A few weeks ago, I was amazed to find Russian goods on sale at my local street market. Smiling Greek-speaking ladies were selling tea-towels, tea-towel fabric, little metal toy cars representing Russian taxis, ambulances and so on, tea pots, tea cups, samovars and babushka dolls.

“But where are you from?” I asked them.

“From Kazakhstan.”

“For heavens sake! what were you doing in Kazakhstan?”

They were Pontians, they explained to me, Greeks from the Pontos, on the shores of the Black Sea, in Asia Minor. I remembered that I had read about them in the local papers recently. With the relaxation of travel restrictions in Russia, brought about by perestroika, many Greeks from the Pontos were returning to the mother country they had never seen.

Who are these Greeks and how did they end up so far away? I thought the history of greater Greece, the story of the lost hopes and aspirations of the outlying Greeks of the Balkans and Asia Minor had come to an end in 1922. And yet here, suddenly, were hundreds of thousands of people, longing to return.

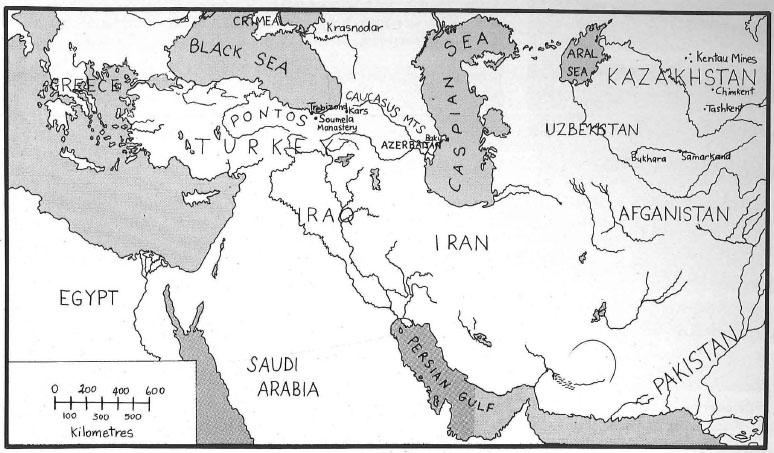

To compress two millennia into a few words, Greeks entered the Black Sea as early as Jason and his Argonauts. They established colonies all around the coast of the sea they named the Euxinos Pontos. Some of the most famous of the colonies were offshoots of the Ionian city of Miletus, such as Sinope, founder in its turn of Kotyora (today Ordou), Kerasounta and Trebizond. These are the cities Xenophon described in 400 BC, when his Ten Thousand, descending from the Pontic Alps, had their famous view of the sea.

Here they ate the intoxicating honey, made from the flowers of the Pontic azalea. The Pontian Greeks of the area called this honey ‘παλαλόν μέλ’ or “crazy honey” until their uprooting and dispersal in 1922, and they insisted that if one ate it raw, one would get drunk.

These cities formed the kingdom of the Pontos, founded by two Persian satraps, which endured until conquered by the Romans in 63 BC. With his Greek wife and mother, the last king, Mithridates the Great (120-63 BC), endeavored to unite the Persian and Greek cultural elements into one whole, much as Alexander the Great had attempted. The Roman conquest brought periods of great prosperity when trade routes opened from the interior of Asia to Trebizond.

Eventually Christianity came, and the famous monasteries were built, enduring from earliest Byzantine times to the 20th century. Symbol of this endurance is the monastery of Panaghia Soumela, founded early in the Byzantine period on Mount Mela, near Trebizond, between the fourth and ninth centuries AD. According to tradition the Athenian monks Barnabas and Sophronios brought with them at the time an icon of the Virgin, painted by Saint Luke, which had been in the great cathedral of the Virgin Mother of God; that is, the Parthenon.

Not only the Byzantine emperors honored this great monastery, but later many sultans also granted it firmans and chrysobulls, confirming the benefits given to it by the Emperors of Trebizond. The Empire of the Great Com-nenes fell to the Turks in 1461. In the nearly four hundred years that followed, there were many periods of despair, when the Greeks of the Pontos fled, for example to Russia and Moldovlachia, or converted to Islam to escape persecution.

