A very large part of Greece is covered by limestone, which is susceptible to a phenomenon known as karstification, or the development of caves. The reasons for this are mainly chemical. The existing joints in rocks play a significant role as well, acting as channels for water carrying the chemicals, so that they can pass through rocks which would normally be impermeable. The result is that Greece has more than 7500 caves of varying sizes. Data for all these caves are kept in archives accumulated by the Hellenic Speleological Society during the last 40 years.

Many of these caves play a very important role as repositories of geological, biological, and climatic history; they act like the drawers of an archive or a computer hard disk. There are no cards or files, but the caves contain enough sediment in which information about past life, climates, and volcanism are permanently saved. They simply have to be retrieved and decoded by correctly organized pal eontological excavation.

Studies reveal that the available data in island caves is entirely different from that of mainland caves in respect to fauna. Mainland caves in Greece contain sediments that were deposited mostly during the Pleistocene epoch. In the sediments are numerous fossil remains from mammals that once lived in Greece. On the mainland these cave fossils include continental species that usually are identical to those found all over Europe in sediments of this epoch. This is not the case with island cave deposits, however.

In these caves fossils from the unique ‘endemic island’, species are preserved. The expression ‘endemic island’ species is used for those that differ significantly from their mainland relatives and ancestors. For the evolution of an endemic species from its parent mainland species there must be a population isolated geographically and genetically for a long time.

In studying endemics, scientists have to answer questions, many of which still have no answers, despite the amount of work which has been done on them. The most important are those dealing with migration routes and their dates, ancestor species, the duration of isolation, the environmental factors which influenced the evolutionary paths, the causes of extinction, and the general composition of fauna.

For every island we must answer the question: was its fauna balanced; that is, similar to mainland fauna, or unbalanced, i.e. dissimilar, and thus endemic? In answering these questions, much precious information is gathered. For example it is now well known that endemic island species on Greek islands include dwarf elephants, dwarf hippos and deer and micromammal species larger than their mainland relatives. It’s very interesting to note that endemic island fauna always includes one of the three above mentioned animals also found on Indonesian islands, and in the Japanese Archipelago.

Large carnivores, although they were always present on the nearby mainland, have not been found on is-lands as endemic species. These facts, here very simply presented, give the were always present on the nearby mainland, have not been found on islands as endemic species. These facts, here very simply presented, give the mice for instance – can migrate easily on drifting tree trunks and other floating debris. So science had to answer the question: How narrow were these sea corridors, given that they could be crossed by some mammals that can swim? To answer this question we have to use some data about climates of the distant past and their role in sea level changes. It is now very well known that during the Pleistocene epoch the earth experienced very strong climatic changes. When the climate was extremely cold, enormous quantities of water were bound in ice sheets covering high mountains, and plains at high altitudes. The sea level dropped to very low levels: up to 120-140 metres lower than the present level. While this was happening, some islands became extensions of the mainland, the area of others increased, and sea corridors between islands and mainland became much narrower. At such times new small islands emerged in these sea corridors. When sea corridors were narrow, mammals capable of swimming had greater opportunities to reach a nearby island, sometimes using the islands in between as stepping stones. But even in such cases there was no isolation when the mammals could easily return to the mainland or cross the corridor in either direction. Isolation could only occur when the existing sea corridor had become very difficult to traverse.

Conversely, the result of a warm climate is the melting of polar ice sheets, which greatly raises the sea level. (Sea levels about 28 metres higher than today are very well documented in numerous localities in Greece and in other countries.) At such warm times, sea corridors became much wider, the area of each island decreased and also parts of the nearby mainland were covered by the sea. The sharp decrease in area on some islands was probably a very strong factor leading to enormous environmental pressure and possibly in some cases to the total extinction of some isolated endemic animals.

It is also very well known that in the Aegean Sea there are numerous volcanic centers (Aegina, Poros, Methana, Santorini, Nisyros, etc.). Some of them are still active or in the process of dying today. When there were great eruptions, areas of land were covered with thick layers of volcanic ash, destroying grasses, sometimes trees, and causing the pollution of drinking waters. It is obvious no elephant, hippo or deer could survive such a disaster, especially if it could not migrate again, to unaffected areas. It has still to be clarified whether volcanism or other environmental factors force some mammals to leave their mainland home and migrate to a nearby island, or if they just simply try to migrate to new places.

