Our knowledge of what the music of the ancient Greeks actually sounded like remains largely conjectural, despite many inspired attempts to recreate it. We are left with no equivalent of modern sheet music; indeed, musicians almost certainly played completely by ear, just as the words of songs were learnt by heart. What we do know, however, is that music played a very important role in ancient Greek life, a role that was not restricted to the field of entertainment as it tends to be nowadays. From being primarily an accompaniment to the recitation of epic poetry or to dance in Homeric times, music became a major art form in its own right by the fifth and fourth centuries BC, and as one of the arts of the Muses (mousike) it formed an essential part of a well-rounded education. Plato recommended that education should be split into two basic disciplines: ‘gymnastic’ for the body and mousike for the soul.

Like all ancient peoples, the early Greeks also attached a magical significance to music. Musicians and singers were thought to be inspired by the gods. In the Odyssey, the minstrel Phemius pleads with Odysseus for his life on the grounds that he is “… a singer, one who sings for gods and men” and that “… a god has breathed all kinds of melodies into my mind.” Music could change emotions and thoughts and hypnotize unsuspecting mortals into behaving strangely and irrationally. In so doing, the Sirens lured sailors to their doom with their enchanting voices.

The Furies and the Sphynx also practiced magical singing. Special magical tunes could cure grief or even illness. Plutarch tells of Thalitas, a Cretan musician who succeeded in ridding Sparta of plague by his religious songs. Musical instruments themselves were divine gifts; the invention of each attributed to varying deities by the sometimes conflicting myths.

One of the most surprising things about ancient Greek musical instruments is the sheer number of different names that existed. There are references to at least 23 different string instruments alone, details about which are often sparse. It seems probable, however, that, with typical ancient Greek attention to detail, separate names were given to denote the slightest variation between instruments, perhaps in the number of strings, the materials used or the place of origin.

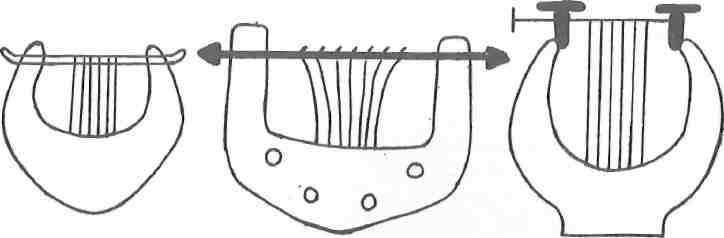

There were three groups of musical instruments: strings, wind and percussion. The first group, the string instruments, belonged mainly to the domain of ‘serious’ art music, and comprised five basic types: the phormynx, the lyra, the barbitos, the kithara and the harp. In Homer’s time, the predominant instrument was what he usually refers to as the phormynx (although the same instrument is variously called a lyra and a kithara). This was a simple wooden instrument, usually with four gut strings (it is sometimes depicted in vase paintings with two, three, five or six, but this may have been due to the ignorance of the artist), with an upright sickle-shaped sound-box.