Some became ‘cryptochristians’; secret, hidden Christians, who professed the Moslem faith, but kept speaking Greek and secretly continued to practice their Orthodox faith in underground churches with priests disguised as dervishes or hodjas. Amazingly, these secret populations of Christians only came to light in 1856 after perhaps two hundred years of concealed worship. This was when the Sultan Mejid was forced by Russia and the other Great Powers to sign a Reform Decree promising freedom of religion, the right to repair churches and build schools, and so on.

Altogether some 20,000 secret Christians came out of hiding after 1856. It is believed that many in outlying areas were afraid to reveal themselves, and some Pontic organizations hint that even today there may be some groups of secret Christians in the Pontos. In fact one famous cryptochristian from Trebizond was also responsible, at least in part, for saving the Greeks from massacre in 1821, following the sultan’s orders to that effect after the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence. This may have been Osman Pasha Satirzade of Trebizond, possibly a descendant of the Eyoublides, an islamicized Greek family, who also intervened to save the Greek populations during the Russo-Turkish War of 1828. Many Pontians were obliged to flee into Russia as a result of that war. After all, Russia was a friendly Orthodox Christian power located right next door; moreover, as a result of the hostilities, the Turkish authorities looked on the Greek Orthodox populations with suspicion, considering them to be pro-Russian. Matters worsened with the Russo-Turkish conflicts of the 1870s. With the victory of Russia over Turkey in 1877-1878, Russia acquired the district of Kars, forming it into the Karskoyie Oblast. Many Pontians then left their villages and emigrated to Kars, founding about 74 Greek villages in the area. Greeks were scattered all over the Caucasus, and some sources give the number of about 150,000 for the Greek Pontians of the Caucasus at the beginning of the 20th century.

After the 1850s there was a period of prosperity when the Greeks of the Ottoman Empire hoped that some beneficial compromise might improve and stabilize their position in the empire. Some even looked towards a greater Greece, a resurgent Byzantine Empire, or, perhaps more reasonably, a reformed Ottoman Empire in which they would be able to retain their positions of importance in finance and commerce and the administration, but as equal citizens.

Many buildings of this period in the Pontos as well as all over the empire attest to this new-found confidence. One example is the ‘Frontistirion’ of Trebizond, which as an institution dates at least from 1638. The building one can still see today was designed by the architect Alexandras Kakoulidis and funded by about one hundred- Trebizondians at the end of 19th century. In 1902 it had 730 students, plus another 250 in its annexes. The boys’ and girls’ schools at Sinope were built at the end of the 19th century. Wealthy Greek families built themselves beautiful homes, easily distinguished today by the neoclassical elements used in their design.

As the multi-ethnic Ottoman Empire collapsed, the struggle to create a Turkish national state with its attendant resurgent nationalism, brought about the destruction of those minorities, particularly the Greek and Armenian which had enjoyed economic prosperity in the 19th century. After the military coup of the Young Turks in 1908, the Pontians found themselves liable for obligatory military service in the infamous work battalions, particularly during the Balkan Wars. With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, whole villages were marched inland from the coast, to die en route in the dreadful winter conditions. Russian forces occupied the eastern Pontos and the Greek inhabitants the coast of Western Pontos were slaughtered or fled to the mountains and formed guerilla bands.

The outbreak of the Russian Revolution and the subsequent withdrawal of Russian forces, followed by the Greek catastrophe in Asia Minor in 1921, left the Greeks of the Pontos unprotected. Those who were not killed in massacres of entire villages or in forced death marches of helpless populations (some sources estimate perhaps 200,000 were killed out of a total population of around 700,000 in 1913), were forced to flee. Though those few survivors of the death marches were allowed to return to their homes after the surrender of Turkey in 1918, the exchange of populations decided on by the Lausanne Convention of 1922 sent the remainder as refugees to Greece.