Having in mind these ideas about palaeoclimatic changes (without the bad influence of man!), migration routes, volcanism, etc., the facts as they are presented to us in numerous localities on many Aegean islands are more understandable. On Crete alone more than sixty localities with endemic

mammals have been discovered. This number increases every year.

The collection of fossils of island endemics started long ago. Some important collections and publications were made during the first decade of our century by Miss Dorothea Bate who, dressed as a man, made explorations on the islands of Crete and Cyprus. Isolated specimens have also been found on other Aegean islands. Outside of Greece, dwarf mammals lived on the islands of Malta and Sicily, where the remains of the smallest elephants ever to have lived on earth have been been found.

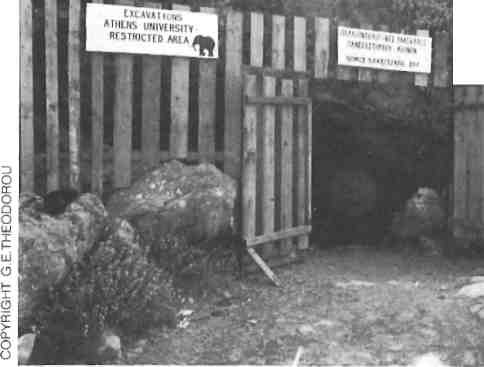

In November 1971, Dr. Nikolaos Symeonidis, Professor of Paleontology and Geology at Athens University, vi-sited the island of Tilos to study some human remains embedded in the very hard sandstone at Aghios Antonis Bay. He went there to follow up information given to him by his friend, Dr. Pantelis Kammas. The human remains in the sandstone proved to be whole skeletons that had been buried on the coastal sands in historical times. They were not fossils. Some of the skeletons are still there under the sea. Having plenty of time on his hands while waiting for the next ship, Symeonides visited some of the caves of the island. In one of them trial excavations brought to light after only a few minutes work the first lam-melae from dwarf elephants. The rich, easily worked sediment was very promising. Excavations were started by the Museum of Geology and Paleontology of Athens University and they still continue, depending on available financing, often with the collaboration of the Museum of Natural History in Vienna. Charkadio Cave has proved to be the richest dwarf elephant locality in the world. The excavations, eight to nine metres deep in the rich sediment, partly of volcanic origin, here brought .to light more than 12,000 bones belonging to more than 38 elephants; males, females, very young, and geriatric specimens. The first studies allowed the working group to put these dwarf elephants in two taxa, one including very small elephants and one slightly bigger dwarf elephants. The results of the first excavations, carried out in a restricted area of the cave, gave the impression that the smaller elephants lay higher in the sediment bed and the bigger ones lower, indicating that the smaller ones were chronologically later: and the bigger ones earlier. The biometrica! and morphological study of the material that has been collected up to 1982, carried out by the author of this article, indicated that there were really two size groups of elephants and their heght varied from about 120 to 150 centimetres. (The results of the later excavations showed also that bones of the bigger dwarf elephants were collected also at the higher and later sediments.) It is also known that in the recent elephants, sexual dimorphism occurs, females being smaller than the males. Normally every mammal population is expected to have equal numbers of males and females, a fact which was borne out by the numbers of each sex on Tilos. For the present we accept that they belong to Paiaeoloxodon antiquus falconeri BUSK.

This name is very provisional. It needs to be changed; but we must wait for some more information about the skulls and the vertebral columns of the Tilos elephants. This name has been given in the past to other Mediterranean elephants whose evolution was parallel with that of the elephants of Tilos. Until now, because of financial problems, only 20 percent of the sediment of the first chamber of the cave has been excavated. There is still at least one side chamber untouched, and possibly more to be found as the sediment is slowly removed. Elephant bones have been collected to a depth of about four, metres.