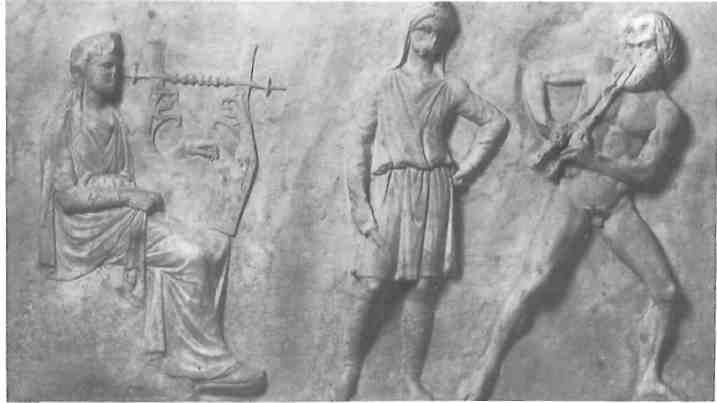

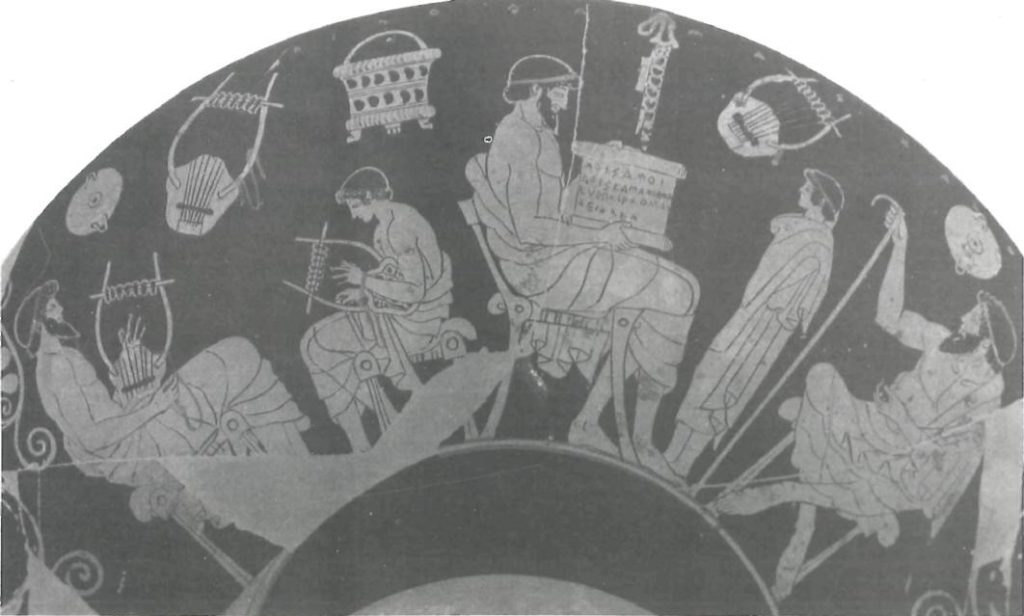

The same basic shape of instrument survives in the ‘cradle’ kithara of classical times. In common with the lyra, kithara and barbitos, two arms rose from either side of the sound box, and were linked by a cross-bar, to which the strings were attached with strips of raw leather. The strings of the phormynx were of equal length, different pitch being achieved by different thickness and tension (like the modern guitar), and were tuned to fourths, fifths or octaves. The instrument (phormynx, lyra, kithara or barbitos) could be played in a standing or seated position, and was held at a right angle to the left side of the body, often supported by a cloth band tied around the wrist. The strings were struck with a large metal plectrum, held in the right hand, while the fingers of the left hand were sometimes used to pluck melodies or damp the strings.

In Homeric and Archaic times, the function of instrumental music was almost entirely restricted to the accompaniment of the human voice. Professional minstrels, accompanying their own recitations of epic poetry, were the staple form of after-dinner court entertainment. Music also accompanied dancing, but instrumental music was yet to develop.

The best known of ancient Greek string instruments is probably the lyra (not to be confused with the modern Cretan lyra, with which it shares few features other than the name!). It is almost certainly of Greek origin, as there is no evidence of its existence in any other ancient civilizations, the earliest lyra-type instruments appearing in Minoan paintings of 1500 BC.