But there were many Pontians who were already in Russian territory, or who were caught behind the Russian lines, or who were forced to flee into Russia to escape and then were not allowed to leave. In 1920 the Turks captured Kars, and through the Treaty of Alexandropol acquired Kars, Van and the district of Mount Ararat.

Today at the monastery of Panaghia Soumela, a center of learning and an inspiration to the surrounding Christians through all the centuries of Turkish rule, are the ruins of an imposing four-storey guest house, built in 1864 to replace an older wooden structure. The last visitor signed the guest book on June 24,1921. The monks remaining at Panaghia Soumela were forced to leave in 1923, fleeing secretly at night, without being allowed to take anything with them. The monastery became the lair of smugglers and bandits, and was burned in 1930 by tomb robbers and antique smugglers.

The treasures in the library were lost, except for the 67 handwritten codices and the 150 books now in the Ankara Museum. However, the three most important treasures of the monastery were saved, hidden by the monks in the nearby metochi of Aghia Varvara before they left. When relations between Greece and Turkey were normalized, in 1930, the holy monk Jeremiah Soumeliotis sent a confidential letter to the Metropolitan of Trebizond, Chrysanthos, telling him where these treasures had been buried.

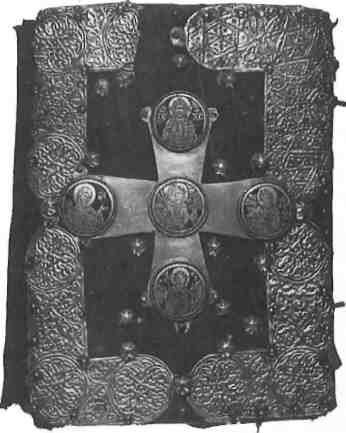

Venizelos heard of this and wrote to Ismet Inonu, then prime minister of Turkey, and obtained permission for the monk Ambrosios Soumeliotis to go to the monastery and bring back the treasures: The famous icon of the Panaghia painted by Saint Luke, the cross given to the monastery by Emperor Manuel III, and the Gospel of Saint Christopher.

Except for its cover, the Gospel had been destroyed by the damp. It was placed, nevertheless, together with the cross and the icon of the Virgin in the Byzantine Museum in Athens. In 1952 the Pontians transferred the icon to the new monastery of Panaghia Soumela which has been built in Macedonia on the slopes of Mount Vermion, between Kozani and Veria. Every year on 15 August, the feast of the Assumption, Pontians gather from all over the world here. The Gospel and the cross, however, remain in the Byzantine Museum today.

A large proportion of the people fleeing Turkey early in this century settled in the Caucasus along the Black Sea coast, which closely resembled their homeland. Trapped there by the revolutions, wars and national disasters of the post-war period, they built homes and prospered as best they might, though the late 1930s saw them suffering the closure of their schools and newspapers. In 1942, Greeks from Krasnodar were sent to Vladivostok and in 1944 Greeks from the Crimea were sent to Siberia and Northern Kazakhstan. Needing to populate the outlying socialist republics in an effort to speed up industrial development and especially the lead and zinc mines in Central Asia, Stalin chose those people who were least able to protest, having no national state of their own within the Soviet Union, and little contact with their own home country that they had never seen.

One night in 1949 all the Greek families of this area of the Caucasus were aroused by the infamous knock on the door and were told that they had half an hour to collect whatever of their possessions they might carry before they had to leave. They were loaded into army vehicles and taken to the train, where they waited for two days for all the people to be gathered from surrounding areas. The journey into Central Asia took 14 days, and they had no idea where they were going or what would happen to them. Some even thought that they might be sent to Greece. In fact, they were taken to the area near Tashkent, in Kazakhstan, an area of desert and steppe, exposed to cold blasts of Siberian air from the northeast. Tashkent had been one of the main cities on the caravan route between China and Europe, and had been designated by the Soviets as the primary manufacturing city of Central Asia.