Absolute datings show that they lived on Tilos from about 50,000 years ago down to 2000 -1,500 BC. It is unknown how long they lived on the island before they entered the cave. In the sediment beneath the elephant bones there is a layer from which deer bones have been collected. Absolute dating for the deer is given at about 140,000 years ago. We must note here that roughly at this time large amounts of volcanic tuffs were deposited, which came from the nearby island of Nisyros where there is a large crater today. Clearly it became impossible for the deer to survive on Tilos while layers many metres thick of volcanic ash accumulated. This also explains the fact that the deer of Tilos are only very slightly endemic, because they became extinct before they had time to evolve to endemic forms. When the deer lived on Tilos the island area was far greater than it is today because the sea level at that time was very low.

Since, however, the layers beneath the deer remains correspond to a period when Tilos was very small due to a high sea level, it seems unlikely that we will find other mammals dating from this period. Future work will clear up these questions for which data are missing at the moment.

At the time of the arrival of the elephants on the island, Tilos was much bigger than today, and its area was possibly increasing; we know that it reached its maximum size around 18,000 years ago. At this time Tilos and all the other Aegean islands were closer than ever to the mainland, and to the first appearance of man. It will be some time before we know when man came to each island, and what effect he had on its fauna. It seems possible that man met the Tilos elephants eye to eye since we find some strange pieces of tusk that may have been fashioned by primitive man to be used as tools.

Drillings on the Eastern Mediterranean sea floor and sedimentological studies in the sediments of the Charkadio Cave show that volcanoes all over the Mediterranean were spewing their ash at different times. Experts have established the presence off the coast of Rhodes of volcanic ash from Ischia in the Bay of Naples corresponding in time with the big eruption about 23,000 years ago. Santorini erupted at different times while elephants were still living on Tilos. Exact information is still lacking, but the influence of volcanic activity on Santorini was never crucial to the Tilos elephants with the possible exception of the great eruption of about 1.500 BC. The exact causes for the extinction of the elephants on Tilos are not yet clear. We do not know yet what triggered the process and what was the final blow. Nature, with the help of Santorini? The shrinking of Tilos in size because of the gradual warming of the earth and the change in sea level? Or Man?

Man long ago noted the existence of fossil bones in caves all along the coasts of Crete, Cyprus, Malta, and Sicily. The skulls of the dwarf elephants with their large nasal openings for the proboscis, may have been the origin of the myth of the Cyclops. This aperture was thought to represent the great eye of Polyphemus, whom Odysseus blinded.

The key to the mystery of the elephants’ extinction is possibly hidden in the Charkadio Cave sediments, or in one of the many other caves where fossils are found. We must not forget that Greece has thousands of caves, and many of them are still entirely unexplored. Unfortunately, some of the fossil records in caves have been destroyed by people with no background in geology, vertebrate paleontology or stratigraphy. In such cases, they have done nothing more than erase much of the available information. This is a tragedy for science, because any information, if not correctly decoded, is lost forever.

Further reading

SONDAAR, P.Y., G.J. BOEKSCHOTEN, Quaternary mammals in South Aegean Island arc with note on other fossil mammals from the coastal regions of the Mediterranean, I/II Proc. Kon., Ned., Akad., Wetensch. B. 7:556-576. Amsterdam, 1967. Cum. lit

SYMEONIDIS, N. Die Entdeckung von Zwergelefanten in der Hohle “Charkadio” auf der Insel Tilos (Dode-kanes, Griechenland). Ann. Geoi. Pays Hell. 24:445-461, Athens, 1972.

SYMEONIDIS, Ν., Fr. BACH-MAYER, H. ZAPFE. Grabungen in der Zwegelefanten Hohle Charkadio auf der insel Tilos (Dodekanes, Griechenland). Ann Naturh. Mus. Wien, 77:133-139, Wien,1973

THEODOROU,G. Pleistocene elephants from Crete (Greece).

Modern Geology 10:235-242, United Kingdom, 1985.

THEODOROU, G.,Enviromental factors affecting the evolution of island endemics: The Tilos example from Greece.

Modern Geology 13:183-188, United Kingdom, 1988.

Dr. George E. Theodorou is Lecturer at the Department of Historical Geology and Paleontology, Athens University.