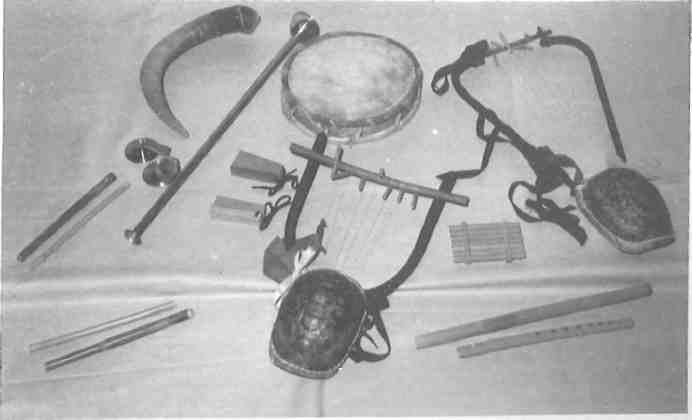

The lyra differed from the phormynx in that the sound-box and arms formed two distinct parts. The sound-box was usually made from a tortoiseshell, or from boxwood carved to resemble a tortoiseshell (hence the lyra was also sometimes known as ‘helis’ or ‘heloni’). Ox hide was stretched over the shell to close up the holes from where the tortoise’s head and legs had protruded. The arms were usually made of wood, but sometimes of goat or antelope horn. The strings (normally seven in number, sometimes more) were made from flax at first and sheep or ox gut later, and were tied and/or glued to the cross bar. This must have made tuning rather difficult.

The lyra was easier to learn than the more complex kithara and was predominantly an instrument for amateurs used in private entertainment rather than public performance. It was Apollo’s favorite instrument and his symbol, but was generally considered to be the invention of Hermes. The Homeric hymn to Hermes tells of how, on the very day of his birth, when the young god found a tortoise, “… he up-ended it, and with a grey iron chisel he scraped out the life of the mountain tortoise… He cut stalks of reed to measure and fixed them, fastening them by ends through the tortoiseshell. Then he stretched ox hide over it by his skill, and added arms, with a cross bar fixed across the two of them; and he stretched seven harmonious strings of sheep gut.”

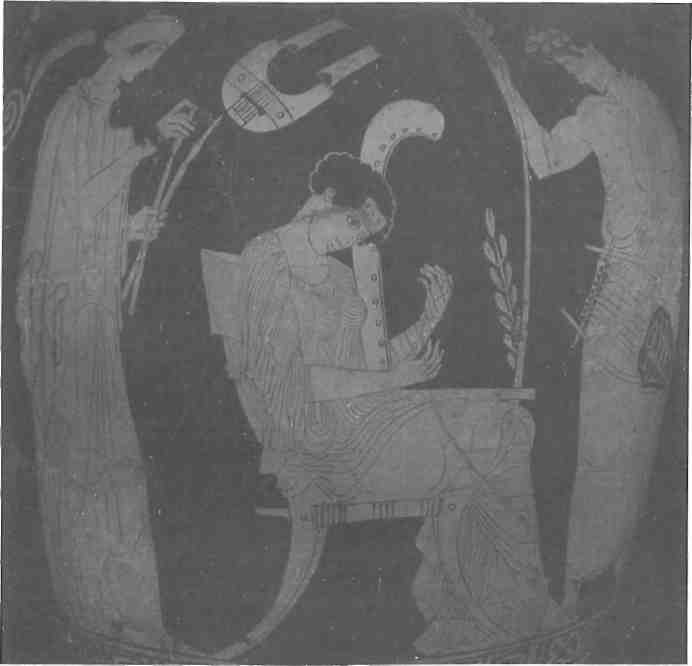

On the same day, however, the infant god made the mistake of stealing Apollo’s cattle, thus, understandably, throwing Apollo into a fit of rage. But when Hermes began to play the lyra, Apollo’s anger was soon assuaged and he accepted the lyra as a peace offering, Similar in shape to the lyra, but more elongated and with a much deeper pitch, was the barbitos. This was the long-armed instrument which appears frequently in vase paintings played by the horse-tailed pointed-eared satyrs. Indeed, it was generally associated with Bacchic revelries, although it was also used by poets. Like the lyra, it had seven strings. Its invention was attributed to Terpander, the great seventh-century musician.