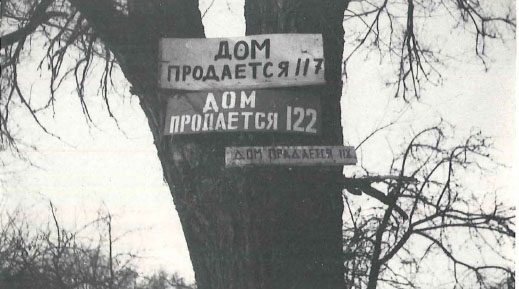

The Greeks were taken off the trains in groups of around 2000 people at small villages and settlements. The Soviets had provided for housing, but it was usually little more than a stable or tent. Some were Finnish prefabricated houses, some humble mudbrick houses built by the local inhabitants. However, the Pontians worked hard and as soon as they could they bought houses from the locals, tearing them down and building new ones more to their liking out of the prevailing loose mudbrick. Some of them were settled near the Kentau group of lead mines. Chimkent, nearby, was considered in the 1950s to have the largest lead smelter in Eurasia.

At first the Pontians were not allowed to leave their villages. They needed a permit to travel even a few kilometers and were guarded by troops as though in jail. But after Stalin’s death in 1953 matters relaxed and after 1960 they were allowed to travel within the USSR. Incidentally, its interesting to note that according to official statistics, 25 percent of the Pontians arriving in Greece at this time are truck drivers by profession. It seems that one needed an internal passport to travel more than seven kilometers from one’s place of residence, whereas truck drivers were free to travel all over the country.

There are Greeks scattered all over Siberia today, and all over Russia. Many of the people from the Kentau area were originally construction workers. They built houses and other structures in the surrounding areas, some of which display recognizably Greek architectural elements, thus preserving the evidence of this remarkable exile.

All this time these people remembered who they were. They remembered they were Greeks, and that they had been trying to reach Greece when they were stopped in the Caucasus. Their most constant thought was how to return. When in 1963-1964 travel restrictions were relaxed, some were able to travel to Greece. With further relaxation of travel restrictions brought about by perestroika, these exiles, perhaps 50,000 in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, have started to return in earnest. And now, of course, the ethnic unrest of recent months in Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, and Tadhzikistan has influenced them to leave as soon as possible, as well as many of the Pontians of the Caucasus.

How many Greeks are there in the Soviet Union today? Official sources estimate between 400-500,000 people. The Russians themselves give a figure of close to one million people of Greek descent, including people who have changed their names and taken Russian citizenship, married Russians and otherwise disappeared in terms of being of Greek origin from official censuses. Perhaps 150,000 people speak Greek as their mother tongue.

Here it is interesting to note that the Greeks of the Pontos spoke various idiomatic forms of Greek referred to as the Pontic dialect, one of the oldest Greek dialects, preserving ancient Ionian forms, relics of the ancient Greek cities of Ionia, and proof of the Pontians links to that ancient past. Though this dialect has largely disappeared amongst those who came to Greece since 1922, the Pontians of the USSR, still as isolated linguistically as they had been amongst the Turks of the Ottoman Empire, have preserved their dialect. Today, the returning Pontians have two language problems: the young people often speak only Russian, and the older ones speak the Pontic dialect rather than modern Greek.

Sources refer to Gabriel Popoff, formerly Papadopoulos, a member of the Soviet parliament and a professor of economics at the University of Moscow, who formed a Pontian Federation and has even touched on the idea of an independent “Greek Republic” in the Soviet Union near Krasnodar where many Pontians live who have returned from central Asia. Needless to say, the Russians are as reluctant to see the Pontians leave as the Greek authorities are eager to welcome them, and for many of the same reasons. Besides being energetic, industrious and patriotic, they also help to leaven the Moslem majority in Central Asia, and can, if they want, help to promote growth in under-developed areas of northern Greece.

The people leaving the Tashkent area have had, until recently at least, to face many attempts to take advantage of their situation. They were allowed to change only a small number of rubles into foreign exchange and in Tashkent in particular they had to face strict limits on the number of household goods they were allowed to take with them. Repatriating Pontians have reported that to clear customs in Tashkent they were only allowed to take a maximum of ten boxes of goods, each measuring no more than lxlxl. 5 metres; they were not allowed to take duplicate electrical appliances and were obliged to pay the customs official in Tashkent in foreign exchange in order to jump the queue or risk having their exit permits expire. Needless to say the housing market has fallen drastically, so these people are once again losing the investment they had made in their homes.

