, bus service, and apartment houses. But, quite a few of the omoyeneis, estimated at about 25 percent, eventually return to live in their adopted land. Teenage children are apt to find Rhodes uninteresting in spite of the California-like climate (330 days of sunshine) and the marvellous swimming. Many older people miss the comforts that ancestral villages do not offer. They hate waiting in lines at government bureaus and the sometimes arbitrary money controls dismay them. They get angry at the red tape snarling a simple matter like getting a driver’s license.

Did he feel any prejudice from the Rhodians who haven’t been abroad? None! One surmise the omoyeneis is an accepted Rhodian tradition. Are they selling their birthrights? one wonders, thinking of the sand, the sun, the serrated shores, the edifices of vanished cultures’. And one concludes, No, they are just renting them out. But those hotels crowding around exquisite bays are of permanent concrete, stronger than the walls and bastions of the knights. Who knows? It will be necessary to come back and look again in 500 years.