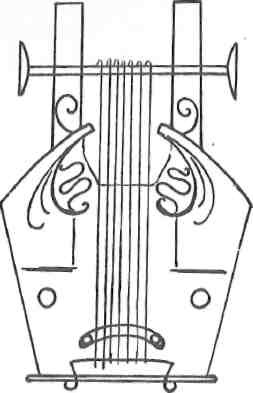

After the first decades of the seventh century, the primitive four-stringed phormynx began to be replaced as the main instrument of public performance by the bigger, fuller sounding kithara. Like the phormynx, it consisted of a large wooden sound-box from which the arms seemed to flow as if the instrument were just one piece. The arms, however, were often intricately decorated, the base of the instrument was flat rather than curved, and it normally had seven strings. Concert kitharas might be up to one metre in height. Along with the lyra, the kithara was one of Apollo’s instruments. He was considered its inventor and was supposed to have taught Orpheus the ‘art’, which is what music had become by the fifth century. Great pieces were composed especially for the solo performance of the kithara.

The ‘cradle’ (aioriki) kithara was the most common of numerous variations on the standard concert kithara. It had a rounded bottom, and the sound box often appears with characteristic ‘eye’ shapes in it, probably sound holes. Unlike the concert kithara, it was played by women as well as men (it is often depicted in the hands of the Muses) and its use seems to have been more amateur than professional. It too had seven strings, sometimes eight. Towards the end of the fifth century more strings began to be added to instruments of the kithara type – something that was frowned upon by purists.

The harp is one of the oldest instruments. The two most ancient renderings of musical instruments in ancient Greek art are in fact a pair of Cycladic marble figures, one holding a harp, another playing a flute. They date from the end of the third millennium and both can be seen today in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Yet in classical times the many different types of harp tended to be considered as foreign. It appears frequently in fifth century vase paintings, nearly always played by a woman (often one of the Muses) in a seated position, resting the harp against her shoulder. It was plucked with the fingers of both hands rather than with a plectrum.

The only wind instrument used in ‘serious’ music throughout the Middle East and Mediterranean in ancient times was a wooden double-reeded instrument, similar in principle to the modern oboe: the ‘pipe’ of the Bible, the Roman ‘tibia’ or the ancient Greek ‘avlos’. The Greeks traditionally traced the origin of the standard avlos to Phrygia in Asia Minor, but there were also several other types of the instrument distinguished by their place of origin -places which had trade ties with Greece such as Libya and Etruria.

Mentioned as a Trojan instrument once or twice in Homer and comparatively rare in Geometric art, the avlos became established in Greece in the seventh century. It was usually made of wood, but also of reed, bone, horn, ivory, metal, pottery or a mixture of more than one material, and comprised two (or sometimes three) short bulbous sections at the top, into which the reed was inserted, and a longer main pipe. The finger holes were usually in the side rather than on the top. The earliest types had four holes, one for each finger, but later in the fifth and fourth centuries a series of metal rings which could be rotated by finger movement to open and close the holes (as on modern woodwind instruments) made the use of up to seven holes possible. According to Aristotle, it was possible to obtain 24 notes with such a system.

These wind instruments were almost always played in pairs, the two mouthpieces resting side by side in the aulete’s mouth, but it is not certain what function the two pipes performed. It seems unlikely that the same tune was played on both, but the idea that one of them was used to produce a ‘drone’ is never actually referred to in its descriptions. Air was probably taken in through the nose. They must have required a lot of muscular effort to blow: vase paintings show auletes with very puffed out cheeks. To support their muscles, some players wore a strap called a ‘phorbia’ tied around their heads. The best reeds (made from the same kind of reed used today by woodwind players) were said to come from Lake Copais, since drained, near Thebes, and reed-making was a specialized craft. Reeds were kept in a small box which hung from the avlos case.

The avloi were in evidence in every sphere of Greek culture: in solo performance, leading the chorus, in competitions, athletic events, dinner party entertainment (an auletris, or flute-girl, who danced as she played, was a common feature at symposia), and in connection with Dionysian dancing and worship. Its peculiarly plaintive sound was said to have a powerful effect on the emotions, and was considered especially suitable to accompany drama. However, conservatives like Plato considered only ‘really Greek’ string instruments to be in their class and disapproved of the avlos.