Once on their way, many people traveled by train to Moscow, where they had to wait anxiously, trying to buy tickets for the train down through Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Yugoslavia. This train drew few passenger cars, and tickets commanded vastly inflated prices on the black market.

Others travelled to the Black Sea so as to take ship from Odessa. A few came by car or even flew.

According to official figures, about 6000-6500 Pontians arrived in Greece in 1989, at a rate of about 500 per month. This year the rate of arrival has increased substantially and, by the time shipping gets started on the Black Sea in April, Greece will be receiving around 1200 Pontians per month, with an expected total for 1990 of around 20,000 individuals. The repatriating Pontians, according to official statistics taken from a study of the people who have arrived to date, are truck drivers (25 percent), those engaged in urban services, such as photographers, sales girls, etc (19 percent), craftsmen and artisans (16 percent), students (14 percent), doctors (3 percent), engineers (2 percent), workers (13 percent), nurses (4 percent) and farmers (3 percent – this figure is low because farmers traditionally are the last to abandon their land.)

Arriving at the Greek borders, these people may have consular passports if they had registered themselves in the Greek consular files. Others, who had not done so but had declared themselves to be of Greek origin, return with a kind of ‘homecoming’ visa. Still others are Russian citizens. Once in Greece it takes them about three to six months to get their Greek papers, though now special efforts are being made to facilitate the process for certain groups, such as the truck drivers who get their licenses recognized right away.

Needless to say, these people, arriving suddenly in an essentially foreign country, often not speaking the language, in desperate need of housing and money and unfamiliar with the local situation, have often been taken advantage of by people here as well.

One particular incident that has received attention in the Greek press is the scandal of the red AMO car license plates. Greeks returning as permanent residents of foreign countries have the right to a car without having to pay the burdensome taxes. Thus, the Pontians, getting off the train at Larissa railway station in Athens, for example, arriving after a journey that has lasted more than 60 years including a detour to Central Asia, would be met by unscrupulous individuals who would persuade them to sell this right for minimal sums. The car would be bought in the Pontians name, but would be kept by the new owner, until a year expired, after which the transfer of ownership could be made legally. Thus many Athenians, it is claimed, are parading around in new hugely expensive Mercedes and so on, for which they have paid little more than the rest of us are obliged to pay for our small cars. However, they are presumably exposed by their red AMO numbers!

After some delay in getting organized, which is doubtless due to a lack of realization of the dimensions of this repatriation, a National Bureau for Confronting the Pontian Question was formed in December 1989 at the Foreign Ministry, with the purpose of coordinating all national efforts. This Bureau, in cooperation with other agencies, has prepared a program which has received the approval of the United Nations Refugee Council.

The Program to Deal with the Question of the Arrival and Settlement of the Repatriating Pontians will provide for overnight reception in special Arrival Centers where the repatriating Pontians will receive health care and, helped by Russian language specialists, will be able to get in touch with Pontic organizations, receive internal travel tickets (if they have a specific destination in mind) and then continue to the Hospitality Centers. These Hospitality Centers (Rendi area in Athens, Keratsini in Piraeus, Boyatzoglou military camp in Thessaloniki) will house and feed 500 people for 15-day periods (1000 per month), offering health care, employment information, help in dealing with customs and other bureaucratic formalities, and connection with other organizations. After this fortnight’s stay, they will move on to Reception Centers where they can stay for six months and learn the language, adapt to the new environment, find jobs and so on. These Reception Centers will be located mainly in sparsely settled areas with possibilities for development (around the town of Larissa, Kavalla, as well as the regions of Xanthi, Rhodopi, Evros). But, of course, the finally repatriated Pontians will be free to move wherever they like.

One can only wish them well and marvel at the courage and determination that have brought them home at last.