Different stories attribute the invention of the avlos variously to Hermes, Athena, Apollo and others, but the most colorful tale tells how Athena picked up a piece of bone on Olympus and blew into it to imitate the wailing and whining of the snakes which grew like hair on the heads of the Gorgons, Stheno and Euryale, as they lamented the death of their mortal sister Medusa. But Hera and Aphrodite made fun of Athena’s puffed out cheeks, and when she saw from her reflection in a stream that her face did indeed become distorted when she blew into it, she flung the pipe away, casting a curse on whoever might pick it up.

Not taking the curse seriously, the satyr Marsyas retrieved the avlos and taught himself how to play so skillfully that he challenged Apollo, on his lyra, to a music contest. Apollo grew so livid at this insolence that he skinned the unfortunate satyr alive.

Apart from the avlos, the ancient Greeks had two other wind instruments: the ‘salpinx’, a kind of bronze bugle with a bone mouth-piece, used to give military commands and signals at athletics meetings, and the ‘syrinx’, or so-called ‘Pan-pipes’. The use of the latter was strictly pastoral and played no part in serious ‘art’ music. Shepherds played it both to call their flocks and for pleasure.

The original Greek instrument was composed of seven (or sometimes five or nine) reed pipes of equal length, fixed together with wax (or sometimes with metal bars or flax) to form a rectangular shape. (It was a later version, common in Roman times, that was shaped like a bird’s wing and had as many as 15 pipes.) Different pitches were attained by filling up in varying proportions the lower part of each pipe with wax, and sound was produced by blowing across the top of the pipes. Fonall its simplicity it must have had a hauntingly sweet sound. Euripides refers to the “sound of the melodic syrinx” and Electra is addressed by the chorus as “breath of the gentle syrinx”. A Homeric poem to Pan says “… not even the bird singing the sweetest song in the leaves in spring could produce such a tone.” The most picturesque myth surrounding the instrument tells how Syrinx, once a nymph in Arcadia, ran away to escape the amorous advances of the goat-god Pan. When she reached the River Ladon, exhausted by her running, she begged the river to save her. Her plea was answered, for when Pan stretched out his hand to seize her, she turned into a reed. Pan soon got over his initial disappointment when he heard the magical sound of the wind blowing through the reeds. He picked a few and joined them together with wax to make the syrinx, which became his symbol – he very rarely appears without it in vase paintings.

A later invention, based on the same principle as the syrinx and the forerunner of the modern organ, was the Alexandrian ‘hydraulis’ or water-organ in which a flow of air was produced by hydraulic pressure. The air entered a series of pipes from a separate box while a system of slides was operated from a keyboard, releasing the air into whichever pipe was required. By this time, bellows-type organs operated by foot pump were also widespread in the Mediterranean and Middle East.

The main role of instruments belonging to the third category – percussion -was to accompany dancing of all types – public, private, and the orgiastic dancing of the cults of Cybele and Dionysus. Those most commonly depicted in anci¬ent art are ‘krotala’, or rattling instruments, in the form of large castanets made of metal, wood, shell or pottery, held in the hands of dancers. Small metal hand-held ‘kymbala’ (cymbals) and a hand-drum called a ‘tympanon’, made from animal skin stretched over a rim, were also used. Like the avlos, however, percussion instruments were not considered to be in the same class as the classical kithara, and some auth¬ors link them to a coarse and unseemly type of music.

Music, then, accompanied the ancient Greeks in every sphere of life – at work and at play. But just as today we would not expect to hear an electric guitar in church, or a bouzouki in a disco, the role of each instrument was strictly defined.

Many of the ancient Greek instruments bear a close resemblance to those of other ancient cultures in as disparate places as South America, Japan and Egypt. None of them, however, were to survive in an unaltered form into post-Byzantine Greece.